– Yoshi Sodeoka, on the influence of noise music upon his art

Mask of the Apocalypse: Sodeoka’s Occult Elements

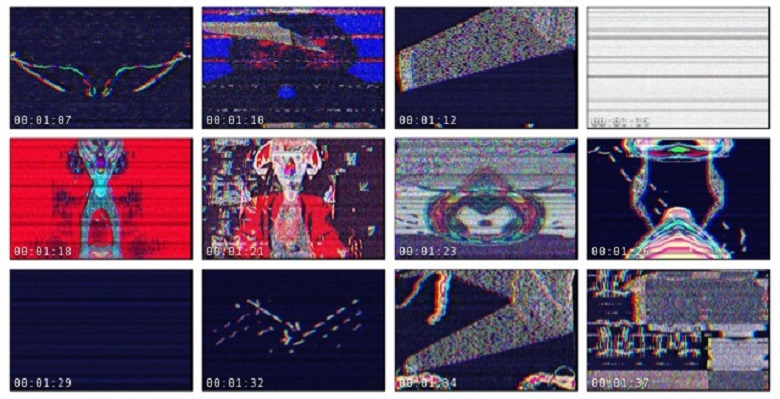

(Satanic Messages in Digital Videos © Yoshihide Sodeoka)

The most obvious manifestation of the noise aesthetic, which has been influential on Yoshi Sodeoka’s work, is seen in his use of fragmentation and information decay, though the artist maintains that glitch as a creative methodology is not a fixation of his. It is instead the expression of accident that is manifest in technology–initial explorations of failure in digital memory and computer behaviours from the ASCII series–which holds the strongest influence on Sodeoka’s work. By citing noise legends Hanatarash and Merzbow among his influences, Sodeoka offers some insight into the facets of stillness, ambiance, chaos, and impurity that permeate the artist’s work.

Themes and behaviours inherent to Japanese noise music infiltrate Sodeoka’s work, at minimum finding parallels to his tendencies toward grotesque symbolism, refusal of developmental composition, and expressions of disturbance. In an essay entitled Pulse Demons, New York author Eugene Thacker identifies how iconic Japanoise artists “bring together thematic elements of the demonic, the occult, and the supernatural with particular uses and mis-uses of new technologies”. It is easy to see where Sodeoka expresses themes of death and the occult in his own work–the ominous cloaked figure of the PSCYVOTV music video for Yeasayer, the faceless apparitions and homunculi of Evil Erector, or the disembodied, screaming maw of Psychedelic Death Vomit, although Sodeoka’s play with symbolism is not devoid of satire, as evident in Satanic Messages in Digital Videos.

Evil Erector

The visual language of occult symbolism in Sodeoka’s videos is diverse. Ambient and chaotic qualities inherent to noise are expressed in a kind of free jazz pixelated lightpainting. Evil Erector demonstrates Sodeoka’s preoccupation with sight; rarely offering a complete image, the screen depicts several morphing frames of a returning gaze. Originating in the machine, these eyes are absolute. As the artist plays with frame reflections, the faces are unnaturally divided into symmetrical halves, slicing the human guise with artificial, impossible identities. Hallucinogenic colours divide along the meridian of the third eye, at one moment degenerating into abstracted linear shapes, and returning the next to the human-like form, now more sinister in presence. Smeared reds suggest papal cloaks. pentagrams and halos place mythological iconography on the ambiguous figure, and outstretched hands extend in prophetic reach towards the viewer. Sodeoka’s visual degeneration in Evil Erector plays with the helix structure of DNA, the clinical blue of human shells, and phallic imagery that suggests of a darker legend of human conception.

Psychedelic Death Vomit and Devil’s Reign show further parallels to the occult obsessions of noise music. The psychedelic experience is exploited in order to intensify distressing or trance-inducing effects on the viewer. A face emerges in a primordial multiplicity, out of a spinning order of geometric shapes. At its center, infinite copies recollect into the single unit as quickly as they appeared. This presence seems far from entirely human. The translucence of its skin and closed eyes suggest an ethereal character — one that exists in a state removed from the opened eyes that receive illusion through terrestrial sight. Cosmic particles streak across the screen in a state of perpetual movement through deep space. The rings that erupt from the center of the frame suggest a sonic communication being relayed by the silent, sightless entity, in direct relationship to the collages of Sodeoka’s sounds. When the entity opens its eyes, devoid of pupils, the order allowed by the linear elements is extinguished by the increasing chaos of hovering objects. Sound and image decay in a final scream that retches and consumes in an indistinguishable stasis.

DISTORTION III / Devils Reign

The surreal style of Sodeoka’s use of symbolism, as in Devil’s Reign, reflects an aesthetic that leans heavily towards the grotesque motifs of the Chilean filmmaker and writer Alejandro Jodorowsky. Human presences are alternately distorted into fleshy liquids or augmented digital daemons, and Sodeoka overtly references religion once again, with his use of traditional symbols such as the halo, distorted pentacles, thrones, and the wanderer of the desert. Even the turbulent colors of every scene have a stained glass quality, like an occult temple seen through hypnotized eyes.

Echoes

Even within the pastel-hued work, Echoes, Sodeoka allows darkness to lurk against the vibrant colours of cosmic imagery. The flecks and striations throughout Echoes seem to reference the technological errors or insufficiencies of documenting the cosmos. The unseen and unknowable is always made evident, complete like the translucent face that reveals the cyclical nature of being in Psychedelic Death Vomit, yet inexplicable. It is an almost painterly quality that allows Sodeoka’s colour and light to attain its own symbolic status in his videos, playing with the discordance of perception in photographic image and ambiance.

Noise & Stillness

Aside from the overt references to the occult that are often inherent to the noise music that influences Yoshi Sodeoka, the artist also–perhaps subconsciously–communicates a preference towards minimalism, and the inverted significance of distortion and realism. The earlier mentioned influences of Hanatarash and Merzbow are iconographic of particular behaviors of noise in sonic form, in the musical context, which find their way into Sodeoka’s imagery.

In the essay Full With Noise: Theory and Japanese Noise Music, Dr. Paul Hegarty of University College Cork explores the work of prolific Japanese noise musician, Merzbow (Masami Akita). Hegarty refers to a phenomenon of exclusion, explaining it as a process that relies on isolation to determine the sonic occurrences that can be identified as noise. Noise music, as a genre, embraces the chaotic ubiquity of sound in all of its origins, whether this source in found in the manipulation of a musical instrument in unintended ways, sounds that originate from within the body of a listener, fragments from the periphery of the listening environment, and of course, accident in all of its manifestations. The identity of noise is then found to be the excess, the profane, the undesirable–the noise aesthetic coming into existence where the artist celebrates such unchoreographed presence.

Noise is no more original than music or meaning, and yet its position is to indicate the banished, overcome primordiality, and cannot lose this ‘meaning’. Noise, then, is neither the outside of language nor music, nor is it simply categorisable, at some point or other, as belonging exclusively to the world of meaning, understanding, truth and knowledge. Instead, noise operates as a function of differance. If this term is what indicates and is subsequently elided, in/as the play of inside and outside (of meaning, truth, language, culture….), then we can form another binary with identity on one side and differance on the other, but with this difference – that differance is both one term in the binary, and that which is the operation of the binary. This is what noise is/does/is not.

[…]Noise music becomes ambiance not as you learn how to listen or when you accept its refusal to settle, but when you are no longer in a position to accept or deny.”

– Dr. Paul Hegarty in “Full With Noise: Theory and Japanese Noise Music”

Through this divisive formula, that which is deemed either as excess or as the aesthetically profane is made the artistic subject. It is this focus on the occurrence itself, rather than the attachment of any representational qualities to that which is present, that permeates Sodeoka’s work. This is a rejection of a hierarchy of meaning between the distinct and indistinct, the singular and the multiplicity, the identity and the environment. Such principle is reflected in Sodeoka’s frequent use of stillness or non-narrative, as well as his fixation on imagery of dirt and brokenness–often to the effect that the distortion itself becomes the focal point. To consider again the broken sound of ASCII BUSH, it is evident how the artist retains a certain respect for the ability of distortion to speak more clearly than an unaltered image or sound artifact. Combining analog or digital encounters with glitch, and shocking manipulations of displaced colors, light, scratches, and distorted shapes, Sodeoka resuscitates the grime of visual culture as subject, message and muse.

The factors upon which the distinction between the graphic focal point and the noise is judged, are themselves determined by vast cultural influence. To again turn to Sodeoka’s cited influences, Merzbow is an extreme representation of the potential polarity in expectations and significance in noise aesthetics. Hegarty explains how Merzbow’s albums reflect sonic realities that are contradictory to Western ideas of expressing, perceiving and, in particular, appreciating sound — that is, systems that idealize musical structure, ordered presence of sound. Noise in the Western musical context, Hegarty explains in another essay, Noise Threshold: Merzbow and the end of natural sound, has traditionally been defined as an acoustic problem. In contrast, Hegarty quotes Akita’s publication Merzbook, “Japanese Noise relishes the ecstasy of sound itself”. There is no necessity to impose structure upon the whole experience of sound for sake of justifying its being, or even for assigning a kind of mathematical limit by deconstructing its presence with distinct musical identities.

[…] ARTICLE: YOSHI SODEOKA VIDEO ARTISTS INTERVIEW: PSYCHEDELIC APOCALYPSE IN THE DIGITAL REALM // for REDEFINE […]

[…] Yoshi Sodeoka Video Artist Interview: Psychedelic Apocalypse in the Digital Realm […]