Tell me how you came to understand the significance of birch bark — both for you personally, and then how it evolved to be important to you as an artist.

Phillip Gladkov:

This necklace that I got [around] 2015 was what brought birch into my awareness. Obviously, I’ve been around it a lot before then as a kid. There [were] things in my house growing up made of birch that I just didn’t know what they were. My dad came back from Russia, and brought me this medallion. I don’t know what it symbolizes, to be honest, and neither does he, but he brought it back, and I’ve worn it almost every day ever since…

At the time, I was working on a documentary film in upstate New York, and there just happened to be a lot of birch trees [there] also. It was almost kind of coincidental that I got this necklace and was in that place. [I then] just started paying attention to them a lot more and appreciating all the different colors and textures that they have. I’ve always been someone who has a deep and profound love for the forest and nature in general. And this was just an extension of that.

So I started kind of collecting pieces of dead birch from the ground, not really knowing what I would do with it, but just loving touching it and looking at it. And as it was there on the ground, I wasn’t feeling too bad about [it]… I [wasn’t] ripping them off the trees and stuff.

One day, at home, I was looking at the pieces, and — naturally being an artist, I was like, “I should make something out of this,” and I made my first piece which was a little mountain. It was Mount Algonquin in the Adirondacks in upstate New York. And I liked it, and other people liked it, and I was just kind of, “Hmm, this is interesting — making collages out of this beautiful bark that is almost paper-like in texture.”

They just started there. I made one after another, and now I think I have maybe… around a dozen of these giant collages of birch bark that are very special to me.

Portait photos by Johnny Frost

What have you learned about the way that birch bark grows or flakes — or how the colors turn? Because I’ve been astounded by the incorporation of color in your work.

Phillip Gladkov:

Betulin is the compound that gives birch trees their distinct white appearance.

And the reason they’re evolved to be white: one of the theories is that dark trees in the winter can absorb a lot of sunlight on one side, and with nightfalls and temperature differences, that can lead to condensation, freezing inside, and a lot of problems. So, it was beneficial for the birch trees to be white, because they would reflect the sunlight in the winter and would kind of stay uniformly the same temperature.

And they were one of the first trees that came when the ice started melting from the last ice age, I believe, because they’re a pioneer species. So they’re in these cold environments, and it was just beneficial for them to have white bark.

So it grows in Russia and in New York?

Phillip Gladkov:

There’s a lot of species of birch. This necklace that I’m wearing from birch is probably a different species then one that I was collecting in New York, though they have similar properties. The species that I collect in New York and Vermont and New England — and that’s pretty popular, I guess, in North America — is betula papyrifera.

Birch grows all over the world, where the habitat is right for it. Mostly colder, higher-altitude places. And wherever it grows, people have used it from the beginning of time… one of its simplest functions as bark is as a fire starter — it’s very flammable — to then, utilitarian things, like baskets, and here in North America, canoes and shelters for homes. Once it gets beyond that, it’s craft purposes, like making beautiful things [such as] earrings, ornamental [objects]…

The uses for it are endless, and that’s like, one of the things I love — that all around the world, people have come to love and revere this tree, because of its benefit to us and its beauty.

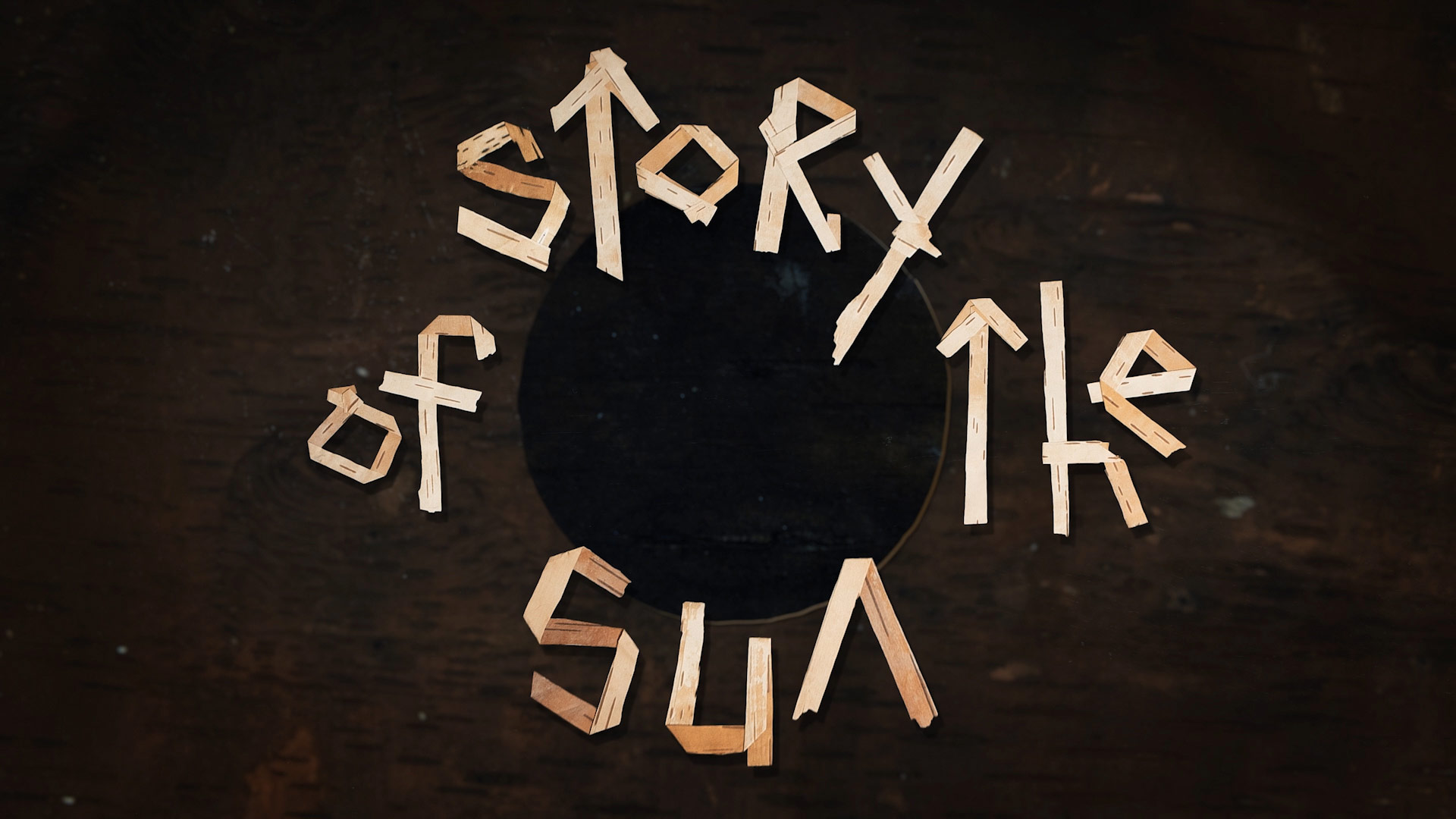

How did you come to develop the concept of Story of the Sun

Phillip Gladkov:

I was telling a bedtime story to someone. They asked me to make one up on the spot, and I told the story about the world before the sun and where the sun came from, and I kind of just said it in one go.

I have a book about myths my friend gave me while I was working on this project — about sun myths and origin stories from all around the world. One of the most interesting things I found in it was that while there are many different creation myths about where the sun came from, one really common thing is that people describe this world of darkness before the sun. That’s a common factor.

That’s something I think about a lot — the human curiosity of thinking of… “What was it like before the sun? “Even though now science has other explanations, we all have our own explanations too.

That’s where the written portion of [the story] came from. I wrote it down in a phone note the next day or something.

I feel like there’s like a bit of a morality tale in there. Do you see it that way?

Phillip Gladkov:

I always want to make art — at least in films and my storytelling arts — that’s like a little bit of like, a love letter to humanity…

Sometimes, I think about how young we are as a species, and how we’re still kind of in a childlike state. Even though we have this highly advanced technology, we still kind of operate in a very — I don’t know the right word for it, but childlike way… not always forward-thinking.

There is morality in it… you can look at these primitive birch beings and be like, “Oh, man, they’re so stupid! They let fire destroy their whole village,” and then you think about humans and climate change where we’ve come to like the point of making the planet uninhabitable in several decades. It’s not too far off of a metaphor.

Right. And also, fire being this interesting thing, because we control it so much that the lack of regular controlled burns has become a problem for wildfires.

Phillip Gladkov:

Yeah. Wow. It’s also really cool that the film is made out of birch bark, because it was a material that was probably — by the earliest humans and even maybe even pre-humans — discovered to be very flammable and used very much so.

They found a lot of birch tar in Neanderthal firepits. They either think they use the tar because you can use it as glue [and] they either figured that out — or other people are arguing now that they were just burning birch, and that’s why there’s tar there. So, it’s debatable whether they knew its many uses, but that’s still cool.

I actually didn’t know birch had tar.

Phillip Gladkov:

It’s quite sticky. I’ve actually made it before myself out of the scraps that I use for my birch pieces. You basically have to burn it without it getting burnt — without the fire actually touching it. You have a hole in the bottom of a tin can, and you can collect this tar that’s kind of what remains.

It’s black, and it smells like smoke, and you can use it as a slightly-functional mosquito repellent if you have nothing else. And if you keep boiling it, you’ll make it into more of a sticky glue that is very sticky, and you can bind wood with rocks to make hammers… and stuff like that. That’s another thing that birch was used by people all around the world for a long time.

That’s fucking cool. How long did this project take you? And you mentioned stop-motion — but what other if any animation techniques, if any, did you employ in the process?

Phillip Gladkov:

I first told that story [in] 2017, and I’ve been telling the story since, but I always thought: it would be nice to make an animation of this one day. And, finally, that one day came around [at the end of] 2021, I was like, “I gotta start working on this.”

It wasn’t until… the beginning of 2022 that I made a storyboard on a giant piece of paper. And then, it wasn’t until I moved to LA that I actually started working on the animatics… and further storyboarding and developing it.

Principle animation probably began in October 2022, maybe… It really kind of blurred. Time blurs, because you start working on a project, life gets in the way, you put it down, and then you return to it.

Are you the type of creator who gets really in the hole with animation stuff?

Phillip Gladkov:

Yeah, yeah, but this takes so long that you can get in the hole, and then it’s time to get out of the hole, and then you have to get yourself hyped to get in the zone again, because you can be at it for like two weeks, working full-time days, and only be 5% done. Or, like, even less, honestly. So it’s definitely a marathon.

When I first showed [my friend] the animatic and was getting his feedback, he was like, “Just get ready, because it’s gonna take a lot longer than you think,” and I got kind of mad at him for saying that. I’m was like, “No, I’ll have it done in no time. What are you talking about?” and he was totally right.

In addition to stop-motion, what were some other animation techniques you used? It looks like there’s some CG or VFX stuff.

Phillip Gladkov:

A lot of the characters were stop-motion. Some of that would be in-camera stop-motion that I would do with them, and some of it was: I needed to get a shot, and I didn’t necessarily have the time or resources to recreate it in stop-motion again — and so, I would just rig puppets in AfterEffects and put the birch texture onto them.

It’s a good mix of stop-motion and AfterEffects comping.

Because the birch bark is really precious to me too, I can’t just be like cutting up infinite amounts of pieces of it, because I use it for my fine art.

It’s just such a sacred and valuable material to me that I tried to minimize waste as much as possible… I don’t live somewhere where I’m around birches right now, so all of my pieces are very important to me, and it pains me so much to cut into them even when I’m working on a piece I really love.

[Regarding the fire,] obviously, I added a lot of like glow effects to it and things like that, just because birch bark has its limitations, and there’s some effects I’m just not gonna get out of it.For me, the story is always the most important… Do I think it’s sacrilegious to not have 100% of it be pure, traditional stop-motion animation? No, because I don’t think that’s practical. It’s also a privilege to have that much time to devote to that. I don’t necessarily have that much time to do it a certain way, just for the ideology of only doing it in that way. I don’t; that doesn’t matter to me.

Phillip Gladkov’s fine art birch bark pieces.

What was the process of working with your composer and your narrator? What guidance did you give them, or what was the collaboration?

Phillip Gladkov:

I was really lucky to just happen to work with two really awesome people that it was a pleasure to collaborate with. The voiceover person — I’ll start with them: Tsukuru Fors. I was searching for a voice that sounded ancient. Not old, because that’s… two kind of distinct things. A person can have an older-sounding voice, but [not] have that kind of mysterious timbre and quality that an ancient-sounding voice might have…

For telling a story like this, I wanted a certain quality of voice. I knew what I wanted, but I couldn’t necessarily describe it, and I knew very easily what I didn’t want it to sound like. It was really hard to cast someone. I got a lot of talented submissions — honestly, probably over 100 — but when I heard Tsukuru’s voice, I was like, “They are the one.” And I reached out, and they’re really cool. They’re an activist, among other things, and a voice over artist, and I kind of just got along with them very easily off the bat.

At first, they sent in some recordings that they did on their own. And we would workshop them, and I would give notes. And finally, we had a recording session in person, and my partner — who helped me a lot on this film — was present for that too. She gave notes as well, and it was really helpful to be there in-person and… hear a take and then be able to give some feedback to Tsukuru that, “Hey… this is the emotion of this part,” [or,] “This is why this part is important,” and they would be like, “Oh, okay, knowing that. I can deliver this line a little bit differently.”

By the end of that session… I was like, “This is it; this is the voiceover.” I couldn’t have done the film without them, because their voice is… the guide that guides us through the story of these little birch people…

Honestly, all the way up until recording the voiceover, I was like, “Do we need this? Can I tell this story visually, without voiceover?” Because it’s so much more inclusive when you don’t have a voice in one language — but there are certain things that we’re just kind of lost in without it.

One immediate takeaway I had was, “Oh, their voice feels very timeless.” Even though obviously they’re speaking English, it’s not quite clear what their accent is.

Phillip Gladkov:

That was one of the things I was looking for… I grew up with parents who had accents; everyone in my family who had spoken English had an accent. And that’s honestly a quality I love… I grew up around different people who spoke different languages.

So I wanted that, but I also didn’t want it to be that distinct of an accent that you would be like, “Oh, this is like a Russian accent, or this kind of accent is from this place,” because this story isn’t really tied to any place. And I didn’t want there to be some kind of association like, “Oh, is this a South American story?” Because it’s not. I didn’t want there to be confusion around that, so I wanted an accent that wasn’t specifically tied to any place.

I absolutely love working with Tsukuru, and hopefully they’ll help me translate this into Japanese and we’re gonna do a Japanese VO voice version of it.

How about working with your composer?

Phillip Gladkov:

Lionel Cohen was really cool to work with. I put out a call for composers on Facebook and Craigslist… I had, I think, over 100 submissions too, and it was a lot.

I submit to a lot of things; I’m a freelancer. I’m constantly throwing my name in the ring, and so, I have the respect to listen to everyone’s things and respond to everyone… understandably, a lot of people submit to things, especially right now in this… very dry work climate, but I get upset when there’s not even a thank you… or, “Hey, we went with someone else.” So it took a long time to sift through everyone…

I had a few composers [whose work I really liked], and I talked to all of them. Lionel and I just felt like the best fit, and he was very accommodating and patient with all of my notes and kind of let me know, “Hey, you can give more notes. it’s okay.”

He’s worked on a lot of cool stuff, and he’s a bit more into his career, so it was good to work with someone who has so much experience. There were a few rounds of revision. I remember he did a demo where I was like, “Okay, this might not be like, 100% the final vision, but he gets it, and he knows the emotional tone of this piece.” And that’s the most important thing.

Without him this movie wouldn’t be what it is, because so much of the score is the emotional part, because otherwise, it’s just a birch puppets movie, you know? It really makes you feel how they’re feeling, and you know: the tragedy and the humor and all of that.

Ω