You will never be lovelier than you are now.

We will never be here again.”

– Homer, The Iliad

All too often, apocalyptic films foretell the coming of the end in the form of big blowouts rather than a slow dismantling. In the overly-Hollywood 2012, buildings collapse and helicopters fall from the sky for no seemingly reason whatsoever. In War Of The Worlds and Independence Day, intergalactic monsters take over, causing environmental catastrophe and obliterating all that human beings hold dear. Gripping as those examples may be, there are times when the macro observation of a situation may not be the most interesting story. In the face of some real human catastrophes, as in 9/11 or Columbine, hurricanes or typhoons, the personal narratives that emerge — often long after the fact — can sometimes be even more fascinating. And it is from those closer looks that film like H. focuses its attention, encouraging viewers to slow down even as the world of Troy, New York, is crumbling around them.

All too often, apocalyptic films foretell the coming of the end in the form of big blowouts rather than a slow dismantling. In the overly-Hollywood 2012, buildings collapse and helicopters fall from the sky for no seemingly reason whatsoever. In War Of The Worlds and Independence Day, intergalactic monsters take over, causing environmental catastrophe and obliterating all that human beings hold dear. Gripping as those examples may be, there are times when the macro observation of a situation may not be the most interesting story. In the face of some real human catastrophes, as in 9/11 or Columbine, hurricanes or typhoons, the personal narratives that emerge — often long after the fact — can sometimes be even more fascinating. And it is from those closer looks that film like H. focuses its attention, encouraging viewers to slow down even as the world of Troy, New York, is crumbling around them.

H. begins by peering intimately into the lives of an elderly couple. Their relationship is one of typical habitual dysfunction; love is not the primary motivator of their interactions, but creature comforts and concretely-defined roles for each individual. Helen — of Troy, indeed — is obsessed with her “reborn doll” son, which is a life-like manufactured baby doll which she feeds at regular intervals, brings to the supermarket, and even occasionally nurses with her aged breast. Her husband, Roy, spends his time fielding his wife’s nagging calls and hides out in the bathroom to be alone. In a drunken state, he guiltily admits to his friend that he has recently fantasized about how free he would feel if his wife were to suddenly pass away — and it is with this type of interaction that H. builds its tone. All might be coming to an end, individually, regionally, or globally, but that end is a slow crawl, not a sudden implosion. As a meteor-like object hits the city, H. focuses not on the meteor strike itself, but on details of the fallout. Newscasts and gentle observations hint that time and physics have shifted almost imperceptibly, and human interactions are thusly influenced. H. progresses by using sound design and image manipulation to help supplement an increasingly psychedelic reveal of the Troy’s newest mysteries. Mirroring the relationship of Helen and Roy, end of the world seems not to come in the form of a raging war, but in the slow trickling out of life.

When H. later introduces another couple, we discover that the young woman is the film’s second Helen of Troy, and that this couple, though much younger and with much more passion, is no less dysfunctional. Once again, their interactions offer a parallel to the slow dismantling of the world around them, and it is really through their eyes that viewers really note how Troy has begun to change. As mysteries descend like a thick fog, they find themselves being lulled to sleep at regular intervals, awakening with no recollection of how long they had slept. Long-understood rules of physics corrode and become as malleable as clay: coffee leaks out of glass cups, keychains fall off of metal hooks, and water flows backwards from taps, to the confused amazement of all who witness the phenomena. All these small details, though, are just a lead-in to the bigger questions: who else is affected, and what crashed to Earth? Why are people disappearing suddenly, and are their disappearances self-appointed or governed by some external force?

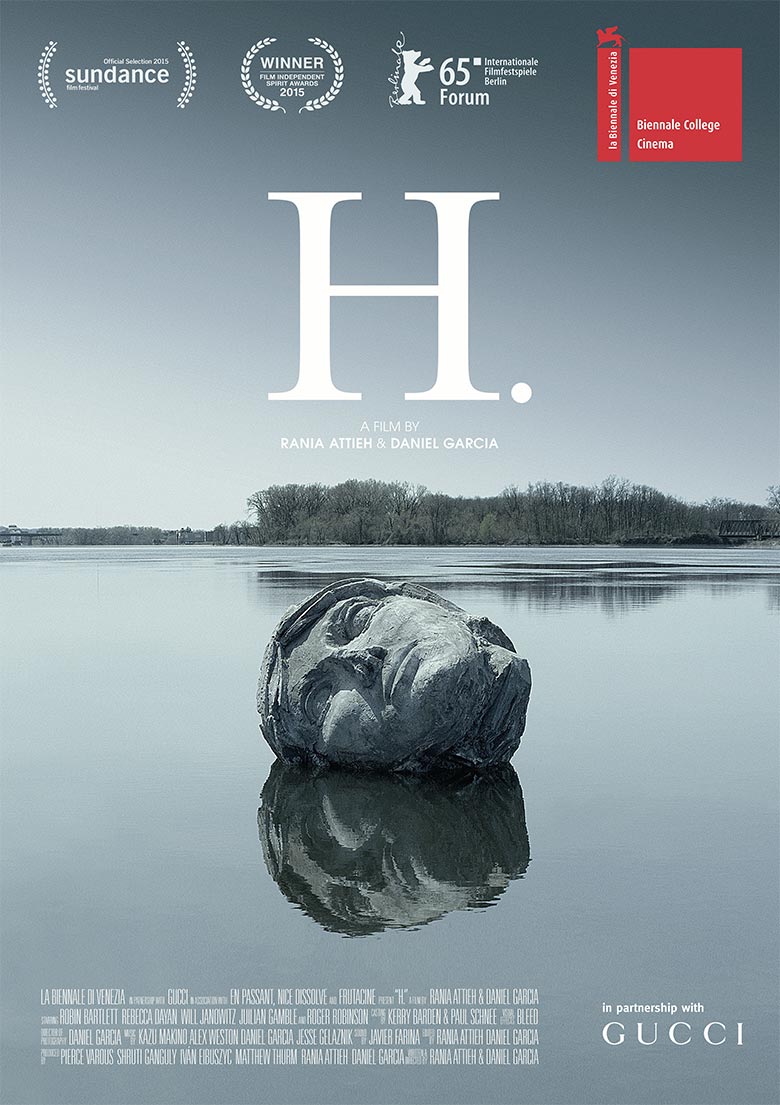

Indeed, H. offers up much for viewers to contemplate, but it is at the artful philosophical level that the screenwriting, editing, and directing duo of Rania Attieh and Daniel Garcia really start manifesting the eyebrow-raising, head-scratching details. Yes, there are two Helen of Troys, and broken Roman statues are seen floating downriver; quotes about The Iliad bookend the film, and black mares appear and disappear like fever dream visions. One assumes that all of these symbols hold latent meaning for the filmmakers, yet their significance are far from easy to discern. But what remains, through all the snail-paced reveals of human idiosyncrasies, is that H. is a successful, minimal experiment in sci-fi, and it beckons for a repeat viewing just as soon as it ends.

Ω