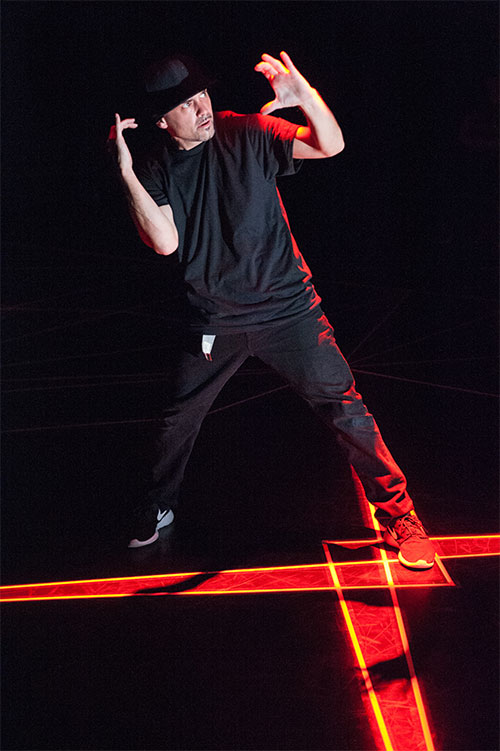

Photography and Opposing Forces PR shot by Gabriel Bienczycki

Photography and Opposing Forces PR shot by Gabriel Bienczycki

“Join the dance party!” calls the high-energy soundtrack, in an attempt to liberate viewers from the sticky intimidation often thrust forth by modern dance performances. Naturally, plenty chose not to heed the call and remained perched on the surrounding high school bleachers — but bolder members of the audience stepped onto center stage, shaking and shimmying alongside seasoned dancers like O’Neal, the company of Opposing Forces, and what seemed like a larger number of their collective movement-oriented friends. This opening antic was an informal way to raise levity, while also hinting that the performance would be more than just pure entertainment; it also has a social message to bear.

Initially popularized by youth and street gangs in the South Bronx, the male-dominated art of breakdancing has been competitive since its inception. The “battles” which are central to the form have their roots in turf wars and machismo, and as such, toughness remains core to the practice. While the landscape has evolved over time and females are present in some circles, breakdancers are still called out regularly for dancing too “soft”, and many fluid movements are still associated with the female sex.

With Opposing Forces, Amy O’Neal, who is equally well-versed in hip-hop and contemporary dance, has coordinated a clever study of gender roles, by intimately exploring “femininity” through the eyes of five male breakdancers who she teaches to move within the contemporary dance realm.

(Right) Fever One of Rocksteady Crew in performance of Opposing Forces. Photography by Bruce Tom

When formulating the piece, O’Neal was presumably cognizant of the less streetwise spaces in which the work would likely be performed, and for the unacquainted, she smartly conveys some knowledge through the structure of the piece, which was carefully calculated and determined before the movements themselves were. Included are routines that serve as quick primers to classic hip-hop dance movements as well as breakdancing fundamentals, the latter of which showcases each dancer’s style individually.

When formulating the piece, O’Neal was presumably cognizant of the less streetwise spaces in which the work would likely be performed, and for the unacquainted, she smartly conveys some knowledge through the structure of the piece, which was carefully calculated and determined before the movements themselves were. Included are routines that serve as quick primers to classic hip-hop dance movements as well as breakdancing fundamentals, the latter of which showcases each dancer’s style individually.

Hence, when interview snippets begin to play during each dancer’s solo, and each one describes how masculine or feminine he perceives himself to be, viewers intuitively draw patterns between which movements might be considered “feminine” and which might be considered “masculine”. These soundbites are subtle and tasteful, but somehow manage to lodge into one’s mind, framing the remainder of the viewing. Fever One, perhaps the fastest and most aggressive of the bunch, self-identifies as rather masculine, while Mike O’Neal’s slower and more fluid movements seem in line with his more neutral assessment of himself. As choreographer Amy O’Neal helps the dancers fuse their strengths with contemporary dance, viewers can’t help but dissect whether or not each dancer’s self-analysis is accurate, as well as how that perception of self shifts throughout the piece.

The process of merging such disparate dance styles is not nearly as simple as it seems, particularly when technical language is not the only limitation. Coordinating Opposing Forces was a psychologically-dense affair. Although choreographed movements are fairly commonplace in breakdancing, the style lacks the intimacy found in contemporary dance, and training the dancers to move outside of their personal spaces was a very real challenge. Social stigma is also serves as a method of control within such circles. O’Neal and the dancers had to explore new movements by overcoming ingrained fears of hurting their reputations while reassessing their relationships to masculinity.

As Alfredo “Free” Vergara of Circle of Fire and SoulShifters explains in the introductory documentary for the series, “There are certain dance styles that are definitely more feminine than others, and part of my uncomfortability was like, ‘I don’t want to dance like that, because to me, it would feel not right for me to dance that way.’ For one, I don’t know the technique, and it’s just not something that I do.'”

Despite the fact that the five main dancers of Opposing Forces — which also include Brysen “Just Be” Angeles of Massive Monkees and Mozes Lateef Saleem of Circle of Fire and SoulShifters — have known each other for years, it wasn’t until O’Neal worked with them that they experienced more direct physical contact with one another. In the latter half of Opposing Forces, the men can be seen holding hands for extended routines, stacking in and out of one another like dominoes, or swapping interlocking body parts like puzzle pieces. These points of connection work in contrast to the earlier scenes, wherein the isolation of one’s personal craft played a larger role. O’Neal speaks simply of the difference in breakdancing, commercial dance, and contemporary dance, saying, “Movement within those environments have very different contexts and meanings; there’s very different rules.” Opposing Forces bends those rules into an amalgam which has rarely been seen.

Opposing Forces performance shot by Bruce Tom

Opposing Forces performance shot by Bruce Tom

The production quality of Opposing Forces must also be credited. O’Neal’s choreography is certainly heightened by the skills of every dancer, put perhaps just as much by the excellent sound design of Waylon Dungan, aka WD4D and the geometric floor and wall designs by Ben Zamora, which work hand-in-hand with the incredible lighting design of Amiya Brown. Use of darkness and light is exquisite throughout the piece, at times creating an ambient haze, and at times segmenting off certain shapes to accomodate solo routines, two-person dances, or other challenging configurations.

Opposing Forces is a damned important work — but its one major drawback may be that addressing gender issues almost always feels a bit heavy-handed in the 21st century, regardless of the medium or format. The male-dominated company also inevitably raises the question: in a piece that is exploring femininity within breakdancing culture, why is the female presence so sorely lacking?

Yet, as with everything else in the production, the decision to use primarily male dancers has been considered through and through; it is very, very intentional. Feminist dance teams, writing groups, literary magazines, rock concerts, and the like have long been fighting for equality — but one could argue that the work that females need to do for feminism has already reached a point of saturation, to the degree where having the word “feminist” precede a gathering can read a bit like a boring cliché. In order for deeper degrees of change to happen, the other party — the male party — need be enlisted as a compatriot in the fight, and that is exactly what Opposing Forces attempts to do.

“I really started realizing as we were talking about it… just the national conversations that are going on around race and men and feminism,” O’Neal explains in the Opposing Forces documentary. “… It was the right moment, because of what’s going on around stereotypes around men of color, and also around the conversation of, ‘What is feminism now and how do we bring everybody to the table? If it is really about the equality of the sexes, how do we involve everyone in the conversation?'”

Opposing Forces Documentary

Directed by Kyle Seago

Featuring:

Concept, Direction and Choreography: Amy O’Neal

Performers and Movement Collaborators: Alfredo “Free” Vergara (Circle of Fire/SoulShifters), Brysen “Just Be” Angeles (Massive Monkees), Fever One (Rocksteady Crew), Mike O’Neal (Chpt1/BeatHippies), and Mozes Lateef Saleem (Circle of Fire/SoulShifters)

Original Score By: Waylon Dungan aka WD4D

Vocal Performance on cover of Kendrick Lamar’s Backseat Freestyle: Gifted Gab

Lighting Design: Amiya Brown

Floor + Wall Design: Ben Zamora

Costume Styling: Wazhma Samizay + Daniel Hellman with Bobojan

Management: Stefanie Karlin + SQUID MGMT

Ω