Photo courtesy of PO Box Collective in Chicago

– Mary Zerkel and Salome Chasnoff, PO Box Collective, Chicago, IL

Community Relief from COVID-19

In Chicago, the 19-member PO Box Collective builds community through radical art making and mutual aid, with dynamic programming that includes everything from skill shares and writing workshops to artist salons and clothing swaps. Housed in a former post office in the city’s Roger Park neighborhood, PO Box Collective hosts free events that are driven by sliding-scale member dues and donations; they also offer their space to local activist groups and are a regular outpost for Food Not Bombs, who rescue unsold groceries and redistribute them.

“The reason that we are drawn to both art and social justice is that we want to remake the world, and DIY spaces offer possibilities for those who don’t want to be caught up within institutional structures and constraints, more direct access to collaboration and community building, and room to move for those without a lot of money,” explains PO Box Collective members Mary Zerkel and Salome Chasnoff.

PO Box Collective purposely strives to operate outside of capitalism to the extent that such is possible — and this includes an avoidance of 501c3 nonprofit status, which has rendered them ineligible for many of the COVID-19 relief funds available for formalized arts organizations.

“We turn to each other and the larger community for our wants and needs. This makes us all stronger,” explain Zerkel and Chasnoff. “The precarity that was already being experienced by many of our community members — from the carceral state, religious and political persecution, living with economic and health precarity and no social safety net — has intensified. We need to be able to rely on each other and build hyper-local systems of support to survive and thrive.”

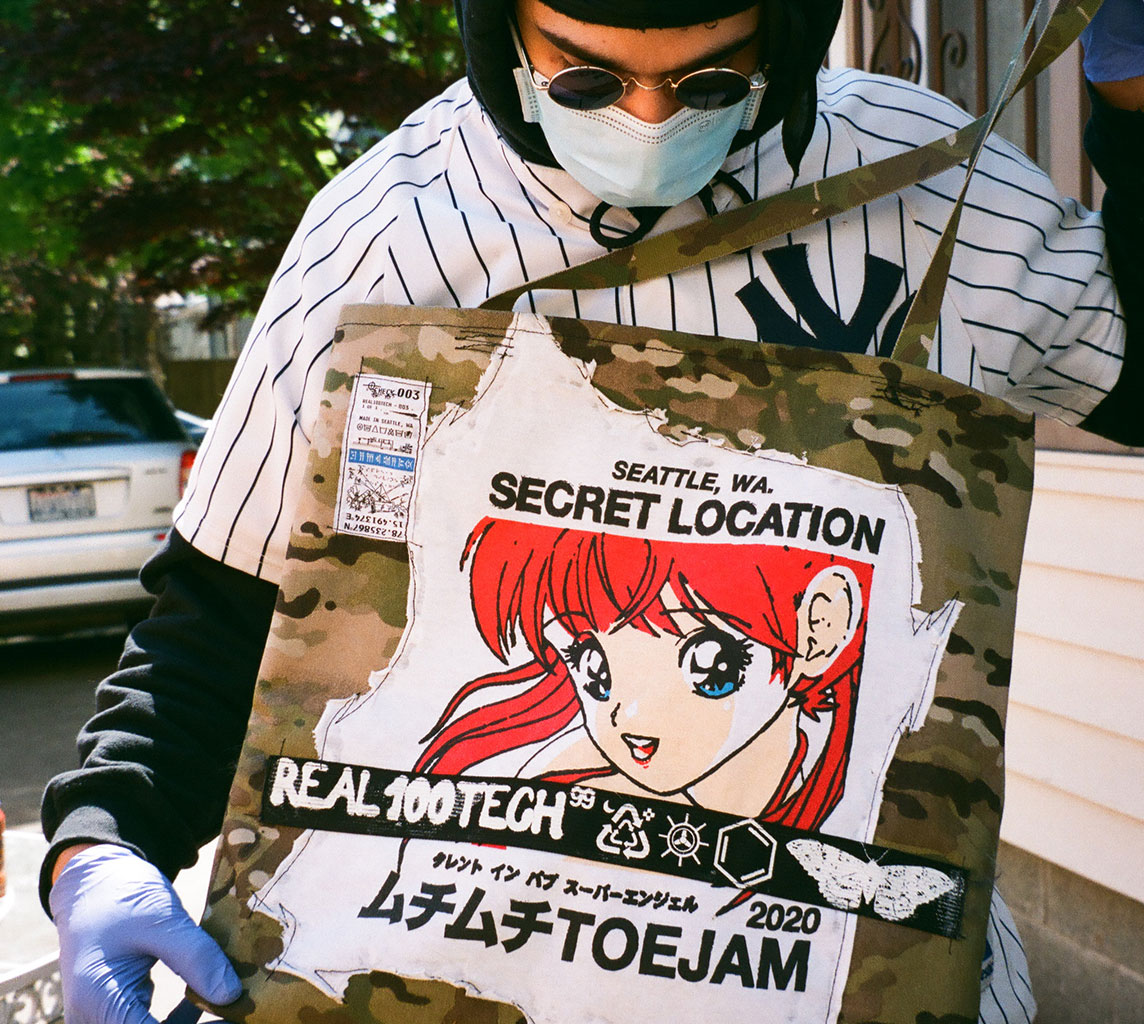

Livestream video and photo courtesy of Toe Jam

Western Washington collective Toe Jam also relies on a hyper-local system of support. Prior to the pandemic, they built up a fiery reputation of hosting monthly warehouse rap shows, which provided “a safe space for creatives to showcase their work, network with other motivated artists.” Like many, the pandemic prompted them to focus on livestreaming high-quality DJ sets with immersive visuals, but they too had a problem receiving COVID-19 artist relief funds, despite applying for them.

“To tell you the truth, we are used to that though,” Toe Jam note. “The powers that be tend to shy away from us.”

For Toe Jam and many like them, such systemic equalities were present well before the pandemic. Looking back on live show booking standards, they explain, “There’s no reason why I should have to pay $5,000+ to rent a space for the night. Artist funds, music festivals, art walks, pop ups, outreach programs, art galleries, venues — everybody in charge needs to do their homework and be even more inclusive because there are entire subgroups of artists that feel left out prior to the pandemic and even moreso now.”

Momentum Better Generated Together

A nationally-recognized all-ages venue based in Seattle, The Vera Project began in 2001, when limitations under a Seattle-specific Teen Dance Ordinance prevented young folx from participating in late night music events.

“It took a long-term, coordinated grassroots organizing campaign, largely empowered by the DIY scene, to overturn the ordinance and reestablish a youth-driven music community,” Executive Director Ricky Graboski describes. “Vera was one of the end results of that effort, bringing a gathering space to those outcast young people and artists, while offering the city a safer alternative to underground shows.”

Though The Vera Project is now a nonprofit organization with an annual operating budget of close to a million dollars, they try to honor their history and leverage their status accordingly. In the early months of COVID-19 pandemic closures, they helped develop a Washington DIY coalition and “Live From Our Living Rooms,” a livestreamed telethon-style series of music, art, workshops, and speakers, where 100% of proceeds went towards those disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. They raised over $100k towards community relief efforts — much of which went towards venues and galleries which typically do not qualify for formal institutional support.

Photo courtesy of Redfishbowl

Across the country, Pittsburgh’s Redfishbowl took on a similar role. The 5,000-square-foot, 24-hour artist co-working space, gallery, and performance center suspended their studio operations and large-scale festivals shortly after the pandemic began, but sent a letter to potential partners in the area, inviting them to collaborate on virtual events designed to “combat the economic effects the COVID-19 outbreak has had on our small business community.” The model took advantage of social media and the collective power of shared audiences, generating momentum via Instagram Live, Facebook, and Gofundme to present auctions, raffles, and events; proceeds were then split among participating organizations.

“When it comes down to it, we are all we got,” explains Redfishbowl founder Chris Boles, “so banding together and taking action is what we did, and that’s what we’re used to doing.”

Following the death of George Floyd, Redfishbowl, like so many others, shifted from fundraising for their own survival to supporting the Black Lives Matter movement. They launched a “Say Her Name” campaign to benefit Trans Youniting, which featured hand-spraypainted t-shirts of Breonna Taylor by artist Trenita Finney; at Civil Saturday, a weekly protest hosted by Black Young and Educated, they also helped create a 4-foot “Black Lives Matter” banner and subsequently sold prints to raise money for activist groups.

Similarly, The Vera Project’s youth-led membership — which plays a central role in all of their decision-making processes — unanimously voted to double-down on their grassroots organizing efforts in support of the BLM movement.

“We raised a bunch of money for Black-led community spaces, ran sound for protests, produced issue-focused livestreams, registered voters, facilitated youth-driven lobbying and campaign efforts, and even partnered with major BLM coalitions to screenprint and distribute anti-racist propaganda…” says Graboski. “I hope something actually comes out of getting the terms ‘mutual aid’ and ‘anti-racist organizing’ into the zeitgeist, but it won’t happen without a fight.”

Racial Reckoning Gets Real

Across the country, 2020’s racial reckonings forced many to look inwards at their own mission statements and power structures. One such group was Seattle’s TUF Collective, who were focused on “uplifting marginalizing folks including people of color, women, queer, trans, and gender nonconforming identities.” TUF did not occupy a physical space; instead, they hosted live events throughout the city, including the all-night party TUFFEST ‘Til Dawn and TUFFEST, an interdisciplinary festival with music, art, speakers, and workshops.

In mid-2020, after about five years of existence, TUF was dissolved by its Black and Indigenous members. One of these members was Liv Klutse, aka livwutang, who notes that TUF had become a “catch-all” collective for any artists who were not cis-white-men.

“Coupled with a non-hierarchical structure and an overwhelming white majority, it became difficult to maintain regular communication and reach consensus,” Klutse explains. “Within the realm of marginalized identities in TUF, there were a vast range of lived experiences — which is a good thing! But I think that, structurally, a greater specificity and clearer shared values would have encouraged better alignment with its mission.”

These Black and Indigenous members of TUF formed a diverse constituency, with varying experiences, feelings, and levels of involvement. Still, they collectively drafted and released a public statement, in part stating:

“TUF has grown to comprise a 70+ person membership with a white majority and without a racial demographic makeup reflective of those we sought to center, or a functioning structure and ethic of anti-racism in place. Consequently, TUF has not supported its current mission statement through structural and informal anti-Blackness, racism, and complacency. Although we believe that TUF has been an important entity in diversifying our local music scene, we need to hold space for new collectives to emerge that exceed where TUF fell short and that specifically address anti-Blackness in music, art, and media industries.”

“I have faith that despite the dearth of resources for BIPOC-led and centered DIY arts spaces in Seattle, new Black and Indigenous-led creative initiatives have emerged and will continue to. Not just in the void of TUF, but in addition to all the expanses TUF could ultimately not fill,” says Klutse. “Dr. Bayo Akomolafe once said that, ‘Descent and demise are shockingly generative spaces,’ and I think the dissolution of TUF is an excellent example of one such undoing [and] becoming.”

BABE HOUSE Founder Sarah Raymore, aka DJ Applejuice

DIY’s Future in QT/BIPOC

Two Black-led groups that help fill the TUF void include Housepartysea and BABE HOUSE, which have both hosted eclectic DJ sets and livestreams during the pandemic — at times in partnership with one another. BABE HOUSE was established in Seattle in December 2018 “as a collective of like-minded QTBIPOC artists that recognize the necessity of reclaiming house music histories and the importance of dancing with each other and ourselves as acts of resistance.”

“I definitely lost a lot of people in the process of trying to fulfill my mission to help with the QTBIPOC solidarity movement because the path work wasn’t aligning anymore for what my mission is and how I have grown a different direction than a lot of people I’ve known here for a while,” explains its founder Sarah Raymore, aka DJ Applejuice.

Raymore moved back to her home city of Detroit in 2019, and BABE HOUSE is now focused on being a national solidarity network for QTBIPOC, with an invitation for like-minded multimedia artists across the country to join their movement. Housepartysea, conversely, remains in Seattle, where it began as a weekly dance night.

“For Housepartysea, we try to represent the underground culture and present it to the masses in a digestible way to later lead them to the real rawness of it all,” says Arel Watson, Founder, Creative Director, and DJ at Housepartysea. “In that alone, I feel like the underground DIY culture is a political movement in itself due to the history of example to house, techno, and punk. It’s Black, it’s powerful, and it all arose during the most intense times in America.”

“We try to emulate that energy by creating a space that embarks culture learnings and the changes we want to see in Seattle,” Watson continues. “Best way to describe it is by doing it, not just saying what we are doing. Actions speak louder than words.”

At times, Watson is saddened by fewer DIY events, less artist support, and the departure of musicians from Seattle, but continues to push on, despite wondering occasionally if he himself might leave.

“But I also feel like I would be just adding to the problem if I did that, because who else is gonna step up and try to invest into their community?” he inquires. “So I’m investing my energy to try to create a space that creates opportunities for artists, people to hang, people to meet people like them, people to meet people that aren’t like them but are similar at the core, people that dance, people that want to learn, experience something.”

Photos courtesy of Housepartysea and Founder Arel Watson in Seattle

Opportunity in a Post-Pandemic Era

From coast to coast, media coverage about DIY spaces and organizations has historically come only when they are under threat or worse: long gone.

“Something that unites many of the DIY spaces I am familiar with is a constant struggle for financial stability,” explains JoJo Sacks, Coordinator of the Civic Media Center in Gainesville, Florida, which is a dynamic organizing space that offers a public-access library, workshops, radio station, and music shows. “I think the nature of the [Civic Media Center] as being a space that serves a lot of different uses and needs makes its sustainability a challenge — but this also is a benefit, as many different people want to see the space continue to thrive.”

“We exist at the overlap of artists, musicians, creatives, organizers, radicals, leftists, political thinkers in general, students, and liberals, as well as folks needing places to assemble for meetings and events,” Sacks continues. “Without this combination, I don’t know if we could make it through this time.”

While major venues and a certain echelon of music coalitions have garnered write-ups in major publications or spent the majority of the pandemic advocating for their own spaces, the question remains: who is looking out for the DIY community? As usual, it seems to be themselves and the communities that they serve.

“We exist as countercultural spaces, safer spaces, artistic spaces, and where people seeking community can get together socially. It is with this basis that people can organize together to create a future that builds up community in order to tear down the oppressive structures that make up the current world,” Sachs says. “When our city repeatedly does things to harm marginalized folx, we will host actions and bring people together to support one another. When people need a place to be, we have our doors open when the businesses, nonprofits, and government offices nearby close theirs. When given the literal space to be creative, to think independently, to learn real history, make zines, play instruments, people are able to flourish and grow in ways that show how important DIY spaces are.”

Photos courtesy of Civic Media Center in Gainesville

Links & Resources

All of these organizations and groups could use your financial support to thrive. Please consider making a donation today!

Collectives

- BABE HOUSE (Seattle / Detroit)

- Housepartysea (Seattle)

- PO Box Collective (Chicago)

- Toe Jam (Seattle)

- TUF Collective (Seattle)

Organizations

- Civic Media Center (Gainesville)

- Redfishbowl (Pittsburgh)

- The Vera Project (Seattle)

Resources

- Do DIY: DIY Resource & Organizer List (National / International)

- Safer DIY Spaces (Oakland)

- A United Cultural Front, Part 1: Models of Space Preservation & Creation from Oakland & Seattle via REDEFINE (2018 Article)

Ω

[…] exciting amount of zines produced from the drawing desks of artists quarantined at home, as well as DIY art spaces popping up to create community. So, in the true spirit of zinemaking’s DIY origins, I’m excited […]