The Role of Art Through an Immigrant’s Journey

Ghirmay’s original homelands were in Eritrea, but he lived in Sudan before taking a lengthy journey throughout Latin America and eventually to the United States. Those early memories helped shape his artistic style in conscious and unconscious ways.

“In Eritrea, I think there were a lot of [artistic] influences [in people’s] lifestyle… you don’t have to be an artist to live it,” explains Ghirmay. “The way that people live back home, there was a lot of art craft or [art in] the way people decorated their houses or their clothes.”

When he was twelve or thirteen, Ghirmay moved to Sudan, where he lived for four years. As he explains, “[Being in Sudan] widened my experience and interpretation of art, because Sudan also had a very unique culture — a very unique way of living their lifestyle. In hindsight, this was something that probably influenced me to be the person or the artist that I am now, but at that point it was, I was just living.”

Though Ghirmay did not speak fluent Arabic — the language spoken by most people in Sudan — Ghirmay believes that art and music transcended the need for language. A similar experience happened as he traveled through Latin America during his immigration to the United States. While he didn’t speak Spanish, art allowed for a different level of connection.

“I had to go through over 10 countries in South and Central America… that adds into your palette; [your personality] as a person,” Ghirmay explains. “Your artistic experience or your exposure gets wide. You see different people use different types of art.”

While Ghirmay has always been artistic, it was only when he reached the United States that he finally stepped foot into a gallery space. He also began taking painting more seriously, initially through art classes at his high school, where he received more clarity about his future direction.

“There is also a culture shock when you move here. There’s so many things that you’re expected to know, but I think that space in my art class was very therapeutic for me,” says Ghirmay. “I always would stay later after class and kind of try to spend as much time [as possible].”

Images from Journey to Serenity & Manifestations show at King Street Station (Photos: Marcus Donner for the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture)

An Amalgam of Scenes, People & Places

Because Ghirmay was exposed to so many cultures from a young age, he naturally spent many years asking himself existential questions about place and his sense of belonging.

“What’s home? What’s your identity? What’s your relationship with one culture versus the other one?” he questions. “Art has been something that was very consistent through different cultures that I’ve been through, and that’s something I would like to convey. I just want to make [my art] as boundless as possible.”

As an immigrant, Ghirmay has long felt pre-defined by labels that are sometimes imposed upon him. Thus, he endeavors to create artwork that can be free of such pains — using stories that might resonate with viewers, regardless of their identities.

“There are always a lot of categories that get put on you, like, ‘Oh, do you have this? Are you citizen yet? Are you a green card holder yet? Are you a refugee or not?'” says Ghrimay. “I feel like we are beyond that.. [yet] we are kind of worried [that it’s too] engrained that you can’t even think outside of that.”

Ghirmay often takes inspiration from an amalgam of inspirations to create a final product that is at once familiar and difficult to place. One of his recent series, The Journey Towards Serenity, was influenced by street photography. He looked at buildings on his travels, and they inspired him to think outside beyond a simple portrait, even though his works are often figurative in nature.

He began to think about the journeys that surrounded the subject matter of his paintings. From there, he crafted the stories of the paintings piece-by-piece, part-by-part, drawing inspiration from random fragments of life.

“Sometimes, when I start a series, I would see people walking around, and I would see interesting colors, and I’m like, ‘Okay, now I have this, and I’m just gonna incorporate this,'” comments Ghirmay. “For some of them, I would use my own clothes as an inspiration. I think one of those pieces has my jacket, so there are snippets of different moments.”

Approaching his work in such a way certainly makes sense for Ghirmay, but he finds that the explanations at times come off as too complex or difficult to understand for some viewers.

“I think people like more of a direct connection, like, ‘Is this your home country, or have you been to this place?’ and it’s like, ‘No, it’s a bunch of different things,'” he shares. “I don’t even know where it is, but it’s probably from places that I’ve seen… it’s a collection of different things, and I can’t even pinpoint one subject.”

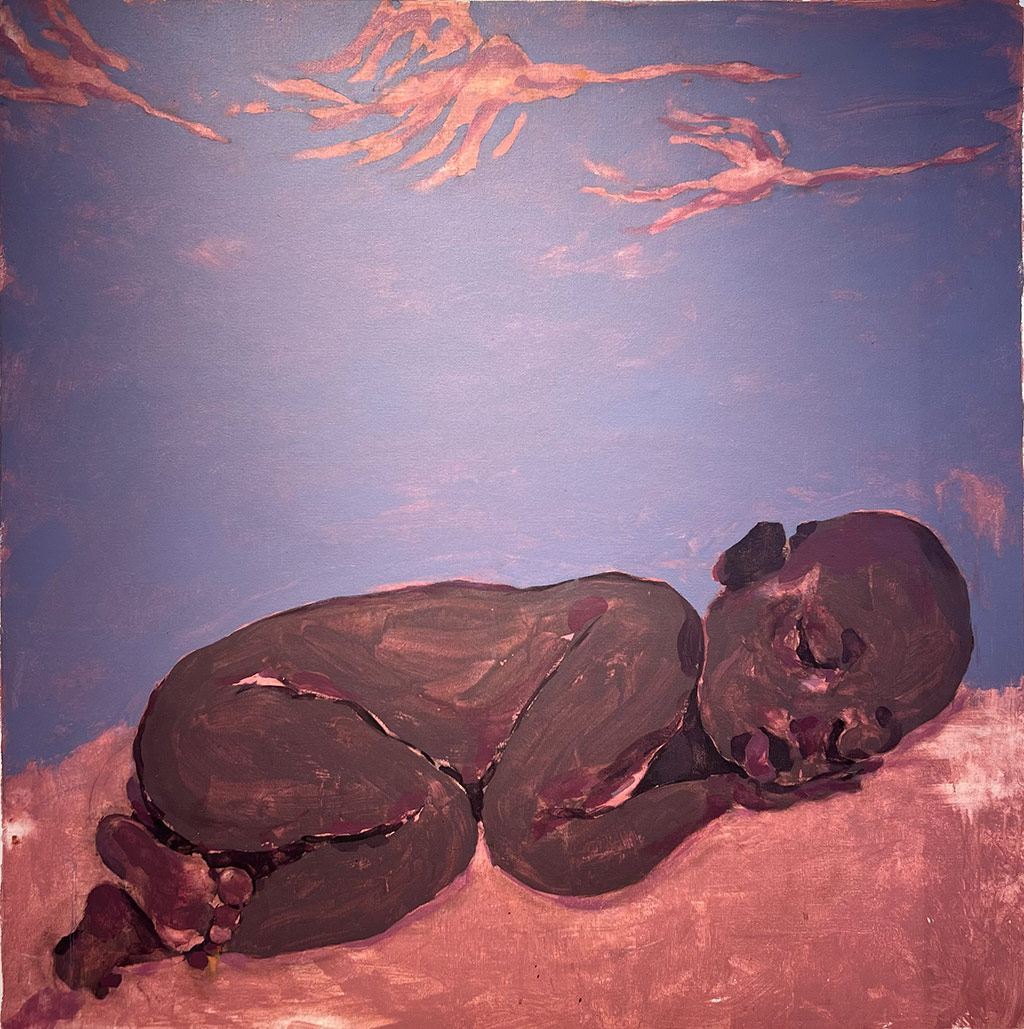

TOP: “Dreaming Paradise II”

MIDDLE: “Unrequited Love”, 24″ x 24″, acrylic and oil on canvas

BOTTOM: “Solitary Contemplition”

Finding Inspiration from Within

After Ghirmay graduated from the University of Washington in 2019, he was afforded the time and energy to seek answers about his personal motivations and life purposes. He discovered that introspection, his inner states, and his imagination were the places where he could find “a sense of heaven” — a place that he could control, even despite problems that might exist in the world.

“During my reflections, I thought about my coping mechanisms…” Ghirmay recalls. “When I was in a darker place, I think one of my tools was imagination or just dreaming of a place, and kind of imagining myself as I am in that place.”

The need for coping mechanisms comes as a reaction to many different things. Ghirmay notes that immigrants often don’t have the luxury to sit and reflect, and mental health can be stigmatized in certain immigrant communities. It requires a certain mind — and the gift of time — to find methods to keep themselves mentally healthy.

“Something that I’ve realized was that [when] I think [about] the concept of finding home, or trying to relate to people… there are a lot of external factors that you can’t control…” says Ghirmay. “It’s just too much tied to the system — tied to different institutions that makes you less human or tries to put you in a certain way.”

With his Inner Child series — which is highly tied to ideas of inner peace — Ghirmay recreates some of the imaginary scenes which have helped him through dark times. It’s a tool that he continues to use to this day, and he hopes that by painting them, he will also help others feel a sense of comfort.

“I just zone out… I kind of try to take my mind into the place…” says Ghirmay, regarding the process of accessing his imaginary places. “When I get into that state, I just imagine myself as an inner child… My concept was, ‘Okay, this is you now, but there were some points where you didn’t know anything; you were uninfluenced or unexposed.’… it was kind of like an escape mechanism, in a sense, but it works.”

MIDDLE: “Crimson on Blue”, 20″ x 16″, oil on canvas

BOTTOM: “Flavors of Diversity & Colors of Community”, sculpture

The Irreplaceable Power of Color

Not all of Ghirmay’s pieces are so abstract in their origin story. His first sculpture piece, 2024’s “Flavors of Diversity & Colors of Community,” is one such example. Influences by palpable memories of visiting spice markets in Sudan and Eritrea, the playful sculpture is installed at Jefferson Park within Seattle’s Beacon Hill neighborhood and uses pastel-colored rocks to convey the idea of diversity.

“Everyone kind of comes in different sizes, in different colors to make this life vibrant and interesting…” explains Ghirmay, of the original constraints he placed upon himself. “I think the spice market was one of the most colorful, vibrant settings or scenes that I’ve seen in a lot of places I’ve been to… and I think those spaces brought everyone — people from different social classes.”

With that concept in mind, Ghirmay explored how he might be able to make a sculpture that wouldn’t require complex fabrication. He settled on rocks that he painted in different colors to symbolize the spices — and naturally, their different shapes and sizes represented different kinds of human beings.

“Having multiple colors in one sack was very intentional, because I think usually, it would be one spice in one bag,” says Ghirmay. “I kind of mixed it in, and was like, ‘Okay… I think that would communicate the idea of diversity [and] community in the most simple form.'”

Ghirmay also experimented with new materials. Not long before his creation of the sculpture, he had broken his arm for the first time and opted for a waterproof plaster cast. When it came time to decide how to make the sack that held all of the spice market rocks, Ghirmay opted once again not to go the route of fabrication, but purchased large amounts of fiber cast.

“I picked the color blue to symbolize the ocean, because I feel like water and the ocean can [offer] a very calming, relaxing effect,” explains Ghirmay. “Also, [I like] the idea of the ocean holding a bunch of creatures together.”

The result is a piece that seems delightfully soft, though it is actually sturdy enough to outlast the harsh elements of the Pacific Northwest. Ghirmay’s choice of colors also connects the sculpture back to his painting practice, though the connections would otherwise not be as obvious. Color theory is something that Ghirmay takes very seriously. He challenges himself by generally working with an extremely limited color palette — one that usually begins with just the primary colors and the addition of one more color.

“I feel very strongly about colors. I think I have a sensitivity toward how colors evoke emotions or certain feelings…” he says. “I think that’s one of my favorite parts of painting: finding the right tone for the right painting.”

Ghirmay admits that if one were to visit his studio, one might see ten to twenty shades of a single color displayed next to another, just so he can better understand how the colors interact with one another. It’s a process he thoroughly enjoys and takes his time with.

“Once I figure out the color, [the painting is] the easy part for me,” Ghirmay states.

“Maybe adding the lines [or] giving more features would help form your ideas, but sometimes, I think you’re also taking the… freedom of interpretation from people,” he continues. “Color is a very simple way to communicate feelings and emotions.”

Perhaps it is Ghirmay’s wide understanding of the world — or his approach to art, which pulls from numerous, often unplaceable influences and mashes them into a cohesive painting that is full of imagination — but it makes sense that Ghirmay prefers to allow his art to speak for itself.

TOP: “Dreaming Paradise”

BOTTOM: Portrait of Nahom Ghirmay with “Dreaming Paradise”

Ω