The urge to mythologize such a person is strong, but Kalma’s nature defies sanctification with a radiantly mollifying humanity that courses through his work. His early albums such as Osmose and Open Like Flute are deep and meditative, with qualities that earn him a welcome place in the wider New Age canon. But unlike many of his peers from the ’70s and ’80s, who sought to explore the cosmic nature of the soul, Kalma’s music has always been a visceral affair that explores the intersection of body and spirit. His best pieces are timeless precisely because they are corporeal expressions of the right here and now. Much of his early work was improvised and the performances, while expertly played, are quite raw, as was their production quality. His loose approach lent those records an immediacy that mirrored the messy details of life on the spiritual path. There are no easy answers on his albums. No overhyped mysticism or guru worship. Just an artist and his tools, investigating the phenomenal expression of the void with an overarching sense of awe, wonder, and love toward everything this life has to offer.

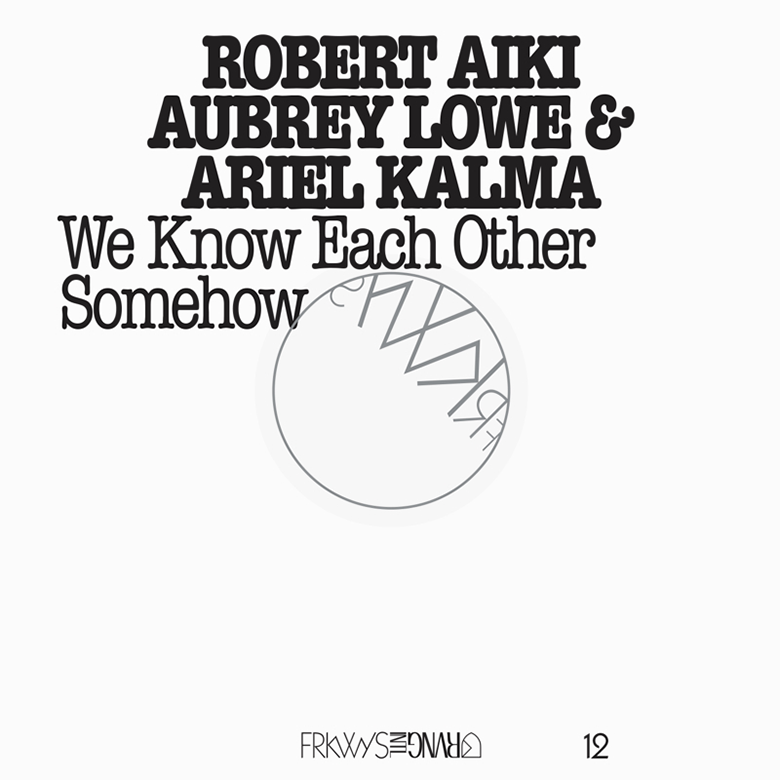

And the man is still at it today, releasing his own music and others’ through his label Music Mosaic. His most recent album is a collaboration with Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe of Lichens and Om fame, and it is entitled We Know Each Other Somehow. It’s a phenomenal recording by two artists known for their intense creative output, and who were apparently born to jam together. We Know Each Other Somehow is, in my estimation, one of the best entries in RVNG INTL’s ongoing FRKWYS collaboration series. It is also the vehicle for Kalma’s long overdue emergence on the international scene.

I had the opportunity to ask Kalma a few questions related to the record, and he was every bit as genuine and forthcoming as his work has made him out to be. I got the sense that while those of us enthralled with outsider ambient music have considered his newfound recognition and reissued catalog to be something of a blessing, he has taken it as an nice footnote to an ongoing adventure — which would have continued, even if no one else was paying attention. Kalma’s work has never been about acknowledgment. He is focused on the infinitely unfolding process.

Ariel Kalma

Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe

Robert Aiki Aubrey Lowe & Ariel Kalma – “Strange Dreams” Official Video

The compositions on We Know Each Other Somehow flow like highly considered improvisations.

Both Robert and I: we work with organized chaos, as we call it. We both came up with the same idea of organization and [living] of parts, which is the organizational part. Completely open. So yes, we had defined some structures, especially because I come from a lyrical [background] — [with] instruments like saxophones, and also I play with keyboards, which means also that there is some scales which I am interested in which explore moods coming from Indian music and coming from Western music, also. We express each other in moods and in tonalities — scales which are evoking some different feelings. One of them, for example, is the blues, which is in itself a tonality. [Kalma plays the flute and sings a melody.]

When we reach that note, which is very typically Western, it evokes a feeling. So choosing the scales was more my domain, and choosing the tonality and expressiveness of this. And then Robert added his precious modular synthesizer loops and sounds and different types of expression with electronic — that came hand in glove with one another, my contribution and his contribution. And that’s why you call it considered, because yes, we consider, what are we going to do? What do we want to express?

But there was still the improvisation part, which is like… for example, when we had that piece with the birds, we were practicing a piece and I heard the birds outside, and I said, “This is incredible; they are talking in the same key.”

So what provoked what, we don’t know, but we went for a walk, and I left the portable recorder on a tree trunk, and when we came back, we had birds recorded in the silence of the environment. We decided to tune that piece into the birds… after that, I played the saxophone, kind of improvising with the birds — going around the birds. So yes, it’s considered improvisation, maybe. It’s a good term, “considered improvisation.”

What was the writing and recording process for the album?

Well, we had one week, and we would come in the morning and say, “So, what do we do?”

I had some sketches of ideas which I thought would be a good… and Robert had some ideas about what he wanted to do with me, so that was easy. We covered several of my sketches.

Did you have any intention for it before you got started?

The intention was to make good music, and to explore what we could do together to the deepest… The rest we left to the muse.

How did you decide upon a sonic palette for the record?

It kind of grew by itself. Actually, by the limit of our limit, the palette developed its flavor by itself. It’s like, Robert is very good for voice, with his synthesizer, and I’m also good for voices in my way. Then he plays this modular synthesizer which makes samples and loops and all kinds of sounds, so that gives it a palette already. And me, with my limited keyboard-playing and my unlimited saxophone-playing — can I say that? –I feel very free on the saxophone, so I can go in many places… on the keyboard, I am restricted by my fingers, I think. But anyway, once I am in the trance, I don’t feel restricted anymore. So it’s just my mind who says I’m restricted.

Yesterday, I was recording a test with my new equipment and realized that, at one point, I had no idea what I was doing, but something was doing something very interesting. I think this is the trance that I wanted, and to create that with Robert in the studio was a challenge, and at the same time, it was easy, because we both come from improvisation…

Both of you produce music with distinctive meditative qualities. Do you have rituals for preparing yourselves to enter these kinds of zones? If so, did you share these procedures with each other or create any new rites?

It’s an interesting question. We did not have rituals. The rituals that came to us was to just do work and go into that zone of working. And out of this came the meditative feel that you capture in our recordings. I think both Robert and I have this inherent meditative state which we reach by doing our music. Music is the closest to silence. I really vibe with that. It’s like once we enter — [Kalma then pauses to speak to his cat and tell his cat to tell the interviewer hello through “meow”s.] — the meditative qualities in our music came by playing our music. It’s quieting. Just by doing those sounds, I go into a very quiet trance, and I can sometimes play strong — strong saxophone or keyboard phrases or sounds that break the silence… but it comes from inside. That’s all I can say.

So, no, we didn’t share procedures of any kind; we would just sit here looking for sounds or for ideas. It was kind of very natural. What we shared were some experiences of past meditations — like Robert was interested in my stay at Arica Institute in New York, and in France, also. We shared a lot of stories, actually, during that week.

Sunshine Soup Official Trailer

The film Sunshine Soup was a beautiful visual compliment to your record.

Oh, they were so good; [filmmakers Misha Hollenbach & Johann Rashid] were [such] beautiful people. Both were musicians, so they were quite sensitive to everything. It was like they were not there. They were here, but they were not there. They would record everything basically with one or two cameras at the same time — but it was very, very low-key, and both Robert and I were kind of oblivious to them. No, it was absolutely beautiful.

Your music which is extremely visually evocative for me. Does the process of creating or listening to music stimulate other senses for you?

When I play music, I go inside and I have all kinds of feelings and images, sensitivities, memories. It’s so interesting to go. Yesterday, I was playing that piece, and practicing that piece and, suddenly I realize I was making these gestures, as if I touched something almost painful, almost. Because I touched a note which was really, aw it was there, not there — sometimes I look outside and I’m inspired by the sky and the trees undulating in the wind. Does that answer your question?

There is something really disarming and beautiful about the promotional shots of you two hugging. How were these images captured?

There is something really disarming and beautiful about the promotional shots of you two hugging. How were these images captured?

Well, it was a really good hug. We didn’t really care who was around; we just had this wonderful hug, where we just connected with each other. I love hugs. I think hugs are a very deep connection with another human, so I love it when you say disarming, because if we could hug more people, yes, there would not be arms. There would just be arm. -S. I take you in my arm, I want to do no harm, and we will not use any arms. [Laughs.]

You like that poetry? Instant poetry? But it makes sense. Disarm. It has both the meaning of disarmament and peace. So yes, that hug was peace. So yes, maybe it was beautiful because of that. It evokes that peace that we could create by just loving more, and showing it, and sharing it.

Gosh, I go in another subject like this — that has something to do with the therapy groups that I’ve been doing for years. We see that so many times that, when there is tension, if we can go towards the other and just hold the other, there is disarmament, there is a let go. It takes a few moments which is why that hug, which is the promotional shot, is important — because we stayed for a while. It was not just a hello, bye-bye. It was the meaning of a deep hug, not an A-frame hug, which is very common in so many places.

You have both covered a fairly large amount of sonic territory in your solo careers and collaborations, but We Know Each Other Somehow is a fairly seamless combination of certain aspects and eras of your individual works.

The sonic areas are a reflection of the collaborations that I have had with people — or may I say, with myself, because sometimes I have a feeling that there is two sides of myself, which is… one is the guy who lives this daily life, and the other one is this guy who has the ability to tap into music and transforms emotions of the second guy into music. Of course, once I play music, the two guys are reconciled, and it is only one person. From the outside, it feels like, “Who is this guy who can compose music? Who is this guy who can live the life mundane? — let’s put it like that.” So that’s a collaboration. Collaborations with myself, or collaborations with somebody else.

The sonic palettes, which you were talking about before: they were different because of the different environments and the different spaces, maybe, inner space, where we were at that time. So yes. But there is a common thread. There is the continuum which is, for me, for example — those scales, which I was talking about before –which evoke more sensitivities to certain scales. So maybe that’s what defines me as a person.

Of course, there are many ways of looking at who we are in terms of persons and composers. Certain aspects and areas of our individual works. For me, my individual works are those emotions via the music. The exploring, the playing, and the transmission… I transmit what I perceive, and then somebody, the listener, receives that transmission. It feels a bit preposterous to say that, but still, it is. I capture. I’m an antenna. I’m an area. I receive, I capture, I translate, I play, I record — then it’s the listener.

So, did I transmit something interesting? Did I transmit something sensitive? Am I carrying my emotions with me? Am I transmitting those emotions? Am I moving? But I’m getting further away from your question.

How do you feel this album fits into or contribute to your discographies?

I don’t consider my career as a discography. What I mean is that, I’m doing music one after another to express who I am right now and what I feel right now, and I’m not looking back at my life with a discography in mind. So yes, I have all those albums, but I also have many other albums which have never been born which cover different styles, different genres, which maybe will happen now that I have time in my life to do my archives.

At the same time, I’ve gotten new equipment, so I’ve got new potential possibilities which I’m exploring also. I feel my contribution with Robert is perfect for who we are right now. I hope I contribute something to Robert’s life and he contributes something to my life, because he’s of a different generation and he’s interested in what I’m doing, what I’ve been doing, and what I’m doing now. So it’s perfect.

In the last few years, I’ve had the opportunity to see classic New Age artists like Laraaji and IASOS play and give talks and guided meditations. In my limited experience, it seems that new generations of fans are more willing to embrace those artists’ music than the cultural and spiritual practices that are generally associated with that scene in its heyday.

I’m so happy that Laraaji and IASOS have a voice. I think the new generation is more interested in the music itself without the so-called spiritual practices which were associated with this in the past. It is difficult to associate spiritual practice and music. The music talks by itself. It’s easier for people to connect with music and feel good about music, like I feel relaxed, it took me someplace, I went on a journey. That is easy for people to let go and associate some music with different feelings inside.

Now, the spiritual practices and cultural practices: that’s more difficult for people to reach, to make the commitment to relax more, meditate… that’s a big commitment. Also, frankly, those people were avant-garde. There was no music like that. And their limited success showed that it was avant-garde. It’s like my music… it’s difficult to be an avant-garde person and be recognized at the same time, because who would be avant? The frontline of research and development goes through those spiritual and cultural practices, but it’s only by the reflection of the music that people outside those practices can connect. So via the music, you connect to the spiritual. So yes, Laraaji and IASOS are doing the guided meditations and talks. That’s fantastic. Because they have been recognized as offering something that has a spiritual or meditative value, relaxing value. So great, wonderful.

As an example, I want to tell you one of the big experience in my life is when I came to a concert in New York, by Sri Chinmoy. I had heard about Sri Chinmoy before, and that he was a meditator and a guru, that he played this beautiful…instrument. So I was curious to go and see that. It absolutely stunned me what the radiance Sri Chinmoy was pouring out through his music. For me, it was such a beautiful discovery of, no matter who he is in his spirituality and his practice, the way he presented his music was completely open and completely transparent, and at the same time, connecting with the public, as if he was connected one-by-one to every member of the public. That was very, very significant for me to experience. And that’s why I mention him on the cover of [my] album… as one of my mentors, although I’ve never met him; I’ve never talked to him. For me, he was absolutely important in my life, you know, and I’m so glad that I met him, because he gave me the opportunity to experience spirituality in action.

Have you noticed a shift in how people respond to your music over the years?

Yes, yes. When I started making music, there was really very few people who responded to my music, because there was no genre like that. Can you imagine, in 1975, when I came out with my album, Le Temps Des Moissons, in France, I went to record shops. First, I went to record company with my tapes, and they were saying, “What is this?” and then I produced my album myself, and I went to shops so that they could sell it. I had the product, but shops would say, “We have no box for it. It’s not jazz; it’s not classical; it’s not rock. So… what else?” So in that sense, my followers were very little. So then this guy put my record at night, late at night, for a long program on French cultural radio, and there was a great response. But still, it was really limited, and at that time, who was interested?

There was Osmose, and Osmose had a small response also. It was with a record company, but it had such a small response; I never knew how many they had sold, because that record company never communicated after we published the album. There was very little reaction to my music.

Then I decided music would not be my career, because at that time, I thought life was my career, so I did all kinds of other things that took me to different realms of consciousness. I was always doing music because music is part of me, and I know how to record. I always did music. In the group therapy I was collating and sometimes leading, music was an important part. But still, it was a very limited reaction, interaction, with the public, in general.

It’s only a few years ago that I realized, “Oh wow, my first albums are selling for quite expensive and people are interested…” My first vinyl LPs were selling for expensive, and people were interested, and I produced more recent albums and put it on the net and sold some and developed a following. But it’s not until recently that I discovered, actually, there is a whole bunch of people who like my music, and all those years, my music has gone through scores of people, which is wonderful. I’m so happy about that.

So yes, I was avant-garde forty years ago, and now I’m not avant-garde anymore. I’m part of the circle of people who love Terry Riley, who love Tangerine Dream, who love all kinds of people, IASOS and Laraaji. And maybe more. I don’t know who is really my public out there.

And then I’m happy to talk via your interview to the people who are interested in my music to just tell them I still have some avant-garde things to produce before I leave this planet.

Do you feel like something has been lost or has it been given a new life in a different context [with the resurgence of the New Age movement]?

Well, I think people are more sensitive now, and also the radios are opening up; there is the internet. Not the radios, because the radio’s always been difficult for me, for example, with my long pieces of unconventional jazz… who would play my music? But now, the internet is here. The internet opens tremendous possibilities — so I don’t think something has been lost. I think something has been gained. It’s a new life in a different context. It’s called the internet. The age of instant communication, global communication, where anybody who has a voice can express and be heard by somebody. Not necessarily through the channels of record labels and syndicated radio shows which have no time for us. It’s not mainstream. So I don’t think anything has been lost. On the contrary, look at all those pieces that were on this double LP, Evolutionary Music, produced by RVNG; that might have been lost, although I was working on my archives. But to be presented like that by this brilliant company: it’s beautiful… the globalization of communication has opened the possibilities. Infinite possibilities.

How do you feel about the recent reassessments of early ambient and New Age records and careers?

I feel good. I feel it’s about time the general public realizes that there are choices other than Top 40’s or jazz or… that there are so many different styles of expressing music, it opens the ears of everybody. That’s one part.

The other part is the connection with nature and a simpler life in comparison to the hectic busy environment in which modern daily life puts us through. I think it’s very important that I can go and play and bring my music, along with nature sounds and birds and things like that, and bring that quietness or inspiration — because birds inspire me; they have their song, they have their callings, they have their voices, they are tuned in a different way — and if we can tune into this, we become part of nature. Why have we lost that? I think that this ambient and New Age records… that’s what they wanted to do. To reconnect us with the way of life which is not so hectic.

Now, about the careers of early ambient and New Age careers… I’m not sure about that, because I did not follow careers. I was busy with my own life.

But I’m very happy that people who devoted their careers to this type of music are recognized, and not only Brian Eno, so that lesser-known people become more known. There are so many absolutely gorgeous compositions out there, which need to be rediscovered, because it’s eternal. Music for Airports: there is nothing like this, although it’s easy to make, but he was the first one to make it. It’s just a state of mind. And I think the state of mind is coming to the front for many people now, because it’s important. We need to reconnect with nature; we need to reconnect with quietness. In the future — not so long — we will consider a square meter of nature with the same price as a master painting, because nature will have disappeared from our life, and therefore we will recognize a square meter of nature. And I’m very fortunate to live in nature after having been in urban environments for so long.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

I have really enjoyed working with Robert, because he was so knowledgeable about so many details — about technology, about developments, about synthesizers, about people. I mean, we had conversations where, when he was here to record the album, he was very animated. I was casually mentioning a name of somebody who I had met or who had a conversation, and Robert was saying, “Oh wow, tell me more about that; I know him from this, and I heard him from that” — so it was really a wonderful immersion into a friendship which was developing and coming from a place of knowing where I came from. And Robert knew where I came from, because he knew his classics, so to speak. He knew the people; he knew the groups that I was with. Except some in France, of course — he did not know that. But that was a particularly memorable moment.

Another one comes to me now — and you saw in Sunshine Soup DVD — at one point we went to… a little town near us. And of course, [directors] Misha [Hollenbach] and Joey [Rashid] were with us, because they were filming everything, so we met a few friends, and people were filming that, and then we went to a special coffee shop which has lots of memorabilia. So we went for a drink, but I struck conversation with a very colorful persona who was sitting on the bench, and I instantly saw that this was a trip guy. That this guy had stories. So Misha and Joey were inside the coffee shop, but I called them and said, “Come, come, and please film everything, because it’s going to be very interesting.”

And then it went on, and you probably saw the movie — that guy who deliriously talks about how he was bitten by a snake and walked around, I don’t know, 20 kilometers before he got rescued… that was a very memorable event for me.

www.igetrvng.com

Ω