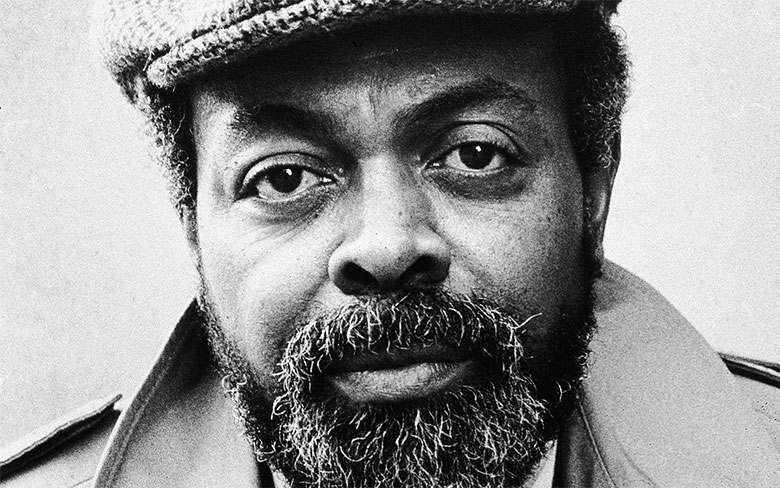

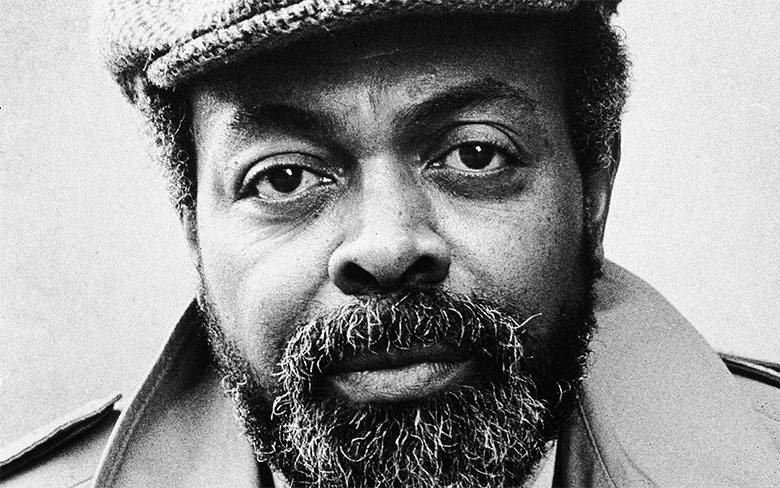

Amiri Baraka was an artist at the crossroads: between pre-war and baby boom; between black and white; between free-jazz and hip-hop. He stood between hippies, beatniks and black power; sci-fi and harsh realism. He occupied the intersection between humor and ugly truths. As we continue to lose more and more of the older generation of freedom fighters, we run the risk of forgetting – forgetting the struggle, and the oppression they were struggling against. As we get further and further away from slavery (the Southern kind, anyway), we are in danger of forgetting its face and losing sight of its specter, even if it’s only in our minds.The 20th Century was unique for being the first full century with recording technology. While we may not get the scent of tear gas on the breeze, or know the humidity of an August afternoon in Birmingham, we can strive to remember and understand through records, photographs and film.

Going through the recorded legacy of Amiri Baraka, from the ’50s through the ’90s, is like opening a time capsule. It reminds us of the revolutionary power of jazz, poetry and theater. In 2014, all of those forms have almost entirely been de-toothed and un-fanged, become a tool of the bourgeoisie that they panned, bombed and smashed. It’s easy to forget that these were the voice of the people. It calls us back to a time of street theater and community workshops: these were a time of action. Without this reality, it is all too easy (and dangerous) to co-opt the art of revolutionaries past, to bolster your own cred, while safe and comfortable in your air conditioned citadel.

The Black Arts Movement

The Black Arts Movement, also known as BAM or the Black Aesthetics Movement, was the artistic branch of the Black Power movement, first started in Harlem by Everett LeRoi Jones, or Amiri Baraka. TIME Magazine has described the movement as the “single most controversial moment in the history of African-American literature – possibly in American literature as a whole.”

The formal beginning of the Black Arts Movement was found in Jones’s establishment of BARTS, the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School. Participants in the movement subscribed to both militant and non-militant philosophies, and their work brought diverse and multicultural voices to the previously white-dominated literary scene, as well as inspired African-Americans to own publishing houses, magazines, journals, and arts institutions. It also led to the creation of African-American Studies programs in universities, which later had similar repercussions for other ethnic groups in the years to come.

These songs and poems and jams remind us to get involved, to know your neighbor, to care, about yourself and others. It teaches us to think and listen beyond genre, race and era, and remember we are all in this together; our survival depends on it. Perhaps, with his passing, we can regain an appreciation towards these 20th century forms, remember why they were revolutionary, what was great. Another benefit of recordings is they allow us to view objectively, without the grime of nostalgia, which is every bit as dangerous as apathy, if not more. With the passing of Amiri Baraka, it offers us an opportunity to look back and remember, and to wonder where we’re going. What works? What’s better? What’s worse?

Without recording technology, we might forget that Imamu Amiri Baraka, the man formerly known as LeRoi Jones, was full of Holy Spirit. When reciting his poetry, he was equal parts Martin Luther King Jr. and Chuck D. While Amiri Baraka was highly intelligent and educated, he spoke with a voice by and for the people. He stood at the crossroads between Academia and regular folks, between folk and the avant-garde. His work, his voice, his life, can help us to understand each other, and where we all came from, just a little bit better. In the poem “Leroy”, from 1969, Baraka wrote:

“When I die, the consciousness I carry I will to blackpeople. May they pick me apart and take the useful parts, the sweet meat of my feelings. And leave the bitter bullshitrotten white parts alone.”

What Amiri Baraka could not have predicted, when writing those lines, is that we are all inheriting his consciousness. We all carry his spark; we are all living in the world he fought and dreamed for.

Below are 10 recordings, from different phases of Amiri Baraka’s career, to help us remember and reflect.

To the family and friends of Imamu Amiri Baraka, you have our deepest sympathies. He was a great man, and will be deeply missed. He said a lot of things, boiled a lot of blood and ruffled a lot of feathers, but we are still listening, still thinking, still struggling.

1. “Black Dada Nihilismus”

This track was what got me into Amiri Baraka, by way of a DJ Spooky remix on the A Red Hot Sound Trip compilation, from 1996. It’s a surreal and sinister, stream-of-consciousness fever dream of African-American stereotypes, recorded with the New York Art Quintet. His incantations are neither polite nor restrained, galaxies beyond the safe formula of today’s “slam poetry”. This was recorded in 1967, right in the thick of things, and reminds us that there are REAL injustices to be railed against, and silence is the same as compliance.

“May a lost god damballah, rest or save us/ Against the murders we intend/ Against his lost white children/ Black dada nihilismus.”

2. Black Dada Nihilismus (DJ Spooky Remix)

We’ll include a couple of remixes, to illustrate the ways that Amiri Baraka have infiltrated hip-hop and remix culture.

Like the poet/MC Saul Williams said in his eulogy for Baraka in The Fader: “In our glorification of original gangstas and rebels how could we ever forget to glorify one of the most original voices of Black anger?

3. “Against Bourgeois Art” (featuring Air, 1982)

“Is there somebody here to record this?” Thankfully yes. This loose and scattered free jazz number with the band Air manages to be both a firebrand and super chill at the same time. It’s a perfect illustration of how Baraka can at once be both the voice of righteous indignation and completely hilarious. “Against Bourgeois Art” is a scathing, spot on criticism of “avant-garde” artists, assimilated into the system.

“They fight knowledge with abstraction and think they cool cuz they talk to themselves. They is full of shit, like vultures pecking on an open grave. They uphold capitalism, and give themselves airs. They think their shit is profound and complex, but the people think it’s profound and complex as monkey farts. Now, meditate on that.”

4. “Who Will Survive America?” The recent trend of reissues and archiving has done wonders for preserving the past, raising people’s interests through careful curation and superb packaging. This soul jam was included on the Black Power compilation Listen, Whitey, re-released on the impeccable Light In The Attic Records

.

“Who will survive America? Very few negroes. No crackers at all.”

5. “Bang Bang Outishly”

Baraka was known for his passionate writings on the subject of jazz, after working in a record warehouse in the East Village. “Bang Bang Outishly” is a poem he wrote on the subject of one Thelonious Sphere Monk.

Jazz was truly an American music, classical music constructed on the spot, in the heat of the moment. It was invented by, and most popular, among African-American musicians, and incorporated a lot of African elements, like call-and-response and unusual meter.

Baraka addressed this issue in the essay “Jazz And The White Critic”, in which he said: “Failure to concentrate on the blues and jazz attitude rather than his conditioned appreciation of the music. The major flaw in this approach to Negro music is that it strips the music too ingenuously of its social and cultural intent. It seeks to define jazz as an art (or a folk art) that has come out of no intelligent body of socio-cultural philosophy.”

Let’s take this opportunity to re-appraise this artform, to remember how far out and revolutionary it was, and try and appreciate it on it’s own terms, and hear what they’re trying to say.

…and here’s a remix, turning Baraka’s incantations into a sound poetry of their own, turning his words back into jazz…

6. “AM/TRACK” (Featuring Air)

Here’s another poem inspired by jazz, this one for the late, great John Coltrane.

Baraka described Coltrane in terms of modern painting, saying it reminded him of Mondrian’s geometrical decisions, calling it a “metal poem”. It remains some of the finest and most poetic writing on music you will ever read.

“Not only does one seem to hear each note and sub-tone of a chord being played, but also each one of those notes shattered into half and quarter tones…”

It is like a painter who, instead of painting a simple white, paints all the elemental pigments that the white contains, at the same time as the white itself.

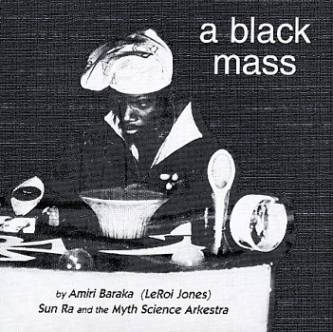

7. “A Black Mass” (Featuring Sun Ra and the Myth Science Arkestra)

http://www.pandora.com/amiri-baraka-with-sun-ra-myth-science-arkestra

This is a long, weird one, but well worth a listen. It details a critical position between free jazz, Black Power and science fiction, which laid the roots for a movement known as Afrofuturism.

This is a long, weird one, but well worth a listen. It details a critical position between free jazz, Black Power and science fiction, which laid the roots for a movement known as Afrofuturism.

Sun Ra, born Herman Blount, was an incredibly out there jazz musician, who claimed to be from Saturn and made hundreds and hundreds of records with his band, The Arkestra. He was an early adopter of electronic instruments, utilizing their ability to evoke images of outerspace. Sun Ra, like Amiri Baraka, was dreaming of a new world and better tomorrow for African-Americans.

on Sun Ra: Baraka: Well, Sun Ra was making a kind of free jazz. He was not just adhering to the kind of Tin Pan Alley legacy that most of the music has, and even the Be-boppers who were just using the harmonies rather than those same kind of melodies were still kind of linked to those kind of chord structures. What Ra said, and indeed all those musicians that came out during that time: Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, Pharoah Saunders, all those musicians, beginning with the late Coltrane, began to emphasize going beyond the kind of Tin Pan Alley structures, and it just seemed like Sun Ra was just doing it in earnest. He was trying to go as far as he could. But the music has very clear African, Asian, Latin kind of bases to what it is, although he’ll go off and play some sounds perhaps you’ve never heard or never heard associated with jazz, although if you have listened to most modern world music, you’ll certainly hear that, if you listen to Weber, Stravinsky, or somebody like that, or Bartok. What Ra was doing was trying to make a kind of cosmopolitan music past just the regular kind of night club be-bop.

Paulson: I’m curious, how has Sun Ra’s poetry and music influenced your own creative work, if it has?

Baraka: Well, Sun Ra certainly came in in a period where I think our generation was thinking similar kind of thoughts, whether it was Albert Ayler, or later Trane, or Ornette Coleman. We had similar kinds of ideas. First of all, transcending American society. And I thought there is a commonality in that, even the science fiction aspect of it was related to the fact that we wanted the society to change, and we were willing even to posit alternate models. I mean, Sun Ra speaks inconstantly of alterworlds, alterlife. Things that are not this way, parallel but different, you know.

Paulson: And I suppose where the whole science fiction legacy comes in, as well. Why someone who identifies with that science fiction tradition is a radical. I mean, you’re imagining newer and possibly better worlds.

– from the introduction to This Planet Is Doomed: The Science Fiction Poetry of Sun Ra (Kicks Books)

8. “For Amiri Baraka” (by Toki Wright) Let’s take a small break, and listen to the modern influence of Amiri Baraka, from MC Toki Wright.

“Will our children even be able to recognize the bones of their own timeline? Will the child’s eyes be blinded by screens, ears deafened to the screams, their feet weighed down by the newest pair of J’s on a race to the end? We have a responsibility to carry the fire, be it in our stomachs or on the end of torches. If you fear the person who cuts your check, you will never walk upright, cuz sharecropping is not an option. Don’t let these ships dock on your thoughts and colonize on your mind. Don’t let hip-hop get so lost it forgets the burning South Bronx, the massacre at Attica, the tumult of Jamaica, the back split open in the fields of Georgia, and the vast landscapes of Nubia.

9. “Someone Blew Up America”

We draw close to the end, with the poem that lost Amiri Baraka his Poet Laureate status. It was too soon, about a touchy subject. He was accused of anti-semitism, downright barbarism. He spoke the truth that he saw fit, the truth no one else would speak. He spoke hard truths, using poetry like a Molotov cocktails to light people up when they were flammable. You might not agree with what he’s saying, but you have to admire the grit.

10. “Rhythm Traveller”

Last but not least: a short story, about a man who can travel records, materializing wherever that song is played. We like to think it’s true, and Amiri Baraka’s spirit will appear where these songs may appear, to embolden us, to make us strong in our convictions. To make us try. To make us care.

“You can disappear, and re-appear, wherever that music is played. So if you become “black, brown and beige”, you can re-appear anytime and anywhere that plays. Like, I go into ‘Take This Hammer’, I can appear wherever that is, was, or will be sung. I turned into some Sun Ra, and hung around inside Gravity. You probably heard of the scatting comet? Hey brother, ain’t no danger. Just don’t pick a corny tune.”

Ω