“I had a big manifesto of ‘no’s’ at the beginning, [of things] that I didn’t want to do.”

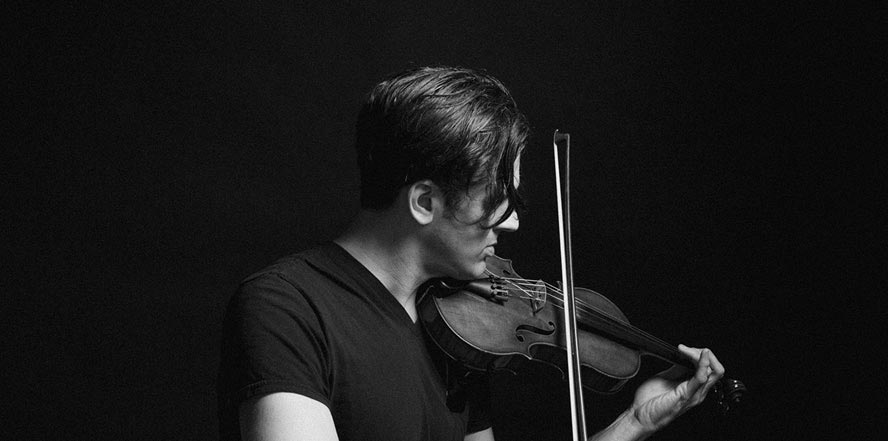

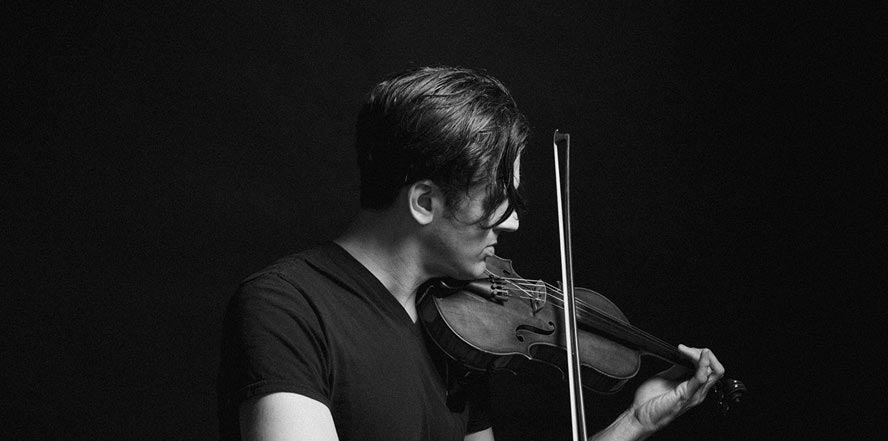

As a composer, violinist, and multi-instrumentalist, Christopher Tignor has, since the early ’00s, led the New York City-based instrumental groups Slow Six and Wires.Under.Tension. Up until recently, however, he’d had little interest in playing solo, and figuring out a way to do it that would hold his interest began with formulating a list of what he didn’t want to do. That eventually guided him toward his latest solo album, Along a Vanishing Plane.

For one, Tignor didn’t want to play to a click track; he didn’t want any of the “prepackaged, canned stuff.” What he wanted to make was something full-range — not thin in terms of orchestration.

“So that posed an interesting challenge,” he explains. “I thought about what that would mean, to be able to do all those things as one human being, while not just relying on some spacebar rock type implementation. It became a real exploration of what could be done, and what you want to do, as one person.”

In response, Tignor was forced to do a lot of soul-searching, which he feels directly colored the effect of the music.

“It’s very different to write music for yourself… than it is for an ensemble,” he continues. “You really have to decide what kind of person you want to be on stage, which is sort of the same thing as saying, for me at least — because I’m not an actor and I’m not trying to… evoke a person onstage — the question becomes, ‘What kind of person do you want to be in general?'”

“It was, in some ways for me, a surprisingly gratifying trip,” Tignor continues.

Constructing Solutions

Central to the process of writing Along a Vanishing Plane was figuring out a way to create more sound than one person might normally make, without resorting to using “backing karaoke”. Tignor achieved this through his talents as a software engineer.

The software programs he has created — Super Conductor, Trigger Finger, and Five Finger Discount — are in fact free and readily available on his website, and all run inside Ableton Live.

Trigger Finger, for example, is a drum trigger that allows the user to map a drum kick signal to a score that will iterate through a series of MIDI pitches.

“It’s sort of equivalent to playing a synthesizer key, but with your foot, and instead of choosing the pitch by pressing a different key, there’s one key,” Tignor explains.

There’s also an aspect related to the violin. Tignor plays his violin through a series of harmonizers that he has restricted to playing specific notes from a specific scale which he can change on the fly. The underlying idea for the technology came to Tignor after he studied how Estonian composer Arvo Pärt constructed his renowned Tintinnabuli compositional style.

“He actually uses a very specific orientation of notes between his upper voices and his lower voices which can be described algorithmically, and I realized that I could actually do that live with the violin, just by defining exactly which pitches would be created from my original violin sound.”

Tignor’s software starts with the notion of that kind of specific harmony and takes it in his own direction. The devices he came up with for Along a Vanishing Plane are specific to the album, and both the tools and the music were created together, which made for a two-year endeavor. Almost all of Tignor’s major musical projects have involved coming up with new software, though he says he’s gotten a bit better at trying to reuse things.

“It’s definitely part of the artistic output — making these pieces of music software which are bound to ways of thinking about music, and ways of being a musician. Specifically a live musician,” he adds, “because I have a very narrow interest in electronic music, and it’s pretty narrowly focused on what you can do live.”

Going Beyond Perceived Limitations

Along a Vanishing Plane is an absorbing listening experience, and it’s even more remarkable to see it performed. With little more than a violin, tuning fork, kick drum, and some electronic equipment, Tignor conjures layered compositions that exude the depth of a chamber ensemble schooled on the classics but speak to modern tensions.

After playing some shows leading up to the recording of the album, Tignor noticed how audiences were noticeably responsive to the element of watching “one man put this stuff together.” Subsequently, he decided to capture the songs on video as he was playing them for the record, so that Along a Vanishing Plane would also be available as a ‘video album’.

“A video isn’t a live show obviously, but these recordings do evoke the live aspect of it. You can see what’s going on, you can see me doing it. That was always part of my idea for the music…” he says. “Pretty early on, I started toying with the idea, and eventually I started thinking, ‘Let’s just go all the way and try to make this thing a video album’, as opposed to, ‘Let’s just record a few tracks’.”

For Tignor, the most meaningful aspect of this process is how it demonstrates that one person with an idea and a bit of elbow grease can make something that transcends the perceived limits of what he or she is working with. He considers it a way to “get beyond where we’re at” — which for him specifically is being one person up on stage trying to hold down numerous forces.

“You can apply that approach to so many different things in life; this is just my musical bent on that,” he explains. “It’s all about: there’s a compelling musical thing to be done; let’s sit down and think about how it can be done in a way that’s gratifying.”

Flexing Time

The songs on Along a Vanishing Plane were significantly affected by the results of repeated live performances. “I’m a constant reviser,” Tignor observes. “I think editing is the most valuable skill any artist can have, and I do a lot of that. I’ll drop stuff; I’ll remove whole sections. I’d say probably 90% of the music I write never makes it to the stage, and the stuff that makes it to the stage gets pretty well revised, for sure.”

Flexibility was also important not just to the structure of the material, but to its sense of time as well, as Tignor describes tie to be “super critical” to his music.

“Let’s just take one tangible question: how would I have recorded this music with overdubs? There’s so much space in this music that I’m not sure, [even] with enough practice I’d be able to catch all the entrances.”

This music, he says, relies on a sort of temporal flexibility that is one of its most expressive components. It is affected by everything from the nuance of the performer as an individual to how the room sounds, illustrating a fundamental difference between the nature of witnessing a live performance and listening to a standard studio recording.

“You could compare that to most popular music,” he continues, “where that’s not critical… That’s a listening experience that really sort of benefits from that predictability, and that sort-of codified structure. But that type of thing works at odds with what I’ve been trying to do on this record, and I think you can hear that tangibly in the music.”

Asked if Along a Vanishing Plane is almost a live album, Tignor admits that it could be in a certain sense.

“I mean, it’s not a live album in the sense that it’s certainly edited, but of course, it’s edited between very, very big sections,” says Tignor. “So I’d say it’s as live as, like, when Louis C.K. puts out a special on Netflix. Obviously, it’s edited over a few nights.”

“I think people resonate with that live quality. I don’t think people want you to play sound files at them at shows. I think that’s something people are used to now, but I think people respond palpably when they know that decisions are being made musically on stage, as part of the process that they’re in. It invites the listener into the experience. They’re not invited into the experience when you were in the recording studio a month ago when you made the backing track,” Tignor continues.

“The point is about bringing people in to the ritual, and you do that by keeping things truly live. Which is to say, keeping the major musical choices in the room with them.”

A Departure From its Past

The degree to which music can be affected not just by being performed live in front of a given audience, but by the particular nature of the room itself in which that music is performed, is something that Tignor has had a fair share of experience with. He began pursuing sound engineering in college, and wound up doing sound at two legendary New York City clubs, CBGB’s and Brownies. Before that, he studied at Bard University, with music technology innovator Bob Bielecki, and for a time, worked with pioneering minimalist La Monte Young as an artist assistant. He also became involved early on with the Music at the Anthology Festival (MATA), which was founded by Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, and Eleonor Sandresky.

“I got sucked into that scene and that festival pretty early on in its inception and ended up doing it for like eight or nine years,” Tignor recalls, “and eventually I became the technical director. So I got to hear a lot of amazing, of course, cutting edge new music, while I was simultaneously working sound at CBGB’s, and then later after that Brownies… sort of the rock side of things.”

Holding those credentials in both the avant-garde realm and the downtown rock scene, Tignor formed Slow Six at the turn of the ’00s. The group’s classically informed experimental post rock wasn’t entirely without its peers, but was at least a step or two ahead of its era.

“When Slow Six was starting out. we were complete freaks. We’d show up at these rock clubs with seven music stands, a string ensemble, two electric guitars, a Fender Rhodes and a video projector which we’d set up… and play these thirty-minute-long composed pieces that were all scored,” Tignor recalls.

“Not to mention, at that point, I was bringing down a desktop computer for every show because… the laptop power [back then] was not nearly enough to do live processing. So it was like total insanity. And of course we’d be on the same bill with normal rock bands or whatever, because that’s what you do; you just play next to whoever you get on with when you’re starting out,” he adds.

“I think in some ways, the novelty of it was part of the charm. I think it really did allow us to set a trend in New York for this so-called crossover thing which seems to be ubiquitous now, but it was very novel at the time, and it came from a very sincere place for us.”

Instead of trying to get Slow Six into upscale venues like Merkin Concert Hall, which he felt didn’t fit the vibe of their music, Tignor found it very rewarding to ‘reclaim’ the traditional rock clubs the group played in, and “transform them through a new listening experience.” Slow Six was set aside after a decade and three albums together, and Tignor, along with drummer Theo Metz, began Wires.Under.Tension, whose style was more spry but no less experimental. The duo released two albums, Light Science (2011) and Replicant (2012) — and prior to that, Tignor put out records under his own name, stating in 2009 with Core Memory Unwound. His 2014 album, Thunder Lay Down in the Heart, featured collaborations with Pulitzer prize winning poet John Ashbery and pianist Rachel Grimes, formerly of Louisville legends Rachel’s.

Along a Vanishing Plane, though, presents something different than its predecessors: a one-man modernist chamber ensemble built on the benefits of technology while also evading its limitations.

Despite his own experiences with having a foot on each side of the divide between classical and pop music, Tignor thinks the suggestion that the wall between them is more permeable now than ever before isn’t quite accurate.

“I don’t think there’s ever been anything fluid between those worlds,” he says. “I think there’s a very asymmetric referencing from the world of so-called ‘indie classical’ these days to the credibility of popular music… Of course, there’s real sincerity there in the sense that these young composers really do value all that music, but I think there’s also a large degree of ‘Where the fuck are our audiences going?’, and it’s a bit of an advertising rhetoric, you know.”

Acknowledging that collaborations between indie and classical musicians are definitely more of trend now than they were back in the day, Tignor feels that the musical values that people in the art music world have “are in many ways fundamentally different than what goes down in the practice room when you’re putting rock songs together for some of the big bands that are running around Brooklyn right now.”

Perhaps, though, those musicians who wish to chart a path between those two orbits in their own work would do well to look to what Tignor has achieved both with his previous bands as well as his more recent solo work. The ideas behind Slow Six’s big moments, the agile cycles of Wires.Under.Tension, and the natural grace of Along a Vanishing Plane, are well-communicated, but the music’s accessibility reaches beyond any need to understand those concepts.

Before finding his path in music, Tignor’s ambitions were literary. “That was sort of my initial model for how to be an artist, you know,” he says, “and my idea, still, for how to be an artist is how to be a writer.”

Tellingly, he goes on to explain how he thinks when it comes to how to be an artist, writers have gotten it right where others haven’t.

“I mean: you should write every day. The greatest works of literature are accessible by anyone, and they do not need to compromise on their ideas in order to do that. There are no extra points for being syntactically opaque like there are in many forms of high art [and] high musical art,” he says. “For example, you could be on the train reading Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, or The Brothers Karamazov, or whatever… You don’t need any special training to be doing this, you just need a will and an interest, and maybe some artistic inclination, or whatever it is, to reach out toward that human connection. That’s a really amazing prospect. That is far less the case for a lot of other forms of art.”

Ω