When director Stephane Gauger prefaced Saigon Electric by requesting that the audience not take it too seriously, I had to wonder what kind of journey I was in for. Turns out, a fairly unpleasant one.

This film foray into Vietnamese breakdancing and hip-hop culture serves as a reminder that:

1) Not every film in a well-reputed international film festival need be a good film;

2) Just because a film is from another country does not mean it does not fall victim to Hollywood pitfalls.

Even while keeping in mind not to take Saigon Electric too seriously, its over-the-top embrace of all things ridiculously cheesy quickly becomes unforgiveable. Such cheesiness can be found in, but is not limited to, the following:

1) Corny, cliche lines that even afternoon soap operas would find too generic to include;

2) Archetypal characters with little to no depth, many of which can, and should probably, be completely omitted;

3) Poor and predictable soundtracking choices, which include minimal ambient electronic tracks set to images of rolling ocean waves and sunshine as well as hip-hop beats rhythmically misaligned with related dance scenes.

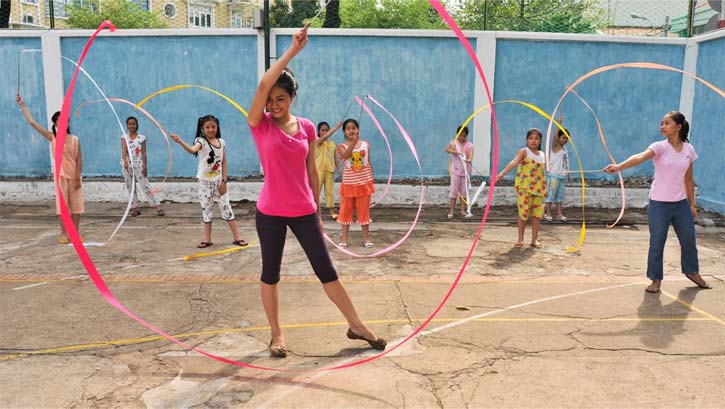

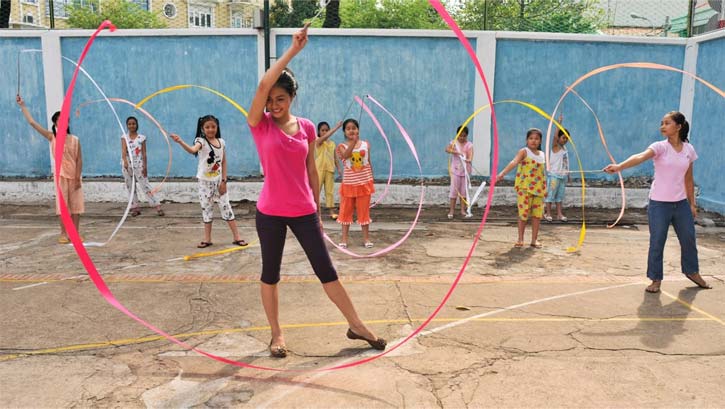

The number one problem with Saigon Electric, though, is that it tries to explore too many options at once and explores all poorly. Though primarily billed as a dance film, it fails in meeting the lowest of dance film standards. It is not a Vietnamese equivalent of Step Up, because Step Up actually contains amazing dancing. Saigon Electric has extremely amateur breakdancing and shallow portrayals of hip-hop culture. Dance scenes are filmed in a disconnected, paint-by-the-numbers music video fashion that is less about highlighting dance moves as it is about capturing fun angles. In fact, stylistic experiments frequently take precedence over cohesion; variations in color treatments and filming styles abound, as though the film lives in five-minute increments.

Adding to the film’s fragmentation are its half-witted plotlines featuring forgettable characters with pointless romantic interactions. Its wild predictability holds it down as well. At two distinct points during Saigon Electric, I was notably elated because events I had anticipated turned out to slightly — and I do stress slightly, as these scenes were of no consequence in the long run — deviate from my anticipations.

Saigon Electric may be the first film of its kind for Vietnamese youth, and its greatest value may lie in this fact. The cinematography is decent, the cast is cute, and the soundtrack, in isolation, is appealing enough — but all playing fields leveled and all socioeconomic and sociopolitical factors discounted, Saigon Electric is the worst film I’ve seen since last year’s Henry Of Navarre.

Seen at Seattle International Film Festival 2011