Coal mining excavator at night. (Credit: John Atkinson)

Q&A Interview with John Atkinson

You went from living in Brooklyn to doing this residency at Ucross, which is pretty remote. Grounding us, I’m wondering if you could describe what it was like initially to enter into that region of the country? Can you set the stage for us?

I just had this idea… I’ll just drive there. It’s a decent amount of driving, and it’ll be a few days, but I can camp en route… I’ve traveled a decent amount in my life, but not much in the Midwest, and none in the High Plains.

I came up with a kind of itinerary based around energy infrastructure. The Department of Energy has these great maps [through the Energy Atlas]… you just see all kinds of energy stuff that is wherever you are. [Such as:] where are the hydro plants in my state? Wind farms? Power plants? You can see it all…I spent a couple of days on Google Maps, figuring out how to optimize my route… and I was learning about the region a bit.

Also definitely spent — especially in the Dakotas — time learning [and] listening to Audible audiobook of Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee… At first, I was mostly going through Native American lands and learning about the Sioux and everything that went down there. Which I was aware of, but when you’re listening to it for hours and spending four of them being like, “Oh, my gosh, this beautiful landscape is just the zone for so much horror and trauma and evil.”

[TOP] Open road, surrounded by grasslands; [BOTTOM] Train cars carrying coal. (Credit: John Atkinson)

It really sinks in?

Yeah. No doubt…

I was [also] reading John McPhee… he’s kind of an old American science writer; he wrote about geology a lot. So I was learning about the geology of Wyoming, especially, which is just crazy. Nothing could really prepare me for what it looked like, and the feeling of deep time you get out there…

Most of what we’ve learned about geology is from the development of the highway system. We just made all these road cuts, and suddenly, the geologists all went there, like, “Oh my God, look at these layers…”

This is how we learned about the world: just by blowing it up sometimes. And about ourselves… So I was really primed… just trying to get into the history, both in the past few centuries — but more the deep time aspect. The kind of resources that are millennia old. These fossil fuels and stuff that are still just shaping the entire region’s economy…

I’ve worked a lot in policy and stuff. Wyoming is the smallest state, I think, population-wise, in the country, and some absurd portion of their budget is just royalties on fossil fuel development…

During that week, I checked out the coal mines. [They] are really a centerpiece. [The] experience of it: that was one of the most magical [moments]. Top three nights of my life.

The whole day was so fucking crazy. I didn’t even know where I was going to sleep, but it’s in the middle [of Thunder Basin National Grassland]. You can camp anywhere in national grasslands, and it’s right in the middle of literally two largest coal mines in North America. [There’s] this whole long road that you drive down, and you see these huge things… and it’s not like coal mines in West Virginia, [where] we think… it’s out of holes [and] you’re going underground.

They have a saying: all you need to do to mine for coal in Wyoming: all you need is like a nine-iron. It’s just right there in the dirt. It’s just these huge open pits, and it’s all very mechanized — again, in contrast to the West Virginia [or] Appalachian coal mines, where you have a lot of people doing stuff in there. It’s just all this hulking machinery going around. It felt… sci-fi, planetary, building a colony on Mars… just the scale of it.

And you’re driving past these things; it’s like you’re driving for an hour, and it’s just endless on either side. I was like, “How do I get close enough to record some sound?” so I would hop out. I was trying to line up tours of it, but I was unable to secure one. I was emailing, calling — and it’s like, “No, it’s not really a thing.” So I did it kind of DIY. I was sneaking around, hoping they don’t think I’m a terrorist or something. I’m just a nerd. I’m just this sound geek.

I got kind of close in a couple places. There was this very one particular turn on the road that goes right up by the lip of one. For the most part, you’re kind of away from it. And I had never dropped a fucking pin on a Google Map in my life, and I was like, ‘I’m gonna just drop a pin right here.’ And I drove all day. It was raining; there was a rainbow.

This is a long story. I’m sorry.

Oil refineries. (Credit: John Atkinson)

It’s interesting, actually. Which is what I wanted.

I’m like, “Okay, I’m passing through the coal mines,” and there’s a big wind farm that I wanted to pass to the south, but I’m driving down, and there’s all this rain while I’m going by the coal mines, and the clouds are parting. There’s a rainbow and a big field of wind turbines. I’m crying. I was having a moment. I might have been stoned a little bit. I was just like, “This is what it’s all about.” I’m experiencing this full thing; it’s God coming and being like, “This is what’s up; this is what’s happening.”

There’s a lot of wind turbines out there… they’ve barely scratched the surface on that, but I mean, Wyoming has, I think, the biggest wind resource of any state in America. It has enormous potential for that… and the sunset was beautiful. I love sunsets; I’m never gonna end a trip if it’s in the middle of a good sunset. So I just kept driving, and then, I passed this oil refinery, which wasn’t even on my map, but it was a beautiful sunset by this vibey oil refinery, which is where I got some of the sounds for the third track, “Casper.”

And then I was going to just spend a night… but… it’s kind of a little mini oil boom town; the hotels are $200 a night minimum. Everything’s booked up, and I’m like shit, “Okay. I’ll just drive back to the coal mine and see if I can find a place to camp.”

It’s one in the morning, and… I go to where I drop the pin. I find it and… it’s totally empty. Quiet. I just pull over on the side of the road. I’m right there. And the machines go all night, and they’re digging stuff… the second track, “Black Thunder” — all that’s based on this most magical field I’ve ever taken… [for] 15 minutes, I was just standing there, transfixed, being like, “These sounds are incredible.” There’s this big crane with spotlights going back and forth, and I can barely even see in. It was just looking so cool.

I was finally getting very cold at that point… it was really windy and shit. So I was like, “I guess I’ll finally just kind of off road…” and I wake up just in the middle of this field. In the night, I can see around my tent, and… in the distance, there’s still these flickering lights from the coal mines, and just a national grassland in the middle of it.

It was an incredible night, and then I got to Ucross after a week of those kinds of experiences — and after that one I just described at length in particular.

I saw a bunch of bison, also. The Badlands were awesome; the Badlands were so sick. I got some [field recordings of] some bison, some prairie dogs, because I wanted to bring in the nature… It’s linked, but I’m more of an energy guy, in terms of: what I do for work. Trying to change that side, instead of minimizing the fucked up stuff we do [related to nature]. I wanted to really foreground the energy. The industrial aspects of it, in various ways.

[TOP] Sunset (Credit: John Atkinson)

That makes sense. I know that you’re supposed to propose an idea of a project when you apply at Ucross. Did that experience change your trajectory a little bit? I’m curious.

When I applied, I was like: I want to do site-specific stuff that engages with Wyoming’s natural [surroundings] as well as its role as a big energy-producing state. But I didn’t really have that firm of an idea around it until I was actually driving. I didn’t really know if I was gonna get anything. [I was like,] “I really hope I get some decent sounds.”

I got there, and there’s this magical trip, and I rolled up to Ucross, and it’s this extremely charming little mini campus. Everyone there’s super sweet, and I’m surrounded by all these like real ass like, writers, artists. The only other musician… was a dude who wrote Broadway songs and stuff. So I was like, “Okay, what am I doing here… how am I going to translate that idea of something that engages with… both the environmental and the energy side of things?”

I’ve gotten all this raw material, and the first day or two, I was just going through, uploading all those samples; listening to them figuring out the best parts…

I’ve never done music full-time… going into it, I was like, “Oh, maybe I’ll do some hiking; I’ll see the area and stuff.” But once I was given the opportunity to just work on music all day, I was like, “Fine, I’m gonna work on music all day.” I’m gonna give myself time to do the super boring but important stuff that I often don’t make time for when I’m just doing music for a few hours of the day — just in terms of going through all those samples and really marking where they are. What are the good parts? Really listen. Give myself this space to listen; engage a little bit more deeply with the field recordings.

It wasn’t my first time using field recordings, but it’s definitely the most in-depth and seriously I’ve ever thought about them thematically… instead of just making some cool sounds, I was like, ‘I need to make this kind of cool sound,’ and this is the recording I want to use for it… and making little various kinds of processing techniques and signal… plug-in chains and stuff that I built.

Can you tell me a little bit about your process for making virtual instruments, and why that methodology speaks to you?

My keyboard was banished from my rig for years, because I was like, “It’s too linear; it has its history on it.” You’re just gonna put your fingers in places where the right notes are, without really thinking about it. So I replaced it with stuff that’s kinda like a touch controller — that incorporates pressure as well, as X/Y — so every finger could kind of control three different [variables].

You could really lean into it and be expressive that way. I got this cool video game controller for gesture control. It kind of made it so that I can… bring sounds up and down to change a parameter.

Almost like a theremin controller kind of vibe?

Yeah, like a theremin. But instead of just like, “Oh, it’s a note…” it’s [more]. That’s what you hear a lot on the album — a lot of really micro-edited things that flick in and out. That’s because I… [have] super granular control. Compared to a twisted knob, where I can do literally one thing at a time with my entire hand, now it’s like… with one hand, with the pressure, I’m doing a bunch of different things.

It kind of almost goes into the energy environment distinction or dichotomy, where I want to make music that is super digital, in a way. I want to make music that acknowledges the material reality of our world. Not that physical instruments or synthesizers and shit aren’t material, but I kind of want to make something that is transforming… working with reality. It’s all field recordings on it. It’s not a single synthesizer; not a single instrument. Everything is made from these sounds that happened at a specific time and place that I recorded myself — but they’re all going to be going through this digital process that twists them and kind of makes it uncanny or unfamiliar.

I think this also speaks to the experience of both our reality and the kind of relationship between… the energy system in our world, right? It’s like: okay, we’re gonna dig up these rocks that were from dinosaurs a few million years ago, and we’re gonna set it on fire, and somehow, that’s going to turn it into another thing, and suddenly, I’m talking to someone in Seattle. It’s pretty wild. It’s very unnatural. I want to do something like that.

The final ingredient — which I still haven’t mastered is… instead of drawing out notes and lines and stuff, I want to be able to engage with the sounds in a way that’s more connected to my body…

I got this breath[-based] MIDI controller. I look like a total freak, because it measures both the breath and your bite — but also has this little head thing, and it measures like the X/Y orientation of your head as another input. I played a show for that East Portal album duo I did last year, and… people are like, “Oh yeah, you’re really into the performance,” and I’m like, “Oh, shit; should I set a disclaimer?”… It’s not me. I’m doing that to make the music; I’m not just being dramatic…

Well, first and foremost, you’re doing what you need to do. You want to record the coal mine and turn it into an instrument, and that’s what you gotta do.

Honestly, having the experience of recording that and being there makes the whole thing worth it. If I had to do all this work just to reverse-engineer having experience? Very inefficient, but it really helped me appreciate what I knew on paper, but…

Not that I’m ever asked this much so directly, but it’s kind of like a lot of what people feel like, ‘Oh, you work in energy; what do you think about X, Y, or Z?’ I usually fall back to some variation of: the thing you need to understand is… it’s so big. Just the amount of stuff we dig up out of the ground; the electricity grid. The way all this shit works is unfathomable. And it takes a long time to change and all that stuff…

I’m not a guy that’s out in the field working on oil rigs and shit. I’ve never worked for an oil company, but seeing this big ass coal mine that I knew was really big? Holy shit… It’s so big and it’s awesome, in a way… obviously, I’m talking about it, right?

I’m not like, “It was a horrifying scar on the land, and I was so morally repulsed, and the whole thing should be ended,” and whatever. You spend time in Wyoming, and they’re pretty proud of their coal mines. It built their state. There are real people that work at these things, first of all, and have their livelihoods tied up in it, and I gotta respect that.

And also, I use a lot of electricity. If there weren’t these coal plants, I wouldn’t have electricity Ucross because Wyoming is mostly coal fired… I’m always like: let me implicate myself in the situation.

The phenomenological experience of just seeing this stuff… there’s an intellectual part of my brain that’s horrified that we’re still using all of this stuff. We don’t need to be mining all this coal, still! There’s better solutions out there… and then there’s a part of me — that fucking five-year-old boy who just wants to look at cranes — that’s like: ‘Wow, isn’t it fucking awesome that we can even do this?’ I can’t believe that human beings are capable of doing this…

I feel awed by what we’ve built and how we’ve extracted shit from nature and built this crazy fucking weird world… I don’t like a lot of aspects of it, but [it’s all] I’ve ever known, right? If I’ve experienced joy in my life, it’s in part because of fossil fuels, right? It’s not the one reason I experience joy, but it’s the only reason I can share with you…

Both can be true at the same time. We can enjoy all these things, but also realize all the negative aspects.

There’s a lot of things that arts can be, but that’s one of my favorite things [about art…] kind of like exploring ambiguity in a safe space…I get why energy is very political for a lot of people, and… for me, it’s super important to get involved in the political side, but it’s also more. It’s about the human story…

As a civilization, we’re at the point where we realize that, “Man, we’ve really fucked up a lot. This is kind of crazy, and we really got to do better.” And I’ve had that thought about my own life many times, and I’ve gotten better in some ways, but it’s hard. Takes a long time to change. You don’t appreciate the gravity and inertia of your life. When you get a few billion people together, that’s just the same thing on a bigger scale, ultimately.

Humans are messy, so inevitably, things we make will be messy.

We’re big messy idiots.

Yeah, we’re just children, really?

How did we build all this shit?

It’s so weird. But again, it’s weird compared to what? This is all I know.

Good points. I’m curious. Yeah. You mentioned the coal mine sound obviously, but what are some other field recordings sounds that really stood out for you as memorable?

All the stuff on the album is all from field recordings, right? But some of it’s treated in a way that makes it sound more like a synthesizer — less recognizable…

On that track, “Spiritual Electricity,” at the beginning… the insect buzzing… I think it’s cicadas…

Oh, okay, that’s not what I thought at all.

It’s just bugs. I couldn’t see them anywhere. It was just in the air in Wyoming, which is at [Devil’s Tower,] the first National Monument in America…

Right after that, the bison… those low sounds — those warps — are bison recordings from the Badlands, maybe…

And actually, I camped at that Badlands site… there was a big prairie dog village in the middle of it, so I got some great prairie dog recordings the next morning, which are always fun.

They’re very entertaining for sure…. I love your trip. Your trip sounds amazing.

Having all the time to work a Ucross was such a blessing and really deepened my practice… but the trip going in and out [of Wyoming] is just like, shit. I’ll remember it always…

Is there anything else you would like to share about the record?

Another kind of idea that I wanted to get on there was this concept of: change in the energy systems… the systems are so big. There’s so much inertia; it changes very slow.

Alot of the songs are kind of meditative and in a certain vibe… the build or whatever doesn’t really change, but… energy change is really slow, except sometimes it’s really fast. That happens at the level of the resources itself.

When you dig up coal, it’s these processes, and you combust it, and it spins, and the combustion happens on this timescale, and then it spins these huge turbines at a power plant that spin it a certain rate, and it takes like 15 or 20 minutes to get up to full speed and down, and the fuel itself took 6 million years to form.

So there’s all these interactions in the physical processes, as well as the social processes of… the fact that solar got so cheap so fast, and batteries got so cheap so fast, over the past 10 years. [It] is something that… people talk about in our industry because we still can’t believe it… Or if the grid blacks out… all of a sudden this whole thing comes crashing [down].

On pretty much all the songs — especially the first three — there’s really a focus on trying to evoke both the slow, big build of these big systems, and then sudden changes in momentum and transformations of state. From the solid coal to this burning gas which then turns into electricity…

Here are four vibes that resonate with me about how the energy system is and how it changes — and our experience of it…

There’s a lot of ambiguity; there’s a lot of beauty and density of meaning.

Ω

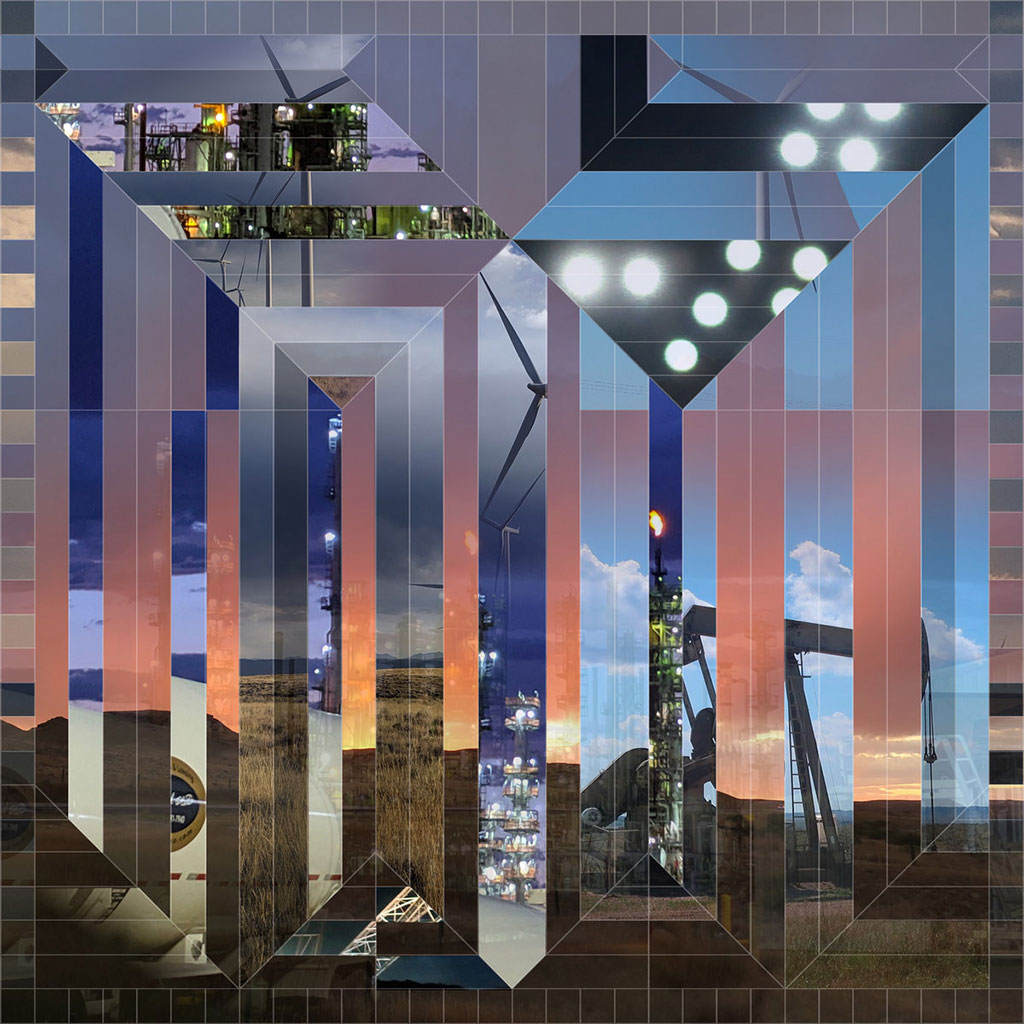

Cover art for Energy Fields. Artwork & Layout by Francie Chang; photography by John Atkinson