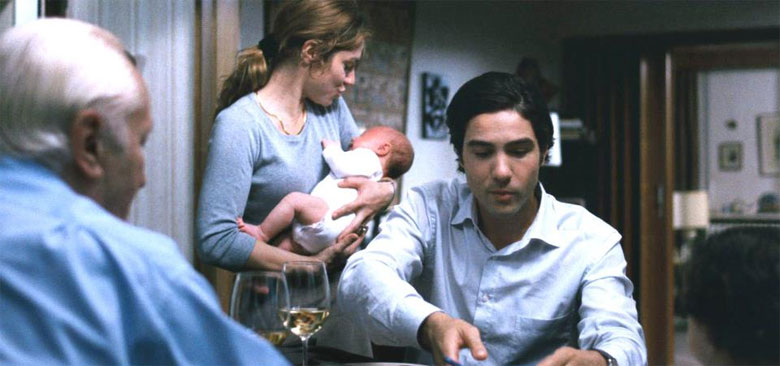

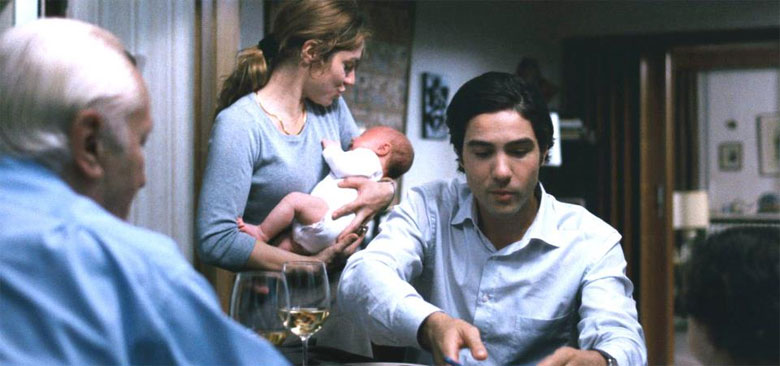

Shortly thereafter, after a series of strange communicative moves between all parties, the young couple move in with the man, and, in yet another awkward bout of communication, reveal to him their plans for marriage. The older man voices pleasure though it is known to the audience he is rather dissatisfied; nonetheless, he offers to pay for the couple’s honeymoon because they can’t afford it. The couple naively invite him to join in on their honeymoon as thanks for his generosity, and he accepts, thus cementing a bizarre and inappropriate relationship triangle. Years pass and they all continue to live under one roof. One-by-one, four children enter their lives, adding pressure and taking up more of the already difficult-to-find space, as the three adults become more and more entangled and volatile in their treatment of one another.

Shortly thereafter, after a series of strange communicative moves between all parties, the young couple move in with the man, and, in yet another awkward bout of communication, reveal to him their plans for marriage. The older man voices pleasure though it is known to the audience he is rather dissatisfied; nonetheless, he offers to pay for the couple’s honeymoon because they can’t afford it. The couple naively invite him to join in on their honeymoon as thanks for his generosity, and he accepts, thus cementing a bizarre and inappropriate relationship triangle. Years pass and they all continue to live under one roof. One-by-one, four children enter their lives, adding pressure and taking up more of the already difficult-to-find space, as the three adults become more and more entangled and volatile in their treatment of one another.

In addition to the interpersonal element of the film, Our Children also seems to wish to offer cultural commentary on differences in culture-specific relationships to elders and to marriage. It moves back and forth from family-to-family and Morocco and Belgium in an attempt to drive home this point — but this idea, while very central to the narrative of the film, only seems to have minimal impact. Though the film is never boring and the main characters do a fine job or portraying a relationship’s shift from bliss into tragedy, there is ultimately something that leaves viewers wanting more. The extent to which the characters cannot communicate or help themselves is unrealistic, in way that is not even frustrating, but ultimately just devoid of emotionally-invested interest. Suspension of disbelief always feels just a bit out of reach.

Directed by Joachim Lafosse

This film was reviewed for Seattle International Film Festival 2013.

Ω