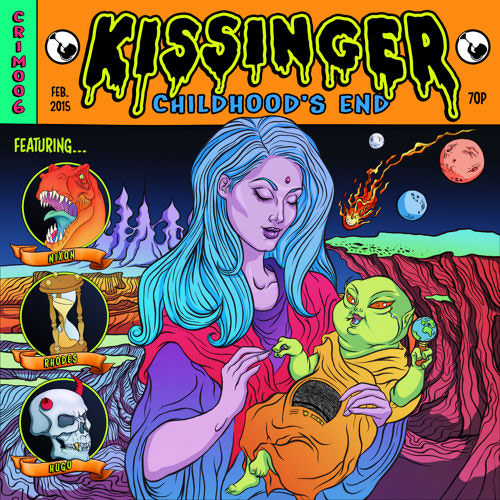

Childhood’s End, by the Croydon, UK producer Kissinger, is the first of a two-part space opera, soundtracking the loss of innocence for a planet, a society, and an individual. It shares its title with a famous sci-fi novel by Arthur C. Clarke, where humanity meets its doom at the hands of an extraterrestrial race that look like the Biblical devil.

Kissinger’s record, however, isn’t as bleak or as dystopian as Clarke’s novel, reminding us that growing up needn’t be all bad. You’re able to do what you want, go where you please, eat dessert for breakfast, stay up all night, and decide where you’ll live or who your friends will be. In a lot of ways, adulthood is just the best parts of childhood, refined and taken to their logical, and awesome, conclusions.

Childhood’s End takes the acousmatic properties of electronic music to its ultimate conclusion – weaving radio transmissions, slamming doors; breath and pulse, together with glistening organs, corrosive drones, and detuned digital voices into a cohesive patchwork of bricolage beats. The album shares a militant hyper-ADD-addled information overload aesthetic with vaporwave, juke, footwork, and grime, reminding us that there is much to be done, but that not all is lost. Technology can bring us much beauty, and while it can tear us apart, can bring us together as well. By honing and polishing the ragged, jagged edges of sound, Kissinger simulates this technological intimacy, by gracefully placing every piece on the grid, like a child hanging a precious emerald bauble on a Christmas tree.

Kissinger practices the same shuffling, loping garage two-step drum patterns as Burial, but while they are used to simulate the sensation of urban isolationism, in Burial’s case, Kissinger’s beats sound like evolving alien sound sculptures. The woozy heartbeat, breaths, and inhalations of “Best Times + Sun” are the best example of this, which sounds like a mile high wall of lungs, yet still manages to be danceable, somehow.

Childhood’s End by Kissinger is what it might sound like if the anti-gravity automaton from William Gibson’s classic cyberpunk novel Count Zero could also pick up radio signals, along with burnished ephemera from the Earth, to build stunning, polished bricolage of sounds. Rather than lament the loss of our innocence, and trying to crawl back to the garden, Childhood’s End encourages us to embrace and celebrate adulthood.

Making peace with the technology around us — to use it, rather than be used by it — could lead us to became the caretakers of the garden we have always been intended to be. Instead of a distraction or escape, our interconnectedness could allow us to listen into a Brazilian rainforest, which may lead to protective feelings towards the high-pitched chirp for a poison arrow tree frog. Or Twitter data being used to combat world hunger and disease. We need not be deluged by digital data; we don’t have to drown and we’re never going to keep up. Instead, with Childhood’s End, Kissinger remind us to take what we want, and disregard the rest. Much like growing up.

Ω