Probably not for you, if the moon is really your thing.

By Jacob Lynch.

In 1989, the American photographer Andres Serrano exhibited a photo in North Carolina of a crucifix submerged in a glass of the artist’s own urine. People got mad. It was called Piss Christ; can you imagine how mad people got?

But Andres Serrano never made people furious enough that riot police had to be called to one of his shows. The Impressionists did. In Paris in the 1860s and 1870s, the people were mighty riled by The Impressionists. They were crazy mad. Not ‘writing a letter to the newspaper’ mad, but ‘ripping up the pavement’ mad.

Why?

Well, looking back from this day and age it doesn’t make a lot of sense. But at the time, the art world was insulted by The Impressionists’ practice of copying the works of Spanish masters like El Greco and Goya, but in their own style. Their style happened to be less concerned with realistic depiction and firm lines than with the essence of the subject and its impression on the new artist. At a time when the photographic image was challenging oils and canvas as a medium for reproduction, The Impressionists realized a new direction for painting. What Claude Monet, Edouard Manet, Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and their followers were seeking in their paintings was more than what you could see, but what you could feel. They were after the ecstatic truth.

They did this by finding a way to give greater energy to light and movement, as it appeared on a flat surface. The trademarks of the style are short brushstrokes through unmixed blobs of color and the depiction of scenes of the everyday outdoors. But for every Impressionist hallmark, there is another that rejects it –- they weren’t a very cohesive bunch –- so laying down hard and fast definitions of what The Impressionists were is always going to miss a lot of points. Probably the one thing that truly connects the majority of them is The Louvre. This is where in the 1850s and ’60s Manet and crew would set up their easels and stare into the great works for inspiration. In love with the composition and story-telling of these classic paintings, like any young art student of the time, they wanted to pay homage. But rather than just copy, they wanted to better represent the way the painting made them feel. They wanted to express their impressions.

There are two approaches to standing in front of a wall and looking at the painting that hangs there. One is the, “I don’t know much about art but I know what I like,” school, appropriated by the majority of the general public. The other is the act of seeing coupled with that of knowing. That is, seeing the piece of canvas in front of you and judging it not on its immediate appearance but on its appearance and things like its historical relevance, its predecessors, its legacy, the fate of its critics, the fate of its supporters, what was written about it at the time, what was written about it since, the success of other artists who said it was relevant to them in the future, what was written about them, and what was going on in that particular country and that particular time.

For example, Pablo Picasso’s Guernica is an amazing picture to look at if you know little about Picasso or European history. But the real power of the mural comes out when you understand what he was saying about the Civil War in Spain, the Nazi’s, fascism, and the terrible slide of Europe and Asia into bloodlust and destruction.

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica

On the other hand, Girl in a Chemise, from the same artist, is like looking at the moon. You need bring nothing to the experience of seeing to be astonished by it. It matters not what you know about the Blue Period and his models, or Spain or France or history, to be knocked asunder by the beauty and solemnity of the thing.

Pablo Picasso’s Girl in a Chemise

As for the Inspiring Impressionism exhibit at the Seattle Art Museum, I knew we were in trouble when the co-curator of the show, Ann Dumas, said, “It’s much more complex than it appears on the surface.” For those of us there to appreciate the paintings for how they look, that’s not good news. I imagine one would want the story of the thing to appear on the surface. They are, after all, paintings.

But the new exhibit at the SAM is hard work. Of the two ways of appreciating paintings, there is little of the first, and much of the latter. Impressionism is a style that, by definition, exists in relation to other works. This show gives the feeling that one needs to go searching for the payoff in the 700 section of the Seattle Public Library, or in the text, the time lines, and critical explanations provided by the gallery. Though Ms Dumas has said she would rather avoid the term art ‘lesson’ when referring to the show, an art lesson is what she has provided, for better or worse. On the positive side, the side by side comparison of The Impressionist works and their predecessors is unique and very effective. And some of these pieces are remarkable in their own right. On the downside, it is likely to confirm in the minds of much of the general public — myself included — that a trip to the gallery (or museum, in this case) is sometimes about as fun as algebra is. I have often wondered why the Seattle Art Museum is called a ‘Museum,’ when so many of its prestigious counterparts around the world prefer the term ‘Gallery.’ Inspiring Impressionism is clearly a museum exhibit — one about history and learning, rather than the purely visceral experience of seeing beautiful thing on walls. That will suit who it suits. Me? I wanna howl at the moon.

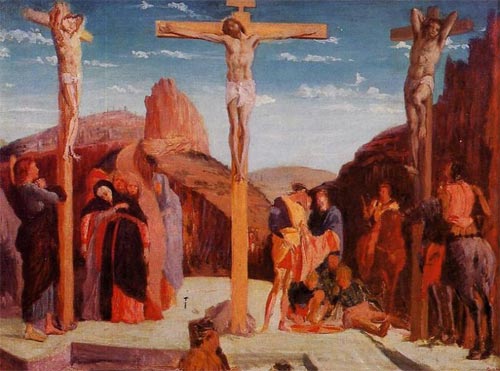

There are, however, a few visually arresting pieces. And these alone more than make the show worth the $20 of admission, for they are true classics. From the entrance though, the exhibit takes a while to warm up. Cezanne, Degas and their contemporaries made plenty of mistakes on their way to the perfection of a new style of painting. Unfortunately for them, due to their subsequent fame, these mistakes are now on public display as artifacts of art history, when perhaps they shouldn’t be. In Degas’ 1861 painting, Crucifixion, it is difficult to see the ecstatic effect of light and energy that the Impressionists were seeking, and easier to understand the early criticism of their works as childish copies that didn’t improve on the original. Nearby, though, is a tiny gem; the same artist’s studies after Two Italian Madonnas, just sketches, have the touch of a future genius, and a serene smile which rivals that of the very famous Mona Lisa. And although he is only there to offer comparison, the large landscapes of Claude Lorrain have a drama in them that is as compelling as the best works of painters of the American landscape Asher Durand, Albert Bierstadt, and Thomas Cole. Still, in this first room, I heard a lot of people pretending to be impressed, feigning admiration, as is de rigeur.

Edgar Degas’ The Crucifixion

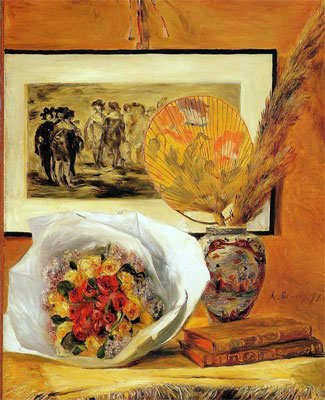

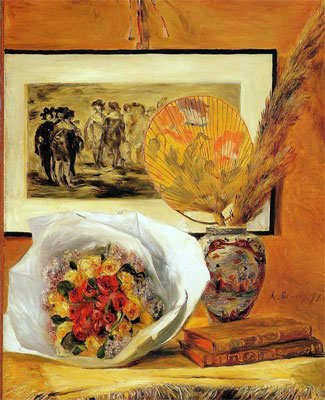

The worst thing in this room is Renoir’s 1871 Still Life with Bouquet. A patchy homage to his artistic influences and the work of his contemporaries, it is essentially a little artsy in-joke, art about other art, about other art. It was here that I thought of Vonnegut’s comments about literature and disappearing, and figured maybe he was talking about this place. Maybe it was the artist co-op audio commentary, or maybe just the stale tang of the hoity-toity previews I read, but there was something about this show that made me think SAM were very interested in appealing to the art critics and historians (who are perhaps .06% of the population) and not that concerned with the rest of us, who perhaps don’t know too much about art but are keen to give it a go.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Still Life With Bouquet

When the Impressionists figured it out, into the 1870s, beautiful things were done. When I saw The Zuiderkerk at Amsterdam, by Monet, I actually had an involuntary physical reaction; I smiled, almost laughed out loud before I caught it in my hand. The painting lit me up, like Monet had lit up the Groenburgwal canal, and all of a sudden, it was clear what these artists had been trying to do for the past 10 years. The classic Impressionist hallmarks were all there – the brush strokes, short and energetic, and the smeared blobs of unmixed colors, the scene of the city outdoors. But what fizzed inside me so was the optimism of the painter, the presentation of such a sheer, genuine belief that the deeper truth of the view is really that beautiful. It is the optimism of new lovers and maybe too it is associated with youth and naivety, except that it has been so expertly rendered.

Claude Monet’s The Zuiderkerk at Amsterdam

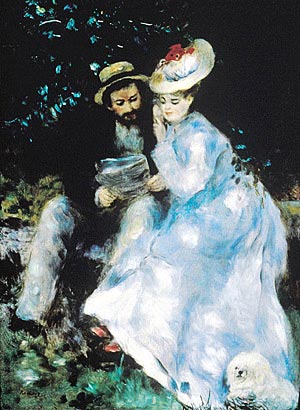

From that painting onward, moments like these were more regular, with Monet, Renoir and Pissarro hitting more frequently than the others. The ’70s were good for Monet, as he produced a number of works which effectively demonstrated how these new Impressionist paintings could make people feel things that other paintings couldn’t, notably Autumn on the Seine and Summer. The Renoir pieces, Confidences, A Bather, and Mother and Child further massage the inner workings to stimulate an ecstatic truth, making much more of the subjects than I would have thought possible. Why would I feel sentimental for some guy and some woman flirting around in some garden? Because I realized that the electric, luminous light of the woman’s dress is not how it would look to a camera but how it would look to that man, years later. That is how the dress would glow as he remembered that day and that woman and how beautiful it all was. It is the light of memory, the truth of the moment as an experience rather than a document.

Pierre-August Renoir’s Confidences

In these rooms, it was in ignorance that I found the bliss. Or, rather than demean those ignorant ones like me, it was in realizing what it wasn’t important to know, and jettisoning the junk and intellectual baggage that threatens to obscure the light source is important. Horses for courses, though, and college students and trainspotters will be thankful for the wealth of words and the towering history lessons. As a museum piece, the lines of chronology are firmly drawn at the SAM.

Though the rooms of ‘Inspiring Impressionism’ are pock-marked with sumps, there are also dry and solid places of high ground, where the light is so brilliant that you catch the laughter in your hand, and understand how our memories romanticize what has actually gone before.