Karen Knorr

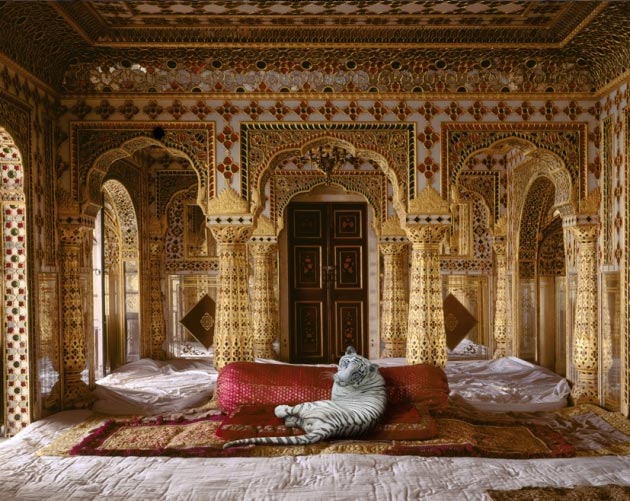

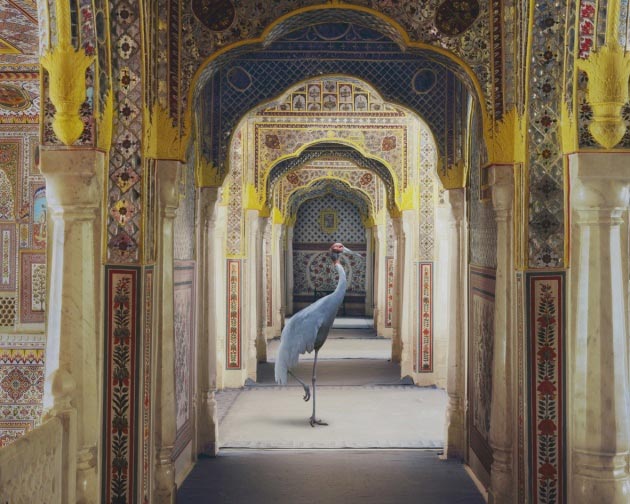

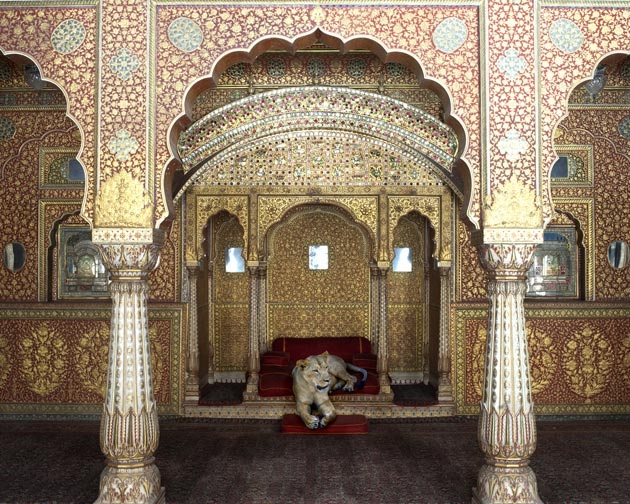

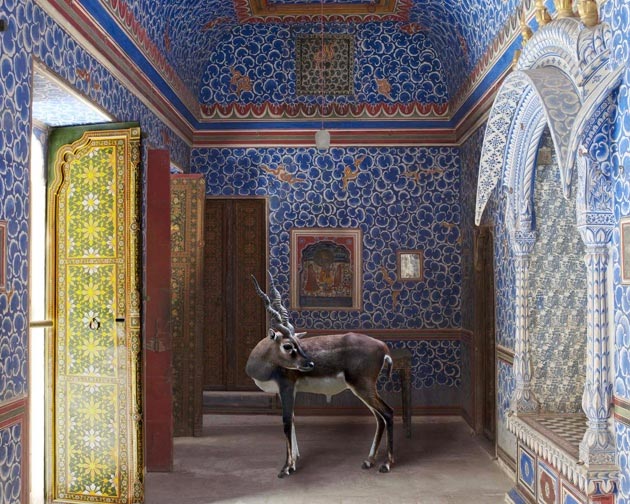

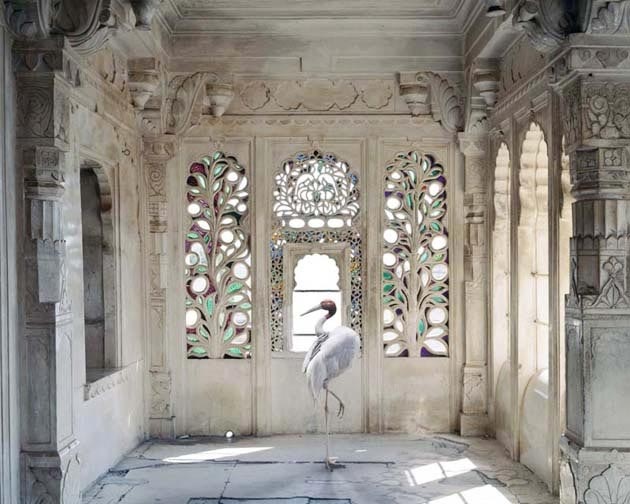

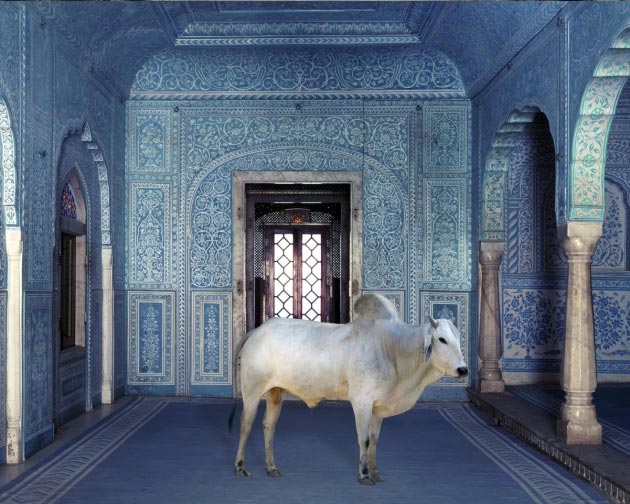

In Karen Knorr’s India Song series, she digitally inserts rare and wild animals, from cranes and tigers to elephants, in ornate north Indian buildings.

Where Yun-Fei Tou’s appeal to human nature is more obvious (below), Knorr’s is more veiled and steeped in cultural knowledge. According to her website, “The photographic series considers men’s space (mardana) and women’s space (zanana) in Mughal and Rajput palace architecture, havelis and mausoleums through large format digital photography.”

Yun-Fei Tou

For his Memento Mori series, Taiwanese photographer Yun-Fei Tou has taken over 40,000 portraits of dogs just hours away from euthanization. By seating the dogs in upright, human-like positions, they become almost human-like, giving viewers more to relate to.

“I believe something should not be told but should be felt,” says Tou, in an interview with Huffington Post. “And I hope these images will arouse the viewers to contemplate and feel for these unfortunate lives, and understand the inhumanity we the society are putting them through.”

Tou’s statement on the Memento Mori is the following:

Utilizing the classic portrait style that originated in the early 19th century with the birth of photography as an art form, these photographs offer the viewer a chance to look attentively into a bleak future. These dogs are essentially dead and their souls are hours or minutes away from non-existence. These portraits reflect a formal construct or platform through which the viewer and the dog communicate, using exchanged gazes to create a forced contemplation.

Photographic images allow us to contemplate. Through contemplation, we gain an understanding of the uniqueness and nobility of life. Through contemplation, we understand how chaotic and disordered the world has become.

The moment when a photographer chooses to release the shutter during a shooting session, or when carefully selecting an image from a body of work about the same subject matter, these acts, the releasing of the shutter and the editing of a selection, lead to subjective choices and reveal a bias. In the same token, every viewer has an inborn nature that is unique and possesses personal experiences that also reflect different values. Therefore, when different viewers face the same image, it is inevitable that they produce wide ranges of responses from the minute to radical to drastic differences in sentiment, interpretation, meaning and/or intent.

However, from the point of view of the subject portrayed in a photograph, these biases, prejudices, and even different sentiments can be perceived as a form of manipulation. It is often times these distortions and/or misinterpretations that offer richness in the various degrees of reality. The photographic image is merely a vehicle of communication that can lead to a better understanding of a situation, an event, of ourselves and of the world around us.

In viewing these specific images, one looks directly into the eyes of the dog and the dog looks back. These images reflect the last opportunity to look. This is a final and decisive moment. Death is eminent and all that is asked of the viewer is to engage, to recognize the common bonds and to honor the resemblances between our lives.

Knorr’s statement on the series is as follows:

Karen Knorr’s past work from the 1980’s onwards took as its theme the ideas of power that underlie cultural heritage, playfully challenging the underlying assumptions of fine art collections in academies and museums in Europe through photography and video. Since 2008 her work has taken a new turn and focused its gaze on the upper caste culture of the Rajput in India and its relationship to the “other” through the use of photography, video and performance. The photographic series considers men’s space (mardana) and women’s space (zanana) in Mughal and Rajput palace architecture, havelis and mausoleums through large format digital photography.

Karen Knorr celebrates the rich visual culture, the foundation myths and stories of northern India, focusing on Rajasthan and using sacred and secular sites to consider caste, femininity and its relationship to the animal world. Interiors are painstakingly photographed with a large format Sinar P3 analogue camera and scanned to very high resolution. Live animals are inserted into the architectural sites, fusing high resolution digital with analogue photography. Animals photographed in sanctuaries, zoos and cities inhabit palaces, mausoleums , temples and holy sites, interrogating Indian cultural heritage and rigid hierarchies. Cranes, zebus, langurs, tigers and elephants mutate from princely pets to avatars of past feminine historic characters, blurring boundaries between reality and illusion and reinventing the Panchatantra for the 21st century.

Ω