Misunderstandings of Grief

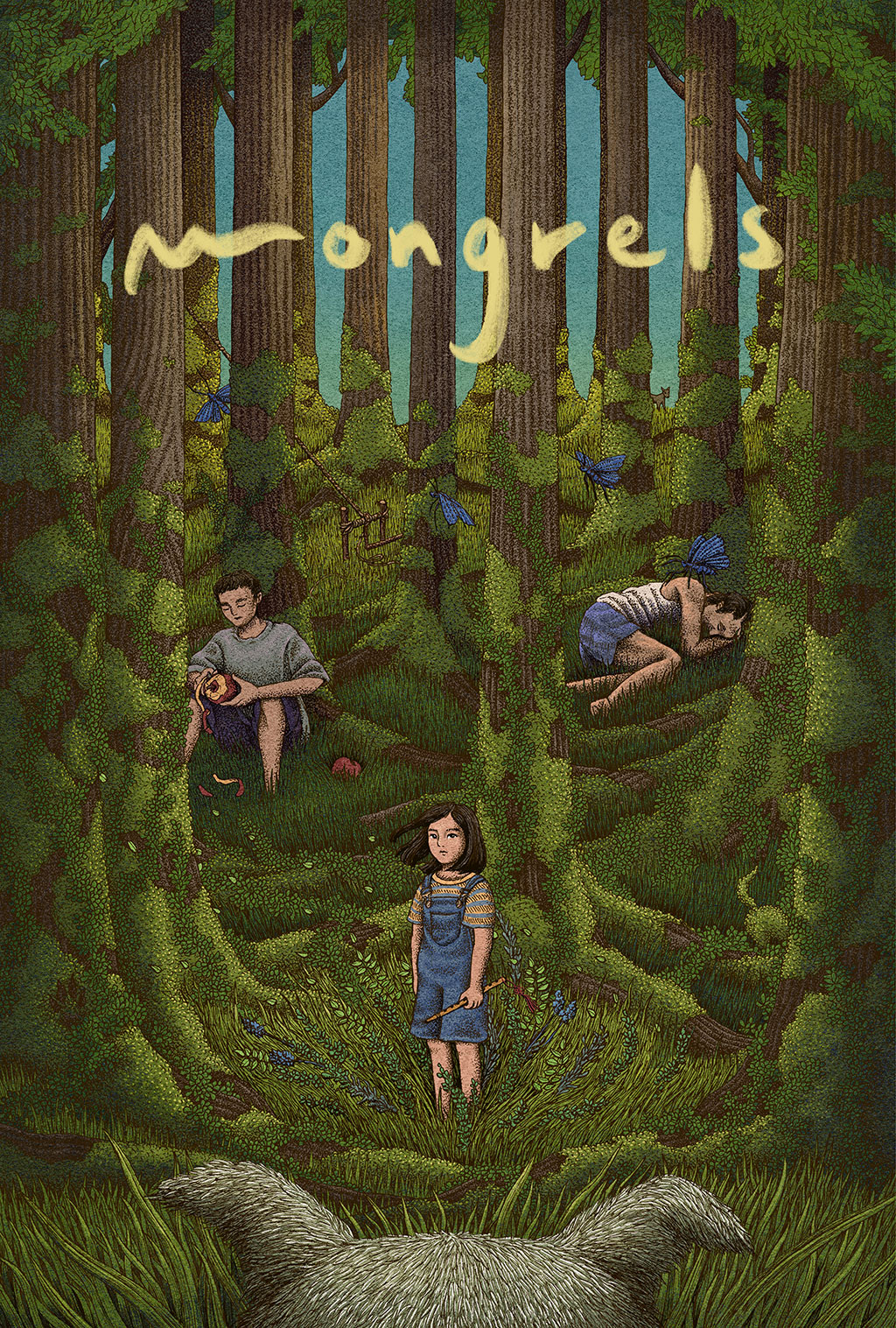

In the wake of the loss of his wife, Sonny Lee (Jae-Hyun Kim) uproots his family from their home in Korea to the Canadian prairies in search of a fresh start. Hired to help cull the local feral dog population, Sonny takes up arms against the mongrels that plague the surrounding forests – alongside the behemoth of his grief. As he attempts to build a new life without his wife, his son, Hajoon (Da-Nu Nam), and his daughter, Hana (Sein Jin), try to do the same, struggling to adjust to a reality that does not include their mother.

“Lost dogs seeking for a place of belonging, barking to take up space and to let their existence be known: this felt akin to the central family,” Yoo explains.

A key theme throughout Mongrels is the parallel drawn between the Lee family and the wild dogs that Sonny is expected to hunt and execute. The dogs, wandering in the forest, are greatly misunderstood, just as the Lee family misunderstands one another and are unable to recognize the common thread that runs through their individual pain.

Sonny, who masks the pain of his loss beneath a whirlwind of drunken outbursts and isolation from his children, is misinterpreted as a cold and unfeeling father in the eyes of Hajoon and Hana.

“Deep down, [Sonny] holds a powerful love for his children, but he doesn’t know how to express it or connect in the right ways,” Yoo says. “Vulnerability is difficult or seen as weakness for a man born in his generation, so he may feel the need to teach this to his children as well by raising them harsher rather than nurture.”

As Sonny struggles against a simultaneous resistance to and need for vulnerability, Hajoon and Hana wade through the muddy waters of grief in their own ways. Hajoon deflects the ache of the loss and attempts to focus instead on how to better fit into his new life in Canada. Hana, unable to accept that her mother is gone, spends her days making a wish for her return every time a plane flies overhead. The misunderstandings among the family build up, placing them further and further out of one another’s reach.

“I never wrote the film imagining grief would become such a central theme. I understood loss was a mutual experience that the family was undergoing, but wanted to focus more on each character’s unique situations, perspectives, trials and tribulations,” Yoo says. “Later, I realized that grief actually further drives them into their own worlds of isolation, as they all need to cope in different ways apart from one another.”

It isn’t until the film’s end that this period of isolation finally lets up, making way for familial understanding and reconnection. In two intensely vulnerable moments, the pain in Hajoon’s eyes and depth of loss in Hana’s voice help Sonny realize that his children both harbor the same hurt that he had been hauling all on his own. After tirelessly attempting to protect them from the pain as well as protect himself from having to admit the reality of his own, Sonny is finally able to understand his own loss in the context of his children’s, and the three of them are gifted with the relief of knowing they will never have to shoulder that pain alone again.

Strength in Visual Storytelling

Yoo splits this film into three distinct, character-driven chapters, utilizing both narrative and visual storytelling to paint a picture of the Lee family as they reshape their lives around the family’s missing matriarch.

“We wanted to cater the visual language in a way that really, really depicts each character’s perspective,” says Yoo.

Beginning with Sonny’s chapter, the screen is made to feel like a confined box where Sonny grapples with his grief. The walls close in on him as he fails to be the father he knows he needs to be.

“In the first chapter, the aspect ratio is the tightest, and the movement is also very jarring in a handheld way. It’s meant to evoke a feeling of suffocation,” Yoo says.

Like his father, Hajoon struggles to fit into the context of a new world, away from Korea and without his mother. Notably, Sonny’s perspective closes in from the sides of the screen, and Hajoon’s from the top and bottom, indicating the subtle differences in their inward battles, as both cope with the gravity of their losses in their own ways.

In the film’s final chapter, which captures Hana’s perspective, the aspect ratio expands to fill the entirety of the screen. It is a liberating effect after the condensed nature of both Sonny and Hajoon’s chapters.

“Everything’s captured wider to bring in a lot more of the world around her, so that we can see a girl in a natural habitat, with this naive lens of how she looks at the world optimistically,” Yoo explains.

Mongrels‘ toggling of aspect ratios effectively places the audience in the mindframe of each character. The technique is a result of the combined talent of Yoo and Vancouver-based cinematographer Jaryl Lim. Together, the two develop a very strong visual narrative throughout the film.

Notably, Mongrels often takes on a very surreal and atmospheric feeling throughout, with soft colors, blurred edges, and moments of stillness creating a sort of daydream effect. Each chapter has a unique feel to differentiate the character’s individual struggles, but this surreal aspect that underlies the entire film works to unite their separate parts in the same hazy sense of unreality inspired by deep loss.

“The visual language — whether aspect ratio, character focused chapters, and surrealism — was all intentional to paint each character’s unique experiences and world,” Yoo says. “I can only hope that it served each character well and did its job in allowing the audience to connect deeper and intimately with these characters.”

Explorations on Identity

Yoo often centers his works around Korean culture, placing an emphasis on the question of identity in relation to one’s background. Mongrels is no exception, as the characters work to understand their newfound identities as Korean-Canadians – an experience not too different from one that Yoo faced growing up as a member of the Korean diaspora in Canada.

“Growing up, I really wanted to know what it was like to be Korean, or what it would have been like if I grew up in Korea…” Yoo explains. “I’ve just used filmmaking as a vehicle to explore these ideas and thoughts.”

In Mongrels, Yoo takes us through the different manifestations of what embracing a new identity might look like. Sonny doesn’t wish to assimilate at all, Hajoon desperately tries to, and Hana does so without really realizing what’s happening. Each of them presents a different answer to the question of identity, while simultaneously pointing to the fact that there might not really be one right answer. What is clear, though, is that identity is a complex thing, woven deeply within the personal — especially for Yoo, who admits to having embedded much of himself into the heart of this film.

“[There’s] little pieces of me in every single character,” Yoo says. “[I had] the realization that I needed to put something so personal into a film of mine before I can move on to something that’s completely separate.”

Whether one resonates most with the film’s meditations on identity, or comes away with a better understanding of how to parse through the complex emotion of grief, Mongrels holds a lesson for anyone looking to understand how our emotions connect us to one another, and how this connection is one of the most valuable ones we may come by in our lives.

Ω