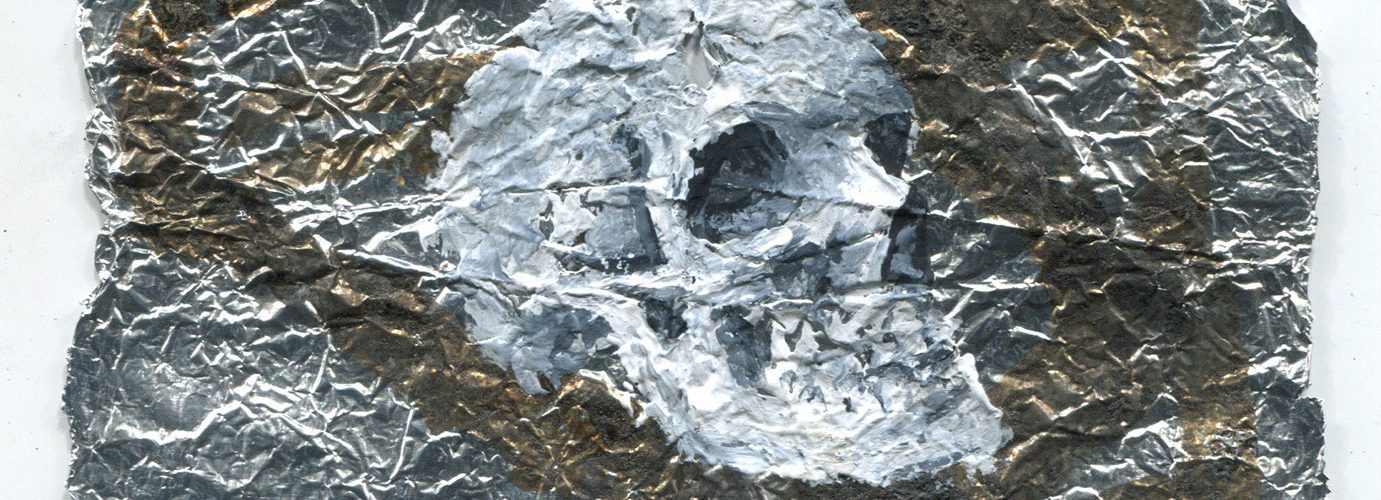

Gouache on fentanyl-stained foils.

Nature in the Pacific Northwest, Visualized

On a rainy Pacific Northwest day, I visit Baso – not his real name – at his home and art studio within the historic Bemis Building, which is a historic brick edifice in Pioneer Square. Today, because the building’s elevator is broken, Baso has transferred his living quarters and art studio to the ground floor. His artwork is everywhere within the cavernous space, ranging in size and style.

I’d first seen Baso’s work in the early 2000s, when he had developed an eye-catching painting style which involved regional animals, accented by colorful Impressionist brushstrokes. The aesthetic had a friendly, welcoming feel which paid homage to Baso’s childhood growing up near Tiger Mountain State Park – a lush area of forest connected to a network of mountain peaks, located in the suburbs outside of Seattle.

Rendered in this style, a number of Baso’s recent pieces tell the story of animals during the tragic 2018 Paradise Fires in California. The wildfires made international news after they burned 153,336 acres and more than 18,000 structures, decimating the area.

“I was thinking about the animal impact [during] the fires. That wasn’t really being talked about,” Baso explains, of a story that inspired one of his paintings, entitled Savior Fox.

“You hear a lot about: this many houses [and] this many people died… but I heard the story about this fox,” recalls Baso. “This guy saw everything burning around, and he saw this fox run down this little ravine, and he followed it. The fox went and found water… the guy went and got into the water. Everyone in his family died. Everything was burned, but he was saved by this fox.”

© Baso Fibonacci and Jean Nagai, Escaping a Burning Culture, 2017. SODO Track, Seattle. Photo by @wiseknave.

Roar, 2023.

Baso admits he used to have a habit of working in one visual style for years. But while he still uses this particular style of animal artworks for commissions, he has begun to move away from it for personal works. His intention is now to familiarize himself with a number of different artistic styles, so that he can shift accordingly with the needs of each painting.

“It got to a point where I could do it in my sleep. It still took time and still was challenging, but it’s gotten to a point where it’s really a formula, almost,” he shares. “I’m really enjoying painting from life and the depth that that gives you to be able to explore more dynamic work.”

Life on the Street, Visualized

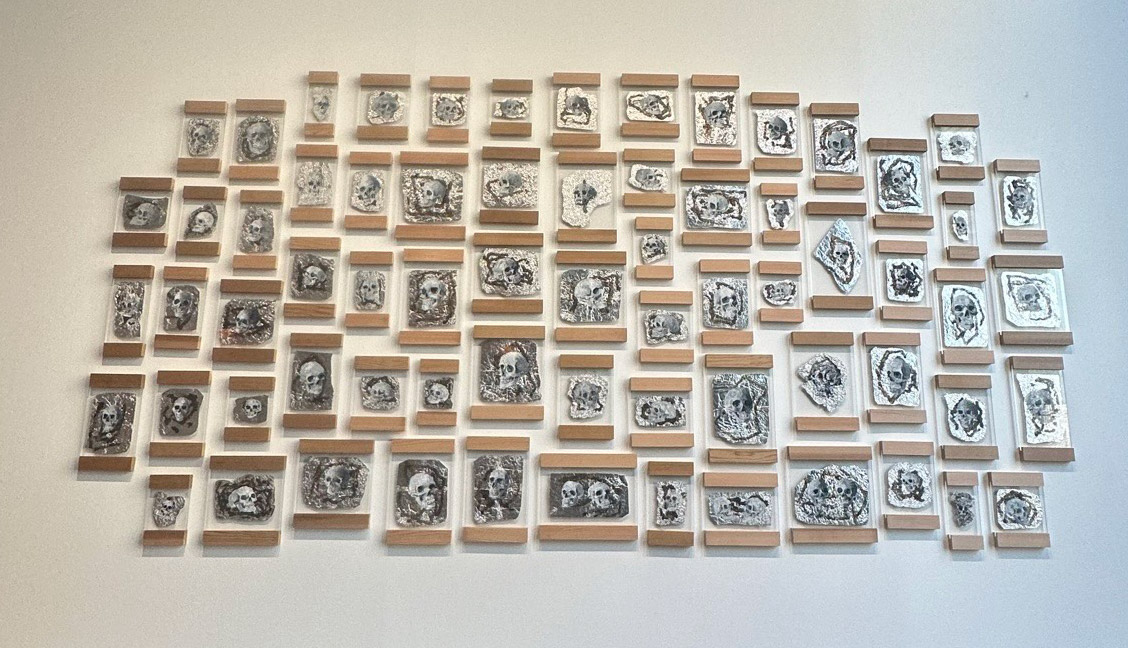

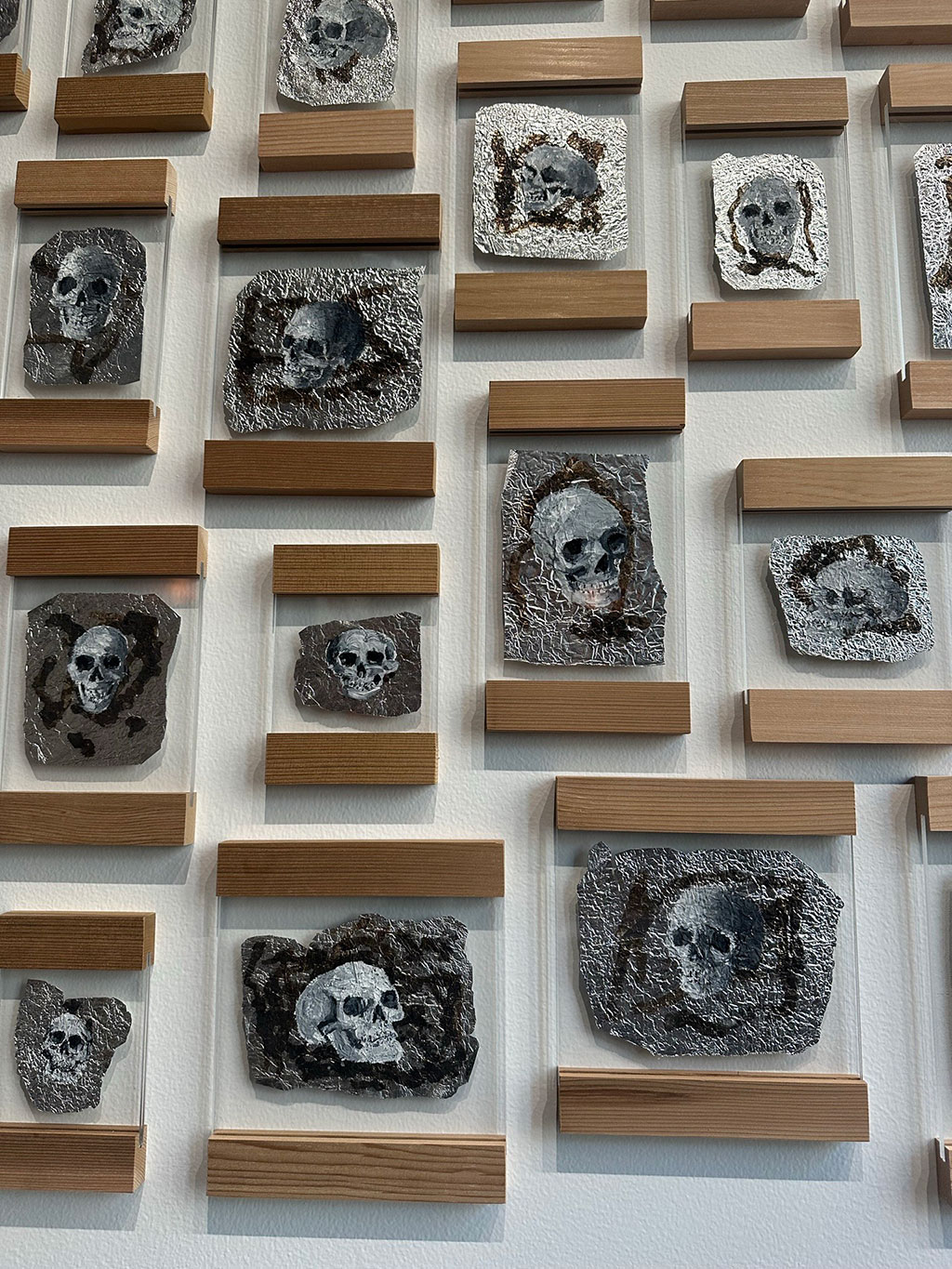

The idea of painting from real life brings me to Baso’s latest series, which is as of yet untitled. According to data provided by the local government, an estimated 200 people may die this year in downtown Seattle due to fentanyl use. To represent each death, Baso is painting a skull on a piece of foil which had been previously used for smoking fentanyl. All 200 will be displayed together, so that the enormity and totality of fentanyl deaths can be seen and felt by viewers.

While Baso tries his best to avoid direct statements about the fentanyl deaths and prefers for viewers to “read from it what they will,” his recent works do hit differently than his animal paintings. Perhaps it’s because fentanyl has become a public health crisis in many major cities and as such, holds a natural heaviness. Or perhaps it’s because Baso’s latest series gives voice to people who are often overlooked and counted only as dehumanized statistics.

“You read these figures about 200 people dying in downtown [every year]. It’s a figure; it’s a number…” he says. “But seeing something quantified… brings awareness of how many people are actually dying in a way that numbers and figures don’t.”

Gouache on fentanyl-stained foils.

Though Baso does not use fentanyl himself, his work comes from an authentic place. He knows active fentanyl users – including a friend who contributes foils to his artistic practice – and speaks to them often about their ongoing struggles.

“I’m around downtown all the time. I like to talk… [and] a lot of people are smoking fentanyl,” he explains. “Fentanyl is an opiate. Opiates relieve pain and it’s not just physical pain. It’s emotional pain… a lot of people are just trying to escape from whatever’s happened to them all the faster.”

Yet some audience reactions have been rather surprising for Baso. One person, for instance, suggested that he include a content warning with his work, so that viewers knew what to expect before entering the gallery space. Some others have misunderstood the context of the work due to their lack of connection to the fentanyl crisis.

“[Some people] are not educated about what is going on, basically,” Baso comments. “They take some while to understand that those are actual fentanyl foils that people have smoked off.”

Conversely, Baso has found that those with an understanding of fentanyl or know people who have passed from its use are frequently touched by his artworks.

“I had one woman start crying,” he says. “I think they just get it immediately, where I think some other people don’t really.”

Society’s rapid shift from heroin to fentanyl contributed to Baso’s impulsive decision to use foils as a canvas. He remembers a show he did around 2017, when he had painted on detritus he found around the Pioneer Square neighborhood. Nearly everything was on paper. One of the few exceptions was the skull he painted on a used piece of foil.

“That was before fentanyl was really around. I think it was heroin,” he explains. “[Closer to 2019 or 2020,] I started to notice that it went from having syringes on the ground all over to foils, almost like within a six-month period… in my memory, it seemed like it happened overnight.”

The Blade, acrylic, encaustic, enamel, spray paint and foil on canvas, 140″ x 76″. In Summer 2023, Baso showcased this large mixed media piece at a pop-up gallery event, XO Seattle. It featured a composite of various images from an area on 3rd Avenue nicknamed “The Blade,” which is an area that has roused police attention since the ’70s and ’80s. The street has long been associated with drug use and distribution.

Mikey, acrylic on canvas

Through Baso’s work, those familiar with fentanyl are reminded that it is significantly more fatal and addictive than heroin. Some batches are so strong, for instance, that they can cause withdrawals near instantly. Regardless, Baso is non-judgmental about the reasons people might use – and he recognizes the diversity within the individuals who have become users.

“I have a lot of friends that are addicts, and I think [fentanyl use has] kind of been looked at very black and white, [as if] all fentanyl users are just dirty and living on the streets…” Baso says, of a mentality that feels overly-simplistic of the reality on the ground. “I know people that have jobs and carry on pretty normal lives that use fentanyl.”

“It’s not just… monoculture… there’s different types of people [who] use it,” he continues. “It’s just part of our culture.”

Still, Baso is well-aware of the snowball effects that may come with using. One of those is limb loss. An epidemic that is often undiscussed, amputations can cause great distress for fentanyl users; it can land them in hospitals, where they are forced to face their addictions or be subject to external judgments.

“What I’d like to do is do a show with the fentanyl foils, portraits of people missing limbs from fentanyl use, and then have weekly talks from people that are affected by the crisis…” Baso explains. “I’d really like to have active addicts talk about what it’s like to be using fentanyl, to talk about withdrawals, talk about what it’s like living on the streets, talk about… how they’re treated. Maybe an ER nurse talking about what it’s like to see all these overdoses coming in… maybe parents of people that have passed away.”

Baso hopes to launch such events by mid-2024. In the meantime, he will continue to collect foils, be in community with his friends downtown, and keep tabs on the ever-growing number of fentanyl deaths.

Ω