Le’ecia Farmer at ARTS at King Street Station, standing in front of Self-Portrait Tapestry, 2023, fabric, bioplastic, acrylic, raffia, cotton batting. (Photo credit: Chloe Collyer)

Carrying Their Stories

Some of the materials used in Space Cowrie, such as indigo and cotton, have a charged history for Black people of the African Diaspora. By crafting an experience which allows viewers to “have the space and the vastness to experience what’s coming up for them,” Farmer acknowledges the complex feelings which might be evoked. Without placing specific commentaries on each piece, the work is allowed to speak for itself.

Historically, many natural materials have non-consensually been under the control of human beings and subject to the destruction of the environment. Those same materials have also been in symbiotic, sustainable, and nourishing relationships with global communities. Working with natural materials is to work with living organisms that have their own histories; Farmer understands that when using them, the materials are “exchanging histories with us.” We carry their stories and they carry ours,” she says.

Laid out near the entrance of the gallery is a table of handmade bioplastics, which are proof of experimentation and play within Farmer’s craft. As she explains, “It’s too exhausting to be in an intense space all the time.”

A combination of gelatin, agar agar, food waste, and natural dyes are used to make each plastic. While the bioplastics pieces don’t have a specific use, they are a nod to sustainable practices used by Black folk both historically and currently. Sustainability, for Farmer, is a part of their culture.

“It’s a part of our ancestral ideology,” she explains. “To me, ancestral identity doesn’t mean just the past. All of that shifts. It’s relative on any timeline. We respect things. We respect people in our environment.”

Le’Ecia Farmer – Bioplastic Samples Collection, 2023-2023, agar agar, gelatin, glycerin, natural dye, activated charcoal, food waste, twine (Photo credit: Akoiya Harris)

When Past Present and Future Collide

When creating, Farmer allows “all the sensitive emotions come to the front” and allows themselves to indulge in joy. Joy is a driving force in their work; it even helps them find what form to use to convey certain messages. While their work is not always explicitly about the African Diaspora, much of what they explore is an effect of it. Themes of grief, trauma and loss — as well as themes of queer desire and the heartbreak that is endured living as a dark skinned queer Black femme — all show up in their work. Their life experiences inevitably inform their art.

Creating, for Farmer, is a way to process while being in communication with their ancestors — “kind of like working out the kinks of your energy that live in your body and giving them grace, giving them honor, giving yourself grace.”

They know that the energies they are working through is not just theirs, but those passed on from their ancestors as well. As a result, they are not looking for resolve, but for deeper understanding — since resolve will take more than their lifetime to happen. And although working through ancestral knowledge can feel heavy, discovering the methods and mediums to convey certain messages is seen by Farmer as an act of play.

“All of it’s just whatever comes from my experience, and what is remembered in my body — from everything that makes up my DNA, [but] all my ancestors and future selves as well,” explains Farmer.

Call and response is a grounding element in Black cultures across the world. The act of witnessing each other and responding can be seen in music, poetry, dance, church service, or even just when passing each other on the street. Farmer recalls a time their daughter was dancing outside on Capitol Hill and because her joyful energy put out such a strong call, three Black strangers responded by hyping her up.

That practice translates into how Farmer creates. For them, artmaking is not a linear process. It can be a “call and response between this energy I’m constantly downloading and feeling from my ancestors and from this palpable history, which often also could be flipped,” she explains. “They could be calling me [or] I could be calling them with my artwork, and they could be responding with this information.”

Oftentimes, grief and frustration come up for Farmer when they remember how these cultural practices were violently stripped from their ancestors. Artmaking was a way to pass information, hold history, and keep identity, by reclaiming an ancestral way of feeling that “never was validated by Western society, was discredited, tried to be erased, wasn’t taken seriously and to be honest, [and] not even fully understood most of the time.”

Various works by Le’Ecia Farmer. Clockwise, from upper-left: Raffia Seam Pants, 2021, raffia, cotton; The Desquamation of Everything I Built Up for the World to See, 2022, undyed and indigo-dyed raffia; The Self in Mitosis, 2022, wax, raffia, wool, plant matter; Calendar of love and repair, 2023, wool and raffia (Photo credit: Akoiya Harris)

Le’Ecia Farmer – Ode to Fledgling Outfit, 2023, knit top, crocheted raffia overtop, bioplastic and fabric skirt. (Photo credit: Akoiya Harris)

Many of the practices Farmer uses, such as weaving and quilting, have been self-taught. Through the process, they have realized that sometimes the body and spirit remembers, regardless of what the mind knows. When separating and weaving raffia, for instance, memories arise for Farmer of being in their mom’s salon and witnessing her braid hair.

Rituals like these are fragmented parts of the African Diaspora that have never left. As Farmer describes, these ancestral practices aren’t “lost because I feel it, even though I can’t explain it all the time. I feel it and I know it. It feels like I keep unlocking things that are trying to find me.”

“I experiment in a way that I still want to honor and respect the ancestral techniques. I don’t like the idea of ‘advancing,'” Farmer continues. “It already feels like all of our techniques are advanced, all of our techniques are profound, [and] all of our techniques are beyond written English texts. So I’m just playing around with it and mixing up some of the vocabulary.”

Ω

Gallery installation view of works by Le’Ecia Farmer. (Photo credit: Akoiya Harris)

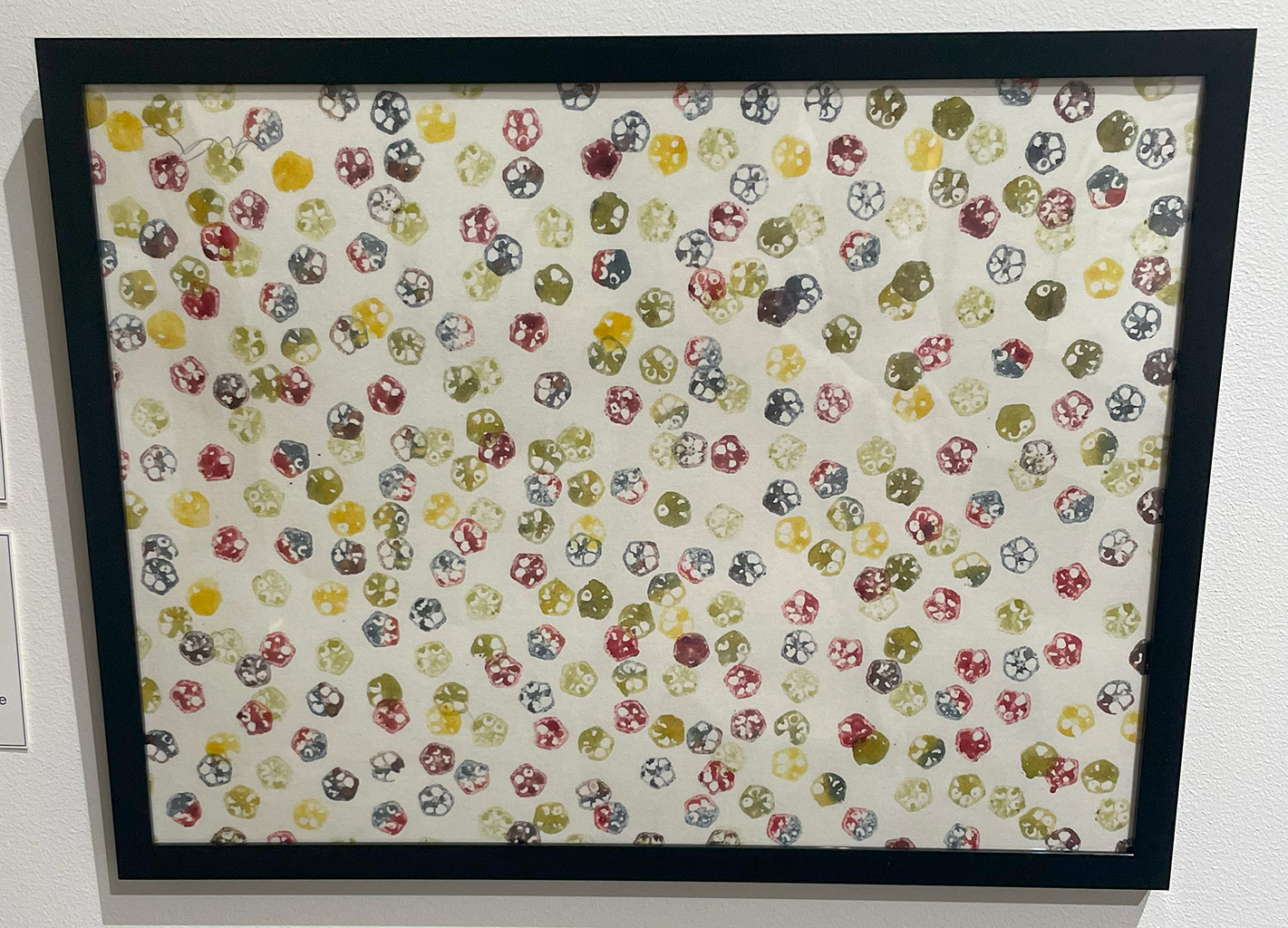

Le’Ecia Farmer – Okra Prints 1, 2023, botanical ink on paper

Le’Ecia Farmer is a queer Black parent currently based in Seattle, WA. She has studied fiber art (including weaving, basketry, natural dye, beading, and felting), visual art, apparel design, and mixed media in the Northwest, and traditional and contemporary textile printing in Ghana (Kumasi, Ntonso, Accra, etc.). She continually draws inspiration from the overt and covert connections between her cultural upbringing and art practice. Le’Ecia is keenly drawn to adornment and self-fashioning beyond surface-level connotations and plays with the various meanings that materials possess and views every medium as an opportunity to explore, experiment, or disrupt. Le’Ecia often engages with themes of diasporic longing, loss, and representation. She is drawn to materials like cotton, wool, raffia, natural dye, and vintage cloth and treats these materials as living and vibrating things. They carry our stories, as we do them. (Description courtesy of the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture)

Love this artist, so glad to hear more about her work and seeing recognition in the Black art Seattle scene.