Artist Simon Benjamin (center) with Berette S. Macaulay of Black Cinema Collective (left) and Elisheba Johnson of Wa Na Wari (right); photo courtesy of Berette S Macaulay; photo by Olivette Henry

For two weeks in April, Benjamin presented his latest exhibition, A Bolt from the Blue, at Jacob Lawrence Gallery on the University of Washington campus. Additionally, Benjamin participated in an artist residency and a series of off-campus programs, including the Sunday Dinner film screening at Wa Na Nari.

Based in New York but originally from Jamaica, Benjamin uses his Caribbean origins to explore how “lesser-known histories and colonial legacies impact our present and contribute to an interconnected future.” In Benjamin’s films, water serves an important function — both as character and environment, detailing its effect on labor and daily life in the Caribbean.

Entering Wa Na Nari, I was immediately greeted with smiles and open arms. Before the screening started, the Wa Na Wari co-founder Elisheba Johnson and Jacob Lawrence Gallery Legacy Residency Program curator Berette S Macaulay announced that there would be food available for all the guests to enjoy. Prepared wonderfully by Taste of the Caribbean, an array of savory Caribbean cuisine featured grilled chicken, peas and rice, and pot pies, along with my personal favorite: oxtails with rice. The rich delicacies conveyed Wa Na Nari’s efforts to build and support the community.

After Johnson thanked all the collaborators who made this event possible and the audience for attending, she introduced Simon Benjamin. At that moment, I learned that the man who I had been slightly conversing with was the artist himself! His presence among the crowd added the feeling of a home gathering of friends and family — as opposed to an attendee at an event with a bunch of strangers.

Film stills courtesy of Simon Benjamin

Two Score Full Moon (2019) – 1:52 runtime

For the entirety of its runtime, Two Score Full Moon displays the image of a hand submerging in a body of water. We see the hand interact with the water by splashing around and creating waves, getting more comfortable in its environment the longer it is there.

Simple as it was, Two Score Full Moon was my personal favorite out of all the films in the showcase. During the event’s intermission, Benjamin revealed that his films express the contested relationship most Jamaicans have with the sea, due to their inability to swim. A few audience members then opened up about their own relationship with water; one person even recounted a traumatic memory of almost drowning as a youth.

The Memory Held Within (2022) – 6:55 runtime

The Memory Held Within was the first film of the evening to introduce a split-frame technique that Benjamin utilizes in many of his films. On the left side is a screen engulfed in blue that contains subtitles; the right side depicts moving images in black and white. We first lay our eyes on a hand putting sea shells and stones on a flat surface resembling a table, displayed synchronously with the subtitle, “my whole family was born in this neighborhood.”

The image then changes abruptly to a man — presumably the narrator — who stares directly into the camera. As he confronts us, the subtitles are left blank. The image of a forest follows, with the camera running down a vine; subtitles appear once again to describe the living conditions: “there isn’t always power these days as the state doesn’t turn it on too often.” The final image shows an empty swimming pool with a giant boulder in the center and the haunting phrase, “there is also very little water.”

The entire film could be seen as a metaphor about Benjamin’s ancestral ties to his homeland, with its changing environment due to resources vanishing from colonialism and extraction.

On Childhood (2019) – 1:52 runtime

For the entirety of On Childhood, a man peels an orange against a black screen, in a way that might seem unorthodox to Westerners. He also speaks for the duration of the film, but there are no subtitles to translate what he is saying. According to Benjamin, the method the man used to peel the orange was an homage to Jamaica — offering a fascinating insight into how subtle societal and cultural differences can inform a person’s identity and sense of belonging.

Wa Na Wari audience; photo by Berette S Macaulay

For the first three films, the audience was seated in rows, like in a traditional theater. When On Childhood finished, there was an intermission; Johnson told the audience that she wanted us to move our chairs and form a circle, so we could see one another and be in conversation.

Benjamin opened up the space and shared his motivations for making the films, divulging the contentious relationship many Jamaicans have with the sea. Due to a lack of access to safe swimming spaces, most Jamaicans are unable to swim. Yet despite that, many still depend on the sea for their livelihoods. Sea labor is extremely dangerous, and in Jamaica, many fishermen risk their lives to perform their jobs. This notion was the focus of the next film Errantry, in which Benjamin wanted exposed the realities of sea labor in contrast to the romanization of it.

Errantry (2021) – 11:00 runtime

Following fisherman Tommy Wong out at sea on his boat, Errantry also utilizes split-screen framing, but unlike The Memory Held Within Water, does not have subtitles. Benjamin said he decided against using them because he wanted to portray the universality of the character, in hopes that the audience could identify with him, even without understanding what he was saying. It was a powerful omission.

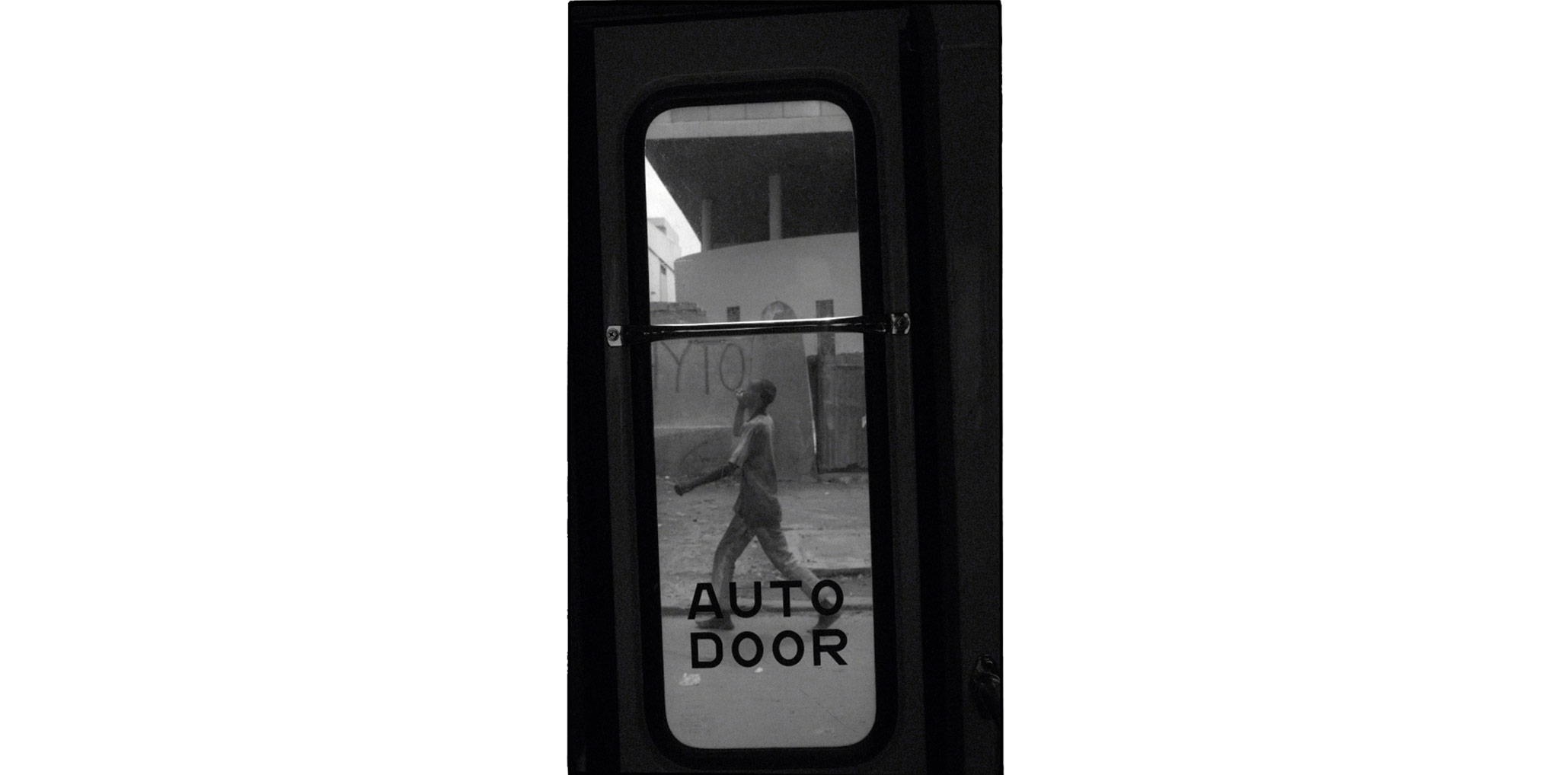

Auto Door (2020) – 3:00 runtime

In Auto Door, Benjamin transports audiences directly to the landscape of an undisclosed island somewhere in the Caribbean. Here, we go on a journey to meet the residents of this land as they talk about their home, which they lovingly refer to as their “neighborhood.” Benjamin employs a new framing technique in Auto Door; the entire screen is filled with a colored picture of two jukeboxes leaning against a white wall — but superimposing it is a small TV inside of a crate, which displays a moving image in black & white. This framing effectively engages the audience to interact and listen to the film subjects regarding the ways colonialism has forever altered their homes and the environment they depend on.

Stills from A Bolt from the Blue installation at Jacob Lawrence Gallery; installation photos by Leo Carmona.

Ω