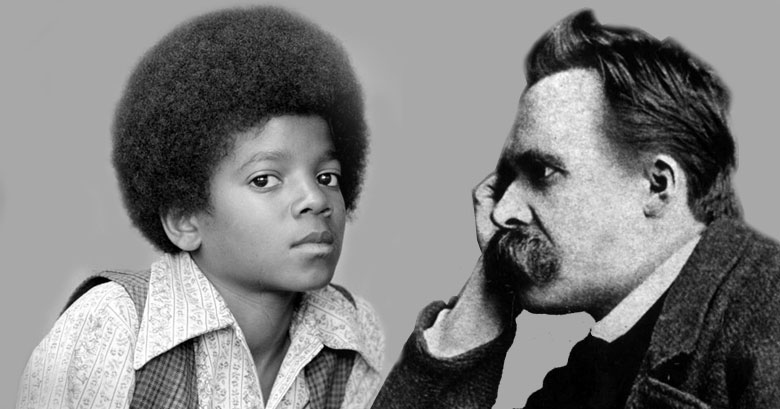

In an interview about the experience, Garrett noted that she “wanted to write a song that made him feel like he had something to say to the world,” the implication being, something of philosophical or spiritual substance.12 This statement in and of itself is fascinating. Jackson can be understood here as someone who captured the imagination of a generation to enough of an extent that giving him a message seemed an important and valuable act. There is an acceptance in this statement of the prophetic role of the pop star, the celebrity capable of carrying an inspirational message much further than a normal man. This puts Jackson at least somewhat in line with Zarathustra. As a philosopher who envisioned a higher possibility for mankind than anything he saw around him in his time, Nietzsche’s gaze was always directed boldly into the future. Accordingly, he clearly took delight in being able to craft the character of Zarathustra, an eloquent prophet who likewise took his insights culled in solitude and brought them bravely into the public sphere.

Jackson’s particular breed of propheteering had all the vivacity of Nietzsche-via-Zarathustra, though using the sexy and accessible medium of pop, he reached a much broader audience contemporaneously than Nietzsche’s writing (not only Zarathustra, but really, his entire canon) ever did in his own lifetime. A thrilling piece of evidence about Jackson’s inner life actually surfaced extremely recently: a work which feels, in retrospect, like a prophecy. CBS News reports that way back in 1979, when MJ was just 21, he wrote a manifesto detailing his life’s purpose — handwritten on the back of a tour itinerary. He wrote: “I should be a new, incredible actor/singer/dancer that will shock the world… I will be magic. I will be a perfectionist, a researcher, a trainer, a masterer… I will study and look back on the whole world of entertainment and perfect it, take it steps further from where the greats left off”.13 Even at a tender age, he conceptualized — and went on to realize — a grander possibility and greater scope for himself as a pop star than any who had come before.

I’d also point to two more details relevant to Jackson’s mode of prophecy. The first is a quote from Jackson taken from a 1982 interview about his passion for acting: “I always hated the word acting—to say, ‘I’m an actor.’ It should be more than that. It should be more like a believer”.14 The second detail is the closing imagery from Jackson’s music video for “Black or White,” in which a series of faces, spanning myriad racial backgrounds, all morph out of one another, all possessed by Jackson’s voice. Jackson was a believer. Even on the stage of pop, where the line between performance and reality is often indistinguishable, he made his work a testament for a more advanced future. In the case of “Black or White,” it was the belief in a post-racial society in which innumerable cultural understandings could be embodied within a singular individual. It’s that Nietzschean affirmative mode once again, in which multiple interpretive frameworks are available to be tried on for size in various situations, without concern for limiting oneself to a single, “absolute” system.

Shared Tragedy: “They Do Not Know Where My Centrum Is”

To subject one’s core philosophical and emotional beliefs to intense scrutiny is an intensely difficult process. As discussed earlier regarding the “Camel” stage, Zarathustra considers such scrutiny to be virtuous and absolutely essential to growth, yet he never hesitates to note that it is work which requires an exceptional level of strength. Not everyone is up to the task. Furthermore, the individual who lives so courageously runs the risk of being misunderstood — or worse yet, feared — by those who would prefer not to meddle with the comfortable and comforting structures they’ve always upheld. This is where the affirmative side of “The Man in the Mirror” finds its opposing parallel in a specific parable in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, entitled “The Child with the Mirror.”

This incident occurs during a time in Zarathustra’s career as a prophet where he has returned to his hermit-home in the mountains, thinking in seclusion following a spell in public. Zarathustra has a dream in which a child comes to him and holds up a mirror, urging him to gaze into it. Instead of seeing his own reflection, he sees the image of a devilish monster. Zarathustra awakens from the dream with newfound resolve to articulate and spread his message, interpreting the dream thusly: “My enemies have grown powerful and have distorted my teachings until those dearest to me must be ashamed of the gifts I gave them”.14 Jackson was extremely familiar with this situation of facing slanderous distortion in the public sphere. Nietzsche himself was likewise familiar with it in his own life. This is a point where Nietzsche’s own biographical details echo through the text of Zarathustra.

For both Nietzsche and Jackson, thorough alienation from society was two-fold. On the one hand, some of it was self-imposed. Both figures spent much of their personal lives in seclusion, and neither felt any real compulsion to mask or bury what others might view as idiosyncratic behavior. Yet on the other, their subversion — in behavior for Jackson, in thought for Nietzsche — ultimately made them targets for rumors aimed to degrade their credibility. In 1887, Nietzsche wrote in a letter to his friend, the musician Carl Fuchs, that, “In Germany they are crying out aloud against my eccentricities. But, as they do not know where my centrum is, it is not easy for them to hit the nail on the head in their efforts to determine where and when I have been ‘eccentric’ in the past”.15

To speak of an individual as “eccentric”, or off-center, displays an extremely narrow definition of normal behavior — an idea that would’ve been far too limiting for Nietzsche, the Dionysian. The same could be said for Jackson. The public hardly knew what to make of the plastic surgeries that radically changed his appearance beginning in the late ’80s, or his adoption of a pet chimpanzee Bubbles, who seemed to become one of his closest friends. While Jackson expressed genuine hurt about being labeled “Wacko Jacko” in the press, he was also known to have planted bizarre stories about himself in the tabloids, which could only have encouraged that label.16 Jackson was clearly a man possessed of his own “center,” though even in retrospect it is a bit difficult to articulate how that center functioned.

Sources

12 Garrett, Siedah. Interview for report: “The Woman Behind ‘Man in the Mirror'”. CNN. 29 June 2009.

13 “MJ’s ‘manifesto’, penned in 1979”. 60 Minutes Overtime. CBS. 19 May 2013. http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-504803_162-57585206-10391709/mjs-manifesto-penned-in-1979/

13 Jackson, Jackson. Interview with Bob Colacello. Interview Magazine Oct 1982: n. pag. Web. 7 November 2011.

14 Kaufmann, Walter, ed. The Portable Nietzsche. New York: Viking Penguin, 1954, 195.

15 Levy, Oscar, ed. Selected Letters of Friedrich Nietzsche. London: Heinemann, 1921.

16 Taraborrelli, J. Randy. Michael Jackson: The Magic and The Madness. Pan Books, 2004, 355-361.

Wonderful and thought provoking article. Thank you!

wow! Fascinating! I really appreciate the ideas presented by this article.

Great article! You saw and highlighted the core, most important things in Jackson. Fascinating parallels. Thank you!

Very insightful article shedding light on the motivations of two great artists.

Thank you. A really thought provoking article that connects the dots for me for MJ’s life, philosophy and art. I believe that his creativity was unparallelled in pop music and culture. He challlenged us and himself in ways that only now are being realized, studied and analyzed. Thanks again for adding to this discussion and apprecation of his life and work.

[…] http://www.redefinemag.com/2013/myth-of-michael-jackson-friedrich-nietzsche-the-child-in-the-mirror/ […]

[…] Gina Altamura’s The Child in The Mirror: A Nietzschean Reading of the Myth of Michael Jackson […]