A question posed to the viewer when they enter Jacob Lawrence Gallery is: “who gets to be surreal?” The show’s five curators — Brittney Frantece, Chari Glogovac-Smith, Fal Efrem Iyoab, Cassie Mira, and Eric Villiers — carefully selected Black artists in their attempt to answer that question.

“Some of them maybe were surprised; maybe they didn’t think that they would call their work Black Surrealist work,” says Glogovac-Smith. “But it just goes to show that surrealism is this really expansive sort of idea, generating many different ways that one can approach and view the world and also, view art. What might read as Surrealist to one person might not read as Surrealist to another.”

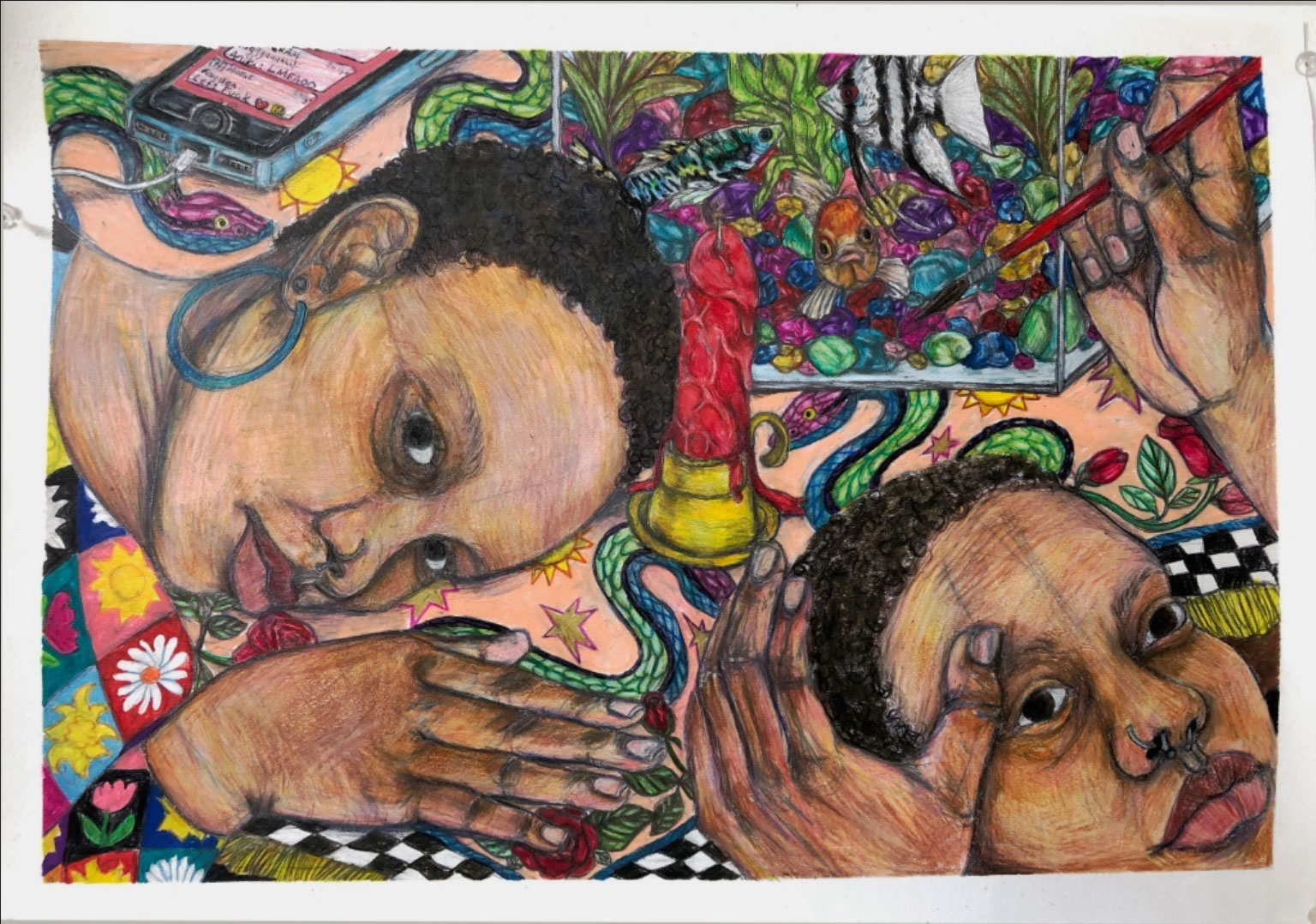

LaNia Sproles – Can a negress in distress do this?!, 2021, 10″ x 14″, colored pencil on BFK, pencil, marker

The Collaborative Curatorial Process

Using class conversations and research around the themes of the show, each curator invited two artists to comprise the final group of ten artists: Ariana Benson, Bereket Adamu, Brea Wilson, CHARI, Darryl DeAngelo Terrell, LaNia Sproles, Le’Ecia Farmer, Nahom Ghirmay, Ronald Hall, and SAMAR. No two pieces were the same. The artists used painting, collage, scent, sculpture, video, sound, and other forms of making to explore the ways in which Black dreams know no bounds.

Glogovac-Smith offers the reminder that both the artist and curators had “varying perspectives about what Black Surrealism might mean, could mean, and that’s sort of embedded in… the idea of Surrealism in general. It’s expansive and inclusive of many different ways of being.”

“For me, Surrealism is about engaging all the senses to access alternative, non-normative, and elusive ways of knowing and being,” says curator Brittney Frantece.

The five curators met individually with each of the two artists they selected “to have conversations about their works and their relationship to Surrealism,” according to Frantece. Later in the process, the curators were able to “discuss the artists’ works and practices” and how the curators could “respectfully display their work as a group.

While the topic of Black Surrealism and speculation seems to be especially culturally relevant today, it is not new. Artists from writer Amiri Baraka to visual artist Wangechi Mutu have been using imaginative art as a tool for Black liberation for decades. This information was imperative to the research the curators brought back to the group.

“We had conversations about the types of artists that we read to be associated with black Surrealism as individual curators,” recalls Glogovac-Smith. “From that sort of practice of going away, researching, coming back together, and having conversations, we were able to create this sort of collaborative, giant canvas that is a gallery space right and put together the show.”

Gallery installation photo featuring Nahom Ghirmay’s The Child Within (left); Brea Wilson’s Reflective Wholeness: Black Queer Identity in Multidimensionality, 2023 (back), LaNia Sproles’ Superstar, 2020 (right) SAMAR’s The Scentuary(center. (Credit: Brittney Frantece)

An Explorative Space

we sense, we remember we rest, we dream: We Black, We Surreal is broken up into three rooms. The first is a bright room that, at first glance, is set up in a traditional gallery structure. Yet it quickly becomes clear that it also challenges notions of what a traditional gallery holds.

Scents crafted by SAMAR can be rolled onto paper and carried throughout the exhibition and out of it. A waft of their comforting scent, “The Tea House,” allows one to imagine the subjects existing in the dreamscape environment found in LaNia Sproles’ portraits, which include the mixed media piece featured on the show’s flyer, entitled Can a negress in distress do this?!. A bench next to Ariana Benson’s poetry encourages stillness, reflection, and rest.

Frantece says that the placement of the art “allows for viewers to experience arts in conversation with each other.” Le’Ecia Farmer’s geometric bioplastic sculptures situated next to Wilson’s mirror lead viewers to think of what it means to define an ever-changing self in an ever-changing world.

Brea Wilson’s sculpture, a mirror titled Reflective Wholeness: Black Queer Identity in Multidimensionality not only encourages visitors to contemplate the multiple perspectives Black Queers hold, but also asks Black Queers to see themselves as they witness art. Meanwhile, scents such as “Speakeasy” use nodes of leather and smoke to transport participants into the “vivacious” queer culture of 1920s Harlem — a time where Black Queers were dreaming up the many possibilities in which they could exist in reality — not too dissimilar from the ways Wilson’s mirror does so as well.

“We had conversations about where the right scents needed to be and in what space to sort of invoke this idea of passageways and portals between ideas but also as people transition into spaces,” says Glogovac-Smith. “The poetry was also serving that function.”

Benson’s poetry, placed around the entire gallery, is a reminder to viewers that they are not in a traditional gallery space, but one of invention and expansion.

The dimly-lit second room is filled with large video projections paired with headphones, creating a balance of intimacy and eye-catching display. CHARI’s work reminds viewers of how Black people constantly have to imagine what could have been, what the histories of places really are, and ways to not be erased. Their portrait series, titled “MITCHELLVILLE 1862,” uses speculative AI historical photographs to reassert the presence of formerly enslaved peoples in Mitchelville, South Carolina — a place where developers are currently pushing their descendants off the land.

CHARI’s video, “THE CIRCLE, UNBROKEN,” puts into perspective the contrast of how Hilton Head Island, located two hours south of Charleston, was historically used by Gullah peoples, but now by wealthy white vacationers. It asks viewers to dream of the Gulluh peoples’ rhythm and energy that can still be felt on the land, regardless of who is there now. The work highlights that the imagination which comes from Black Surrealism is not always rooted in pure joy, but is always necessary.

CHARI – MITCHELVILLE, 1862, PORTRAIT # 2

The last room completely breaks away from traditional gallery norms and is offered as a place of rest. It is small, and there is no “art” on the walls. Inside of the room, one is washed in sound and scent. Darryl DeAngelo Terrell created ~a resting place~ to ask “the listener to experience freedom through its sonic registers.” While sitting in the room, participants are washed in sounds such as Roy Ayers’ 1977 R&B track, “Searching,” coated in star sounds. Bodies can also dive deeper into rest through SAMAR’s scents, “Speakeasy” and “The Tea House.”

For a moment, Black visitors can dream what it feels like to live outside of the confines of society’s restrictions. However, through the words of Benson’s “Drapetomania or the Existential Threat of Black Dreaming.,” they are still reminded of the realities of Black life in the context of the modern world. The poem grounds viewers in the nightmarish response to Black Dreaming and the violence that it has historically incited.

As Frantece says, “The placement, I hope, encourages conversations on salient themes in Black thought.”

The write-up in the front of Jacob Lawrence Gallery says that a goal of the exhibit is to “providing a new lens to contemplate Black being, living, presence, and knowing.” Curating in this way does just that. It is radical to curate with such care. It is profound to strip the exhibit of individualism by having multiple curators and multiple artists.

Ω