Photographs by Jim Bennett/Photo Bakery for the National Nordic Museum

Yet introducing new ways to explore such sensory delights is Fischersund, a Reykjavik-based family perfumerie and artist collective that includes siblings Jónsi, Inga, Lilja, and Sigurrós. In Faux Flora, their latest interdisciplinary display on view at Seattle’s National Nordic Museum, the collective creates a world of imaginary flowers using words, images, sound, and performance – while drawing upon strengths of human connections and family along the way.

Faux Flora is presented as “an exhibition in five parts,” and those five parts mirror the life stages of birth, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and death. Upon entering, one sees a warning that the exhibition has low visibility to enhance the effect of its digital imagery, presented using light panels, and that those with fragrance sensitivities may need to take precautions due to the use of “aerosoles tinctures and solid perfumes.”

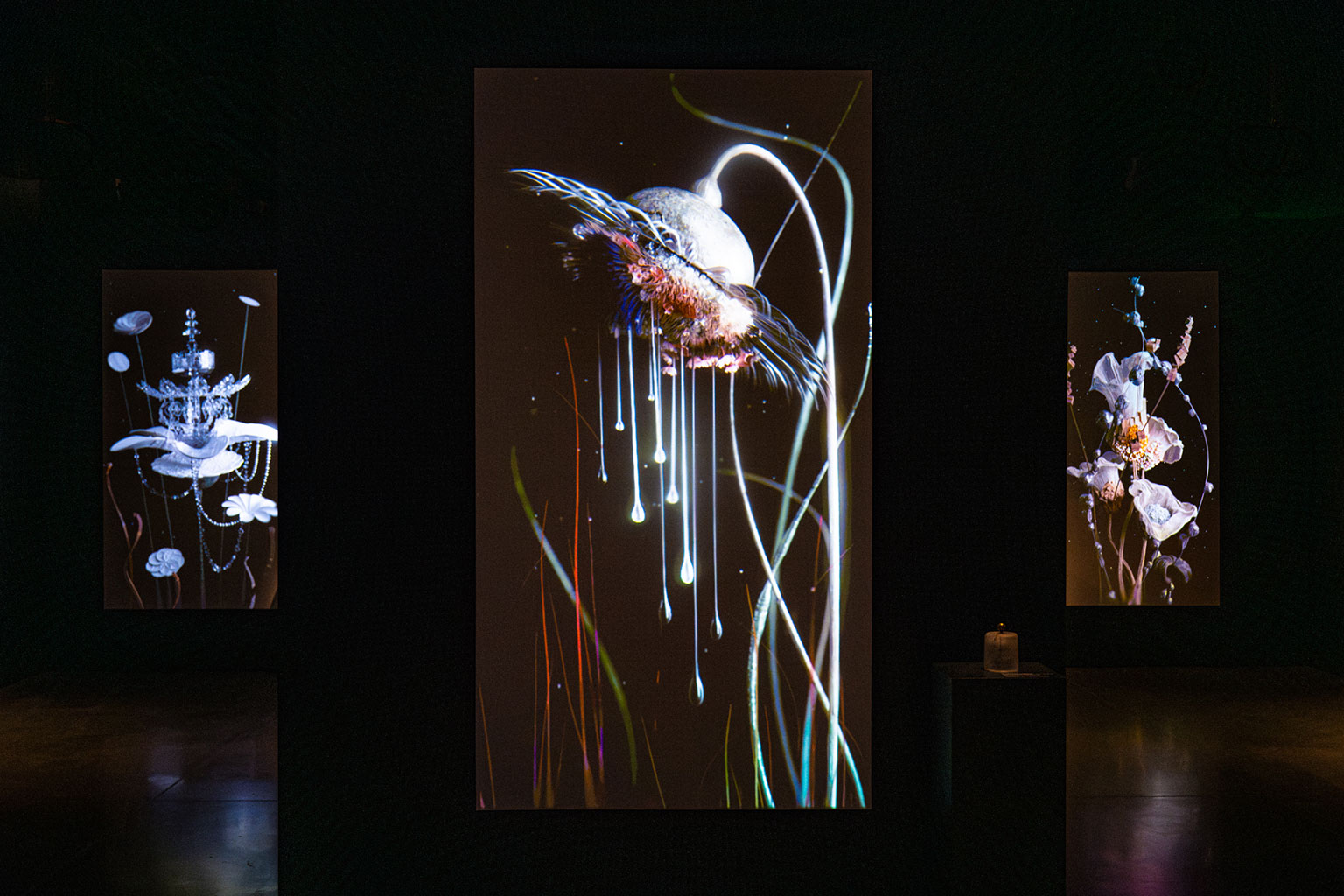

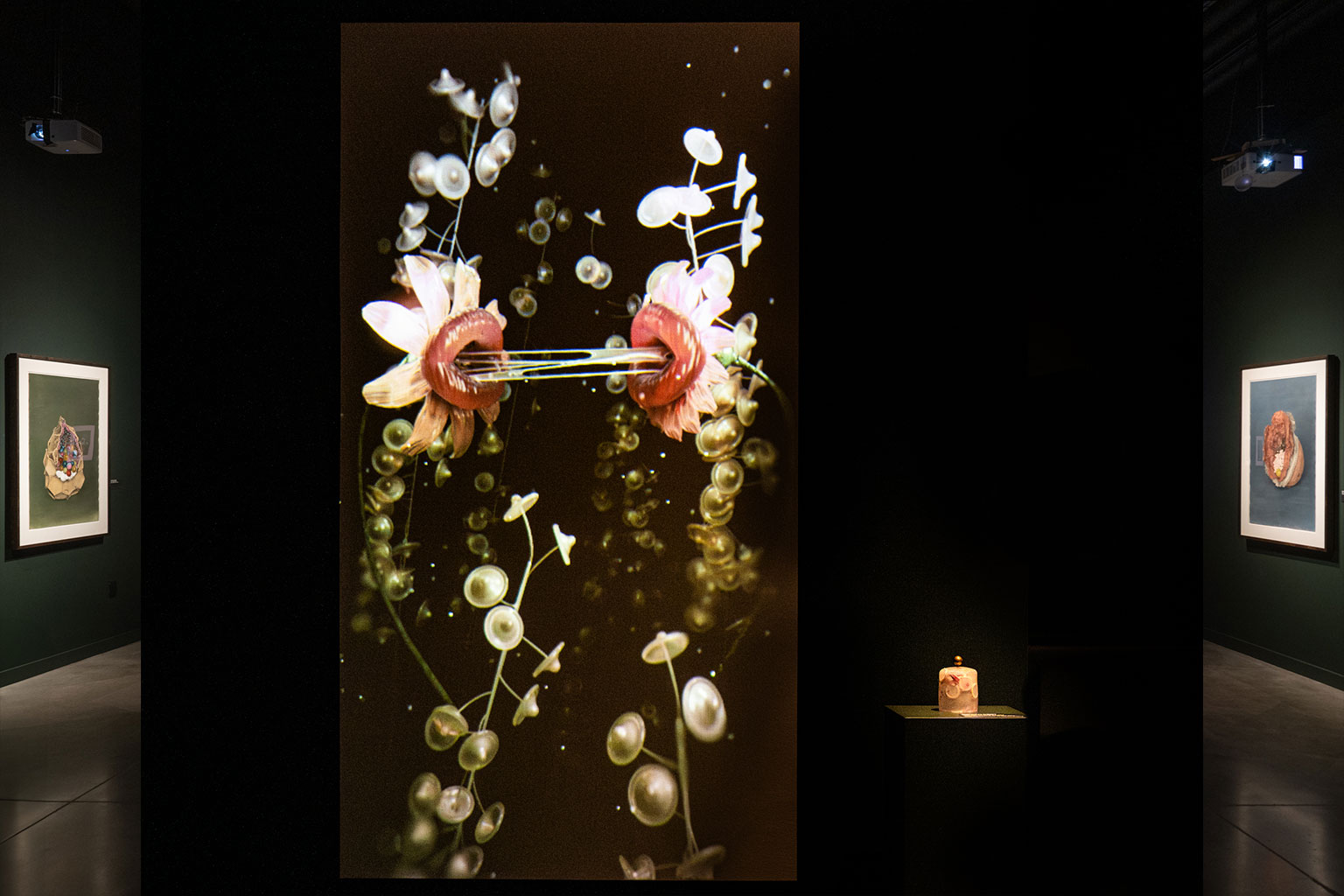

Such warnings may seem intimidating, but the high quality of the perfumerie’s materials seems to evade the worst possibilities of fragrance sensitivities. Those who dare to enter will be rewarded with a complex and multi-layered experience. Large, three-dimensionally rendered fake flowers are presented as video loops, then paired with a cornucopia of scents that, shockingly, smell very much like the images – and are further bolstered by matching, poetically-descriptive titles.

One is immediately greeted in the “Germination / Birth” stage with the first three-dimensionally-rendered fake flower, which is Fiallamiólk (Mountain Milk). Thick beads of milky substance drip down the sinewy edges of white-pedaled flower that looks something akin to a wide-open daisy yet has a milky fountain rippling upwards at its center. At its side, a plaque in Icelandic and English poetically describes the floral as, “White porcelain mountain milk flows from watery lips.”

The exhibition begs visitors to experience this scent poetry for themselves by lifting a thick resin container full of scented substrate to their noses. And here the first marvel unfolds: the scent is indeed milk-like, sweet and light but not too airy.

With this teaser in mind, one begins to get a sense of where this gallery journey will take them. Looking at the other imagery flowers down the line, one can’t help but be a little delighted to uncover þlotter (Laundry), which is described as, “out of cotton cloud curtains beam of light breaks,” and Slímtappi (Mucus Plug), which is “a diverse string of saliva beads embrace soft skin.” At the same time, maybe one is weary to experience Sog (Suck), which has a fragrance reminiscent of “rubber comforters soothe pearly prickly seedlings.”

Fascinating enough, sound is present alongside each video piece, but because they are presented via speakers and not headphones, they can become lost in the general ambiance of the entire room. It is easy to zero in on the individual scents and descriptors, but for sound, one must pay close attention. The effect of noise pollution comes into special consideration later, when one reaches the exhibit’s final piece.

For the Nordic Museum’s Chief Curator, Leslie Anderson, what sticks out is the collective’s ability to work with one another fluidly. She describes that each member has their areas of expertise, with Inga and Lilja working on visual art, Jónsi on sound and olfactory art, Sigurros on mixtures of the fragrances, and Albie on poetry, and Sindri and Kiartan collaborating with Jónsi on sound art.

“The artists each have their areas of interest and expertise clearly defined. Yet their work fits together perfectly, synthesizing into a cohesive multisensory experience that expresses the key ideas of the exhibition,” Anderson explains. “With major decisions, they listen to each other’s opinions, they reach a consensus, and they move on. As a curator, it was easy for me to propose ideas or offer feedback because of this harmonious, respectful, and supportive dynamic.”

In the show’s next phase, “Growth / Childhood,” one finds a series of hand-colored gelatin prints featuring flowers springing out of the packaging of nostalgic food objects, such as a Orvillle Redenbacher popcorn jar, Pik-Nik shoestring potatoes can, or more. Their coloration matches the intention: slightly retro and faded; something just a little bit off but close enough, like memories which one remembers only partially.

On larger monitors, one is presented with other imaginary flowers on loop. Bland ípl poka (Pick ‘n’ mix), rather sweet, is reminiscent of gummy bears and gelatin, as it tells us “the air melts like cotton candy, an explosion in the mouth.” The polar opposite scent is mirrored across the room; quite abrasive, Skráma (Skratch) features a flower with pedals made of band-aids, described with “sing loud bruises scratches Band-Air patches.” It is not necessarily pleasant, but what would Childhood be without such displeasure?

In the stage of “Flowering / Adolescence,” one is again greeted by hand-colored silver gelatin prints, but they take on physical characteristics of blossoming that seem to hint at the adolescent growing-into of oneself. Birth – Seedpod and Adolescence – Seedpod, are perhaps the most obvious of these, reminiscent a bit of vaginal body parts.

The stage of “Seed Formation / Adulthood,” the creators tell us, is intended to show a growth of responsibility and expansion in infinite directions. As such, each imaginary flower’s video loop shifts to take on more mature representations. Sparistell (Fine China), is crystalline, presented as an “illuminated room bathed in golden ambers, glitter on dusty glasses.” With Geymsla (Storage), the floral seems to be constructed of a mish-mash of random objects found in the remnants of an attic, described by Fischersund as “cedarwood walls shed glistening resin tears.”

Throughout the exhibit taste and smell and touch and texture are woven together in impressive and mind-expansive ways. Nature is ever-present, and that is also present in the exhibition’s final piece, Sunibruni (Field Fire), which is set in the stage of “Seed Dispersal / Death.

The video piece features the exhibit’s most prominent use of sound, as one watches gyrating waves of grasses that seem to be floating up a dark and tar-like lake of water. Undergirding this is drops of blood-like organic matter, paired with a score that is at moments celebratory, as it reaches an orchestral swell, and at moments haunting, as it decays into just slightly dissonant ambient.

“[Sunibruni (Field Fire)‘s] soundscape is intended to be heard from the entrance of the exhibition, reminding us that the exhibition will take us on a linear time-bound journey,” Chief Curator Anderson explains. “While many visitors will connect their personal experiences with the phases of life represented — birth, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, we have not yet experienced death ourselves. However, we may have lost people close to us and the memories and emotions of that experience are evoked by the sights, sounds, and scents of that chapter.”

“My father died eight months before the exhibition opened,” she continues. “When we installed Sunibruni (Field Fire), the somber multisensory experience — especially the melancholy music — gave artistic expression to my all-encompassing feelings of grief. It was stirring in a way that made me feel connected to my father, and it was cathartic… I have never had such a powerful emotional response to a work of art.”

The poem on the wall next to the video describes the sensation amply.

A dead vessel that once held life

how returning to earth

Preparing new ground

The farewell dance

The last dance

Seed dispersal

wilt wither die

become everlasting

Immortal

Ω