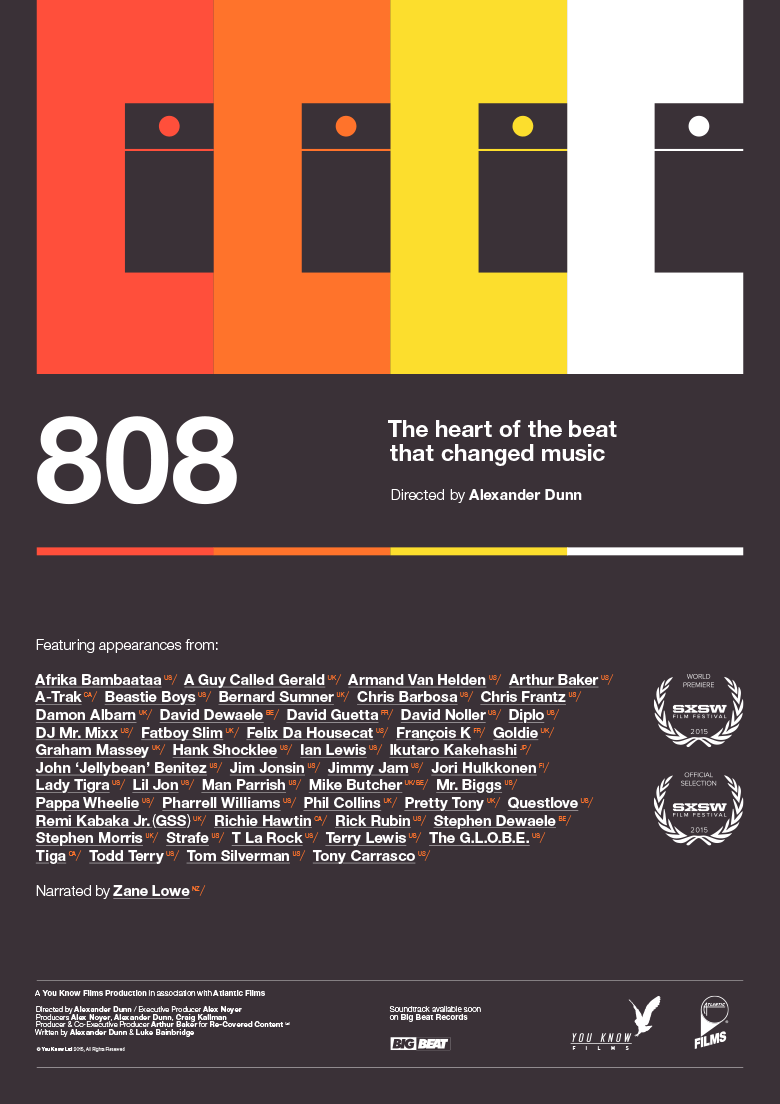

808 gathers an impressive list of producers, MC’s and DJ’s to illustrate what the 808 meant to them and how they harnessed its deceivingly quaint technology to bring electronic music to the masses. Figures such as Rick Rubin, Afrika Bambaataa, Arthur Baker, T La Rock, Strafe, Felix Da Housecat, and the Beastie Boys reveal dozens of interesting, meaningful stories telling bit by bit the origins of the drum machine in popular music. Some of these figures such as Lil Jon, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, aren’t given enough screen time to explain just how the 808 has influenced their works. And some figures, such as Damon Albarn, David Guetta, A-Trak, and many more, are given entirely too much screen time (in Guetta’s case, any time at all is too much time) and have nothing of interest to say whatsoever. Thus, the film suffers from long streaks of irrelevant and uninteresting banter, especially after a strong first act.

While the endeavor to touch every genre influenced by the 808’s sound is admirable, in no way is it fruitful. The first part of the film, focusing on hip-hop, Afrofuturism, and the exploration of drum machines by pop and soul legends, gives a wonderful introduction to the weight of the 808 in pop culture. But then the film regresses, dabbling in the origins of house and techno while leaping awkwardly into its many subgenres — spending a good 20 minutes on Acid House is baffling no matter what way you spin it. Not until we return to hip-hop and modern dance music does the film actually pick up in urgency, but by that time, 808 has already worn out its welcome. 808 feels in dire need of a historical editor; giving Tiga the same amount of focus as Afrika Bambaataa doesn’t make any academic sense at all.

The big reveal at the end features a direct interview with Ikutaro “Mr. K” Kakehashi, one of the very old but still-alive founders of Roland, and developer of the TR-808. Finally, the film talks about where the machine comes from and what makes the 808 so unique (and impossible to reissue). However, this section is presented with a jarringly Orientalist score — one that looms over the entire interview at such a high volume that it figures to be almost purposefully offensive. Surely someone must have watched the film to the end and said, “Maybe it’s not such a good idea to put 808 drums over stock bamboo flute melodies and crank the volume, drowning out the voice of the founder of the company that developed the main subject of your documentary,” but here we are.

And really, this is all in line with the film’s efforts. While purporting to extol the legacy of the 808, the film instead relegates it to a tertiary character, second to the egos and the personalities of one too many screen-hogging artists, most of whom have a negligible influence on the parallel development of the 808 and electronic music. The early adopters found the 808 appealing for the same reasons early critics hated it: because it did not sound like real drums, the machine had its own voice. This 808 documentary drowns that voice out entirely.

Ω