Installation view, Songs for Ritual and Remembrance, Arthur Ross Gallery, University of Pennsylvania. (Credit: Emily Pothast)

Upon entering the Arthur Ross Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania, one encounters a recording of the hymn “Sit Down, Servant.” The people singing are relatives of the artist Adebunmi Gdabebo; the occasion is a funeral at the Old Jerusalem Church, located on what was once the True Blue plantation in Fort Motte, South Carolina. The building still exists but it is no longer used as a church. Only vestiges of its original purpose remain, like the cemetery across the street where many of Gdabebo’s ancestors are buried. Installed in the gallery are two wooden pews that once stood in the church, hand carved by members of Gdabebo’s family over a century ago. While they have held up beautifully to repeated use, there are worn spots in the finish that bear witness to all the bodies that have sat in them through the years. Paired with the music, they permeate the gallery with physical traces of human presence.

A few weeks after I viewed this exhibition in person, I spoke over Zoom with my friend Emily Zimmerman, who curated it. She tells me that the Old Jerusalem Church is significant because it was the first institution that Gdabebo’s formerly enslaved ancestors built after their emancipation. “It was the first thing they did with their free will,” she says.

Hanging on the wall near the pews is a companion piece titled “Remains, piece of Balcony Baluster” – a series of seven architectural elements salvaged from a home built by Gdabebo’s ancestors about a decade earlier, before they were free. Like the pews, these balusters are weathered from years of use.

Adebunmi Gdadebo, “Pews,” 1890. Original church pews. Courtesy of the artist and Claire Oliver Gallery, New York. (Credit: Emily Pothast)

Unearthing Histories

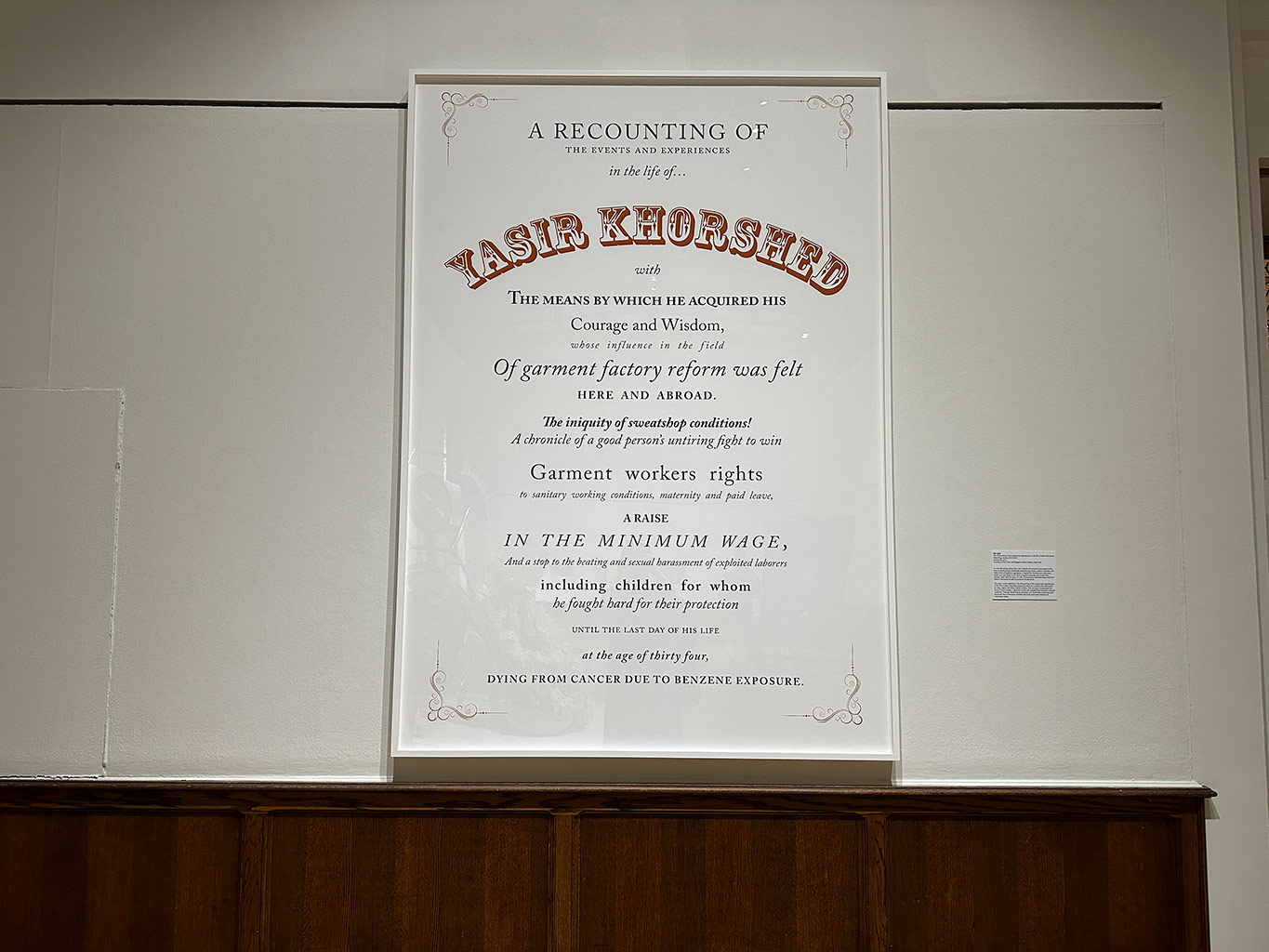

In the context of the exhibition, these found object installations are in dialogue with Gdabebo’s handmade works, which incorporate commodities like indigo dye, cotton, and rice, along with human hair and red clay soil dug from the plantation where these commodities were produced. They are also in dialogue with the work of three other artists: Ken Lum, whose monumental typographic piece commemorates both the accomplishments and the exploitation of garment workers; Mary Ann Peters, whose latest addition to her “impossible monument” series uses silk and glycerine to honor 19th century female silk workers on Mount Lebanon in Syria; and Guadalupe Maravilla, whose multimedia assemblages are healing rituals in sculptural form.

Each of the works in this exhibition embodies a material history that merits our attention, but is often actively marginalized by those in power: for instance, South Carolina is one of several U.S. states that has recently passed laws limiting how the legacy of the institution of slavery can be taught in schools. Together, they perform a kind of historiography that can only be achieved by arranging objects and sounds together in space. We can talk or write about these things, but the effect can never be the same as being in a room filled by them; of listening to singing voices while contemplating traces of blood, sweat, and toil.

“The concept of reparative history is really important,” says Zimmerman. “It’s an exhibition saying, ‘Here’s the gap in the power relations as they exist now, compared to what they should be.’ In many ways, it’s trying to model a corrective sense of historiography.”

Adebunmi Gdadebo, “Remains, piece of Balcony Baluster”, 1848. Original balcony baluster of the McCord House in Columbia, SC. Courtesy of the artist and Claire Oliver Gallery, New York. (Credit: Emily Pothast)

Expanding Contexts

Zimmerman’s approach has developed through many years of curatorial practice, which may be traced back to her time as a graduate student at the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, and through the previous positions she has held, including as Director and Curator of the Jacob Lawrence Gallery at the University of Washington in Seattle. The word “curate” is often overused to the point of absurdity, as when people talk of “curating” their friends or their Instagram feeds. But the curation of contemporary art is a field with its own theory, practice, history, and ethics — the intricacies of which Zimmerman is currently teaching in her course, “Curating Contemporary Art,” at Penn.

“We’re in a moment of transition of what the term ‘curation’ means. It still refers to a specific set of activities which, since the beginning of museums, have included activities that had a certain hierarchy built into them,” she says, pointing out how the International Council of Museums (ICOM) recently changed its definition of a museum in an attempt to chart a more progressive, community-oriented vision for the field.

“In the past, I think that museums reflected certain classes of individuals and served certain classes of individuals. They were born out of rich people’s collections, and only became public many years after the first museums were founded,” Zimmerman explains. “The profession of curating has similarly been dogged by some old vestigial organs of aristocracy. The field has not caught up to an equitable distribution of funds where, for instance, someone can curate who does not come from a wealthy background.”

“All of this is in the background and informs a hierarchical approach to programming that is author-led,” she continues. “In the past model, there was the genius author curator who put together their show and said, ‘Here, the public, this is what you need to be looking at, contending with, thinking about.’ And the shift that’s taking place [now] is: rather than that author-led model, more of an audience-led model of asking, ‘What are the needs of the community? How can we serve those needs? What are the conversations that the people who trust us need us to be having right now in order to come to terms with our world?'”

Ken Lum, “The Recounting of the events and experiences in the life of Yashir Khorshed,” 2017/2021. Letterpress print, courtesy of the artist and Magenta Plains Gallery, New York. (Credit: Emily Pothast)

Over the past several years, Zimmerman has developed a practice of working within institutional parameters to make the boundaries between those institutions and the communities they serve feel more porous. As Associate Curator of Programs at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, she programmed a series of outdoor public performances called The Untuning of the Sky, which brought music, poetry, and film screenings to venues across the city. It was through this series that I first got to know Zimmerman from an artist’s perspective, when she invited my band Hair and Space Museum to perform on the Seattle waterfront.

She describes this series as an “aha moment,” when it occurred to her that she did not need to confine herself to art that fits inside a museum. “I realized, I can go elsewhere, and that I might serve community better if I thought more expansively about context.”

This expansion of context would define her tenure as Director and Curator of the Jacob Lawrence Gallery, the gallery inside the University of Washington’s School of Art + Art History + Design. Among the many projects she spearheaded here was the launch of an art journal called Monday, which published critical writing on the interface between art and the social worlds in which it is embedded.

When Zimmerman returned to her hometown of Philadelphia in early 2023, she set out to discover what kinds of public interventions would make sense in her new/old context. “Songs for Ritual and Remembrance grew out of a process of checking in with community stakeholders and saying, ‘What’s going well? What’s not going well? What do you see the students needing?,'” she recalls. “Because the students are always kind of our frontline audience – our first constituency. It’s where we can make a case for art and model productive relationships with artgoing to the students.”

She identified two key points as emerging from those conversations. “First, the students did not have the tools that they needed to deal with the aftermath of the pandemic, so they needed stronger toolkits to contend with the kind of emotional, physical, economic realities that they were encountering,” she explains. “The second thing was contending with the need to start a conversation with the community. Recognizing that this is a beginning of a many years-long process, one needs to begin somewhere, and there are ways that this show could kind of jumpstart that.”

Zimmerman mentions a handful of other recent Philly-based curatorial projects that have engaged with their broader community in ways she has found inspiring. These include Rosine 2.0, an interdisciplinary project using art as a collective method of harm reduction and healing, and Isaac Julien‘s immersive installation Once Again … (Statues Never Die) at the Barnes Foundation, which pointedly interrogates the role of museums in creating and perpetuating racialized hierarchies through a colonial practice of stealing and hoarding objects.

“It’s one of the best pieces of expanded cinema I’ve ever seen in my life,” she says of Julien’s installation. “It became something that haunted my brain as I was thinking about this show and thinking about: what are the other ways that community holds memory? And how, in an institutional context, can you uplift those moments while also putting together an exhibition that will be made up of objects? Guadelupe Maravilla was an artist that offered an answer to that question pretty early on because he creates objects that reference a history while also creating space for ritual.”

Over the course of the exhibition, this space has been activated by musical rituals – most recently a sound bath performed by tone scientist and healer Michael Jay. Maravilla was introduced to sound therapy while undergoing treatment for cancer; including a sound bath in the exhibition allows the gallery to become a space of collective healing.

Guadelupe Maravilla, “Disease Thrower #16,” 2021. Gong, steel, wood, cotton, glue mixture, plastic, loofah, and objects collected from a ritual of retracing the artist’s original migration route. Courtesy of the artist and P·P·O·W Gallery, New York. (Credit: Emily Pothast)

Mary Ann Peters, “impossible monument (the threads that bind),” 2023. Courtesy of the artist and James Harris Gallery, Dallas. (Credit: Emily Pothast)

The Politics of Aesthetics

One of the ways that museums have historically perpetuated hierarchical violence is through the aesthetics of the white cube.

“It erases its history,” says Zimmerman. “It hides behind the white walls and tries to say nothing, [as if] we are in an eternal present and nothing else has ever happened in this space. But you see it on the opposite side of the wall. You go beyond the white wall and you see all of the hole marks and the putty and the funny shelves that were installed for a particular time, because there’s no effort to scour away that palimpsest.”

The Arthur Ross Gallery is not a white cube. Its architecture is highly idiosyncratic, with oddly shaped window frames and waist-high wood paneling, making it a fitting environment for an exhibition about the ways that spaces and objects can embody histories.

“One of the things I enjoy about the Arthur Ross Gallery is that it says very loudly when you walk in, ‘I was once a Shakespeare library!'” Zimmerman laughs. “‘And also: ‘I’m built in a totally different architectural style than the building that I’m attached to (the Furness Building), and that difference has to do with the politics of aesthetics.'”

I ask her what curators can do to push back against the aestheticized politics embedded in the colonial history of museums, and she replies, “I think changing the methods and processes by which our work happens is the hardest and the most important thing – those quiet rhythms that determine when you do things. And also, changing the politics of hierarchy within the institution; letting go of some of that need for power or authorship, while also putting at the service of community all of the skills that a curator will have.”

“In some ways, I’ve been learning tools to think of myself as a facilitator rather than an author,” Zimmerman concludes. “In this specific case, I undertook some learning about somatic healing because I think exhibitions speak in a language of embodied space, so they’re well-suited to broach that subject.”

Mary Ann Peters, Emily Zimmerman, Adebunmi Gbadebo, and Claire Oliver. (Image courtesy of Emily Zimmerman)

Installation view, Songs for Ritual and Remembrance, Arthur Ross Gallery, University of Pennsylvania. (Credit: Emily Pothast)