A Meandering Path: Anyone Can Be Anything

As a young person in Kansas, johnson had long set his sights on becoming a medic in the military. Yet life threw him an unexpected curveball when it came time to enter the Navy; his vision, it seemed, was too poor for him to ever see active duty. So he switched gears. Setting down his previous dreams, he began seeking relocation “as far away from Kansas as possible.” That place was soon identified as Seattle — and though the reason for his impulse was hazy at the time, johnson eventually learned that following his intuition would lead to a fortuitous series of circumstances. A job opening landed him an Americorps position working for a community-serving nonprofit, and from there, he took on a brief career stint in tech and data analytics. It was in that role that johnson discovered his love for drawing — a perfect reprieve for what was otherwise a stressful day-in, day-out sludge of mathematics.

Working in Seattle’s tech industry allowed johnson some rare opportunities. His small-scale personal drawings eventually led him to creating corporate murals for in-house clients — and slowly, he moved onto larger and larger projects, until one day, he came to a realization.

“Being in consulting, I was like: I already know how to talk to people and pitch clients [and] get opportunities, so I feel like I should be doing this for myself,” recalls johnson. “And I want to be doing more work that was representative of Black people… so I quit and started doing art, and that’s kind of what got me doing what I’m doing right now.”

“It’s kind of nuts how it all came together,” he adds, somewhat to himself.

johnson has learned to forge his way by way of his own meandering path, and that can be found in everything, or anything — from the time that he dabbled in stand-up comedy to the sustainable architecture he is now studying; from the philosophies under which he thrives to the day-to-day materials he uses. While the formally-trained painter might use acrylic or oil paint in his works, johnson’s large-scale paintings defer to construction materials and house paint from Home Depot. The decision is not only wildly cost-effective, but also provides johnson with the layering capabilities that resonate with his particular approach to the craft. Not being taught more “traditional” ways of artmaking has allowed johnson to embrace the “anything is anything” philosophy more fully when it comes to the mediums he uses.

Which isn’t to say that putting a banana on a wall — as with Maurizio Cattelan’s $120,000 banana at Art Basel — is something that johnson would ever interpret as valid for his own artistic practice. But it does mean a level of experimentation that might not be accepted as conventional or comfortable in traditional arts institutions, even when johnson’s works may be ostensibly clad in a friendly package.

“I was talking to a reporter recently… and they’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, [your paintings are] all nice and colorful,'” says johnson, “and I was like, ‘That’s not the intention. That’s just color. That’s just a narrative that I’m giving it back to you in,’ but you’ll never find a picture that I’ve made with a person smiling.”

Indeed, to see johnson’s work as simply “nice” due to their bright and rich color palettes would be doing him and his work a vast disservice. It would be to completely erase and misunderstand his intentions.

“The creation of the work is always heavy, because I am a person that wants to know what’s happening, and I want to reflect that back in the way that it happens,” johnson says. “I don’t ever want to sit there and say, ‘Here’s beautiful pictures.'”

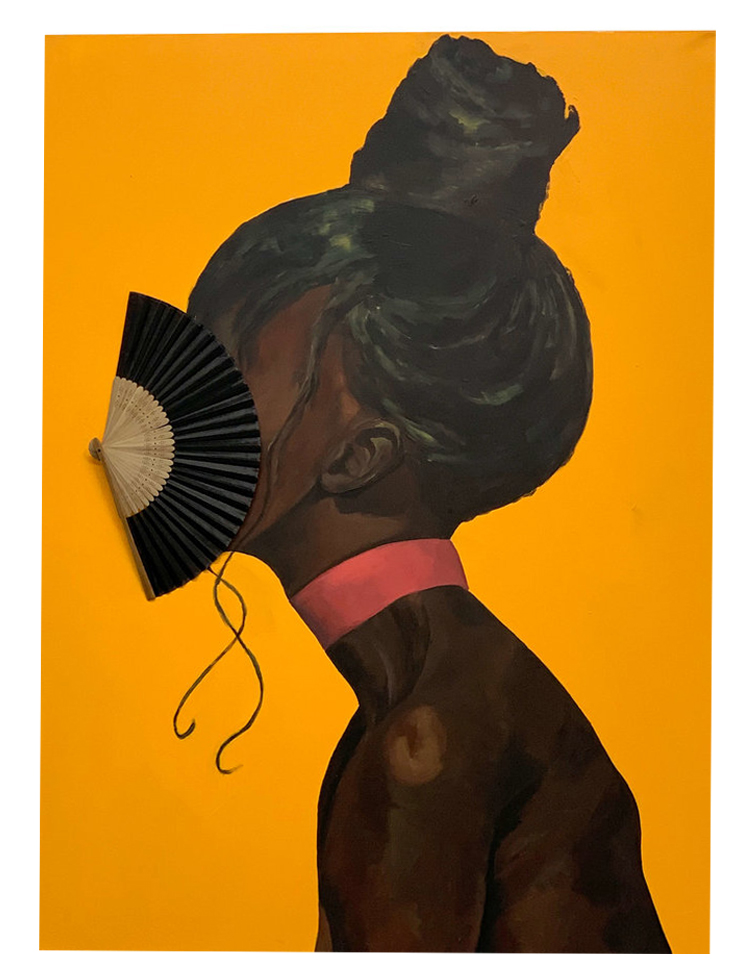

Generally based off of real-life friends and acquaintances, johnson’s subjects never smile — not because they are stoic, or that johnson himself is stoic; far from it, in fact. johnson simply intends their likeness to be a social and political commentary on being Black in American society.

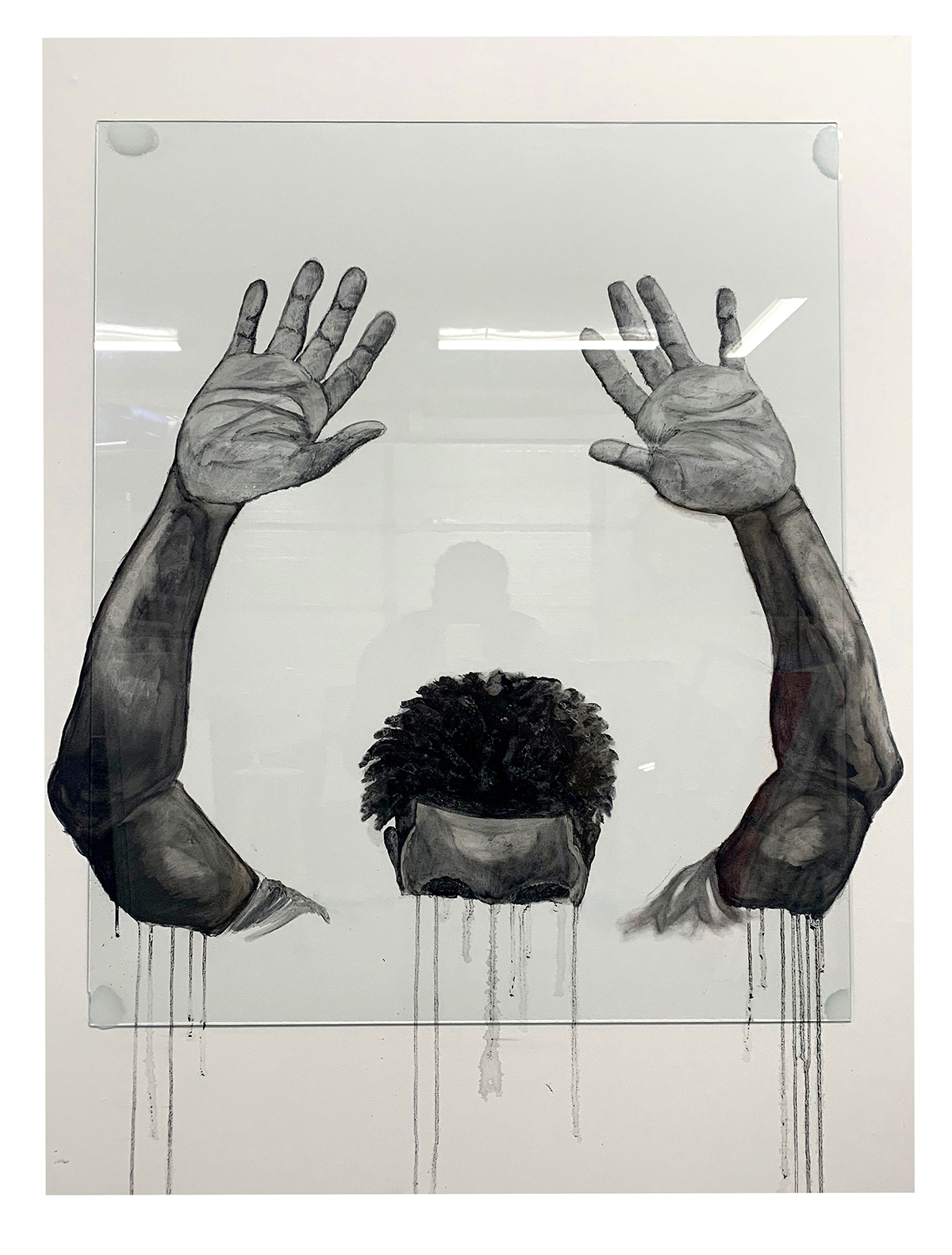

“There’s a reason you can go through and you can see all these Black and Brown men and women and people that are nonbinary that will have their faces covered up,” explains johnson, “because again: these are times that we just have been trying to progress, and things have been taken from us.”

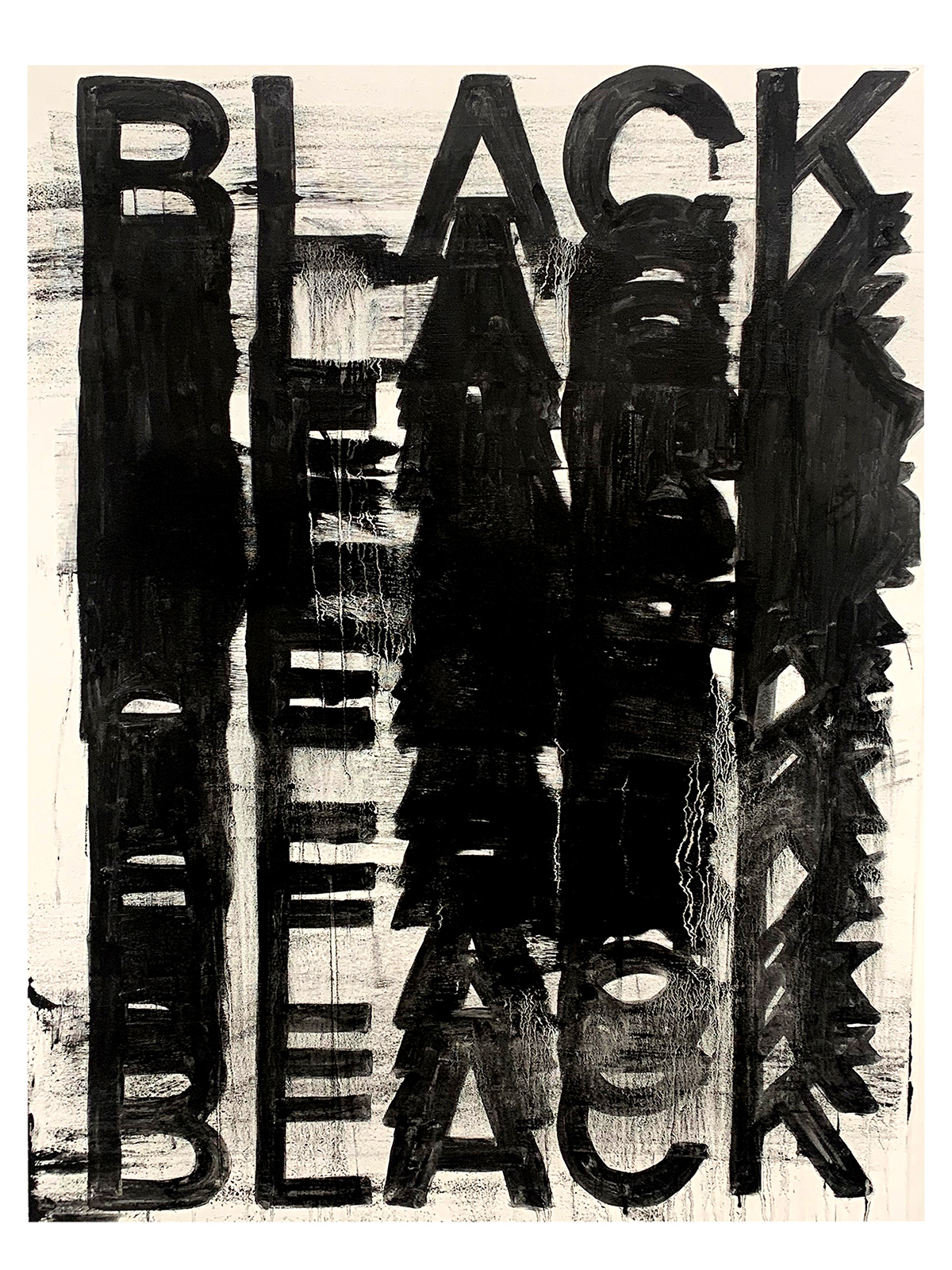

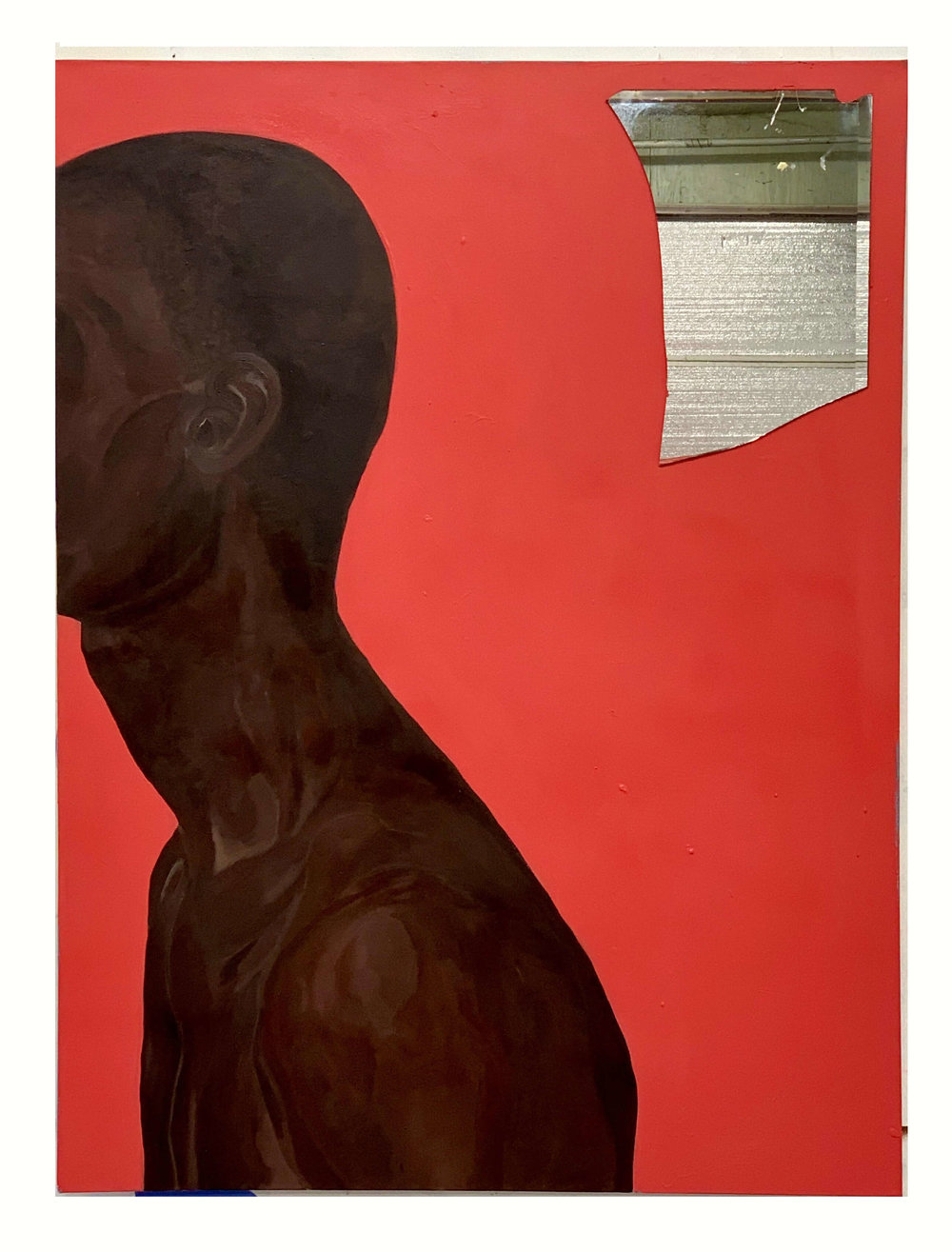

Some of johnson’s more emotionally-involved pieces intentionally incorporate iron oxide, a naturally disintegrating material that operates in greys and blacks, as a counterpoint to his more colorful pieces.

“I like the fact that whenever I put iron on a canvas, that, with 100% certainty, it is going to fall off of a canvas over time,” he says. “I always do images of Black commentary with iron oxide, because over a certain 50, 70 years, that painting self-destructs by itself. You know that once you get that, it’s inevitably all going to fall down, and hopefully, by the time everything’s falling off that painting, we won’t be dealing with the same problems that we’re dealing with around race right now.”

This perspective may come off as bleak upon first blush, but there is in fact a bit of hope embedded throughout it, because these works are intended to be informative. johnson is the son of a father who was part of the Little Rock Nine — a group of nine Black students who were among the first to integrate in Arkansas — and as a father, he speaks often and candidly with his young daughter about race and being Black in America.

“Coming from the Midwest and the South, I’ve experienced racism since I can remember integrating with kids, and I remember thinking when I was her age that there’s no way people are going to be talking about color for another five years,” says johnson. “And then, I got eleven, and I was like: there’s no way by the time that I get done with high school people will still talk about race. By the time I got done with high school, I was like, it might be my kid before we start talking about the end of race, and now… she’s six, and I’m like, well, maybe it will be her child before shit’s really not a thing about color anymore. But it is, so we just kind of have to arm everyone with the information that we have.”

For johnson, the 2020 wave of Black Lives Matter protests has embedded within American society an entirely different kind of energy. Work has picked up significantly for him and his artistic peers, though he approaches it with a level of cautious optimism regardless.

“This time, I swear to you, feels now different than any other time,” he says. “Who knows how all of this will play out… I’m just making work about topics and things that I always have. This is us, our lives, collective moments and realities. You may have never seen it prior, so buckle up and fucking chill. Shit’s about to get incredibly real.”

The Unauthorized Biography of a Black Man

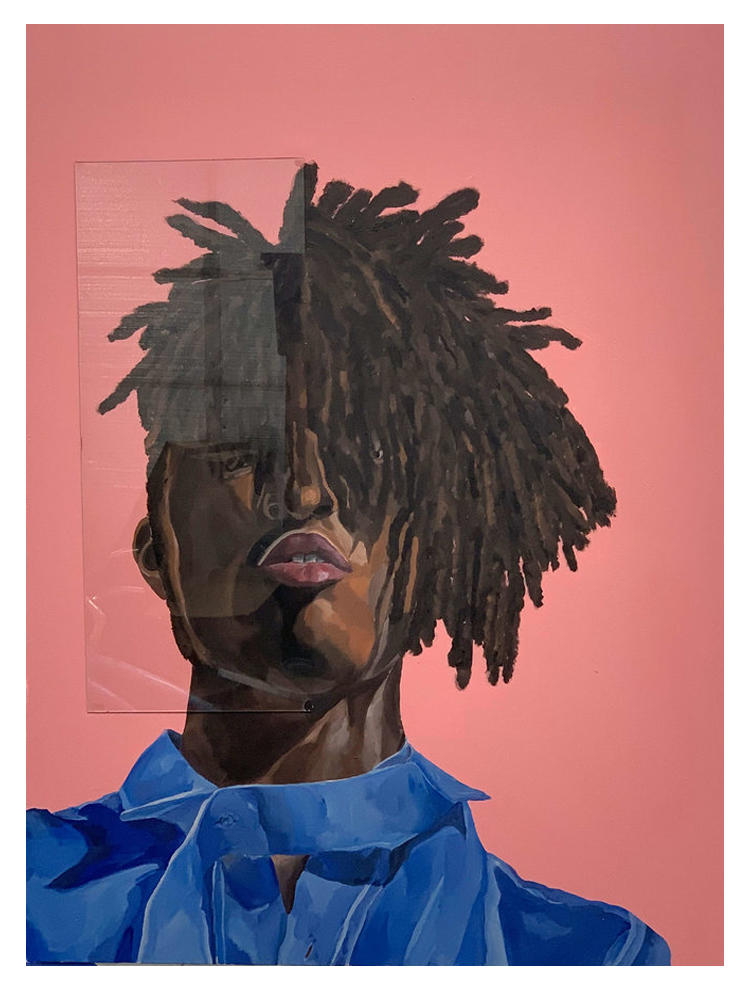

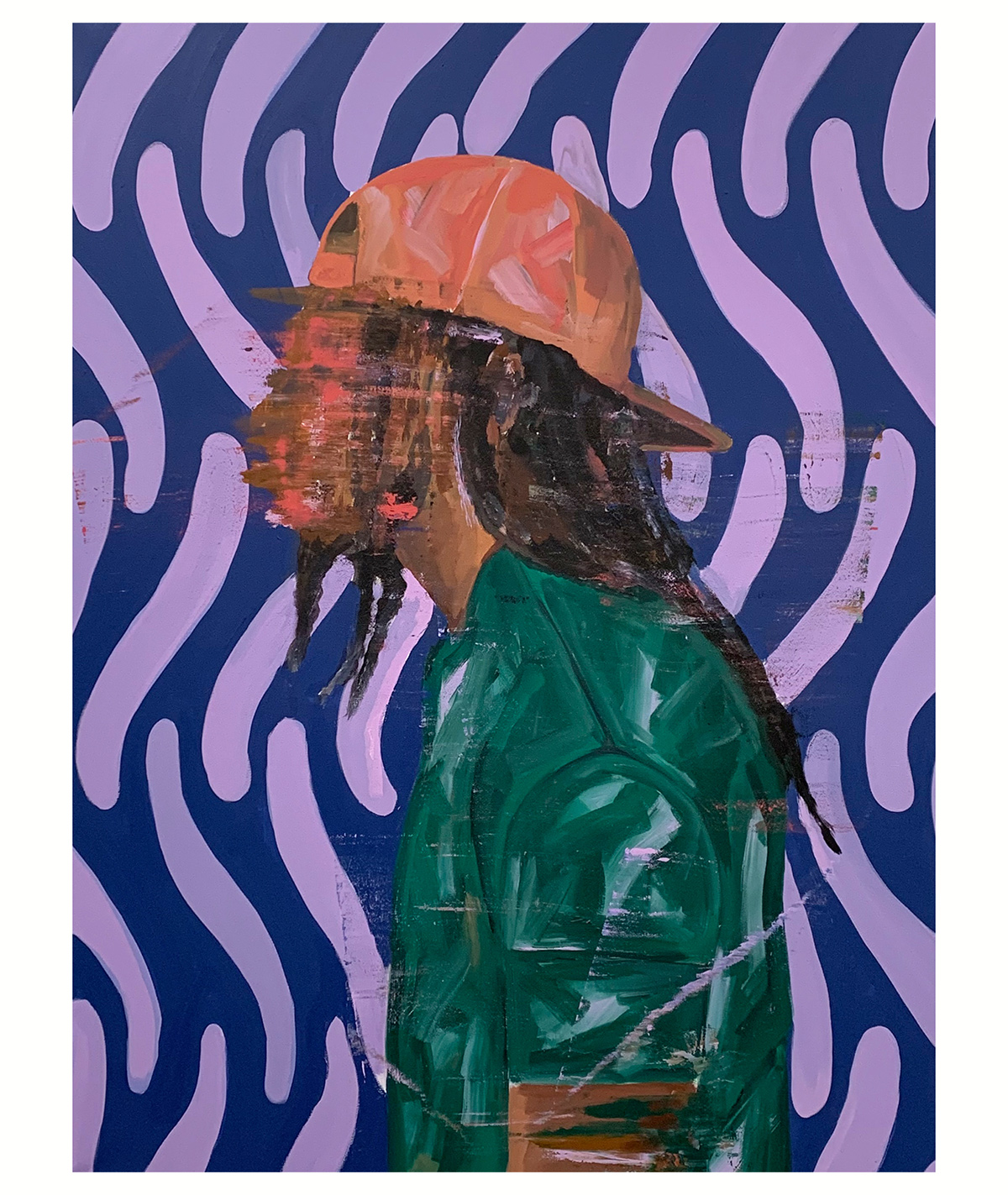

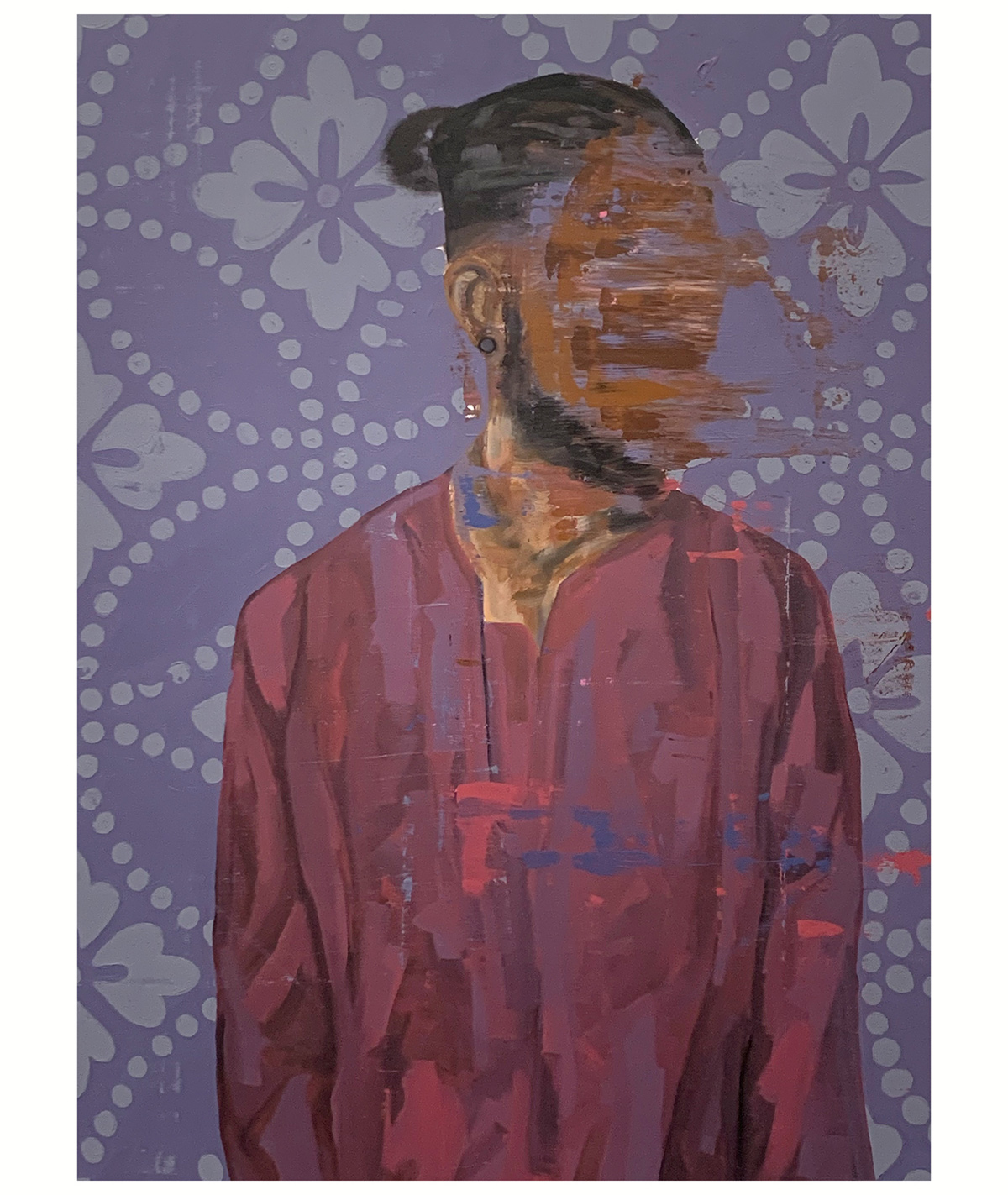

For nearly the past four years, johnson has been working on an ever-evolving mixed media portrait series entitled, “Being Human,” which features Black and Brown people with their images frequently covered up or distorted. The series iterates slightly every year, building atop similar themes but adapting slightly to the latest oppressive actions dished out by America society.

2017’s portraits, for instance, featured patterned backgrounds set within sharp shapes and Black faces in profile view, often cropped off the edge of the painting. December of that year marked johnson’s first time receiving major press coverage in a local publication, via

“Now, it’s got to the point where all the faces are just smeared altogether, and it really has to deal with the idea that Black and Brown people have our history covered up or distorted to fit another part of this narrative,” says johnson.

He goes on to cite a 2015 incident with McGraw Hill — one of the biggest publishers of school textbooks, who had written in a World Geography textbook African slaves had migrated to the country in the 1600s as “immigrants” and “workers,” thus whitewashing and erasing the painful legacy of slavery.

“Shit like that is the reason why all these images were getting made…” says johnson. “Our story is just continuing to be covered up and distorted.”

johnson’s 2020 iteration features faces that are distorted and blurred out as its main recurring theme. The process is intense, personal, and emotional — beginning with a fully-formed image of a Black person, which johnson then deconstructs through a process of removal.

“It’s funny because everyone that’s watching me paint is like, ‘Okay, so you just went through and painted an entire face and a background, and once you’ve got this whole piece, now you’re going in and destroying it,'” says johnson. “And I’m like, ‘Yeah, that’s culture. That’s us. That’s what’s going to end up happening to us’ — so it’s very important that I’m not just trying to make picture-perfect portraits of people that look like me, and that I’m actually telling the real story.”

One of johnson’s latest pieces, a temporary large-scale horizontal mural entitled “The Unauthorized Biography of a Black Man,” is located at Two Union Square in Downtown Seattle and features Seattle dancer and choreographer David Rue as its main subject. Rue, portrayed with eyes closed, is replicated across eight different frames which show a progression of Rue’s face being gradually deconstructed. Jonson ends the piece with a quote by James Baldwin, which says, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

“This piece was by far [one of] the hardest pieces to make,” explains johnson. “I know [David Rue] very, very well and to paint and destroy them was hard. Like, very hard. Especially on the scale that it was.”

Likewise, through the 45 hours that johnson worked on the piece, he had much to face head-on himself, experiencing a spectrum of difficult emotions associated with his own experience as a Black artist working in a public space and dealing with on-site harassment, as well as the impacts of what it means to create such highly visible work about other Black individuals.

“I went through that, ‘Oh, people were here then gone’ phase, the “what if someone doesn’t like this and kills me while painting it’ [phase], and so much more,” johnson describes. “It really fucking hurt. More than anything, knowing that this image is here, then gone, is the reality of so, so many Black men at the hands of senseless violence.”

Yet while johnson’s intention is for “The Unauthorized Biography of a Black Man” to be a symbol of deconstruction, he acknowledges that some viewers may experience it as reconstruction if they approach it from an opposite direction. johnson likens this dualistic nature to Kendrick Lamar’s 2017 album, DAMN., which was sequenced in one direction but designed to be played backwards — each rendition vastly different in mood, but just as laden with embedded significance.

Intentional Pathways Towards Change

Though johnson may stand out as a shining example of a self-taught artist finding his true voice and place in the local art community, johnson’s story may in fact be one that is nothing new. Artists of color, often neglected by mainstream arts organizations and institutions until it becomes fashionable to support them, often have to duck and weave to forge their own sustainable pathways. Though the 2020 Black Lives Matter moment has led to more artistic opportunities for johnson, the structures and mechanisms through which one supports and engages Black artists is still flawed, and changing these systems is extremely important to johnson.

Immediately following the death of George Floyd, johnson, like many other Black artists, saw an uptick on social media of strangers grabbing his artwork and re-posting it. johnson intervened. Though it was uncomfortable, he contacted many of those strangers personally to suggest additional steps they could take to help the cause, stressing that the moment was not specifically about him — barry johnson, the artist — but about Black lives as a whole.

“This isn’t about my art or me in this moment,” he explains. “My art has always been about us — so do not, in this moment, take time to put a magnifying glass on me.”

By giving these individuals a moment of his time, johnson shared the ways in which he, as a Black man, needed to feel supported rather than feeling like a token. The conversations also illuminated that many of these individuals truly believed that they were showing solidarity, whereas johnson believes that true solidarity goes beyond such behaviors.

“Solidarity works by us all saying the same name of the people that were killed and then holding our government and our local legislation to the point where it’s like, you need to bring about change…” johnson says. “I think in this moment, it’s very important — for people that truly want to be a part of change — to just take a step back and observe, and look for a moment where they can be of assistance. Because whenever people just jump out there and do whatever the fuck they want to — because they want their voice to be heard and they feel like they’re doing the right thing — it actually ends up causing more problems to happen.”

“As a Black person, I can tell you this: we’re sitting here now, and we’re skeptical,” johnson goes on to say. “It doesn’t matter if it’s the largest protest that’s taking place in U.S. history; we’re still skeptical.”

To johnson’s point, simply reposting artwork by Black artists is not enough — and it is short-sighted and fleeting. Long-term change requires systemic change and sustained effort. In the past five years of his artistic career, johnson has had to adapt his expectations and standards for success; it was an eye-opening discovery to learn first-hand that the system had never been built for artists like him.

“I always thought that the way to do that as an artist was through people saying, ‘This person can make unique work and that their work is deserving of people buying it.’ I got rid of that idea very long ago,” johnson explains. Though there had been a short period of time when he had been shooting for accolades and public recognition through various Seattle arts publications and institutions, johnson was humbled after being hit by nearly two hundred rejections in one year. Luckily, his high school experience of working as a telemarketer had helped him grow a thick skin — and rather than feeling like he had something to prove, johnson instead concluded that mainstream institutions simply didn’t understand him or his work.

“By the time that they got it, I had given up on the idea of applying for grants and everything…” johnson explains. “Whenever an institution was like, ‘Oh, we don’t think you’re qualified for this,’ I’ve just always been like, ‘Cool, I’m just going to fund these things myself.’

In a world where mainstream arts institutions consistently struggle to find ways to pay artists equitably, johnson is an inspiring example of how the means will be present as long as one prioritizes them. johnson, who has worked across countless mediums and with a who’s who list of local collaborators, says he is most proud of his ability to collaborate with peers in a way that allows them artistic freedom as well as adequate compensation.

“I can come to them with a concept… and I pay them personally out of my own pocket,” explains johnson. And though he stresses that he is a Black kid from Kansas and not a person with massive degrees of wealth, johnson demonstrates that an equitable artistic and collaborative exchange is of the utmost importance to him.

“Anytime I post anyone with a project, I’ve got money to give you,” he explains. “Even if I paint them, if the painting sold, then I would give them 30% of anything the painting sold for. Just to even use their likeness.”

In 2019, johnson launched a self-funded grant called No Accidental Greats (NAG), which unites the whole region by being open to artists spanning from Seattle to Tacoma. The latest recipient was Stephanie Morales, who was given a cash grant of $3,000, along with free space through Alma Mater in Tacoma and BASE, an experimental art space in South Seattle. The concept, more than just giving artists money, was to “work with these different people to create the community to eventually, hopefully, create some sustainable pathways for them to be able to elevate their career as an artist.”

“I’ve always been a big proponent of ‘we,’ not ‘me,’ and I believe that’s how greatness happens,” says johnson, explaining the name of the grant. “Nobody is great by accident. It has to deal with a lot of work, and in most cases, some of the greatest people we’ve seen throughout history were a product of the group that were around them.”

Following the creation a highly-visible, large-scale Black Lives Matter” mural at Capitol Hill Occupied Protest in June 2020, johnson is now a part of the 16-member VividMatterCollective. Using their combined power, the group has given unexpected donations back to community members, as well as leveraged their influence to collaborate with the City of Seattle on permanently engraving the mural into the cement. Perhaps the most exciting part, though, is that one can assume that future actions are still to come.

Video Update w/ barry johnson

Note: This video update takes place after the initial interview which sparked the written text piece. It felt necessary as much had transpired between June 2020 and September 2020, including the Black Lives Matter mural created by VividMatterCollective at Capitol Hill Occupied Protest, and subsequent opportunities which have resulted from it.

Structural Change is Long Overdue

Likewise, johnson has been keeping his eyes open for the arts organizations that are doing more than simply highlighting Black artists they’ve supported in the past. Supporting an artist, he says, is not about saying the right words or giving a one-time grant and throwing money their way. It’s about finding ways to elevate them, long-term. Much like the fight in justice for Black lives, real solutions lie in long-term systemic change, both in the political system of laws and in the cultural system, as it relates to access and opportunity to and for the arts. Yet it can be exhausting. As someone who sees the benefit of investing time to direct message strangers on social media and educate them about reposting work by Black artists, johnson has also experienced plenty of frustrating experiences in his attempt to speak truth to arts organizations.

“I’ve talked til I have been fucking exhaused; til I have sent every fucking ounce of oxygen out trying to create change within people and organizations that ain’t seen nothing happen,” says johnson. “It was like, ‘Yo, I feel so fool right now. I’ve invested so much of my energy, and nothing’s happening.'”

While johnson has gained the bulk of his attention for being a painter, the inextricability of painting from mainstream art markets is one that johnson finds highly stressful. To be able to create art that is not simply just locked away behind closed doors is of utmost importance to johnson, who has long been wanting to do more in the way of new media and sculpture.

“I feel called to just do more than just depict pictures on a canvas. That’s no knock against people that are going to do that and that’s going to be their life, but I want to do something that ultimately will be there for a longer period of time,” he explains.

His latest pursuit is a Environmental Architecture and Design at Clover Park Technical College. He hopes that architecture and environmental design will equip him with the tools to foundationally understand how things come together, and to create change on a more impactful scale. The fact that an “anything is anything” mentality has led johnson to architecture will be significant, moving forward; the field of study notably lacks representation from the Black community, despite the abundance of current conversations around equity and reparations through land use.

“I want to be able to build things… and I can look at places that are around my community or establishments that are affecting my community, and be able to go in there with, ‘Here’s a way to create change,’ instead of just, ‘Oh yeah, we should just… raise money to build something,'” says johnson. “That will ultimately be my biggest goal in life: to be able to fabricate and design buildings.”

However, despite his ongoing work for and about Black people and what he knows to be clear intentions regarding his work, johnson still struggles with the same day-to-day conflict as any artist who is deeply interested and invested in societal change.

“Every opportunity I get has always been around us, [but] I’m always wondering if I’m doing enough for us, because there are people that are marching right now, and I’m at home creating art,” reflects johnson. “But it’s always been about trying to make sure that I’m just giving back in every way possible that I can, and making sure that I’m constantly shining a light on what’s happening.”

barryjohnson.co

Ω