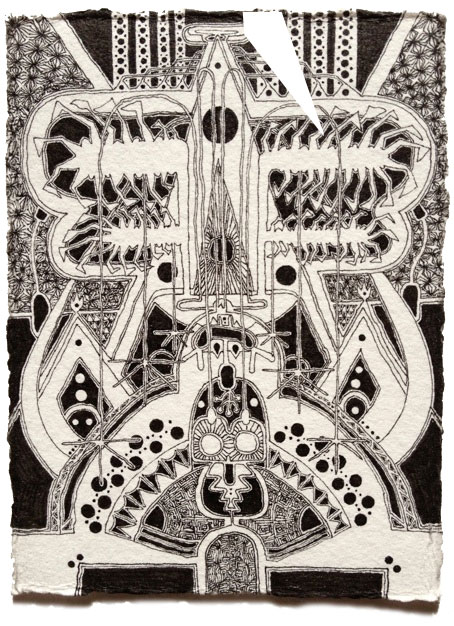

what was meant to be here was no longer, 2014, ink on industrial felt

what was meant to be here was no longer, 2014, ink on industrial felt

Inducing the Visions Through Body Movement

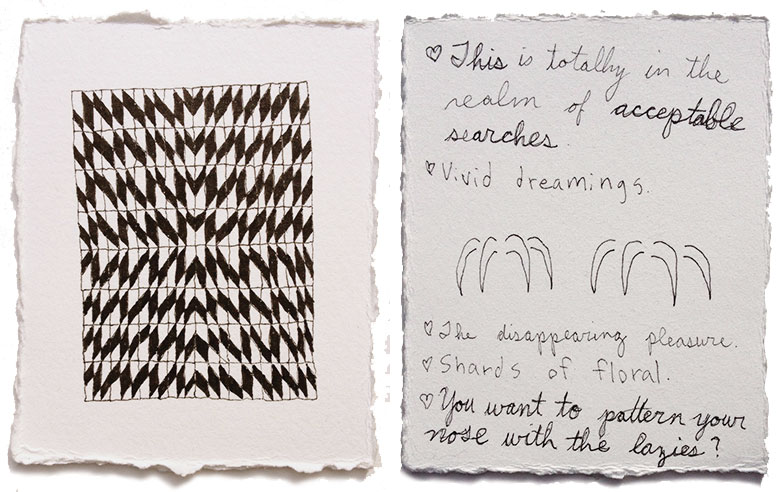

Hayden’s artistic style is one influenced by patterns and designs across a number of times, cultures, and walks of life – but how these influences are not always easily identifiable. Scrawled in nooks and crannies within Hayden’s loose and flowing linework are images that seem to reveal different reference points based on a viewer’s own experiences with history. Geometries pay homage to any number of cultures long, lost, or imagined, and within their hard edges and squiggly lines, some might discern floral motifs reminiscent of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics while others might see sci-fi blueprints for peculiar spaceships. The pattern bed from which Hayden draws is fertile, but his use of them is far from clearly plotted.

“Patterns are easy to find,” he says. “[It’s] harder to figure out which ones you want to use.”

While Hayden readily identifies Navajo rugs, the massive Bayeux Tapestry in France, and Aztec artwork as particularly influential, his methodology fortuitously removes a good portion of the “choice” for him.

“The way that I start working is — I dance an hour a day to ‘induce the visions’, as they say — just something that gets the blood going to the head,” Hayden reveals. Dancing is his main jump-off point for creation, but Hayden admits that any activity which gets the blood pumping will work, whether that be taking long walks in the mountains near his house or swimming in the waters near his hometown of Santa Barbara.

“I close my eyes after I dance really hard, and I let whatever comes to me come to me; I try to draw as quick as I can. I think that it’s a hallucinogenic state that’s very subtle that most people don’t pay a lot of attention to, but I think that most people have it,” explains Hayden. He goes on to describe similar mindstates that others have shared with them after they’ve had a long day at work and are just about to fall asleep.

Linking dance with his visual art practice was something that emerged naturally during a trip Hayden took to Europe years ago. After graduating with an MFA from UC Santa Barbara, he and his now-fiance and fellow artist, Hannah Vainstein, stayed in the English countryside where Vainstein had lived for four years. It was an idyllic period; they spent three weeks gorging on the small town’s abundance of fresh milk and cheese as well as celebrated blackberry season by making a blackberry apple cobbler nearly every other day.

As lovers of dance who had stuffed themselves to the brim with tasty treats, the two joked that they would tour Europe as a dance duo called Crumble Baby and the Mistress of Cosmic Crisp — “for the very reason that we liked crumbles”, according to Hayden. The two decided to bring an iPod and dance for an hour a day, no matter where they went around the continent.

“We started doing this and started sort of getting more and more into it,” Hayden recalls fondly, “and as I started to dance harder and harder, I found it was a really, really fertile time after I would dance for me to draw. The ideas and images would come really, really easily — so it became a part of my daily routine.”

Transference From the Earth

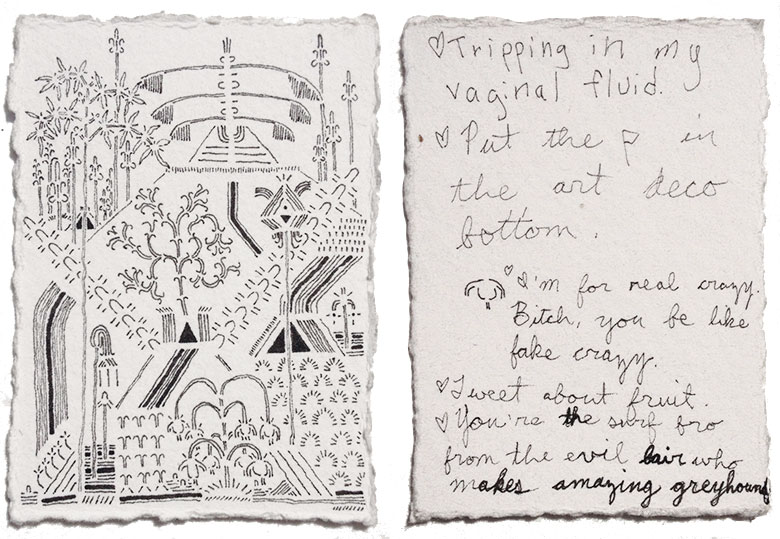

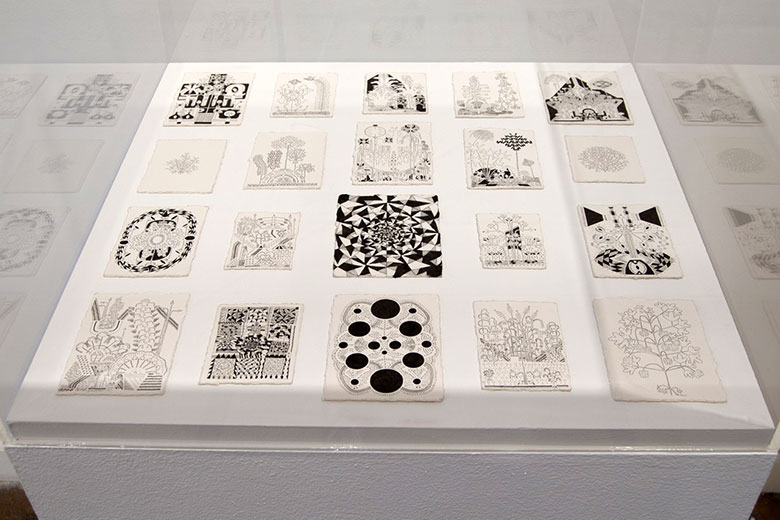

Not unlike a vessel for automatic writing, Hayden takes these dance-induced visions and scrawls them roughly onto small pieces of index card-sized paper, which he uses as mini soundboards for his ideas.

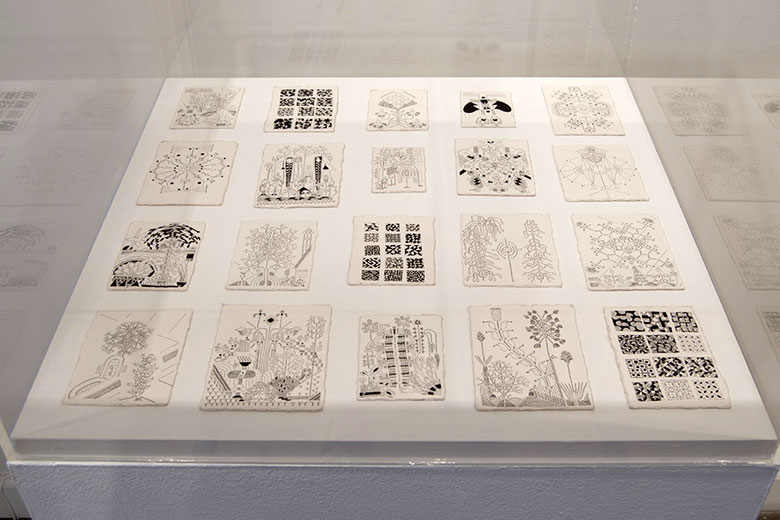

“I carry them with me everywhere I go, and that’s where I sort of put an idea as soon as I have it…” says Hayden, who will often have between five and twenty of the small card drawings going at once. Some of these cards are completed and some are not — and while all of the recent cards bear some similarity due to their use of blacks and whites, thin lines, and patterning, their styles are actually quite many and varied.

“I think it’s primarily gleaned from things that I look at in life sort of falling together,” explains Hayden.

– Nathan Hayden, on his small cards and related writings

It is perhaps this random coalescing of objects that leads to the difficulty of discerning Hayden’s visual references. Take, once again, what seem like obvious sci-fi references found in the spaceship-like technical drawings that appear throughout his work. Hayden does have some interest in sci-fi, but its influence is minimal to him at best; if anything, such parallels are actually more likely attributed to his exploratory childhood in West Virginia’s backwoods.

“For the first eight years of my life, I grew up in a really remote part of West Virginia; my parents were sort of ’70s ‘back to the land’-type people. They bought this little piece of land that was behind a state park; you had to walk a mile back in just to get to where we lived. Living out there, there weren’t a lot of kids to play with. I went out there to the woods and the nearby creek and was always messing around with insects and staring at different barks…” Hayden describes.

“My dad was interested in learning how to identify different things, so he taught me how to identify different trees by the bark, and different flowers; different plants you could eat in the wild… so I had an early interest in biology,” continues Hayden, “and I think that that sort of biological reference can look very sci-fi — but if you spend enough time in a creek bed, you’re going to come across things that are pretty science fiction-looking.”

expert team true believer, 2013, pen and ink on paper, 3 1/2 x 2 ½ inches

expert team true believer, 2013, pen and ink on paper, 3 1/2 x 2 ½ inches

One need only look to the plate drawings of biologists like Ernst Haeckel or stare at the forms sandwiched between microscope slides to realize that in the natural world, organisms can take on shapes that are plenty technical and mechanical. Hayden takes this type of naturalistic referencing one step further as well, through his use of materials and mediums. After returning from that trip to Europe, he began sourcing his own earth pigments by digging into the ground; he emerged with colors such as that from the plant wode, which creates the same blue that is referenced in Braveheart. Likewise, since his small cards contain the initial ideas that he synthesizes for more refined projects, Hayden decided to study them like a scientist, in order to find an analogous texture for his larger works.

“I looked at the [cotton] watercolor paper under a magnifying glass to see what its texture was like, and it’s actually little fibers that come together and look a lot like felt,” Hayden explains. After searching for a suitable source, Hayden came upon a company in Michigan which manufactures huge pieces of industrial wool felt, and asked them to sell him smaller pieces — which can still run up to five feet tall. Using a new material, however, has presented its challenges.

“The black and white ones are just ink — a shellac-based ink — and it’s a pain in the ass,” he says of these larger painted pieces. “Right now, they’re my least favorite things to make, because it’s a process that’s not too dissimilar to tattooing; it’s like a cross between painting and tattooing. I use brushes, but you’re kind of smashing the pigment into the felt, or the ink into the felt, because the felt is slightly water-resistant and the ink itself is water-based.”

Nonetheless, Hayden is so resolute on their feel and effect that he is learning new techniques in order to work with them.

Intersections of Personal & Global Histories

With his latest creations, a ceramics series loosely titled Shapes for Shadows, Hayden’s interest in earthly materials intersect with his personal visions and cultural anthropology in even more fascinating ways.

“I don’t even remember how I originally had the vision for the first ones, but I had wanted to work in clay for a while, because it’s, again, the sort of thing that you dig out of the earth,” explains Hayden, who loves how “forgiving” clay can be, as well as the potential of finding his own source for the material. In making these sculptures, Hayden is also finding a more solid alternative to his previous sculptures, which were made of wire and string.

“I just started making these objects that started coming to me, and later on, I discovered that they looked like ancient currency…” Hayden recalls. “I was flipping through a book of old clay objects and I forget what culture it was — but in this old Mesopotamian culture, they dug up this old little shapes that had holes in the middle, and a lot of mine have holes in the middle for various reasons…”

“They think these objects were maybe used for some sort of currency or an early alphabet of sorts,” he continues. “I found [that to be] an interesting way to think about them, especially since we sell our art for money — so there’s some sort of trade there — and it’s interesting to think about trading an ancient currency for a current currency.”

The way that happenstance and induced visions led Hayden to this age-old cultural practice makes it almost feel as though these inclinations are set deep within him, only to be let loose slowly through life discoveries. Even his practices in ritualistic dance seem to be an indicator of this.

“I think that it’s not even a new idea or anything to think about how many cultures danced for all types of things… they wanted rain, crops to grow well, bounty, fertility, the list goes on forever and ever…” says Hayden. “I think that moving your body and your brain sort of syncs up with that. It’s a really powerful way to bring things into the world.”

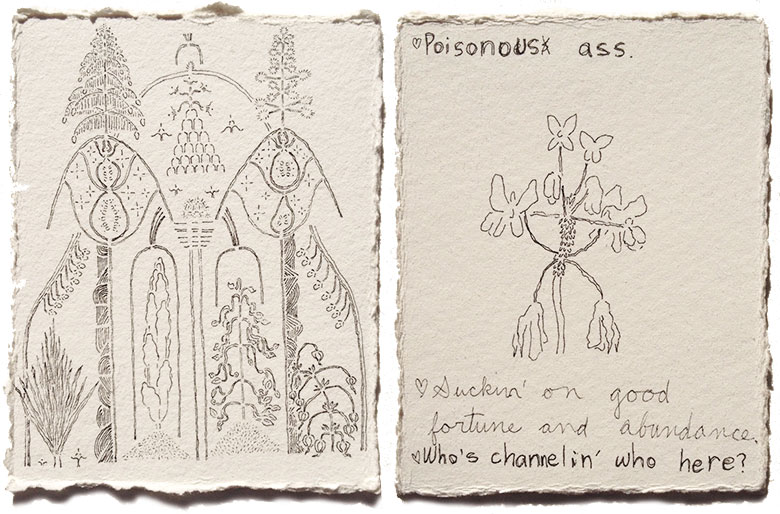

just because you talk the talk doesn’t mean your molecules are shifting, 2013, pen and ink on paper, 3 1/2 x 2 ½ inches

embracing the dark, 2012, pen and ink on paper, 3 1/2 x 2 ½ inches

embracing the dark, 2012, pen and ink on paper, 3 1/2 x 2 ½ inches

Analyzing and synthesizing the knowledge of yore into modern creative practices is natural for Hayden, as is giving powerful events from his life — such as his trip to Europe and his childhood spent in nature — their due credit. Nonetheless, there are aspects of Hayden’s work and life where, like the patterns in his art, influences can’t exactly be traced with much clarity.

“Since I was little, I was always making, drawings and objects that had a psychedelic nature to them — so I feel like when I ate psychedelics in my early 20s, it was kind of a verification that what I was doing was there, just given more confidence, maybe. I don’t know that I would be making the same thing I I’d never encountered psychedelics, but I might be making something along the same lines,” Hayden muses. “It’s really hard to tell; you can’t really separate all these things out. I feel like if you eat mushrooms or whatever, that sort of becomes part of you and part of your lexicon, so I can’t say that it hasn’t influenced me, but I’m not sure exactly how it has influenced me, either.”

Yet part of the beauty of Hayden’s type of art — which truly gets pulled out of the ether to become manifest in the real world — is that its influence can be significant and feel significant, even if its influence is not consciously elaborated upon.

“I’m just trying to access the possibilities of other things –” Hayden explains, “– and in the same way that I look at art throughout history and nature for little pieces of those other realms, I’m hoping that I can be a part of that process and for people to get a peek into other realms by looking at my stuff, that might bring about stuff that I can’t even imagine.”

Hayden will be the first to admit that hoping for such an influence might be lofty — “a lot of people, I think, don’t really even really look at the work,” he comments — and so, he understands that sharing his own experiences might be an even more important and direct way to supplement the viewing experiences of his art.

“Maybe it’s better for me to tell stories about encountering things that I didn’t realize would affect me so profoundly until later,” he speculates. “When I was a little kid and I was out in nature, I just thought it was fucking boring because there were no other kids to play with… but now, I realize that I don’t think I would even be making art if I hadn’t had years with nothing to do except stare at nature.”

Ω

www.nathan-hayden.com

[…] wool felt and are painted with pigment he makes himself. In an interview in the online magazine, Redefine, he has described the application of pigment as being a cross of tattooing and painting: the […]