With the twangy plucks of a fiddle and the histrionic moaning of the word, “Daddy,” is our opening shot: in the background, out of focus, a man and woman have sex on a couch. In the foreground, a vibrating cell phone shows that Mom is calling. Shortly after the man comes, the young woman, Danielle, dismounts and steps into focus as she approaches her phone. Immediately after establishing Danielle as a sexual being, her mother’s voicemail rears her back into a place of childishness.

“Hi, it’s me, Mommy. Are you coming to the funeral today? We gotta leave soon,” says the voice on the phone.

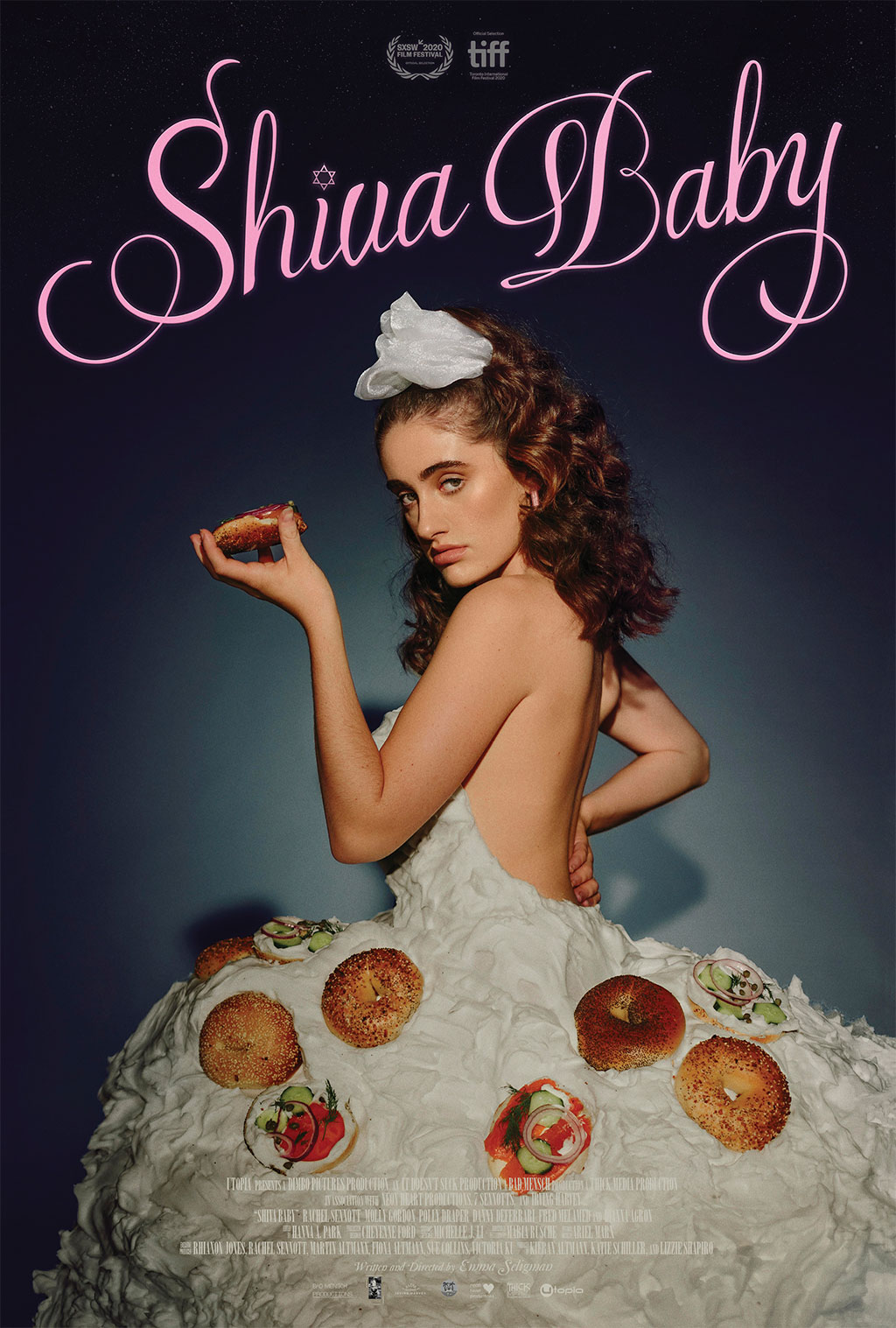

After an exchange of money and a bracelet, the man is revealed to be a client of Danielle’s. Danielle is a sugar baby — a young woman who exchanges company and sex to older men for financial gifts — but this is just part of where the film’s title comes from.

In an interview with Alma, writer and director Emma Seligman talks about “sugaring” which is common among New York University students, where she studied film. Having tried it herself, Seligman imagined how a scenario would play out where a sugar baby runs into her sugar daddy at a shiva, a Jewish ceremony for mourning following funerals. Moving into an era that gives voice to sex workers feels empowering, but as we see throughout the movie, Danielle’s decisions lead her to feeling trapped and confused due to her own immaturity. As Danielle inches toward her self-made degree in Business and Feminism, we see why she might be drawn to something like sugaring. She can be her own boss, create relationships on her own terms, and most of all, make money from doing so. But when she finds herself under the same roof as her parents, her sugar daddy, and even her ex-girlfriend, Danielle is reminded that in creating certain identities for oneself, you’re still under risk of scrutiny.

Seligman takes a moment of sorrow, at a shiva, and turns it into a script about relationships within a tight-knit Jewish community. Danielle’s reliance on her parent’s payroll keeps her under the thumbs of both mommy and daddy as well as her sugar daddy, Max. Her fabrication that she is a babysitter only gives way to more humorous wordplay and problems throughout the movie.

There is a stereotype about Ashkenazim — part of the Jewish diaspora who settled in the Holy Roman Empire, what is now Eastern Europe — as being neurotic and nagging. Seligman uses this as a tool in her script as both world and character-building. Danielle is constantly meleed by the other guests of the shiva. Does she have a boyfriend? How much does she weigh? What does she plan to do with her degree in Business and Gender Studies? Seligman’s dialogue paired with close-ups of Danielle perfectly exhibits the claustrophobic pecking endured at a shiva.

With more room in the feature film Seligman also chooses to include Maya, Danielle’s ex-girlfriend and childhood friend. Maya is on a path to become a lawyer and is, in general, just a Nice Jewish Girl; conversely, Danielle struggles to hold a conversation or eye contact with her elders. Danielle is not the most likable protagonist there is, but her struggle is certainly relatable. She is sneering and avoidant, even when speaking to Maya. The word, nebbishe—pitifully timid, comes to mind when it comes to Danielle. Her inability to be in control of the situation is what makes her struggle for independence so much more painful to watch.

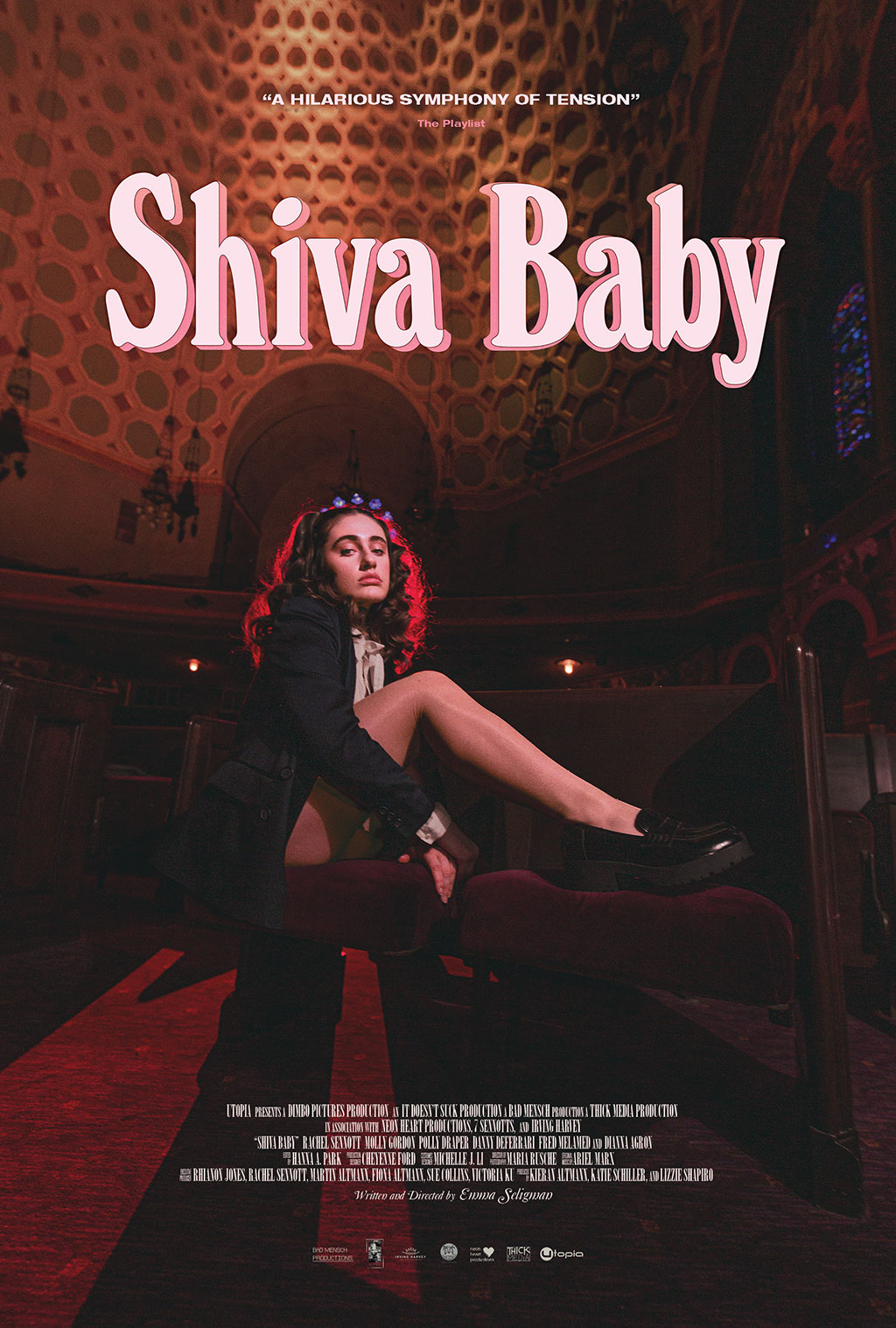

Shiva Baby Film Trailer

Ω