Three Promises Documentary Film Trailer

When I spoke to Srouji and Three Promises‘ producer, Marielle Olentine, at True/False Festival in March, it was a surreal moment for the accidental filmmaker. When Three Promises had its World Premiere at Visions du Reel in Switzerland in April 2023, his entire family had been in attendance. But Srouji hadn’t been able to travel to another event since the U.S. Premiere at Camden International Film Festival in September 2023. True/False was the first time he had left his home in the West Bank since Israel’s War on Gaza began in October 2023. Fortunately, Srouji and his family were the recipients of the True Life Fund, a grant given by True/False to “raises money and awareness for the subjects of a new nonfiction film each year.” Srouji intends to use the money to build a Palestinian film archive.

An Accidental Film is Born

The origins of the sixty-one minute film trace back to the early 2000s, when Israel retaliated against the Second intifada — or uprising against occupation of Palestine’s West Bank. Three Promises opens with a boisterous Christmas gathering of extended family. It’s an intentional choice to break any preconceived notions Western viewers may carry about cultural differences.

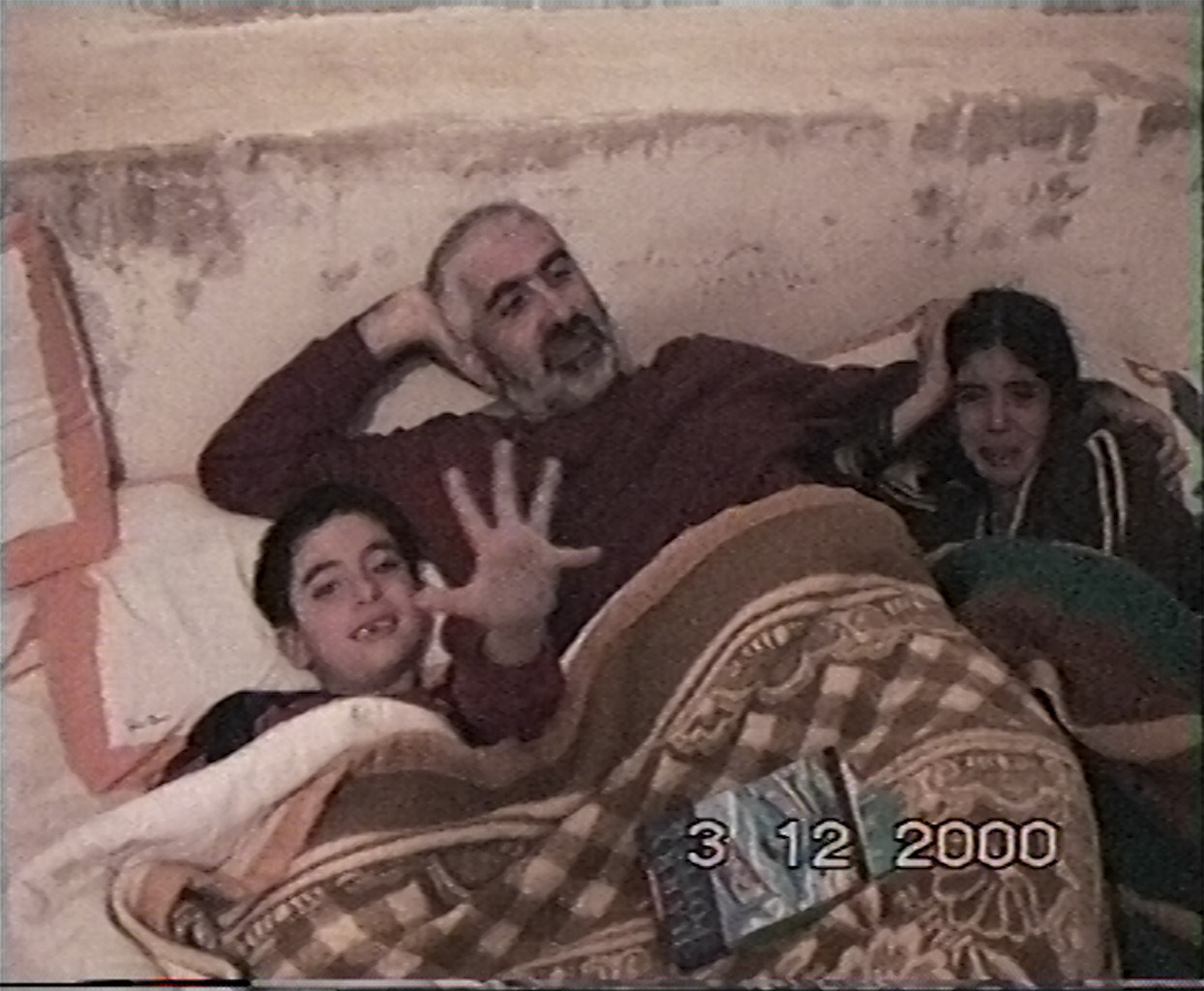

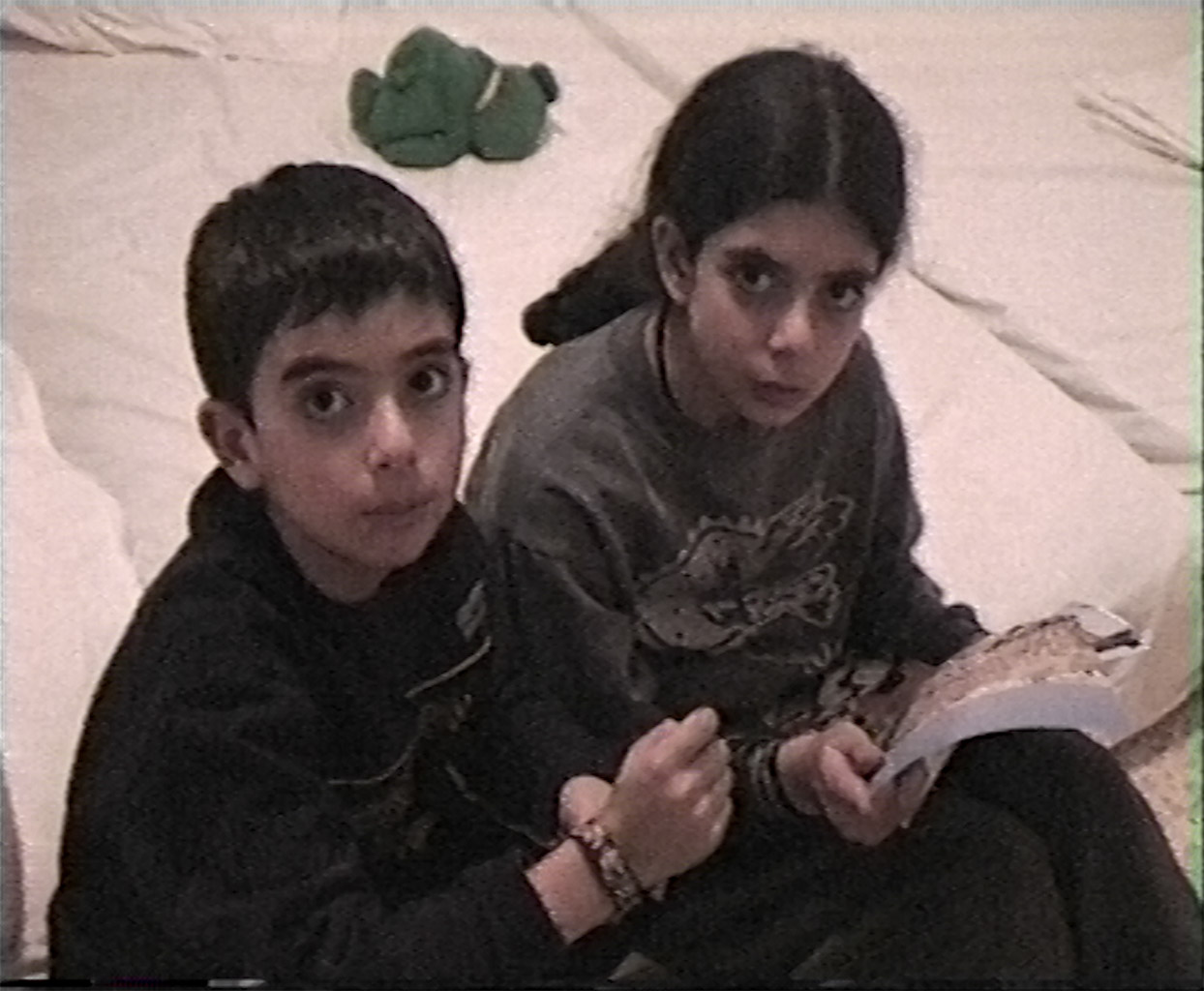

At the time, Srouji was a young kid living with his mother Suha, his father Ramzi, and his sister Dima in Beit Jala, a small town near Bethlehem. Suha, ever the avid home video cinematographer, captured typical family gatherings and everyday moments. She chose to keep the camera rolling even as her family’s daily life was interrupted by bombings that forced them to seek shelter under stairwells in the depths of their apartment building. In multiple heart-wrenching scenes, her family begs her to step away from the window where she films assaults on her city and shelter with them downstairs.

Fast forward to 2017, long after the family had fled their home in the West Bank and relocated to Qatar. Srouji re-discovered the home videos and realized that they told the story of one family’s struggle to survive not only the violent assaults against their city, but the traumatic psychological effects of war that threaten to tear them apart. In order to sculpt the home archive into a film, Srouji recorded multiple conversations with his mother about her memories from that time, weaving them into the film as voiceover to contextualize the inner emotional worlds and relationships among the family members.

The resulting film is striking in its stylistic simplicity and emotional resonance. The format of the home video offers an instantly familiar medium, capturing the idiosyncrasies of family life. Each person’s personality pops off the screen: the no-nonsense Dima, who is not easily comforted amidst the volleys of bombs and bullets flying through the night air; the calm and composed Ramdi, who is clearly a rock for the family; the “very organized” Yousef who attempts to distract himself and his family with fart jokes while they’re huddled in their grandparents’ basement; and Suha, a fiercely brave mother and relentless documentarian who holds the family together with love, wit, and vivacity.

Navigating the International Documentary Film Industry

After the True/False screening, I approached Srouji outside the theater, just as a march in solidarity with Palestine set off through downtown Columbia, Missouri. We walked together, and he remarked that it was his first protest. He planned to return home in two days.

“Yeah, it’s definitely been a lot to process,” he admitted. “I’m still processing the world premiere. That happened a year ago. So the process of what’s happening right now is even more difficult, but it’s been a beautiful journey.”

Originally, Srouji didn’t plan to submit to festivals and thought instead that he would just put the film on YouTube. That’s where Olentine stepped in and encouraged Srouji to pursue the larger international platform that the film deserved. Three Promises has now screened at many festivals across Europe, North America and the Middle East.

“It’s been overwhelming, getting random messages from people on Instagram, sending heartfelt messages after watching the film. That means the world to me,” he said. The ongoing genocide in Gaza heightens the stakes for Srouji, who still lives in Ramallah in the West Bank. “Today, it’s just that much more emotional with what’s happening in Gaza. I’m seeing the film in a different light. Certain things have become more of a trigger than they were before.”

At the same time, the film content feels less intense in the wake of the horrific atrocities committed against Palestinians since October 2023..

“I was particularly interested in hearing about what [Srouji’s] experience was like growing up in Palestine because I had met a lot of people in the diaspora,” said Olentine, who met him at University of California-Berkeley while the two were enrolled in the same graduate program in International Development and Sustainability. “My family had talked a lot about Palestinian history, but I had never actually met somebody who grew up there.”

When Srouji returned from winter break with his re-discovered family archive of home videos, they watched the footage together and Olentine affirmed his hunch that there was a film to be made. Like many independent documentary teams, they worked for years on Three Promises with no funding. Then, they were selected for the SFFILM Catapult Documentary Fellowship and then the Gotham Documentary Feature Lab.

The crucial resources helped the filmmakers build momentum around the project. They began winning more grants and meeting more mentors — but they were shocked when some respected film industry professionals started pointing them towards Israeli institutions for funding.

Srouji was incredulous. Describing his internal reaction, he said, “Like, are you serious? You’re joking, right?”

Srouji recalls declining funding from Israel and Saudi Arabia, then being put in the uncomfortable and unfair position of justifying his choices to industry players.

“We don’t fundamentally have an issue with Israeli funded projects or anything like that, but it’s the strings that come with that,” Srouji clarified. “I wanted the film to be raw and authentic, and I didn’t want anyone telling me what to do or what to take out. The industry was difficult at first, but we eventually found our allies, and they were super helpful.”

“But it was difficult navigating that, for me, at least personally,” he added.

“A beautiful thing that’s been happening too is that we’ve had filmmakers, both first time and more experienced, see this film as an invitation to make films about their own stories, using their own archives,” Olentine described. “I just think that that’s a beautiful thing that I would encourage people to do.”

After the difficult trip from the West Bank to Missouri, Srouji found the audience turnout, reception and the public demonstration of support for Palestine heartening.

“It’s super heartwarming being here… just seeing all the support. It’s so beautiful in Missouri; who the hell knew?,” he said. Nonetheless, he admitted, “A part of it feels slightly meaningless, because we’re just a drop in the ocean.”

Today, Srouji’s parents are in Cairo, Egypt. His sister, Dima, recently left Ramallah, where the two siblings had been living together for a few years. She relocated to London. As for Srouji? He couldn’t wait to get back home.

Ω