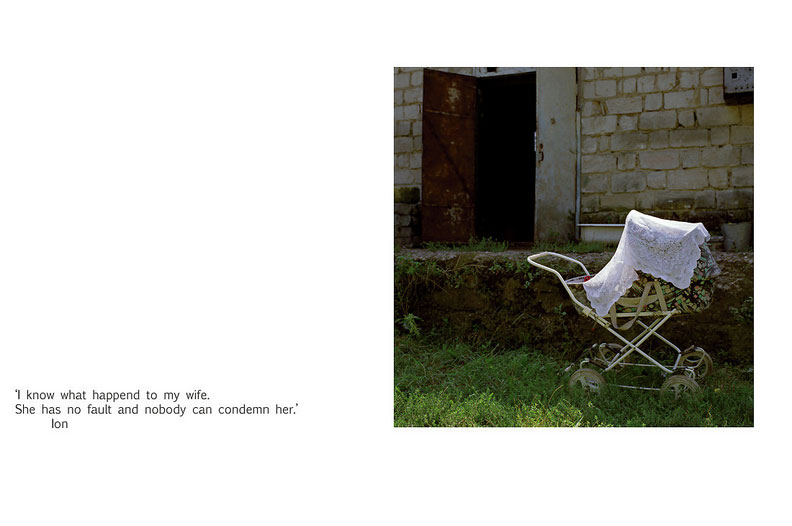

Many series about sensitive topics shock one into sympathy. Not so with not Natasha; its images are often profound in the most mundane of ways, focusing not only on the women themselves but on the things that they leave behind — while, in Popa’s own words, capturing “a glimpse of their souls”. It is beyond the photos themselves where the heart-breaking tales often lie, in the form of deception and betrayal from former lovers, neighbors, and friends, and of societies that allow women to be sacrificed to patterns of abuse and pain.

In the full Q&A interview to follow, Popa recounts incredible stories — some of which are difficult to believe — while motivating us with powerful imagery. For more details on how you can be involved in V-Day events, please visit their website, or see more of Popa’s work on her website.

(17 IMAGES TOTAL)

What circumstances led you to the not Natasha project?

What triggered my work was purely finding out what sex trafficking really means.

At the time, there was not much visual coverage of the illegal trade. Sex trafficking is the most profitable illegal business since the 1989 fall of the Soviet Union; it’s a form of violence against women from my society. Little do people realise what this illegal trade is and how big and profitable it has become. So I decided to try and get a closer look at sex trafficking and record what it means for the women to survive sexual slavery. I chose to have a glimpse of their souls — which at the time seemed very difficult to do, but that is what I was most interested in. After having heard their stories, I wanted to look at their traces — at what women who had disappeared for years and who are believed to be trafficked and sexually enslaved leave behind. This became essential angle and part of the narrative.

After being involved with this project I realised that its beginnings might have been triggered by my interest and knowledge of the woman’s position in societies like the one I was born in. I acknowledge this story as a way of standing up against the societies that know what happens to their women and hide it without even doing anything about it.

It must have been difficult to deal with such a delicate situation. Did you have training in communicating with these woman or face any difficulty? What were some solutions that you employed, and do you have any advice for those who are hoping to speak with a woman who has undergone sexual trauma?

The most pleasant part of the learning process was when I spent time at one of the shelters that offered them psychological assistance and accommodation for a month or so. I had spent two weeks with girls that just escaped sexual slavery. They were spinning stories about their ordeals every evening. This is what actually helped me frame the story and urged me to continue it at a later stage. The women accepted me in their lives, some for three weeks, some only for a few hours, depending where I’d meet them. They all understood immediately that I was not going to harm them in any way. It was not hard to explain the reasons of my work.

I did not have an official training in communicating with the women I photographed and interviewed. I acted instinctively, seeing their dignity, their strength and delicacy at the same time, their sense of respect for other human beings even after surviving such ordeals. Also, that hidden hope that lived in each one of them. I used to share long walks in the park with the girls at the shelter. They love the Saturday morning walks when they can watch the brides of the day. They just secretly hoped one day they can return to normal life. I was both discreet and protective, respectful to their wishes, and always asking for their consent.

One of the best pieces of advice that I had received in regards to portraying survivors and which I would say in my turn was to approach them with respect, to firstly see and show their humanity and dignity through my photography. Also, to have patience, something that I needed a lot in this long-term and slow-making project.

Are there any experiences from the women that you would like to share?

The women in these photographs are among seventeen I met, interviewed and photographed them. Some of them were too fragile; some very strong, trying to leave behind a hated past while still coming to term with profound emotional distress. At the beginning, they shocked me with horrific details about the rape and violence they had survived. They talked about the Odessa boat which later on I went on, too, about the brothels or rooms they were locked in, some for weeks, other for months or even for a year, about the way they escaped.

Aurelia, a girl from Ukraine, shouted at me, “My story, do you want to hear my story? You have heard it — over and over again.” Clearly distraught, she told me how, a year after she came back from the Czech Republic, the police came to the door and started to question her. Then her husband and her mother-in-law chased her away from home. They had not known she was sold as a sex slave by a good friend. Her life was destroyed, she said.

Dalia, 20-years-old, always dragging along her two-year-old daughter, was the first one I encountered at the shelter. Dalia was sold by her husband-to-be. This was a trafficker that acted on his own in Moldova and was dating girls from different parts of the country; after a considerate amount of time, he would invite them to meet his family in Turkey and get married. Clarisa was sold by her best friend and Elena by the old lady living across the road in her village. Svetlana by a woman at the market that she thought she knew very well and some others by relatives. In many cases, the girls and women sold as cattle on the black market are approached by somebody that they know and trust. Larisa had been trafficked into Albania; on her way to Italy, she fell in love with her pimp who fathered her twins. She escaped after three years.

In London, I met Svetlana, a young Moldovan who was sex trafficked into the UK. She showed me windows of particular Soho flats: the one with a cracked window was a “stinky” place; the one with a red light was a bit trendier. I later on entered five cribs with working girls. I met two Romanians on this occasion. One was wearing tiny white socks and a pink robe thrown over a black spandex costume. She was from a city two hours from my native town.

These women did not opt to become sex workers; they were locked in all sorts of locations, from flats and houses to brothels, threatened, beaten up and raped, put on drugs and alcohol and forced into it. When I researched my subject, it was shown that women from Moldova had been sent to as many as 42 destinations.

I am still in touch with a few of the women I met in this journey and in more often contact with a couple of them. As a reaction, they were interested to see my work. One of them decided to help me continue my visual work on sex trafficking as much as she could and another one looked on the book dummy with curiosity, since she had been very much part of the project both as a survivor and a great help in translating and making the liaison with other girls at the shelter. When she reached the end of the book, she closed it and said, “Okay, from now on, we won’t be talking about this anymore.” We still keep in touch.

How much responsibility do you feel as an artist to contribute to the world in a positive way or to bring attention to misdeeds in the world? Do you ever create without a narrative or mission in mind?

The same responsibility one feels as a person searching for virtue, which it’s probably a very innate human characteristic. But it doesn’t mean I ask myself that question when I look at one of my pictures — does it contribute to the world? It’d be a scary question and I wouldn’t know how to answer it. To answer the other question, I usually have a pretty good idea of what I want to do before start shooting — I wouldn’t call it a mission or narrative — which obviously can mutate throughout the process.

Ω