Today, thirty-five years after the tragic demise of Vicious of a heroin overdose and many years after a media obsession with his life and death had ceased, things were about to get a reboot, 21st century-style. Teddie Dahlin was to find herself at the eye of the storm, a focus for fan forum and social media troll bile and paparazzi disruption and intrusion.

“Celebrity” as a Social Case Study

Within the academic study of celebrity culture, two approaches — the sociological and the semiotic — dominate. The sociological viewpoint is delineated as viewing the stars and the mechanism that creates them as the phenomenon; art and work is almost incidental and of no real importance. The semiotic approach reverses this premise, drawing on linguistic theories to read celebrities through the meanings attached to their work.

On a broader stage, celebrity culture exercises the minds of many others due to its effects and impact on the lives of ordinary individuals, and, in particular, upon children. Cudgels are taken up on this topic by a variety of people, from politicians, religious leaders and self-appointed shamans, to journalists, authors, bloggers and commentators. The language emanating from this discourse is often emotive, either speaking of the deleterious effect of celebrity culture on society, with its distorted image of the body and corrupting messages about wealth, sex and substance abuse, or blandly glorifying, adding to the cult, mythology and aura of the celebrity concerned.

Kirstine Harmon, the Assistant Director at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia, has identified that debates on the value and harm of celebrity culture occur in two forms: biography and social critique. Biography is, she states, “often a key player in the star system itself, written within the media machine that produces the stars themselves”. Conversely, social critique is more often prevalent in academic discourse.

Essentially, aside from its analysis or functional use, the maelstrom of celebrity is dehumanising, with intense press scrutiny, outlandish rumour and loss of privacy proving to be the quid pro quo for harnessing the media machine to promote and sell a person as product. Thirty years ago, analysis of new media revealed a mechanism that was primarily regressive in its attitudes – resistant to social change whilst reinforcing the predominant social attitudes and structures. In his book, Media, Gender and Identity, British sociologist and media theorist David Gauntlett supposes that nowadays, “It seems more appropriate to emphasize that, within limits, the mass media is a force for change.”

This shift, though a welcome force for change in societal attitudes towards sexuality and race, has however unleashed a more detailed and forensic approach to the lives of individuals who are either celebrities or connected to celebrities. The pursuit of stories, to feed a turbo charged social media and internet driven 24-hour news cycle, has led to a shedding of taboos. No subject is out of bounds, and old ideas of privacy and propriety are apparently redundant. However, whilst the dissolution of traditional mores seems to be encompassing within the notional realm of relative social attitudes promoted by these activities, at an individual level, this may not be the case. Indeed, there are countless stories of lives ruined by press intrusion. In the United Kingdom and the United States, there have been long-running high profile legal inquiries and, subsequently, prosecutions, due to the use of illegal phone hacking to gain inside information on a range of people, from major celebrities to what can only loosely be described “public figures”. Whether they are private individuals who are victims of personal tragedy whose mobile phone messages are intercepted, or A-list superstars whose intimate photographs have been stolen, the illegal hacking of private devices is an intrusion that does much to feed an image of overly powerful corporations who are able to ride rough shod over national laws.

Blurring the lines, the flag of public interest has been held up to justify these practices, in a process that envelops the innocent, both public and private, in the world of bright lights, telephoto lenses and door-stepping journalists that used to be reserved for fallen politicians and the very worst errant stars.

Teddie Dahlin & The Celebrity Machine

At the launch of Mathiesen’s Sex Pistols Exiled to Trondheim, Teddie Dahlin’s initial experiences were with press from her native country Norway, though as things gained momentum international fan forums got in on the act. Dahlin refused to allow the publishers to reveal her identity, opting — or so she thought — for anonymity. Unfortunately, two Norwegian journalists began to research her background. Dahlin’s family and life had been split between Norway and England, and the journalists’ trail led them to her aunt in England, various relatives and, eventually to Tore Lande, the original promoter of the Sex Pistols’ Norwegian tour, in his home in Malta. Friends were also approached, but none agreed to give interviews.

Some of the worst treatment, however, came from internet forums concerned with the landmark romance between Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen. “As soon as the book Sex Pistols Exiled came out, they ripped me to shreds and called me a liar,” says Dahlin. Numerous press articles began to circulate that gave untrue accounts and untrue stories relating to the situation between Dahlin and Vicious. It was then that she decided to take matters into her own hands and write a book about her Nordic romance with Vicious, “to set the record straight”.

This empowering decision was the beginning of an incredible journey for her. Dahlin not only wrote the book A Vicious Love Story: Remembering The Real Sid Vicious, to answer her critics, but established a successful new publishing company, with a roster of good emerging writers, and has written several more books herself.

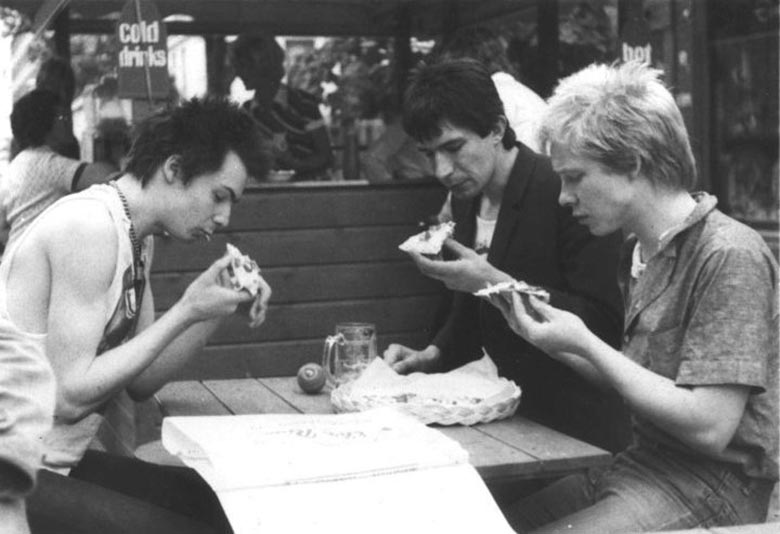

“Meanwhile, I was left alone on the sofa with the sleeping guy. He lay still for a while, and then suddenly opened his eyes and looked straight at me without moving a limb. He didn’t say anything to begin with, just stared, like he either suddenly didn’t know where he was or was trying to work out who I was. I ignored him, but it made me smile that he was watching me, very intently. After what felt like five minutes, but probably wasn’t that long, he smiled at me, warmly. I smiled back, but kept smoking, and tried to just look straight ahead and ignore him. He kept staring and I found myself smiling to myself, thinking him a little strange. He suddenly sat up and yawned.

“Can we share that?” he asked, pointing to my half-finished cigarette.

I handed him my cigarette and he thanked me, before taking a couple of drags and passing it back to me. I did the same and gave it to him again. I had heard about the Sex Pistols as a band, and Johnny Rotten being the vocalist and front man, but I had no idea who the sleeping chap was. To me, he was just one of the English guys and because he wasn’t outside being interviewed, I instantly assumed he was a roadie.”

A Vicious Love Story: Remembering the Real Sid Vicious – Teddie Dahlin – New Haven Publishing 2012

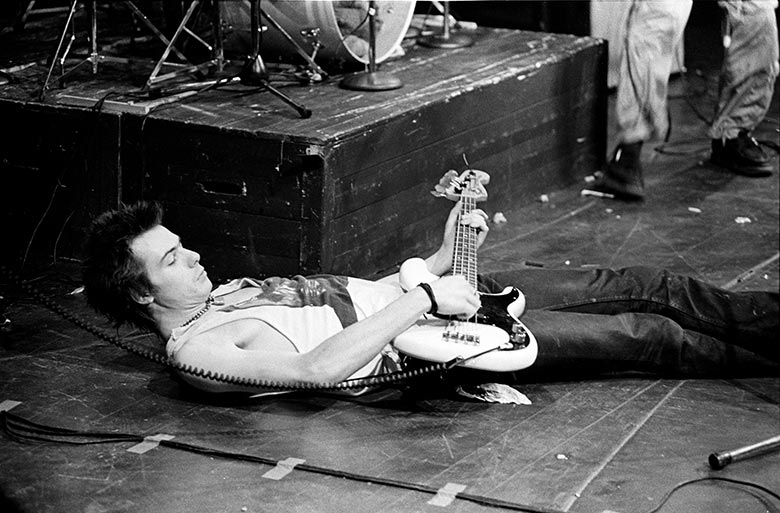

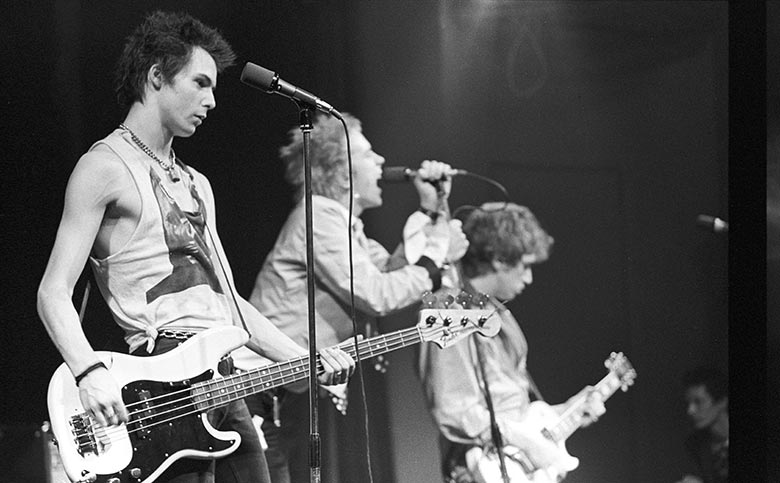

A Vicious Love Story: Remembering The Real Sid Vicious is not kiss and tell. There is nothing about what Sid Vicious was like in the sack and none of the lurid stories of drug-fueled craziness that became emblematic of Vicious in the press. Instead A Vicious Love Story attempts address the myth by detailing the human connection made between two teenagers. It is a story of shared cigarettes and soda pop, and of sneaking off to find food in a God-forsaken town in the middle of nowhere. Few, if any, rock music biographies attempt to achieve any intimacy with their subject, often instead falling for the myth that has enveloped their subject and relying on a paraphrasing that reinforces that which is already extant. In writing her book, Dahlin is unusual in that she is not and never was a fan of the Sex Pistols, or their music. It is this that may have allowed Dahlin the scope to give a personal and unique account of the man whose name was John Ritchie and who, in time, would be swallowed and then destroyed by the creation that was Sid Vicious.

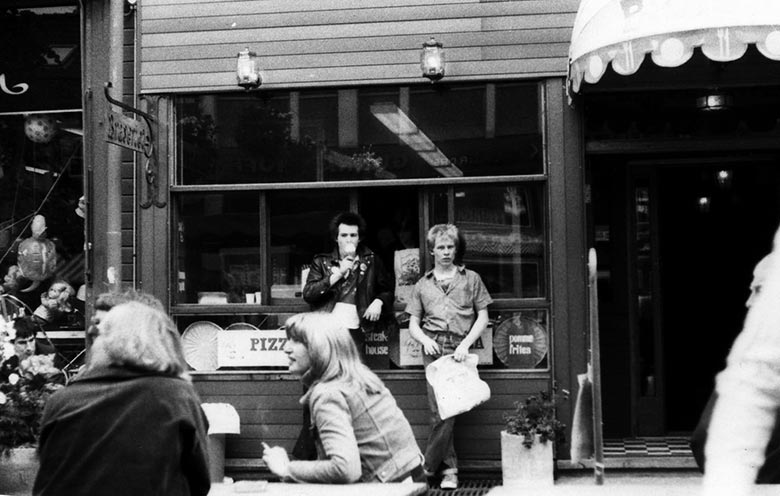

“I spent a great deal of time getting ready on Thursday, July 21st, 1977. I put a lot of thought into what I would wear. I wasn’t a punk and I didn’t want to come across as a wanna be rock chick either. I was sixteen and a half, and I was going to help out as a translator. At first I decided to put my hair up in a bun and wear a skirt, like a secretary. I wanted to look like Tore’s personal assistant, but I decided against it at the last minute, thinking I looked frumpy.

I wanted to be taken seriously, but vanity got the better of me. Although it was the middle of the summer and sunny, it wasn’t really hot, so I decided a thin, long sleeved, checked shirt would be okay. My hair was just below shoulder length, with blonde streaks from the summer sun. I used to put camomile in it before I went out in the sun to make it blonder. My hair was parted in the middle, with feathered cuts at the sides, which was much the rage at the time.”

A Vicious Love Story: Remembering the Real Sid Vicious – Teddie Dahlin – New Haven Publishing 2012

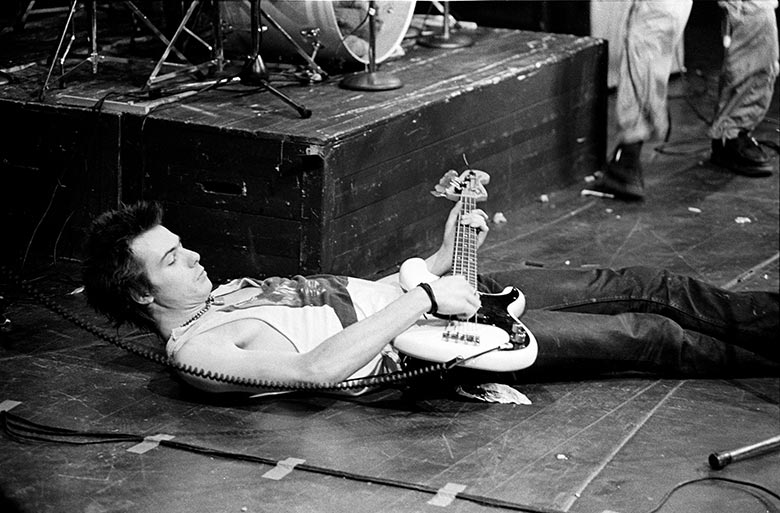

Perhaps Dahlin, with her jumpers, blond hair and small town ignorance of what was musically hot in 1977, was a temporary antidote to the world John Ritchie/Sid Vicious already knew. His mother was a heroin addict and, by the time the Pistols arrived in Norway, they had already attracted infamy and been subject to violent attacks from Teddy Boys. Whatever the situation, her book serves as a painful reminder that the pale, spikey-haired youth who, at the age of twenty-one-years-old, was accused of murdering his girlfriend Nancy Spungen, and who, less than four months later would be dead from an overdose, was just a normal kid.

At the time of her relationship with Vicious, Dahlin experienced a good deal more of the aggressive tactics of the press. Then, living at close quarters with the Pistols on their Scandinavian tour, she became part of the wider pandemonium and urgency to get the news. As she said recently, “They practically physically mugged me in the hotel lobby when I left the after party and decided to go back.”

In a world of hyperbole and star obsession, where disconnect between the consumer/fan and product/artist has grown ever greater, such a stance is both unusual and highly valuable. Beyond the veil, much of what occurs in the world of celebrity seems both controlled and contrived. The vogue is to cynically observe any antics as mere PR and image-shaping. If Miley Cyrus twerks or Justin Bieber drives his car too fast after having a drink, it is seen as a repositioning of their brand, to appeal to a fanbase that is heading into its teens. This may indeed be a correct assessment of the larger goals of the organisations that control our stars. However, behind the mythology and the layering of experiences, away from the drugs and the excess, there also lives a person — a person who is being sacrificed to our need for public interest and entertainment beyond creative endeavors.

The pursuit of Dahlin by the Norwegian press ended quite quickly, as their enquiries led them only to a wall of supportive friends who refused to give interviews or comments. She did face unpleasantness from online trolls and those who, obsessed with the darkness that will always surround Sid and Nancy, could not bear the idea that he might have been a nice guy. Her decision to write a book about her experiences was a brave one and has, for me, raised more questions than it answers, both about Sid Vicious and wider celebrity culture in general. There is no grand intellectual vision behind the story she told – no attempt to contextualise her experiences within the canon of critical theory, and no overt attempt to critique established impressions of Vicious. However, by dint of an honest approach, she has delivered a counterpoint to the received attitudes and prejudices that surround both Vicious and, more widely, the star circus that pervades all our lives these days.

Ω