—

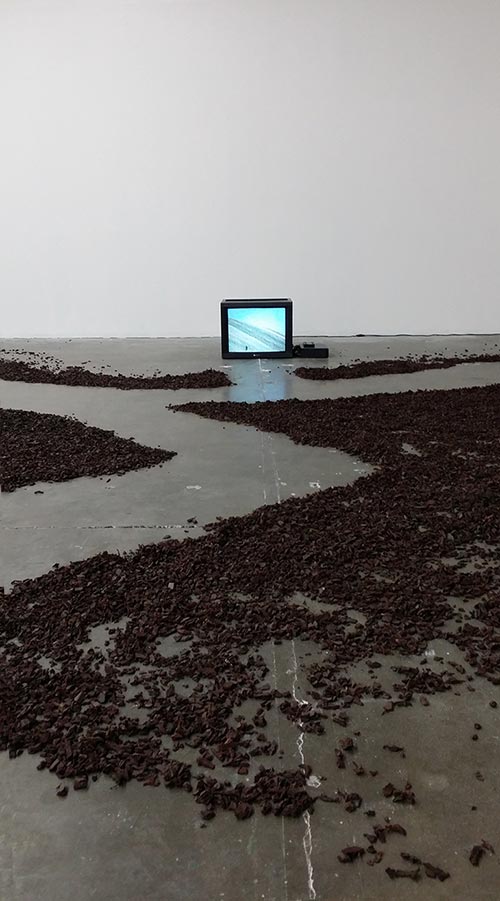

Video by Keith Skretch / Structure by Shannon Scrofano

This combination of elements is strange, popping visually but feeling a bit dry, like a mix of Japanese traditionalism with Scandinavian modernity. Every time artists and performers Jennie Liu and Andrew Gilbert appear on-screen, they offer little in the way of complex facial expressions or non-mechanical movements, and it is hard to discern whether the text accompanying their movements is meant to be humorous or not. These videos serve as an introductory precursor to HOUSE MUSIC — the performance piece Liu and Gilbert developed over the course of a month-long residency at The Mistake Room — and given their somewhat head-scratching nature, one can’t help but wonder just what mood the performance itself might embody. Will it, too, feel a bit rigid and antiseptic?

Definitely not, one soon concludes. Donning a striking, custom-crafted workman’s jumpsuit, Gilbert is all smiles when he appears — and like a long-time friend, he invites guests to enter his “home”, gingerly taking their hands as he assists them in crossing through the circular entranceway. On the other side, they are greeted warmly by Liu, who happens to be wearing an even better jumpsuit. She suggests that they take a moment to admire the flowers — which she and Gilbert replace daily, as a part of a set ritual they’ve developed for the residency — and then to choose a seat, each of which has a pair of headphones lying upon a pillow of recycled industrial felt.

Steve “Silk” Hurley — “Jack Your Body

What transpires over the course of the next 45 minutes is varied, adept, and presented intimately through playful sound design. The two immediately launch into a groovy cover of Steve “Silk” Hurley’s classic Chicago house track, “Jack Your Body” — and it may very well have been taken as an original work if Liu and Gilbert had not given proper credit. Instead, they use it as a jump-off point for Liu to poetically unleash a number of rhetorical questions.

Who is Jack? — she inquires in her perfectly sultry late-night radio DJ voice — and what does it mean to jack one’s body, within the context of a tangible space, or an intangible space, as within a song?

Thus begins the loose cycle of action and reflection that persists throughout HOUSE MUSIC, which boasts a title that adorably encompasses a good portion of what the performance is. But not only. The use of sociocultural references as the basis for movement and direct dialogue is not limited here to house music, as in the case of “Jack Your Body”, but extends to many things, including American roots music and contemporary dance.

John Fahey — “Guitar Lamento”

Switching from an electronic sampler to a guitar, Gilbert soon asks if anyone has heard of the roots musician John Fahey. His inquiry falls largely to silence, and he proceeds to enact a memory. As a younger man, he had just discovered Fahey’s music and, blown away, was incredibly excited to show a musically like-minded friend his findings. To Gilbert’s surprise, his friend was skeptical and unimpressed.

“You can hear his mistakes,” the friend had responded, and Gilbert could only mutter, “I can’t even begin to explain this to you.”

Years later, Gilbert decided to show Fahey’s music to his father. Like the skeptical friend, his father wasn’t a fan — yet the older man’s skilled ears heard something more: that Fahey gained access to areas on the guitar that were completely invisible to the less skilled. For Gilbert, this illustrated that Fahey was not merely playing his creations, but that his mastery actively allowed him to adlib and build upon his creations while he was playing them.

Such a statement may seem redundant or contradictory, but in fact could read rather Buddhist. What Liu and Gilbert work towards throughout HOUSE MUSIC is the notion that “practice” is the flawed but necessary step to attaining a mastery so complete that the brain no longer needs to try. Such mastery is akin to creating a vacuum within a structure — said vacuum being the state of nothingness wherein complete freedom can be found.

As pop sociologist Malcolm Gladwell posited in his 2008 book, Outliers, putting in time is vital to success in any craft, and Liu and Gilbert seem well-aware of this concept. With almost twenty performances over the course of seven days, HOUSE MUSIC is an ongoing work-in-practice, and everything about it is richly layered and iterative. The “house” and the space within its walls are the physical manifestation of creating a vacuum inside a structure. Its design is also a cover song of sorts — a recreation of a Japanese tea house, set in nature, which the artists visit weekly.

Trisha Brown – Accumulation with Talking plus Water Motor

In her equivalent to Gilbert’s John Fahey cover, Liu offers context on postmodern choreographer and dancer Trisha Brown, who, amongst other things, is known for deconstructing dance to basic building blocks, then reintroducing elements through an additive process. In her highly complex solo piece, Accumulation with Talking plus Water Motor, Brown complicates an existing dance by introducing an additional dance — thus alternating the final movements back-and-forth between the two — and adds an element of mental prowess by reciting a lengthy verbal narrative.

“While I was making this dance, I went on a holiday and continued to practice standing on a dune, facing the sea,” Brown slowly reveals as she moves. “One day, a ranger appeared on my right. And no matter what he did, he could not get his horse to pass me.”

Liu references this dialogue by shifting it slightly. “One day, a ranger appeared on her right,” she says of Brown’s piece, “and no matter what he did, he could not get his horse to pass her.”

“One day, a ranger appeared on her right, and no matter what he did, he could not get his horse to pass her,” she then repeats again.

Stacy Dawson Stearns – Red Doll Buck Dance

On a basic auditory level, simply repeating this line would have been plenty satisfying. But Liu eventually takes it much further, into mind-blowingly multi-layered realms. She herself introduces two dances. One, made by choreographer friend Adam Linder, is full of frozen pauses and repeating phrases, which vary at intervals freely dictated by Gilbert. The other is a buckdance — a type of step dance done primarily by individuals in the Southern Appalachians — and this particular one, entitled Red Doll Buck Dance, serves as a rite-of-passage, written for a homosexual boy who committed suicide because he was bullied.

“Stacy Dawson Stearns performs it beautifully,” Liu says humbly before beginning. “I’m practicing.”

Yet one would think, from how Liu seems to move with complete confidence and abandon, that she, too, had already gone beyond the point of “practice”.

The culmination of HOUSE MUSIC comes when Liu uses Brown’s Accumulation with Talking… as the foundational structure, then weaves previously deconstructed elements together into a final piece. Liu switches back and forth between the two wildly different dances by Linder and Stearns — using the more relaxed nature of the Linder’s piece as the main narrative vehicle — and as she recalls childhood memories of a rather psychedelic nature, Gilbert repeats her words in near succession.

It’s a lot of data, and it all swirls together rapidly. The desired effect, presumably, is that visitors to the house of Liu and Gilbert will be unable to look away, they themselves like the stunned park ranger on the dune, facing the sea, unable to get their horse to pass.

Ω