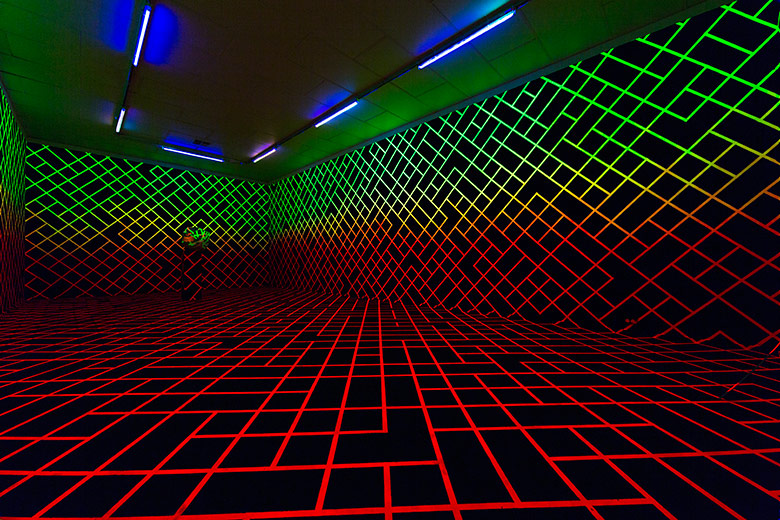

If the neon landscapes of Tron were to intersect with the real world and become fully infused with the spirit of modern electronic music, the output might look something like the 3-dimensional portals created by Australian artist, Sam Songailo. A transformer of gallery walls and public spaces into hypercolored explosions of pattern, Songailo first began exhibiting as a 2-dimensional painter in 2006. He discovered then that the canvasses he worked on, with all of their hard edges and limitations, were hardly sufficient to contain the complex circuit board-like pathways he painted. He soon found himself experimenting with the spaces beyond the canvas, first by painting on walls and then by exploring the whole of the 3-dimensional spaces he was exhibiting in.

“I decided I wanted to make my work inescapable and ever-present,” Songailo explains. “Instead of having to mentally project into the picture plane, visitors to the show would be inside the painting. There would be an experience for them to have and then leave.”

Digital Wasteland, 2014 – Photography by Emily Taylor

Digital Wasteland, 2014 – Photography by Emily Taylor

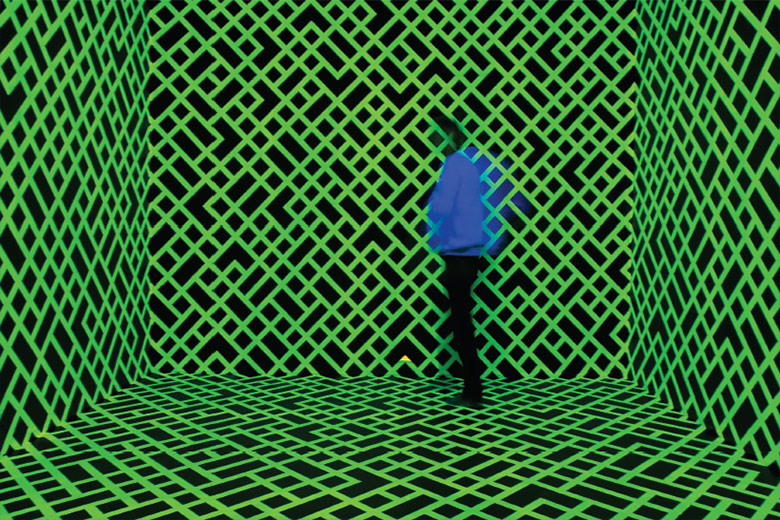

As Songailo creates, a number of concepts and miniature rules emerge, which serve as a guiding and linking thread throughout his work. One can find much of this wrapped up in his close relationship to music. Looking as far back as 2010, one can see that Songailo openly took a number of cues from electronic music through his Paintings About Techno series and his interdisciplinary exhibition, Media Centre, where blacklit neon walls of geometries engulfed anyone who entered it. Electronic music and sounds have always played a huge role in Songailo’s life, and it seems only natural that they would inform the sci-fi futurism of his work.

“I remember someone playing a hardcore techno tape at a party in high school from their car. It was the most alien and exotic thing I had ever heard,” recalls Songailo. “When my brother and I were growing up we would have to spend hours playing in our parents printing factory. I used to make up songs to the machines and sing them in my head. I attribute my love of electronic electronic music back to those days. The emptiness and coldness of electronic music is a feeling I try to impart into my work.”

Media Centre, 2010 – Photography by Sam Roberts

Media Centre, 2010 – Photography by Sam Roberts

Yellow Room, 2012 – Photography by Emily Taylor

Yellow Room, 2012 – Photography by Emily Taylor

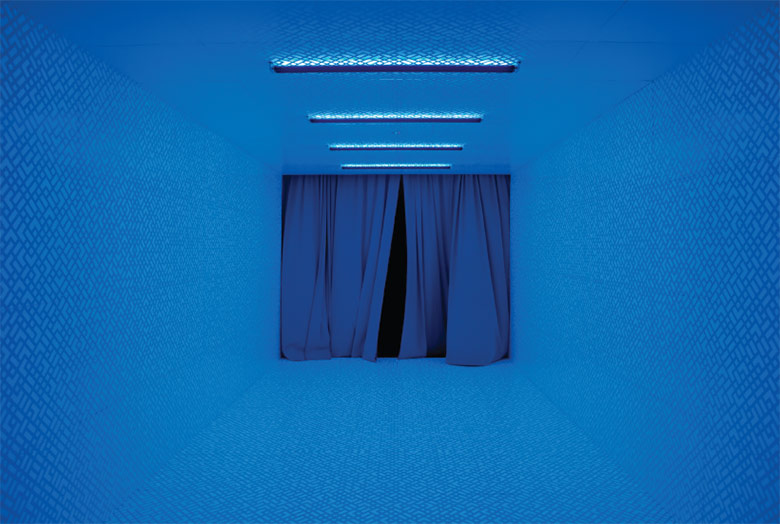

Opening, 2012 – Photography by Emily Taylor

Opening, 2012 – Photography by Emily Taylor

Electronic Inspirations Mixtape

“I have never been one of those people who holds on to the names of artists or musicians very well. Now that I am addicted to SoundCloud, the problem is worse. If I really like a tune I will play it over and over until I hate it,” says Songailo, who considers these tracks particularly inspiring.

Bah Samba ft. Fatback Band – “Let the Drum Speak”

Sepalcure – “The Warning”

ZOMBI – “Sapphire”

Flash And The Pan – “Midnight Man” (1985)

B.W.H – “Stop”

ZAZU – “Captain Starlight”

Todd Terje ft. Bryan Ferry – “Johnny and Mary”

Yet despite the emptiness and coldness found in much electronic music, there is also a bold, explorative human element to it which Songailo’s work also manages to capture. In a brilliant piece from May 2010, journalist Matt Huppatz describes beautifully the ways in which the work of Songailo connects with the colors and vibes one finds at underground electronic music parties, and a related spiritualism and ecstasy that comes from being wrapped up in the multisensory awe of it all.

“When I saw Paintings about Techno, a door opened into Sam’s work. It took on dimensions beyond the carefully constructed surface of colour and line. Sam’s paintings shifted from safe and contained and flat on the wall, to pulsating and rhythmic entities in my mind’s eye. They unfolded, expanding shards of light and colour radiating into my neck, my chest, my arms and legs. I was on a dance floor, enveloped in the brilliant white of strobe on smoke and radiant streams of colour from disco lights. Sonic waves radiated from speakers, reverberating through space, attuning everything and everyone to one vibrating, resonant unity. Paint became light, colour became sound, and pattern became temple. The fact is I knew these spaces; I’d been on these trips.”

– Matt Huppatz

By nature, visual art is often full of artist statements and explanations written for onlookers to better relate to an artist’s ideas – and that is why Songailo, who cares first and foremost about the general “feel” that his work imparts on visitors, sometimes finds music to be a much more soothing companion.

“Music makes sense to me much more than art,” he says. “It doesn’t make any claims to anything, it just is.”

Songailo’s gridded walls certainly impart a feel– but given their obvious connection to electronic music, one can’t help but wonder if there are correlations between the sounds he is inspired by and the distance between the lines he paints, or the colors he chooses. On an internalized level, it seems that Songailo indeed has systems in place for creating associations between the visual and the aural.

“There are algorithms I use when I make things and after a while, I get sick of them and feel like I want to do something else, but I also feel like I am in some way bound to look at what I have done before and create something that fits into the strange little journey I am on,” Songailo explains. “Change happens slowly. I have to remind myself that I am working on a long-term project.”

A confusion of perspective and frustration with scale seems to be a very natural side effect of working on projects to laborious, detailed, and time-consuming.

“When I am working for long periods of time, I get to a point where I think that what I am doing is ridiculous and stupid,” Songailo admits. “At that point, it’s time to go home and come back tomorrow… There is always a point in the process where I really hate the work and think it is stupid and also usually a point where I sit back at the end of the process and take in that intangible aspect of the work that makes me feel like it was worthwhile.”

Ω

Zen Garden, 2013

Zen Garden, 2013

Splendour Arts, 2013 – Photography by Emily Taylor

Splendour Arts, 2013 – Photography by Emily Taylor

New Sound, 2013 – Photography by Sam Roberts

New Sound, 2013 – Photography by Sam Roberts

Ω