Multi-disciplinary artist Chad Wys is all about tricks of the eye that then tickle the mind. Whether by splotching paint on fine porcelains or enhancing vintage reproductions with pixel paint, his works live within a blurred space between the digital and the analog, via additions that also subtract — or subtractions that also add.

“Increasingly, I’ve begun to disregard the boundaries between the analog and the digital, between the physical world and the Internet,” says Wys. “I mean, quite literally there are differences and boundaries that separate the Web from the physical space where I do much of my analog work, but intellectually and philosophically, I think the two realms overlap more they distinguish themselves from one another, particularly where the conceptual content of my work, my process, and my methodologies are concerned.”

Color is Wys’ primary tool and thrift store objects are his irreplaceably unique canvasses — and one need look only to his long-standing readymades series, which he began in 2009, to understand that the aesthetics which thread through his work are both unified and quite disparate. Every block of color, every well-spaced line, and every speck of glitter Wys endeavors possesses rich associations that run deeper than their simplistic look. His choice of objects, which are simultaneously kitschy and classy, are merely the outwards face of these associations, which extend backwards into his personal artistic history as well as ever-forwards in his evolving philosophical approach. To be fair, one can arguably make such connections in the work of all artists, but with Wys, these connections are particularly well-pontificated, well-articulated, and readily accessible, as he evidenced in the following interview.

Since youth, I’ve responded to color in profound ways. I can recall being quite young — six or seven, perhaps — and being deeply moved by the Impressionists’ use of formless bits of color. They used it in intense ways, with vibrant explosions, and they used it in minimal ways, with entire canvases of sedate pastels. That was transformative for me; it was a beauty and it was an experience that rattled me. My experience of art at that age influenced the course of my thinking and the trajectory of my life. I’ve been obsessed with color ever since. I think of it as my primary aesthetic instrument.

Indeed, on a superficial level, my methodology as an artist frequently involves introducing foreign color palettes to the materials I appropriate; doing so facilitates an entirely new conversation around the visual problem, or idea, that I bring to the fore. Sometimes all it takes is the suggestion of a particular color to manifest a work of art and to take on a complex array of critical meanings. Color is an aesthetic experience, in my mind, but it is also profoundly intellectual.

– Chad Wys, on his relationship to color

<! — more — >

What was the first readymades piece you ever experimented with? How did it come about?

The first I can recall is Thrift Store Landscape With A Color Test [which was completed in 2009]. It was an important event in my life because it introduced appropriation and stark minimalism to my repertoire; prior to that experience, I’d been painting relatively traditional, and fussy, abstract compositions and expressionistic landscapes. It was a turning point because it meant I could finally address so many of the philosophical concerns I’d been examining elsewhere, like in my academic work and in my writing. That really was the impetus: my experiences as a student, especially as a grad student earnestly studying art theory, visual culture, and art history.

I can recall having visited Goodwill and exiting the store with the massive framed landscape that would serve as the “canvas” for that readymade. I was fairly embarrassed because I knew how kitschy it was and I was concerned what others thought of this young man buying such an ostentatious decoration. That insecurity has since faded considerably. And although I was ultimately satisfied with the result of my first attempt, I recall being insecure, unsure of how anyone would receive it as an artwork. Years out, I couldn’t be more confident in that decision. My work has been more mature and more thoughtful ever since.

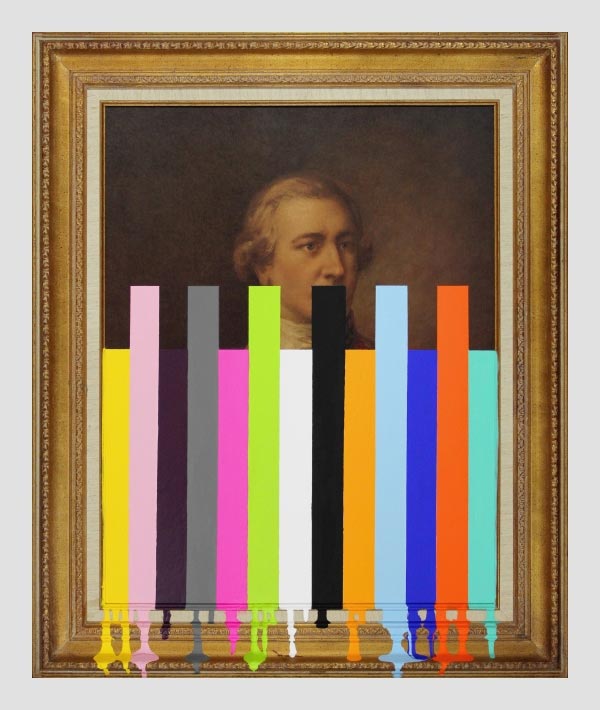

Thrift Store Landscape With A Color Test (2009)

Thrift Store Landscape With A Color Test (2009)

Throughout the years, you’ve used a lot of the same types of props and patterns in your readymades series. How, if at all, has your approach to it changed throughout this time?

I think my marks have become more confident over time because I’m more comfortable with imperfection. When I first started crafting readymades, I was relatively unsure and insecure about what marks to make, where, and to what extent. I feel more confident about appropriating materials that serve my conceptual framework, and I feel more confident about my process of intervening with those materials. I’ve learned to regard mark-making as a poetic experience — at times, unexpectedly quite moving. Applying paint to an object or an image with a presence and history of its own can be quite emotional, especially if I feel strongly about the material. At times, I can’t bring myself to make a mark. The marks have come to mean a great deal to me and I’m not always prepared to make them. But at the same time I face this occasional reticence, I feel more confident about my process overall precisely because I have these deeper and more elaborate feelings about my craft.

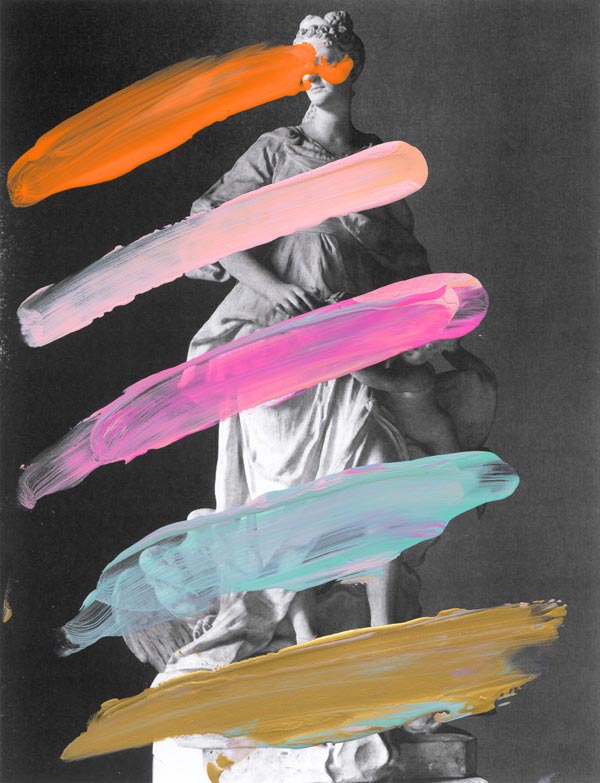

Sight Line (2013)

Sight Line (2013)

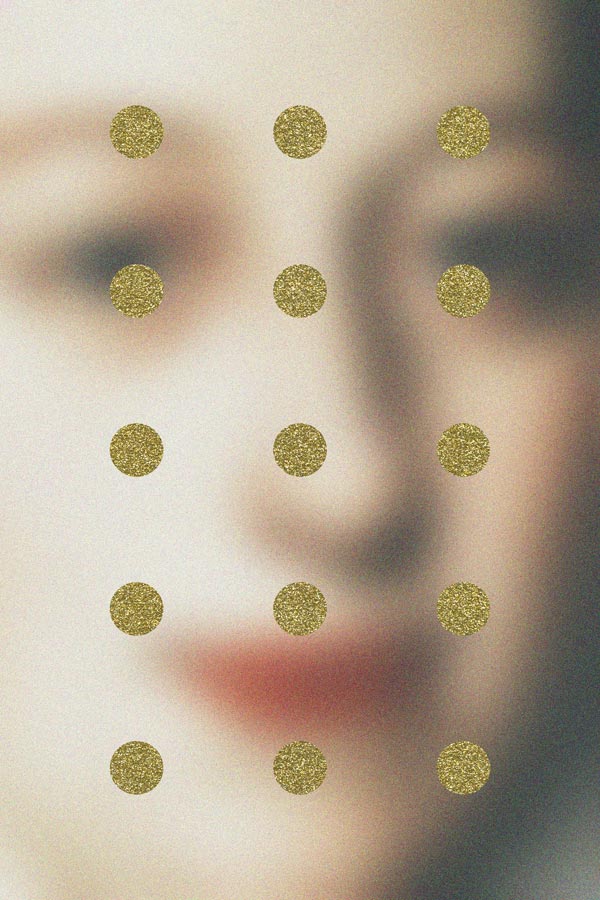

a pair of faces (diptych) (2013)

a pair of faces (diptych) (2013)

It is common in your work — and the work of many other artists — to manipulate the human form in ways that block out physical features, especially different aspects of the face. What do you suppose it is about creators that makes this such a recurring trend?

For many centuries, the goal of art making was to render the human form as faithfully as possible. Art was regarded as a window into the world, a great illuminator of the ultimate “truth” of human existence, a way to both capture and reveal the wonders of our world. This was always a lie, of course. There are no ultimate truths and there is no way to capture reality without imperfection. Once we attempt to depict reality, the depiction is tarnished by the intrinsic subjectivity of the attempt; be it an imperfect word that is selected to describe the human face, or an imperfect color to depict skin tone, an imperfect choice is made and the rendering is instantly a subjective experience (and historically presented as truth).

I think modernism, and to an even greater degree post-modernism, has been about the rejection of art as truth-teller. The necessity to capture a portrait precisely no longer intellectually exists because the value of such a rendering is seriously disputed by what we understand about ourselves and our world. A likeness is always inadequate no matter how skillfully rendered, and intellectually speaking, what is the achievement of rendering a likeness anyway? I think artists who impede the ability of a viewer to observe a would-be likeness are remarking on the futility of portraiture. Ostensibly, faithful portraits impart very little substance about their sitters, despite the feeling of a complete experience ground in the superficial/aesthetic. It’s a false kind of experience because we project many of our own experiences onto the observable likeness, sometimes fooling ourselves that the experience has been intrinsic to the familiar likeness. I think artists who eliminate visual clarity where the human form is concerned are reacting against, or for, or because of the artistic convention of likenesses. We artists like to eliminate clarity to draw attention to the absence of clarity in the first place, as well as the presence of a false sense of clarity that’s housed in the superficial.

Some of your work uses digital painting to manipulate existing reproductions of paintings. This is a dizzying thought. What do you find to be the appeal of this?

On a technical and aesthetic level, I enjoy conflating media. I like digitally replicating analog (wet paint) techniques, and, vice versa, I enjoy manifesting digital “copy and paste” methodologies in analog applications, like collage. I think there’s a great deal to be learned for each kind of medium, both virtual and physical. Appropriating a digital reproduction of an antique painting and proceeding to digitally alter it — with trompe l’oeil techniques that mimic the physical application of paint — potentially brings attention to the malleable nature of reproductions in general. Once something is replicated, it’s out there, being used in all sorts of contexts. Images lie; images tell confusing stories and obfuscate the journeys they’ve taken. In different hands and under different conditions, objects and images can impart vastly different meanings. This is why I appropriate in the first place: to draw attention to the reproductions that surround us.

My interventions with these replicas are merely my way of recontextualizing the conversation, or asking the viewer to consider the literal nature of what I’ve sourced, what they’re seeing, and, by extension, what they observe on a habitual basis; the Internet, and digital data, is ripe for this exploration of reproductions.

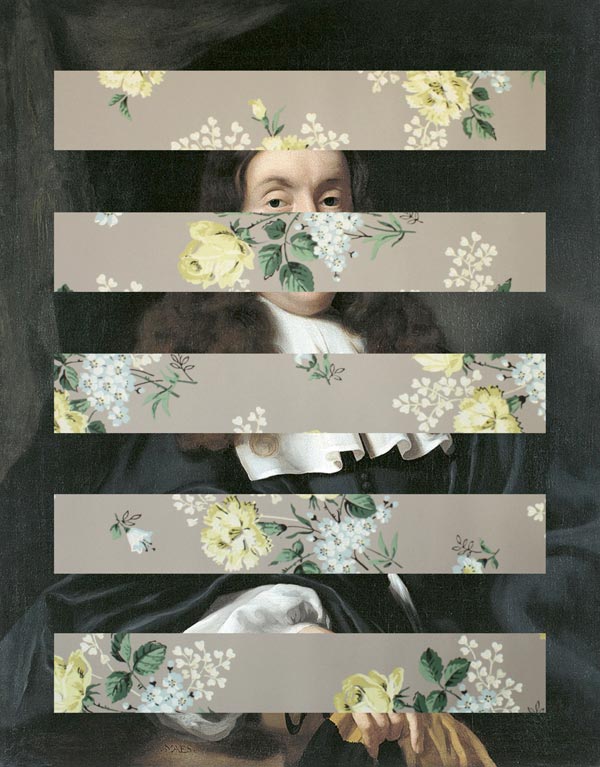

Select works from Chad Wys’ American Tapestry Series

Select works from Chad Wys’ American Tapestry Series

What do you find to be the major pros and cons for working in the digital versus the physical?

The digital work space generally offers an “undo” option, whereas the analog work space generally does not. I prefer the digital because I feel freer to experiment without the threat of an irrevocable accident, whereas in physical space the pressure to get things correct the first time is heightened… particularly when one works on relatively unique surfaces as opposed to a blank canvas. I think viewers tend to respond more favorably to analog work because of the mythical permanence, or the finality, of the material object, the existence of a concrete “original,” and because there is no “undo” option. Analog media requires a level of impulse and spontaneity that digital media transcends; and I think this is why I’ve found viewers preferring my material work, despite my personal preference for the digital. Viewers seem to favor the suggestion of artistic spontaneity (analog) over artistic deliberation (digital). I think analog media inherently offers that sense of spontaneity because paint waits to dry for no wo/man, it’s there and it needs to be manipulated quickly or else it’s useless. There’s no urgency with the digital because the digital is limitless.

The bulk of your work builds off of the past and found objects; do you or have you ever considered experimenting with only the present or future in mind? (If that makes sense.) Why or why not?

Although the referents in many of my works are aged and suggest art historical motifs, much of the material I source is literally contemporary in nature, or distinctly modern in their association with the industrial revolution. I generally source reproductions. It’s the reproduction I fixate on conceptually and I think reproductions are a contemporary concern. The way we receive and understand reproductions is at the core of my concern and at no time in history has our visual culture been more saturated with replicas or simulacra. Through my marks I intend to draw attention to our receptions of copies. The Internet has made the issue pandemic and constant. I like the juxtaposition of antique imagery and contemporary technology, or the idea of the mechanical reproducibilty of history.

My understanding is that a lot of your work is created on the fly, rather spontaneously. Is this true? Is this analogous to how you generally live your life? Do you have any personal rituals to help you get in the creative zone?

Aspects of my process are impulsive, but sometimes I plot out a particular project precisely before hand, even attempting to account for paint drips and the locations of those drips. It’s not uncommon for me to photograph a sourced object and experiment with various application in Photoshop prior to executing the physical work with wet media. However, often, especially where analog materials are concerned, the need for adaptation and spontaneity arises — as one cannot predict precisely how paint will react to every surface, and sometimes one is incorrect about a particular color scheme and modification ensues. I think my craft is equally about deliberation, impulse, and adaptation. Some projects are more dependent upon chance, where quick applications of media can cause spontaneous results, while other projects are more carefully deliberated, with every crop and every element strategically placed. I think I enjoy the hybridization of these methodologies best of all, when spontaneity and deliberation are brought together.

A work dependent on chance

A work dependent on chance

A work carefully deliberated

A work carefully deliberated

Your work has been promoted quite well through social media recently. Is this a sphere you devote energy to, or has this momentum been out of your hands?

I think social media is vastly out of any single individual’s control, but I think it’s possible for individuals to proactively engage and that can cause others to respond in kind. Years ago, I began by simply sharing my work online, and I was fortunate enough to be seen and shared. I think if I have any presence online it’s through word of mouth and through sharing outside of my control. I haven’t been very good at promoting myself because I don’t personally relish or seek the limelight. I’m likely the shyest person you’ll meet. The Internet has made it possible for me to come out from hiding, so to speak, and to share my ideas with a generally quite kind and generous audience. I’m honored every day when people care enough to share my work. I can’t tell you what a privilege that is.

You’re very interested in how your art affects others, and what kinds of meanings others derive from it. What are the types of reactions you hear most often? Are there any you find particularly surprising?

Much of the time I think people respond to the aesthetic I create with my marks and the materials I source. That can be quite a shallow reception, and I think it’s possible for the deeper concerns of my work to be missed for the bright colors and the effect/affect of the aesthetic. But to me, that’s also a hopeful and encouraging form of reception on the part of the viewer, because I think all art is first experienced superficially/aesthetically, and only later do we journey beyond our sensory experiences to a philosophical dialog (with oneself and/or with others).

I’m not easily surprised when it comes to the reception of art, but I am often taken aback when someone vehemently rejects my work. A frequent criticism is that I’ve stolen other artists’ work, or that I’ve “vandalized” something precious and beautiful. This is not in itself surprising — I shared similar responses to appropriation art when I was young, later to grow out of such dismissals and then outright embrace the methodology for my own — but I am upset by these sorts of reactions because I think they manifest out of fear and confusion (and I say that from experience with a level of respect). Obviously I haven’t actually “vandalized” an original Raphael oil painting; I’ve merely found a reproduction and proceed to draw your attention to it by reconstituting it as a new experience. The “vandalism,” if we should use such a term, might have taken place when the original painting was initially processed, produced, and manifested into an infinite array of replicas for disposable consumption.

A manipulation of a Raphael reproduction

A manipulation of a Raphael reproduction

As you have an interest in the role art plays within a capitalist society, as a luxury versus decorative good, etc. — what are your reactions to changing models of distribution because of digital technology? Do you view it as easier or more difficult to be a working artist in this day and age?

Oh, I imagine it’s infinitely easier. There are problems associated with the use of technology, like the Internet, to share and to sell one’s work — not the least of which is competing for attention among an enormous pool of an increasingly greater number of artists and amateurs (not that the distinction is worthwhile) — but the ability to share one’s work instantly, before the paint has even dried, with anyone, anywhere in the world is beyond advantageous… it’s a game-changer, and I think vastly for the better.

I’m excited about the Web and the bringing-together of disparate creatives from around the world. I think the future of art is going to be brighter and better than ever. Important thinkers from diverse cultures are going to be able to share ideas with one another like never before. It’s going to be a global art world rather than art worlds sequestered in a few key cities. Diversity is never a bad thing. Decoration vs. fine and high vs. low be damned.

Select works from Chad Wys’ Collage and Works on Paper Series

Select works from Chad Wys’ Collage and Works on Paper Series

Ω

[…] USA, Chad Wys grew up obsessing over picture books of 19th and 20th-century paintings. It was this self-confessed naïve fascination of art and the romance between art history and visual theory which motivated Wys […]