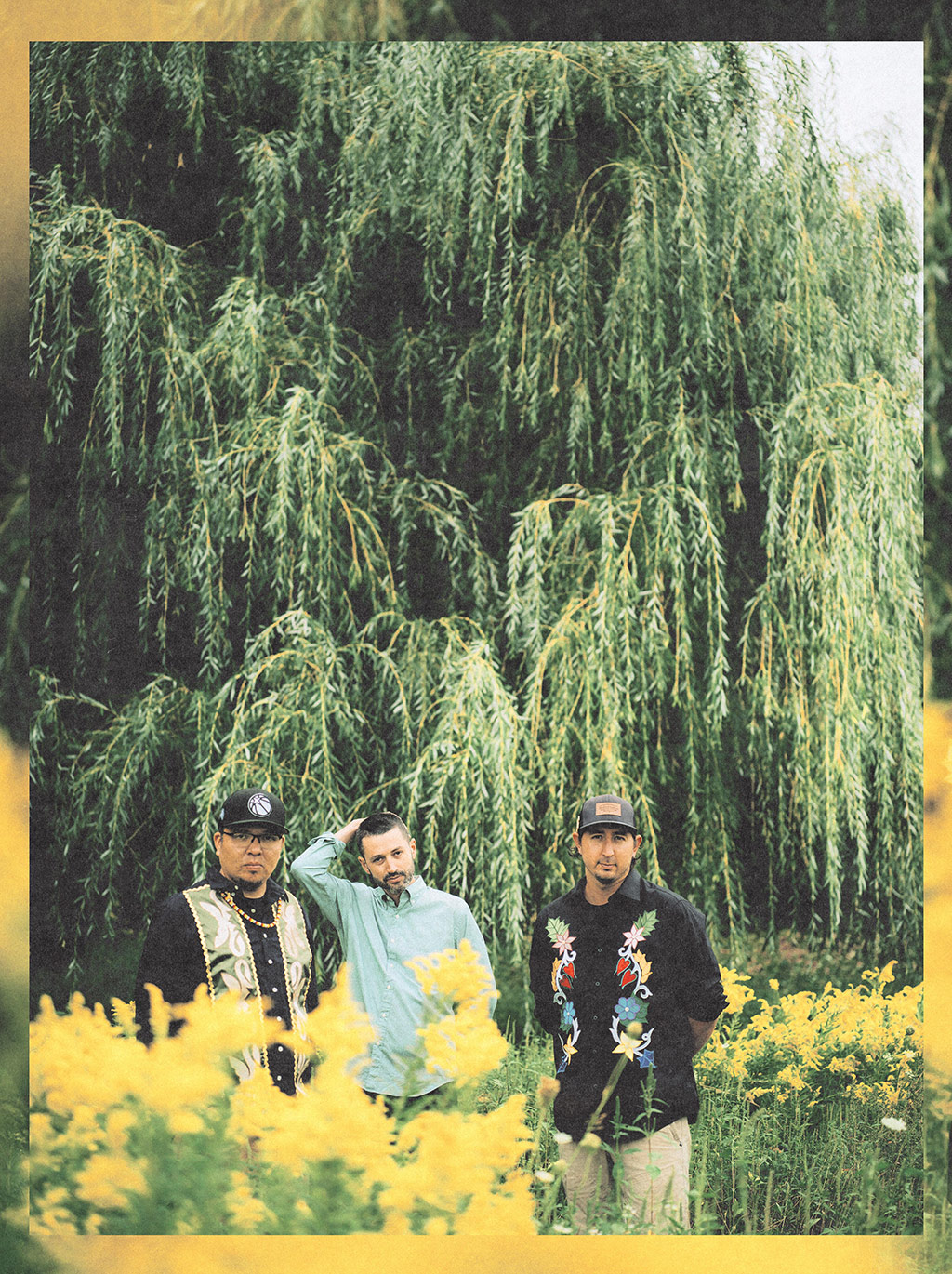

Band photos by Graham Tolbert

Collaboration as a Natural Movement

Bizhiki may be primarily centered around Jennings, Rainey, and Carey, but it also pulls in a number of guests — such as vocalist Mike Sullivan (Lac Courte Oreilles) and producer Brian Joseph — who are regular collaborators with Bon Iver and their numerous related offshoots. Each of Unbound‘s 11 tracks seamlessly blends stylistic lines in a way that listeners might expect from what Rainey affectionately calls the “Bon Iver Music Family Tree.”

Such staple sounds include sexy saxophones, pensive slide guitar, simultaneously smooth and highly affected vocals, and electronic experimentations that come and go. Yet what makes Bizhiki unique is its inclusion of powwow vocals and drums informed by the ceremonies, which are then layered throughout the record in dynamic ways.

Bizhiki can point to its early origins at the Eaux Claires Music Festival, which was founded in 2015 by The National’s Aaron Dessner and Bon Iver frontman Justin Vernon. The festival, located in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, did not feel comfortable hosting the second estival on Ojibwe homelands without meaningfully representing the Indigenous caretakers of the area. By Rainey’s telling, Bizhiki was born through a “natural movement,” where little ever felt forced.

“We were asked to open up for people in a most respectful way — meaning they weren’t asking us to do something that was out of our comfort zone,” Rainey explains to REDEFINE. “That comfortable blanket… was always there with the Bon Iver Music Family Tree.”

In Bizhiki’s press release, Jennings similarly expresses his gratitude for the invitation, which did not impose expectations on the Ojibwe musicians. Jennings was told that they could “collaborate with other artists if you want to, sing some songs in the woods, sing some songs on stage, sing whatever you wanna sing, with whoever you wanna sing with,” which allowed for a type of trust and authenticity that he was not used to.

“I told them I wished more people thought like this — that instead of reading from some land acknowledgement, that they would say, ‘We’re gonna give your people space and just invite you to do what you wanna do,'” Jennings adds in the press release.

“There’s a lot of people who we met just because of Eaux Claires, and a lot of relationships that we’ve maintained throughout the years,” Rainey says. “That was 2016, so here we are, 10 years later, creating music. I think those conversations were had initially at the festival, but we kind of let it happen; kind of let it grow on its own.”

Among all of the musicians’ busy work, life, and powwow schedules, Unbound was allowed to take the time that it needed to take to develop — and that process took more than three years. The album was formulated through a mixture of full-room jams, spontaneous improvisations, and carefully-composed tracks, which were then brought into an iterative process where each band member provided feedback before the tracks were further reworked. Major time was spent in the studio editing, arranging, and producing the album, and a number of guest musicians were invited to bring their instrumental expertise to select tracks.

“[Being] in collaboration with [multiple] genres of music, I think, sets [Bizhiki] apart from other material you may listen to,” Rainey explains. “Native voices with contemporary music has definitely been influential in my life… [As] a powwow singer, having a connection through music has always been with our own Indigenous people… so making our way through new avenues in music with contemporary artists and musicians: it’s different, but it’s been done before.”

An Invitation to “Come Through”

The project’s name, Bizhiki, comes from Bizhikiins Jennings’ given name, which means “Little Buffalo.” It was given to him by Eddie Benton-Banai, one of the founders of the American Indian Movement and Jennings’ wenh-enh, or teacher in Ojibwe. Honoring the Ojibwe language is prevalent throughout Unbound, whether through lyrics or song titles.

Unbound‘s lead single, “Gigawaabamin,” translates on the album to an English-friendly, “Come Through,” though the common Ojibwe word in fact translates more accurately to “I will see you.” The Ojibwe language does not have an equivalent to the English “goodbye”; thus, the translation “Come Through” invites an inclusivity and ongoing sense of community that Bizhiki endeavors to model through their project.

Produced and directed by Wisconsin-based Finn Ryan — who also did the band’s music video for the track “Unbound” — the music video for “Gigawaabamin (Come Through)” was one of the first pieces of media the group released. Filmed against a backdrop of trees, the imagery is proudly Ojibwe; it features traditional singing, ritual smudging, and hand drums, set around a game of baaga’adowewin — a type of Native American lacrosse that was played by a number of other tribes in the region. All that is also contrasted with skateboarding and bold graphical overlays.

The track and video are celebratory, playful, and welcoming, speaking to the values that the musicians have brought to Bizhiki. That ingrained sensibility can be attributed to a number of factors — not least of which is Jennings and Rainey’s history as powwow singers. As Rainey explains, “Powwow is in ceremony to Native or Indigenous people here… we all carry ourselves with respect and humility and with the things that we were taught.”

While many varying stories point to the origins of powwow, they have become important spaces for Native Americans to celebrate their cultures in ways that feel resonant for them. Powwows are an expansive constellation of events filled with artforms of all kinds, whether that be expressed through singing, drumming, dancing, regalia, beadwork, or food.

Some cultural crossover and consistencies can be found at powwows, but nuances exist. At the time of his call with REDEFINE, Rainey was at a powwow in South Dakota, where powwows are conducted differently from those in Northern Minnesota. As he explains, “To have that knowledge and awareness is something that we hold and we keep close to our hearts and our minds, because we always walk with our spirituality and our daily traditional things that we’re taught to do.”

Keeping powwow tradition in mind was central to the songwriting process for Bizhiki. Powwows have vocal songs and straight songs — those with and those without vocals, respectively — but for the untrained ear, the songs may sound similar. Still, for the initiated, protocol, rules, and traditions are important. In order to contemporize powwow music respectfully, well-versed musicians such as Jennings and Rainey understand what types of songs are acceptable for more contemporary or secular uses.

“When we’re creating things, we definitely want to walk that line of: we know what we’re singing isn’t stepping on any ceremonial toes,” says Rainey. “We are aware of what is in ceremony and what’s powwow — and what kind of things that we do at powwows that reflect our ceremonies, but aren’t strict teachings.”

Bizhiki hopes that listeners can keep these intentions in mind when listening to their music, while at the same time, not feeling overburdened by them.

“We invite people to, obviously, give respect, but also just to enjoy the music for what it is and not get too worrisome about if they’re appropriating…” Rainey comments. “This was all made within collaboration guidelines — even outside of those guidelines, just because of how new this might be to some people who are [not] privy to what we do year-round.”

Free-Flowing as Mother Nature is

Prior to the release of Bizhiki’s record, Rainey had just come off of releasing his 2022 solo record, Niineta, in collaboration with producer Andrew Broder. Niineta — which is much more experimental and electronic than Bizhiki but similarly provides a contemporary take on powwow-influenced music — was able to take Rainey all over the world. Touring his own record before Bizhiki’s prepared Rainey for the group’s eventual release, and some of that preparation is even a bit existential.

“Having [Niineta] come up before [Bizhiki] helped me utilize some tools that I have picked up along the way about the music biz, traveling, things like that,” Rainey explains. “It’s always walking a fine line between your tradition and contemporary ways. It’s a difficult life, especially for Natives, because we’ve got to get in our cars and drive places. We always try to take care of our Mother Earth, and it gets hard sometimes.”

Unbound is certainly not an “environmental” or “nature” record, but themes related to Mother Earth are ever-present throughout the project, whether that be taking care of one’s surroundings, experiencing environmental grief, or heeding messages which are born out of catastrophe. Rainey describes the title track, “Unbound,” as a “collection of thoughts,” but also a poem of sorts. Its lyrics came to Rainey in a time of great grief; writing the track assisted with his mental health and helped him release some of that grief.

“There [were] some natural disasters going on: wildfires, certain things that were obviously out of humans’ control,” he recalls. “We can’t control what happens… we have literally no control over… mudslides or hurricanes or tornadoes. Those things can take away people’s livelihoods.”

Despite such heaviness, Rainey was able to find potential opportunities to see the silver lining. Referring to Mother Nature, “Unbound”‘s lyrics calmly state:

Feel the heat

Taste the air

Seas what brings

Be calm when she speaks

Be calm when she speaks

She speaks the truth

“When something huge happens to impact your life, you really kind of internalize a lot, and some of it might be: this was the act of nature. This is Mother Earth somewhat speaking to us, and she might be speaking the truth,” Rainey comments. “If it means the truth [is] washing away your house in a flood, the truth is ‘Unbound.'”

A deep connection to nature is fundamental to who the members of Bizhiki are. Rainey describes Carey as an avid fly fisherman and Jennings as a lifelong preservation worker who holds a key role with [Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission] (GLIFWC) — a well-known organization which, among other things, helps to preserve natural resources for the Ojibwe, such as health and access to manoomin, or wild rice, a key traditional food that is foundational to Ojibwe prophecies.

“There’s nature elements in a lot of [the songs]. [In] some of the Ojibwe words that are said, [and] some of the naming of the songs are… feelings that we get from nature,” Rainey explains. He cites “Float Back By” and “Nashke!,” which translates loosely to, “Look, behold!,” as specific examples.

The incorporation of nature into Unbound was wholly natural, as the album was very much created in nature. The studio was located in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, where Carey lives — and it wasn’t uncommon for the trio and their collaborators to wander through the woods and then head back into the studio.

“I don’t want to call this a nature album… this isn’t like rain falling when you’re listening to it,” Rainey jokes. “[But] we definitely wanted to keep that [free-flowing] aspect of nature… We were just allowing things to happen naturally.”

The free-flowing nature was found throughout the album’s songwriting process and showed up in differing ways. Rainey recalls that vocals on tracks like “Franklin Warrior” and “Float Back By” were done as one-takes; the vocalists spontaneously came up with appropriate vocals as they heard the music. Some song titles and themes also emerged in free-flowing ways.

One such example was “Rez News,” which was written during the COVID-19 quarantine. During the songwriting process, Jennings and Rainey would sometimes sit in the studio’s live room, throw on their headphones, and listen to some of the musical components that the other musicians had made, such as a tempo or a melody, in order to decide what to sing. On the particular day of “Rez News,” it had been a while since Rainey had seen Jennings — who generally doesn’t participate in social media or have too much screentime — so Rainey was sharing some news about people who had passed away in the powwow community.

“The song was playing in the background… if they played the tape back, it’s literally five minutes of us talking about people who died…” Rainey recalls, with a sympathetic laugh. “We were talking over the microphone, so it was like we’re having a podcast about these people dying, because we had our headphones on.”

“Sean and Brian and those guys were so nice,” Rainey continues. “They didn’t stop the track; they just let it play.”

Thus was born the song title, “Rez News.” The song’s simple and somewhat cryptic lyrics may not immediately reflect the aforementioned content, but they are strong and reassuring at the same time, as if they are reassuring piece on the other side, or that everything will be alright:

Fortress now, where the rain never lands

Fortress now, you’ll never understand

Fortress now, the water is wide

Fortress now, on the other side

Centering patience, trust, collaboration, and relationships were key to the success of Unbound. Rainey stresses the importance of recognizing all of the collaborators that played a role in the album’s creation, which carries themes of significance to Native American communities, but also holds universal appeal.

“[Producer] Brian Joseph really laid down the groundwork and the environment for us to create a lot of the things that you hear,” says Rainey, in conclusion. “The support of our families and our communities [is also] going to help us go to different places and perform.”

“We always want to give thanks to our family and our loved ones, and also Mother Nature, Creator,” he continues. “We always want to give thanks to everyone that helped us along the way.”

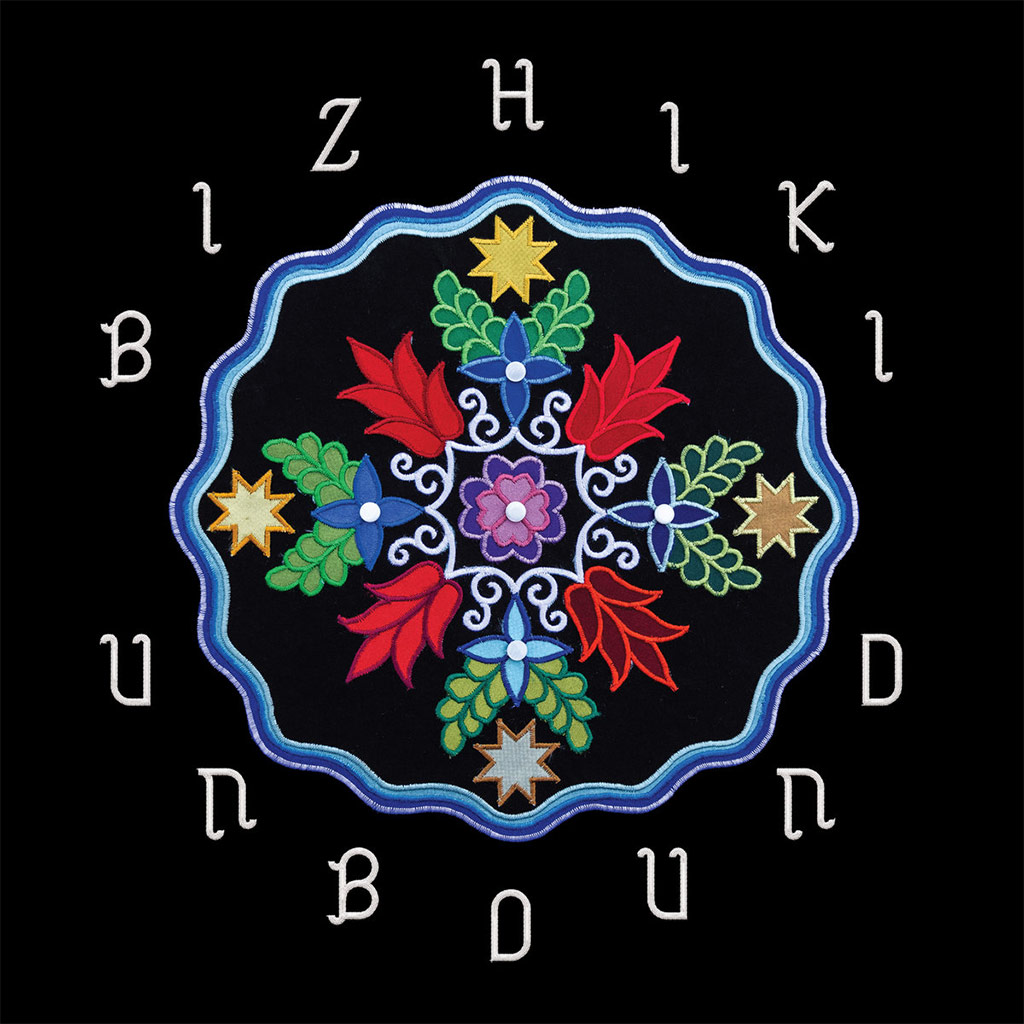

Unbound album artwork by Jennie Kappenman, featuring Ojibwe floral satin applique, and graphics by Art & Sons

Ω