“Music for me is ooooold Tom Jones,” croaked the homeless man with a weathered smile. He’d boisterously wandered into Robert Henke and I’s conversation a moment ago. He mumbles a few other lines — classic no doubt, but indecipherable — before we tell him that we need to get back to our interview before Henke’s lecture that evening.

Jarring as it was at first, I felt that the old man’s last quotable words were hilariously relevant to the talk I was having with Henke. As Henke and I talked about the evolution of music production and consumption as it relates to the tools involved with both, the old man was a reminder of just how far everything has come.

Henke has much to say about the use of engineering and interface construction as creative mediums — ones that are practiced by unsung hierophants of the esoteric arts of electronics and software development. Being the last man standing of influential minimal techno pioneers turned multi-sensory space voyagers, Henke is a learned man on this subject. His electronic dance project Monolake is world-reknowned for its 6-channel, audio-visual performances, and his work as one of the principle designers behind Ableton Live has contributed to making the music software an industry standard.

One could even say that Henke has had more influence over the last ten years on the way millions of people create and perform their music globally than any bigger-selling musicians or producers, simply because he helped build the instruments we’re all using to bring our ideas to life. Not that he would jump to point that out, mind you; Henke isn’t quick to list his accomplishments, but he is sincere in noting his place in the lineage of artists who have fashioned their own tools. Out of the joy of solving puzzles and the need to make that sound, image, etc. their own way, those engineer-artists have inadvertently come up with novel technologies that the rest of us can not only enjoy, but use to create our own works.

“I see a lot of similarities between fascinating engineering and fascinating art. Both have to do with craftsmanship; both have to do with finding a simple solution for a complex problem. And it has to do with elegance and needs inspiration. It’s underestimated how much inspiration goes into good engineering, and how much artistic thinking is involved in good engineering.” – Robert Henke

Troy Micheau (REDEFINE): I’m Troy Micheau; I’m interviewing you for REDEFINE magazine. This is Robert Henk-eh… am I pronouncing your name right?

Robert Henke: Yeah, perfect! But I’m not very anal about my name, [even] if some people say Henk-ee… it’s just letters.

Performance Works

Monolake Live

Monolake is comprised of Robert Henke and visual artist Tarik Barri, with whom Henke has been collaborating since early 2009. Ghosts In Surround presents the material of Monolake’s album Ghosts ghosts in a surround-sound experience with real-time generative video. Their goal is to create an audio-visual experience that is “aimed towards an audience that can move and react”, rather than a seated audience.

Atom

Atom is a four-channel surround sound installation supplemented by an eight-by-eight grid of 64 illuminated and inflated gas balloons. Positioning and illumination of each balloon creates a dynamic sculpture that moves in time and dynamism with the music. It is a collaboration with Christopher Bauder.

Robert Henke

As a solo musician, Henke has undertaken many multichannel and improvisational performances. A list of his more recent and notable projects can be seen on his website.

On Ties Between Art & Engineering

Troy Micheau: Yeah, it’s true! So, read a lot of interviews with you, and a lot of times you call yourself a sculptor or an engineer, and your work with music, as well as Ableton and things like that, would reflect that also. How would you characterize your identity as an engineer and your love for mechanics and detail with your appreciation for abstract and very open-ended art?

Robert Henke: Well, I see a lot of similarities between fascinating engineering and fascinating art. Both have to do with craftsmanship; both have to do with finding a simple solution for a complex problem. And it has to do with elegance and needs inspiration. It’s underestimated how much inspiration goes into good engineering, and how much artistic thinking is involved in good engineering. And, of course, it’s underrated how much engineering goes into pretty much every successful kind of art. So, for me, there’s not so much a difference in the working method. There’s more a difference in the goals you want to achieve. Engineering mostly wants to find solutions – general solutions – which are useful for a lot of people. Art doesn’t normally want to have a solution for a problem. It’s a different kind of thinking.

Troy Micheau: On a side note, I was talking to a friend who was at the [PNCA concert] last night, and we were talking about people who would’ve designed the presets in synthesizers — back in the ’80s, specifically — and saying that those guys, as engineers, were actually probably the most influential on the sound of electronic music for a whole decade and probably even more than that. They are not people that we generally know very well, yet their presets set the tone for a lot of things. I’ve read about you talking about the 808 before, and what the circuitry looks like in there.

Robert Henke: We could talk about this more, if you’d like . If you want to go more in detail — because I did find it fascinating how many people are involved in an artistic process who never shows up in the public notion. I’m always surprised when it comes to, let’s say, bigger multimedia art. In the public, there’s very often the notion of a single artist doing it, because there’s the big name at the exhibition. In fact, there’s a lot of people working for this artist to enable this art. Very often, it’s simply omitted because it doesn’t fit in the public perspective of the genius artist. In a way, the faceless engineer who’s building the synthesizer therefore is creating an artifact which just enables art. [It is] of course equally important in the whole game, [but other than] in a very rare exception situation, this person stays invisible. I don’t think we know who actually built the 808. From all that is known in the public, the circuitry is not from the Roland founder himself, as far as I can tell from reading his biography and other available sources. So it was some other person, or a group of persons at Roland, who made these decisions of how this thing should sound like. And those are [such] influential decisions. And there’s so many of those things going on where we have no idea.

Troy Micheau: There was an exhibit at a museum here last year that was all about video games going from the ’70s up until the early 2000s, and it displayed the names of the designers very prominently. It was like this art exhibit that was all about showing off these guys and saying, “Nobody knows who made these, yet all of these are all part of our childhood and really helped develop our world views and our interactions with technology.”

Moving on from that, though. You work a lot with arrangements and dynamics more so than song structures and things. I was wondering how — or if — this reflects your general thoughts on time and the experience of time. Last night, you were saying when you got to the end of your piece, you felt like, “Oh, I don’t really want to stop now, but it just seems like the right spot.”

(At this point, the old homeless man steps in for a sustained conversation and ends with, “Music to me is Old Tom Jones. Cat Stevens. But I’m older.”)

Troy Micheau: That break actually reminded me of a thing that I wanted to ask about. You have a laser light show coming up.

Robert Henke: I’m talking about this excessively tonight. Yes, and it’s the biggest thing I’ve ever done, so I’m pretty excited about that. Back to the question about time. I have a very strange relationship with time when it comes to music. I, for instance, have a serious issue with memorizing melodies and things like that, which drives me up the wall. So, playing in a band was always a big challenge because I always forgot about things and I always needed to write things down. On the other side, I have a really amazing memory for spatial things, so I feel that, in a way, I am living completely in the now. And my approach to music is probably shaped by that. I give up doing things which, in the creation process, need me to memorize long melodic movements and things like this, and instead work on the evolution of timbre, which I can for some reason much easier grasp. So I guess this is, for one reason, why my music is what it is.

The other is — I just like generally the idea of music as a state. This was something which always fascinated me with early techno music, where you go into a club and you lose a sense of time. That there was repetition, but repetition is meant to be endless. That’s the whole idea of the endless mix. You go in a dark basement; there’s no lights, so there’s no hint if it’s morning already or not, and there’s no clock on the wall, and no one cares. I found this extremely fascinating, and later, I understood that this idea of music as an endless situation is a very old one. Basically every kind of ritualistic music works the same way. For me, the kind of rhythmic music I’m interested in and my drone soundscape work are facets of the same thing. They’re both endless; they’re both not meant to work as three-minute radio pieces. So, rhythm is just another — a special case of timbre to me.

ROBERT HENKE INTERVIEW CONTINUED BELOW

Installation Works

Fragile Territories __ 2012 – 4 WHITE LASERS & MULTI-CHANNEL SOUND

Fragile Territories __ 2012 – 4 WHITE LASERS & MULTI-CHANNEL SOUND

Henke’s most ambitious installation to date, Fragile Territories uses a series of powerful industrial-grade laser beams onto a thirty meter wide by six meter high wall, coordinating bright shapes with changing sonic atmospheres. The installation is supported by Laser Animation Sollinger and is currently installed at La Lieu Unique in Nantes, France.

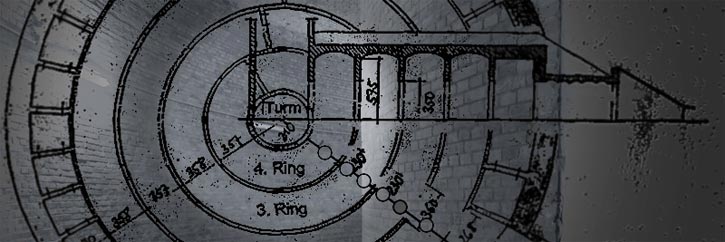

Eternal Darkness __ 2012 – SITE-SPECIFIC SOUND INSTALLATION

Henke was given the unique opportunity to create a site-specific sound installation in Berlin. It was housed inside an abandoned water reservoir full of unpredictable sonic behaviors, which created massive low-end frequencies and bounced sounds off walls in endless echoes. The installation is on view through September 2013.

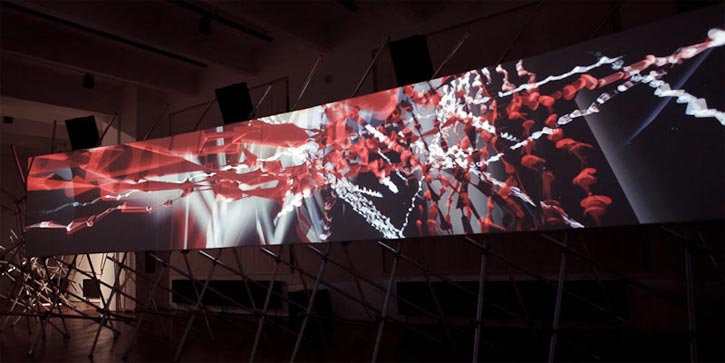

Fundamental Forces __ 2011 – ULTRA HIGH DEFINITION VIDEO & MULTI-CHANNEL AUDIO; COLLABORATION WITH TARIK BARRI

Henke and Monolake partner Tarik Barri collaborated on an audio-visual research and installation project which focused on “movement, acceleration and the interconnections and attractions between visual structures and sonic events, we as well as the underlying mechanics in each of the domains.” Mathematical operations led to the emergence of sonic structures and visual shapes, which were then transformed by further code manipulations. It has been on view in Berlin, Graz, Vienna, and Montreal in 2011 and 2012.

“… You have two choices: either you insist on playing in darkness, like the Autechre solution, which is a very valid solution, I think — or you find someone or [have] some idea on how to incorporate video in some way. This is just the path that I followed the past three, four, five years as far as Monolake is concerned.” – Robert Henke

On Audio-Visual Performances

Troy Micheau: I’ve seen you refer to your work as sculptures, talking about them in a very visual way. You’ve started to incorporate more visuals into your work over the years. Now, Monolake will only play at places where there can be visuals and surround sound and things like that. I was wondering if the incorporation of the visuals came with more articulation in the music at the same time, because I listen to your sounds now and I can hear pieces of metal dropping with a decay as opposed to earlier Monolake releases which were like a field recording with a kick drum. Both awesome, but very different.

Robert Henke: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, for my visual explorations, there are numerous explanations. As far as Monolake is concerned, it really also came from a very pragmatic marketing perspective. Simply the fact that, if you have reached a certain level, people expect some kind of show. And I’ve found that a person behind a laptop is just not very interesting, especially at a larger venue. At some point, I just thought that it was a good idea to add a visual component. Also, because [of] the usual framework of where I’m booked, a lot of people also have a visual situation going on, the last thing I want to have is that someone [else] is making visuals. I had this in the past, ten or fifteen years ago, when Monolake was not in the position it is in now. It happened to me very often that I would play somewhere, at a festival, and some random assigned VJ did some stuff while I was playing, and a few times it was just completely horrible. I thought, this is completely working against my attention. So then you have two choices: either you insist on playing in darkness, like the Autechre solution, which is a very valid solution, I think — or you find someone or [have] some idea on how to incorporate video in some way. This is just the path that I followed the past three, four, five years as far as Monolake is concerned. And so far, it has paid off, because it has indeed provided another channel of attention, and it has helped put things on YouTube, etc. etc. From a very simple marketing perspective, it’s a very good thing to do — as well as being on stage, as a matter of fact. I performed Monolake in the center of the audience for a while, and I gave up because it worked so much against the expectations of the audience…

The other thing is that I always had an interest in art, and I always found visual art interesting and a topic worth exploration. It was just that I was too shy to make my own visual experiments public, because I didn’t consider them as “art” enough; it was just my hobby. I took photos since ages [ago], and I always enjoyed setting up lights in areas of parties, and I was always very aware of visual environments. But I guess I just never felt a strong enough urge to explore this on a more serious level. This just changed during the course of the last five years, more or less by accident. I got asked to do a sound installation in a situation where I felt that sound was inappropriate. And I thought, why not do a video installation instead? And this just worked out very well. One comes to another, and suddenly I had a bigger video installation going on – like a really big one, for my position in this whole art world, not art world – and from there, things just developed.

LIVE PERFORMANCE VIDEO OF MONOLAKE WITH THEIR AUDIO-VISUAL SETUP

Troy Micheau: I really see — especially in more experimental and electronic forms of music — that video and audio are very necessary for each other. It’s very rare to go see anybody anymore without some sort of visual things. The band I perform in — we have visuals and stuff — and to me, I can’t imagine not having it. I’m interested in where this movement is going in the next ten, fifteen, twenty years, especially if we can buy albums that we could be watching on our iPads and things like that.

Robert Henke: Exactly. There’s also, product-wise, everything ready to be delivered with visual content. The CD is dying; instead you have something on your iPad — so why not have something on your iPad that’s a movie too? It’s just a normal part of music as delivered. See YouTube; people go on YouTube because they listen to music. What happens is you go on YouTube and you see a random photo someone took. If you have good luck, it’s the cover of the album; if you have bad luck, it’s something. Then it’s better if the video content which is running there has a useful connection to music. So yeah, I guess that’s where it’s going.

“There is still all kinds of software with too many steps necessary to achieve things, simply because a lot of concepts still come from an engineering perspective and come from a tradition.” – Robert Henke

Engineering Works

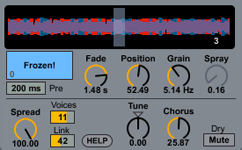

Max 4 Live Devices

Henke’s collection of Max 4 Live devices for public use.

Granulator

A granular synthesizer made in Max 4 Live.

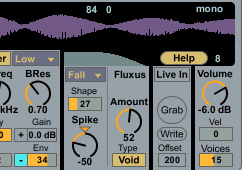

Ableton Live

Henke’s recounting of his involvement in creating the electronic music software.

Monodeck II

Henke’s first self-crafted MIDI controller.

On Digital Audio Workstations, Hardware, and Software

Troy Micheau: As someone who has been a part of developing a DAW (digital audio workstation) for the world, where do you see those things moving? For example, when I use recording software, sometimes it feels limiting to me, because I have to interface using a mouse or a mousepad, whereas something that I could actually be inside of or actually be using my hands to sculpt or have speakers around me and have it be more of an environment that reflects the [6-channel surround sound] show you did last night, seems more ideal. Have you given any thought to where you would like to see software move in the future?

Robert Henke: There’s tons of answers here. But a few things I find quite obvious are that there is still all kinds of software with too many steps necessary to achieve things, simply because a lot of concepts still come from an engineering perspective and come from a tradition. Audio workstations came from the tradition of tape machines, and tape machines came from the tradition from… what? Good question. But just the record button, the play button, the transport – those are all very old concepts, and they’re not really musical concepts. They’re concepts derived from a technical necessity. I could certainly see that at some point in the future, there will be evolutions of this concept which just work on a very different paradigm. For instance, who says that you need to press record? Assuming that memory [will] cost nothing, maybe you are recording, always. You have something like the Time Machine on the Mac – just in your music software! So you just play. You change things, and you don’t need to save; you don’t need to think about anything. You just say, “Hey, let’s go back to what I did at 2013, on my birthday, at 3 o’clock in the afternoon. Let’s see if this was good. Let’s copy a part of this into my current project.” I can’t see why this won’t be possible, especially if you look at, for instance, where MacOS is heading. Those things are getting very step-by- step incorporated into the operating systems. The time of the save button is something that will vanish at some point because [it won’t be] necessary anymore. So a lot of constraints will probably fall. Or playing according to a click. Software will be smart enough to imply what it means if you play a groove. And maybe you need to set one marker afterwards to refine it, but you will never, ever need to play something against a click anymore. That’s a strong belief of mine. The machine will be smart enough to figure out what you mean.

Troy Micheau: That would definitely be awesome. Before I made electronic things, I was a drummer, so I learned for many years to learn to play to a click, and it’s just the most obnoxious thing to have to play music while this thing is in your ear.

Robert Henke: Of course! Especially because you’re completely losing your own sense of swing, because you always need to concentrate, [to be] in sync with this thing, instead of following your own rhythm. So that’s one thing. The other thing is that we can expect the computer, as a classical box, will vanish. Like the iPhone, iPad — those are so much more the current modus operandi. The mouse and keyboard will probably, for a lot of things, disappear. I can see a lot of implications for music software there, too. How do you create music on a touch-screen surface? Let’s imagine that in a few years from now, a touch-screen surface will have tactile feedback so it’s not just a glass plate. If there are faders on this thing, you can touch them; you can feel them moving. You can actually create all kinds of surface which feel natural. If there’s something like a guitar body displayed on the screen, you go over it and you feel the screens. You can maybe even feel them vibrating and stuff like that. There will be a lot more virtual concepts which don’t feel virtual anymore. Just how we are used to now – it’s completely normal that we can look at a street map and the street map is adapting to where we are. This doesn’t feel artificial to us anymore. We don’t perceive it as magic or strange; it’s just how it is. Or we can look from above down on earth. So I believe there’s a lot of those little things coming which will change the way music software will behave. They will all be changes which will go very slowly; nothing will very rapidly move but step-by-step, old ideas will vanish and that’s what will come. Or I could imagine that this whole thinking of a track will also be a thing of the past at some point. Because a track is just a container; a track itself is not musical. Especially not a midi track for instruments. Having empty tracks – you could imagine something as a user interface that doesn’t deal with tracks at all anymore; which, the way the software looks is the score. So there’s just the score. Part of the score is that you have a synthesizer in there. There’s many, many things I can imagine in there.

Troy Micheau: That’s awesome; you just hit all of my little points in there, especially the touch-screen.

Robert Henke: Currently, the touch-screen is totally annoying. I have all these iPad applications and I tried them all out for making music, and you see I have my little fader box, and I love it because it’s tactile feedback; it’s so much nicer than touching a glass plate. For the Monolake shows, I use an iPad, but I also use two of these [other] things. And I will probably get another iPad so I have more functions available at all times. But really critical stuff, which I actually play, doesn’t work so well on the iPad.

Ω

thanks for sharing this, it was a real treat to have henke come to impart his knowledge, and share his sound with us.

[…] of electronic music at Stanford University and performing live across the US. Here’s a great interview with Henke and more of his […]

[…] of electronic music at Stanford University and performing live across the US. Here’s a great interview with Henke and more of his […]