Photo credit: Houston Cofield

Addressing Gender & Hypermasculinity

“As a rapper who exists in hip-hop spaces, which are inherently hypermasculine — at pretty much most times — I feel like self-awareness isn’t always there, and sometimes that’s the best way to get the message across through my art, especially being that I am masc-presenting, although I identify as nonbinary,” says Santinac.

For their latest six-track EP, Kamakiri 222, Santinac explored themes of “themes of triumph, and empowerment, defiance, rebellion” by working in the spirit of “unbothered.” They had been in a creative rut and unsure of their next steps, when a Seattle hip-hop show featuring The Alchemist, Boldy James, Action Bronson, and Earl Sweatshirt refreshed their perspective. Action Bronson, in particular, had been inspiring.

“He didn’t really seem to care about anything that was happening outside of that stage. He appeared very comfortable in his body, and that reminded me, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s what it means to be a rapper. You’re already cool. You don’t have to explain yourself; you just have to be,'” Santinac explains. “I wanted to encapsulate that energy, but also in a very sassy way.”

One way that this sassiness is captured is through curated audio samples. One such clip, used on “My Lesbian Barber <3,” comes from a 1985 Grace Jones interview with the Australian current affairs program, “Day by Day,” where she has to defend herself from a white interviewer who asks if she is “aggressive” or “masculine,” and whether he should be afraid of interviewing her. In the track, Jones is heard saying, “I like being both [feminine and masculine], actually… it’s not being masculine; it’s an attitude, really. Being masculine, what is that? Can you tell me what is being masculine? I just act the way that I feel.”

This clip resonated with Santinac, who explains, “Grace Jones is a huge example of my personal philosophy on not necessarily gender, but the way that I perceive and navigate femininity and masculinity, which for me, are two different forms of the same energy… that, for me, is what that soundbite was all about: just Grace Jones being defiant, absolutely, in her own philosophy about gender identity.”

While Grace Jones may speak volumes with her quotes, some of Santinac’s references may be a bit more hard to entangle; their meanings may be more veiled. This is particularly true when Santinac pushes the boundaries of making people uncomfortable with their music. A repeating refrain on “Simp x Fried x Rice,” for instance, states, “Don’t talk to me unless you sucking dick,” backed with soulful vocals echoing the same in a femme voice, in an almost joking manner. The track also ends with the sounds of hentai, or anime porn.

“[“Simp x Fried x Rice”] usually makes [cisgender heterosexual] men feel very uncomfortable… at least, until they notice femmes singing along, and suddenly, their demeanor changes,” Santinac explains. “For me, it’s all about defying hypermasculinity and creating dialogue around the discomfort of men who don’t often consider the discomfort they create within hip-hop spaces both in and outside of the music.”

When asked how they might deal with misinterpretations of their intentions, Santinac responds, “Sometimes, I wonder if my lyrics have some sort of enigmatic, members-only (if you know, you know) feel to them, and this stresses me, because naturally, I want everyone to digest [them], but I also know that I can’t control how others interpret my art, and art isn’t always pretty to everyone.”

“I can only leave the door open for potential discourse,” they add.

Drawing Atypical Influences from an Atypical Upbringing

Ash León’s creative process is in part informed by collaborations, including their work with iNGudCo, an artist collective they helped co-found. Artists they work with in the collective include Spek Was Here, Dame Mufasa, Austin Crui$e, theGoddessie, and StarBunny. In particular, Santinac describes their friendship with Spek Was Here as very unique — one where the majority of their time is spent doing “non-music things.”

“We just love watching movies together — to the point that even when we are working on music, there’s likely some film playing in the background,” says Santinac. “That’s how we discuss concepts with each other. When we’re talking about what type of sounds we want, we talk in film. We mention film directors; we talk about the different textures that we experienced watching something and how we can translate that sonically.”

Along the way, they have amassed a trove of sound bites that end up being incorporated into their work. This approach takes influences from plenty of niche film genres — whether it be science fiction, samurai, Blaxploitation, or spaghetti westerns — because Santinac believes these aesthetics feel otherworldly or timeless.

“A lot of the time we lean towards more grittier, dustier, grungier textures when it comes to what we’re creating sonically, because the implication is the illusion of timelessness — that you really can’t tell what era you’re in when you’re listening to my music,” Santinac explains. “For all you know, you could be 300 years in the future, and you’re hearing something from back when, or this could be broadcasted from an entirely different planet.”

This otherworldly feel is certainly also highlighted by influences from comic books and anime, which are just fundamental to how Santinac was raised. Born in 1990 and self-identifying as a “baby millennial” Santinac explains, “By the time I reached middle school, Adult Swim was pretty much my older sibling, and all of the programming that they would air… definitely altered the trajectory of my life… because that is how I even really, truly discovered what anime was.”

These early interests in anime bloomed into fascination with Japanese culture at-large, but Santinac cites some early identity struggles from spending time with their grandmother in Warwick, New York — which was predominantly white and upper middle class — and later moving to Memphis, Tennessee for high school. Once in the South, they found that certain types of artistic tastes they had developed were no longer popular or accessible.

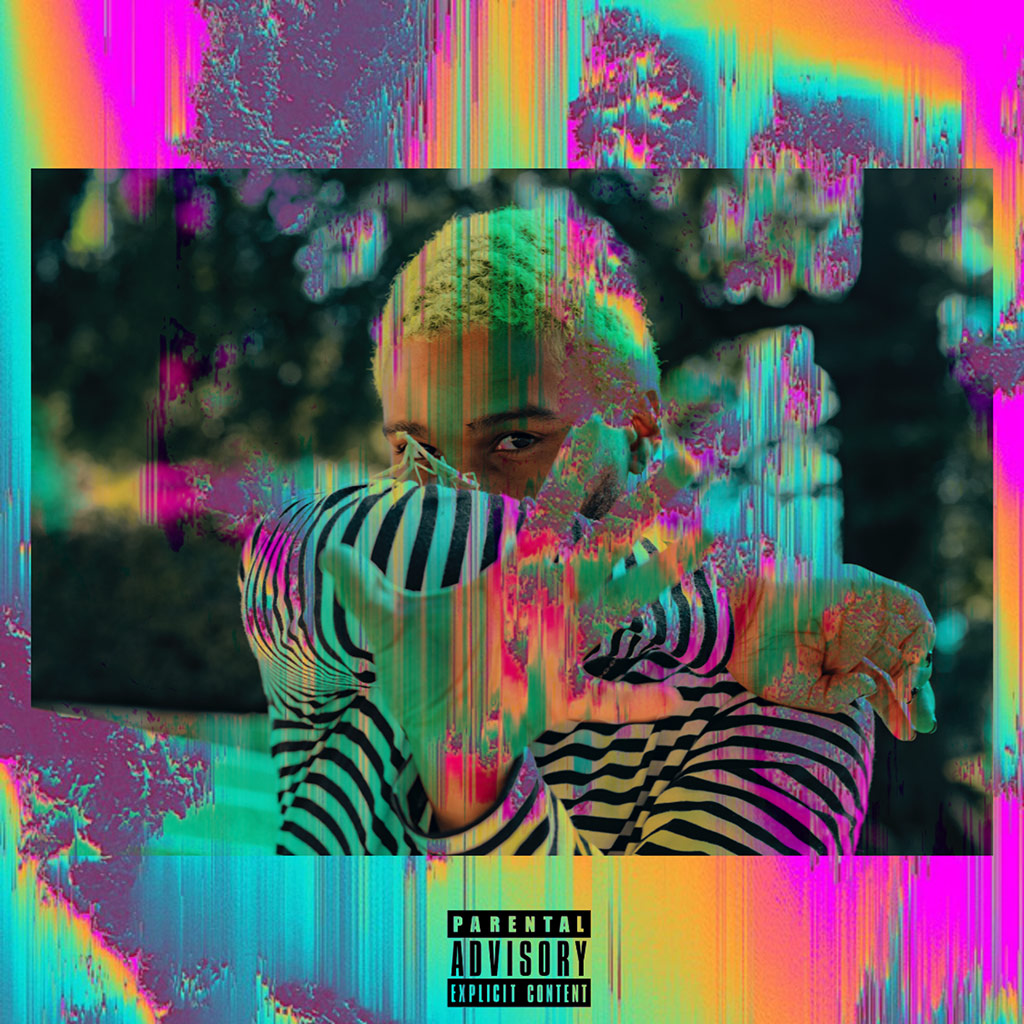

Album cover artwork for an upcoming, untitled EP

“[Living in Warwick was] how I was able to gain access to a lot of my nerdy interests, and why a lot of those same nerdy interests were seemingly culture shocks for some of the other black children that I eventually went to school with down south,” Santinac shares, reflecting on life in the early ’00s. “This was before social media. Impoverished communities of color that barely have access to grocery stores (food deserts) aren’t very concerned with the existence of comic book shops or graphic novels.”

“That’s not to say it doesn’t happen,” they quickly add. “HELLO WU-TANG CLAN.”

Still, developing such a complex identity from such a young age led them to wondering how to be authentic while still taking inspiration from multiple cultures.

“It’s important to me to not only have identity, but be authentic in that, so a lot of those references just come from my inner child and the things that not only fascinated me back then, but because of that fascination, I still know a lot about today,” Santinac explains. “[I also think about] cultural exchange versus appropriation. I feel like it’s possible to enjoy something, say that you like something, [and] pay homage to something without wearing it as a costume.”

With the Kamakiri 222 EP, a real life incident with a praying mantis played a role in the final artistic output. In Japanese, the word kamakiri translates to “praying mantis.”

“My favorite part of this entire experience is that a praying mantis that [landed] on me during a photoshoot… it wouldn’t leave, and I love that. I feel like [it’s] the superstar,” says Santinac. “I looked into what the praying mantis symbolizes across different cultures, and the duality it holds in Japanese folklore resonated with me — a symbol of great courage and fearlessness, but also cruelty and merciless. The Angel number 222 can be interpreted as a symbol of balance, harmony and spiritual alignment. That’s the story I’m telling from the first track, ‘Helios 🙂,’ to the last track, ‘Ichiban!‘”

Album cover artwork for Kamakiri 222

Pushing Boundaries & Manifesting Trippier Things

Kamakiri 222 was born out of a particularly difficult time; as a result, Santinac used the record to intentionally transformed moments of darkness into moments of empowerment.

“I don’t like to rot… some days just aren’t good days, and some moments aren’t good moments, and they can last,” reflects Santinac. “It was a rocky summer, and I just felt like the best thing I could do in that moment was to shift frequencies and put that energy into just… well, affirmations,” they continue. “I won’t say positive, but just affirming that, ‘Hey, I’m here. I’m not going anywhere,’ you know? Bad bitches don’t die, so let’s get it.”

Santinac is presently working on a number of upcoming releases, and they consider Kamakiri 222 to merely be an appetizer on a long string of dishes which still need to be served out. Coming next, in Fall 2023, is an as-of-yet-untitled four-track EP which continues to expand upon gritty, grungy textures and metaphysical themes galore. Other releases are in the pipeline as well, such as an EP inspired by the Japanese revenge film Lady Snowblood.

“I feel like I experience music in colors, and there’s still an entire kaleidoscope that I have not written about yet — that I’ve not manifested into content that other people can digest and enjoy,” they explain. “So that’s really my focus: what boundaries can I push? How can I make this even more trippy and psychedelic?”

Ω