It’s 9:00am on the dot when I pick up my phone to dial a New York number.

It rings once.

“Vivian!” the voice on the other line exclaims. Yes — not states; not says — but exclaims! As though we had known one another for years, and he had long been expecting my call.

Because it’s rare for any musician to respond to a minor indie journalist in this way, I’m caught off-guard and bumble through a number of clumsy mumbles before I apologize for my incoherency. The voice on the other line consoles me; the bumbling is “charming,” it says, which henceforth lifts the spell. I start speaking with some semblance of normalcy.

You see, I wouldn’t usually approach an elder in such an unprofessional manner — but today, I am speaking to the multi-instrumentalist and modern New Age music legend, Laraaji — and he feels so approachable that I’ve unwittingly spouted out a firehose of verbal flubber. He, on the other hand, remains perfectly composed, despite the fact that he has already done an exhaustive series of interviews similar to the one we are about to embark on. I am grateful.

Sun Piano, his summer 2020 release on the British label, All Saints Records, marks Laraaji’s light-hearted, glowing return to piano after decades of focusing more on other instruments. The first of a three-album series recorded in Brooklyn Unitarian Church and lovingly sequenced by ongoing collaborator and Warp Records producer Matthew Jones, Sun Piano will be followed in the fall by the more somber Moon Piano, and finally, by Through Luminous Eyes, a hybrid of piano and zither, which references the idea of “seeing in a new age… at the frequency of light [and] the light body.”

Sun Piano, his summer 2020 release on the British label, All Saints Records, marks Laraaji’s light-hearted, glowing return to piano after decades of focusing more on other instruments. The first of a three-album series recorded in Brooklyn Unitarian Church and lovingly sequenced by ongoing collaborator and Warp Records producer Matthew Jones, Sun Piano will be followed in the fall by the more somber Moon Piano, and finally, by Through Luminous Eyes, a hybrid of piano and zither, which references the idea of “seeing in a new age… at the frequency of light [and] the light body.”

At the time of this interview, the United States remains in quarantine due to COVID-19, and Black Lives Matter protests are in full swing. Hence, as I launch into our conversation, I am eager to satisfy my curiosity about Laraaji’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s. In the early ’60s, he had been attending Howard University, a historically black college located in Washington, D.C., so a large part of me hypothesized that an artist who makes healing music would undoubtedly have been an outspoken civil rights advocate as well.

But that assumption, I soon realize, is unjust; it places limitations on the multiplicity of human experience and severely limits the multi-dimensional nature of spiritual beings. While Laraaji touches briefly on being involved with NAACP prior to college, it is merely a touchpoint — and it takes me some time to figure out why I don’t find his lack of political engagement disappointing.

“From ’66 to ’72, I moved away from Washington, D.C. to New York to pursue comedy and acting and filmed television commercials,” Laraaji recalls. “That probably led me to investigate spirituality and meditation and altered states and different kinds of mind-consciousness practices, in order to feel more secure about being in the mass media.”

His investigations into consciousness have since unfolded in fascinating ways — including a number of wondrously creative “life is stranger than fiction” moments that have subsequently redirected the course of his life. As someone who experiences similar things, I want to dig into the roots of this universal magic… but I’m nervous about tackling such a daunting topic.

Hence, I slowly and awkwardly venture, “This is a very pointed question, and a very large question… but how would you summarize your spiritual beliefs, in general?”

I then hold my breath, fully expecting some sort of long diatribe; some kinda unwieldy verbal tome or epic oration which will stir my senses and move my spirit —

Instead, Laraaji pauses for a second to smack his lips, then simply replies:

“This moment.”

…

A brief pause.

Laraaji’s spiritual beliefs are “this moment”?

We both burst wildly into laughter.

It feels too abstract to make sense. But when one understands how Laraaji embraces “this moment” as a way of being, one uncovers the many profound and life-changing “this moment”s that have illuminated his path towards becoming an artist and healer. This interview investigates a number of them.

“This Moment” of Discovery

When it comes to Laraaji’s music career, nearly everyone has a million questions about how he got started. For most journalists, the line of questioning always ends up focusing on Brian Eno, who helped produce Laraaji’s first international album, Ambient 3: Day of Radiance, in 1980. It’s a fascinating connection — but I tend to find Laraaji’s colorful “this moment” lead-up to be much more fascinating.

“I was at a pawn shop one day in Queens, and a strong guidance — an internal guidance — pointed me to swapping my guitar for the autoharp in the window…” recalls Laraaji. “[The voice] was very clear. Very warm, super-humanistic. It felt like it was a great, great, cosmic grandparent with all the tenderness, goodwill, and gentlest compassion of a teacher who can only make a suggestion, which is up to the student to follow.”

And follow it, Laraaji did. That moment happened around 1974, and guided by the desire to hold onto the feeling, Laraaji spent years developing his sonic vocabulary for the instrument.

“It was apparent to me that this guidance was taking me in a direction that I didn’t know was available to me: New Age music,” Laraaji explains. “It was deeply confirmative — in that there was some intelligence that was accompanying me on my journey in life… and it gave me a sense of security and trust about my life, which took away any anxieties I had about survival or my own existence in this Earth plane.”

“It also showed me just how groovy and funky the spirit can be,” he adds quickly, “that the spirit could actually monitor me in a pawn shop, and make a suggestion like, ‘Take that autoharp,’ and I thought, ‘How rubish!'”

In the years to follow, Laraaji earned his living busking in places like Lower Manhattan’s Washington Square Park. It was in the late 1970s that Brian Eno chanced upon him one night and left an invitation for him to join an ambient recording project. Their collaboration, Ambient 3: Day of Radiance, opened doors for Laraaji to share his celestial music at consciousness expos and conferences around the country for decades to come.

With such incidents charting the course of Laraaji’s musical career, I wonder aloud if anything ever surprises him anymore. He doesn’t hesitate when he mentions he’d been caught off guard just a week prior, when a camera crew from Nike had been in his home, shooting an abbreviated version of his laughter workshop. Known around the world, Laraaji’s whole-body laughter workshops are downright yogic; they provide interactive, “therapeutically silly” opportunities for adults to release tensions and anxieties through the physical practice of play, and hence be elevated to a place of receptivity or relaxivity within a group setting.

“Laughter work is a total workout, and it takes advantage of the health benefits of laughter,” says Laraaji. “During that entire workshop, people are just really distracted from outside world concerns and heaviness, and they come into a lightness, a playfulness, a joy, and also, natural spontaneous stillness, bordering on real meditation.”

During this particular home recording session, Laraaji explains, “The audio person had never heard my music before. And so, I went into about five minutes of this celestial zither music — like real trance — and he told me afterwards that he left his body. He had gone into an expansive sense of space and time.”

Such incidents are not unheard of for Laraaji, whose numerous public performances through the years have led him to an important realization: being a musician that plays spiritual music comes with its inherent power and responsibilities.

“After a concert at the college auditorium, [someone] had gone so deep out of their bodies that a hypnotist in the room had to go over and talk this person back into their body…” Laraaji says, detailing a conference during the early ’80s. “It was the moment that inspired me to be mindful of bringing people back into the body after a concert or a workshop.”

Laraaji now closes his workshops with a song called “Happy Feet Song,” “to help people ground in the body after going out into unfamiliar abstract space and time.”

“This Moment” with The Sun & The Moon

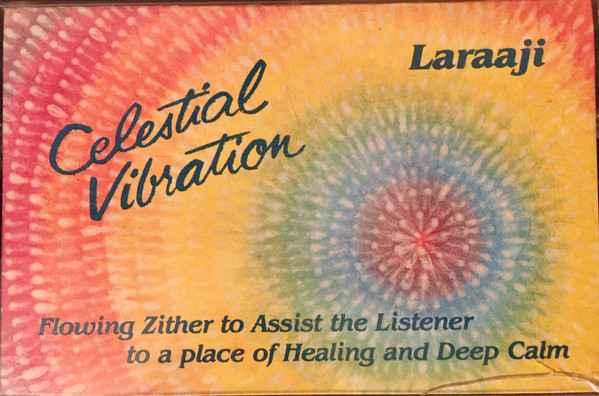

Laraaji’s extensive discography contains well over fifty album releases, dating all the way back to Celestial Vibration, Laraaji’s debut LP, which was released in 1978. Of these, this year’s Sun Piano is the fifth album, at minimum, which features the word “sun” in its title. Others include 1984’s Sun Zither, 1987’s Sol, and 2017’s two paired releases, Sun Gong and Bring on the Sun.

Something leads me to believe that Laraaji’s fixation on the sun — that mythological symbol for power, influence, strength, and masculine yang energy — goes far deeper than this article can even begin to elaborate on. It all began at Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza in the mid-1970s, during one of young Laraaji’s days of temporary homelessness.

Something leads me to believe that Laraaji’s fixation on the sun — that mythological symbol for power, influence, strength, and masculine yang energy — goes far deeper than this article can even begin to elaborate on. It all began at Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza in the mid-1970s, during one of young Laraaji’s days of temporary homelessness.

“I felt isolated from the rest of the world, because the rest of the world was busy with its 9-to-5 life and all that, so I was sitting on a park bench from noontime, gazing up into the sky, and there was the sun, just beaming down [with] radiant, compassionate, soothing energies,” Laraaji remembers. “I felt I was having this one-on-one special time with the sun and realizing how dear a beautiful being it is, up in the sky, radiating its warmth interpersonally for all. That impressed me, deeply.”

What, then, of the moon? I ask.

To this, Laraaji seems relatively at a loss, for the first and only time during our conversation — and it is to be similarly noted that unlike his deep relationship with the sun, he has yet to have any albums with “moon” in its title.

“People talk about the moon affecting the tides, and I still haven’t understood why it would be so…” Laraaji responds. “But it’s interesting, that question, because as I travel around the world, or within the United States, I can find myself in the room where I’m staying, or in the lounge where I’m getting a cup of tea, and I’ll look out of the window, and there’s the moon! And I’m wondering, ‘Is it just automatic that the moon’s gonna be visible to me every time I look outside of the window?'”

If one were to ascribe significance to such happenings, one might suppose that within the subtle, coy manner in which the moon has emerged to Laraaji, lies an informative allegory. The moon has long been seen as a subtle, reflective, intuitive celestial body, which symbolizes feminine yin energy; which holds power in more covert ways than the sun.

Together, the 2020 releases Sun Piano and Moon Piano form a pair of celestial sonic bodies, in meaningful conversation with one another.

“This Moment” with Mr. Love and Mr. Peace

In a recent COVID-era livestream performance for Boiler Room, an orange-clad Laraaji sits before a zither and clashes stylishly with Mr. Love, a giant, floppy green frog puppet with a helluva lot to say. Speaking as he does in throaty gibberish, Mr. Love is wholly unintelligible, so it’s a good thing Laraaji is present to play the role of ventriloquist translator. The resulting set is a fascinating hybrid of sweet, sweet zither and head-scratching comedic relief, by way of Mr. Love’s scat-sung spiritual lessons.

What’s the deal with that frog puppet, I basically ask — and the last thing I would have expected is for Laraaji to laugh and tell me, “Well, there’s a mystical story to that,” then launch into yet another “this moment” encounter. It was the mid-’80s, and he was in West Palm Beach, Florida for a conference, staying at the home of the event’s secretary.

“One day, she came home from her job, and says, ‘You’ve been cooped up in this house; why don’t you come to the mall with me?’ and I just said yes, as though that were what I was supposed to do at that time of day,” Laraaji recalls. “I went with her, and she parked her car and said, ‘I’ve got to do some things in the mall; you can meet me back here in half an hour, at the car,’ and without even thinking, I walked across the parking lot to this toy store, walk in through the door, walk down through an aisle or two, turn to my left, turn left again, look down and then, there were these two furry frog hand puppets. I just picked them up, walked to the cash register, paid for them,went home, and just started informally hanging out with these friends.”

Only in Laraaji’s world would “these friends” become Mr. Love and Mr. Peace, two living symbols of the musician’s powerful and meandering intuition, manifest in physical form. Embedded with quirky personas, the two friends have shown up at Laraaji’s meditation and consciousness conference performances over the past forty years.

“They’ve been a very wonderful instrument for me to bring up subjects that if I brought up by myself, I’d be boring or not interesting,” explains Laraaji.

Dr. Love and Dr. Peace are, in fact, anything but boring or not interesting. Though they have their given names, they can also morph into other characters, depending on need, and are animated by the kind of improvisational wit that reminds viewers of Laraaji’s early pursuits as a comedian and actor.

Twenty minutes into the Boiler Room stream — which also happens to be a benefit for the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund — Mr. Love suddenly begins speaking in a cadence and tone so hilariously jarring that I feel fixated and cartoonish myself; with eyes bulging out of my head and jaw dropping to the floor, I am positively buzzing and unable to look away.

“When we live in a world of duality and otherness, eventually, we run out of space and we start getting grumpy. It’s called the 3-dimensional grumps. We get grumpy, we complain, we’re unhappy, we’re unsettled; we want something more,” Laraaji starts translating, thus setting the foundation for an investigation into the concept of “AS-ness” — of being one with the present moment.

“As light. As light. Go as. Everywhere you go, be sure your AS is with you,” he starts, led by Mr. Love’s blathering guidance. “When you are in the shopping place, you are as light. You take things lightly, you see things lightly, you respond lighty. You move as light. Do not get your AS bent out of shape. Hold on to your AS. Hold on tightly to your AS. In your morning, when you wake up, wake up full of AS. Confirm your AS-ness. I am AS: oneness. I am AS light. I am AS great. I am AS grace. I am AS attitude of gratitude. Be AS. Everywhere I go, I am as AS.”

“This Moment” in Elaborate “As-Ness”

Ah, “AS-ness.” By the end of our conversation, which ends at exactly the one-hour mark, I guess I’d become comfortable enough with Laraaji that it’s time to get to the next level of inquiry.

“Embracing AS-ness can be difficult for people,” I ask, “and I was wondering… what would you say as advice or a way for people to engage in that?”

Laraaji’s response felt so channeled — so essay-like and so complete, despite being inserted between what had otherwise been our relatively casual and playful conversation — that I received the insight into his spiritual beliefs which I had initial hoped for.

Thus, I will transcribe here, Laraaji’s word-for-word advice on how we can each embrace our AS-ness:

Practice — and the practice would be finding a breath practice; finding a yoga practice; finding a hobby or an artform that allows you to dwell in extended present time. The idea is to get to a place where you drop your title, your names, and you’re just being present. You can do it by just sitting in an easy chair for fifteen minutes. Just strip away every title that has ever been used to refer to you, one by one by one — all the good titles, all the proud titles, all the ugly titles. Be where it’s just the “I AM” that has no title. The I AM is a weightless, transparent place of present time. The I AM is continuous present time. And in the I AM-ness, if you’ve taken off all the titles, one realization you might come to is, “Wow, worry, anxiety, and heaviness does not belong to me; it belongs to the titles.”

The practice of getting away from the titles for 20 minutes, a day, or a half an hour — or make it your own ritual — is a way of breathing the continuous present moment. There, I find I really learn the non-relative presence. The self that is not in relationship; the self that isn’t coming from a birth; the self that isn’t going towards a death. A place that is just present as… the eternal now. The AS-ness.

That teaching is about my observations of religious teachings, which are to keep listeners in the thought that they’re moving toward a perfect world, or they’re moving toward heaven, or they are trying to find God or spirit… and in deep states of realization, my realization is that we don’t find that place until we go as that place. That we don’t find heaven until we walk as heaven. We don’t find peace until we move as peace.

The big trick is: how do you switch from going toward a vision to being as the vision? It’s a challenge for the intuitive imagination, but if one hangs out with it for five days, 21 days, maybe a year… then a breakthrough comes, where one catches that AS-ness is where the party really is.

“This Moment” in Visualizations

Laraaji describes the experience of being immersed in AS-ness and playing music as “having my cake and eating it too.” In such states, he often uses visualizations to send conscious intentions out into the world — a practice which looks, sounds, and feels multi-dimensional, to say the least.

“If I feel that I’m in an audience and there is much anxiety, I will intentionally let the music reflect myself breathing a very yogic, relaxing breath so that the music will hold space for relaxed, unrushed breathing,” Laraaji explains. “Other times, I’ll hold an image of intuitive imagery of angels whose form is more on the level of an etheric, crystalline body form, that maybe just dips into this three dimension and back out, but their bodies will walk in through and out of this dimension while I play music — so music for angels dancing.”

Many other examples exist; Laraaji has a stream of go-to options for his visualization practice. He might imagine, for instance, that listeners in an audience are tapping their feet joyfully, and his intention would then be to play a type of music “that supports the visible behavior of a joyful body tapping their foot.”

“I’ll [also] use imagery of someone in deep centering and stillness, maybe six feet from me,” explains Laraaji, and then play music to “support their being in that place [while] being mindful to not distract or interrupt that place.”

As one ventures deep into the realm of AS-ness, and “this moment,” the abstractions lead to only more questions. One of these questions, for me, is how someone who is so invested in the present moment might envision his future as a musician presently in his late 70s.

“I’m letting it come moment by moment,” Laraaji responds, perhaps predictably, and perhaps not. “I’m peacefully impressed and surprised where it has taken me here.”

Yet, as we’re dreaming boldly in this new decade, if there were one fantasy Laraaji could have about his future, he says, it would be a new form of music-sharing on a global level: one which is more vertical, spontaneous and trance-inducing — and allows masses of people to immediately drop into a sense of celebration and unity.

“This music may not even be playable by a musical instrument; it may just be a group of artists, healers, or practitioners deciding at some particular time to be a united channel for transmitting a global sound healing experience,” he explains. “I think of my future as being quite a unique experimental realm, experimenting with tone, experimenting with color and light to bring about a new platform; a new understanding of what healing can be on the planet. Healing means people moving around with a greater sense of peaceful connectedness to everything.”

“This Moment” for Rest

Towards the end of our conversation, Laraaji surprises me by bringing us back to the topic of the current Black Lives Matter movement. What he says helps clarify his contributions to social justice and collective liberation, if one is open to seeing spiritual work in such a way.

“In the midst of what we call racial issues is the equilibrium of the eternal universe. Maybe we tap into it when we go to sleep, or we wake back up and we’re out protesting. But I support that this inner continuum is there and that it shouldn’t be ignored for the sake of outer protesting, but that there should be a balance,” Laraaji explains. “Musicians can help bring the awareness back to this place, however temporarily… people who are out there active in issues deserve a break. Whether it’s a Miller Time break or a come to be still and feel the underlying frame of reference break.”

“We forget that underneath [the protests] is a platform that will still be here,” he continues, “and that we can rest and be recharged from it.”

In the way that Laraaji has discovered giant frog puppets can be useful in presenting abstract spiritual lessons, so too is the importance of spiritual music for healing and transcendence. By creating meditative sonic tools for listeners to be lost in their own unique “this moment”s, Laraaji provides a backdrop for learning to embrace our individual relationship to AS-ness.

To put into simpler terms, Laraaji uses music to create access points for a society that is otherwise poorly equipped to fully embrace living in a state of higher vibration and consciousness.

It’s difficult-to-quantify work, but that doesn’t mean what Laraaji posits is impossible.

And I think we can certainly agree that it would be welcome.

In closing. Go with good vibes.

Ω