Since the Dot-Com Boom of the 1990s, San Francisco, California, has left its hippie and counterculture roots behind to become the poster child for the affordability crisis. With that has come the slow exodus of its creative class, who, priced out, have been forced to seek cheaper alternatives.

At one time called the “Detroit of the West” due to its auto and war-related manufacturing, Oakland is one of the few neighboring Bay Area cities that has been able to maintain a vibrant community of artists and changemakers. Up until relatively recently, the port city has been blessed with a fair number of empty land parcels, which have insulated its population from more immediate effects of displacement, even despite new developments.

In recent months, however, high-visibility events have galvanized community support and called attention to changing dynamics within the city. These include efforts to raze the Afrikatown Community Garden, which had been revitalized by the radical community center, Qilombo, as well as the eviction of Auntie Francis, a former Black Panther who has fed the homeless every week since 2000. Especially inextricable is 2016’s Ghost Ship incident, which took 35 lives during a house party in an illegal live-work space. The tragedy sparked a national witch hunt, and city officials went to great lengths to enforce building code violations in DIY spaces – under the guise of safety, but generally without an understanding of the marginalized communities they were evicting.

ARTICLE BY VIVIAN HUA & ILLUSTRATION BY TESSA HULLS

Luckily, the residents of Oakland have never been ones to lie down. They concoct imaginative solutions to curtail displacement, instead – with solutions that tend to focus on resistance and preservation, while simultaneously uplifting its grassroots organizations.

800 miles north lies Seattle, one of the fastest growing cities in the country. Recognizing that development has already done notable damage to its local creative community, city officials are scrambling for solutions to build and preserve cultural space.

“Everybody feels like they’re way behind in this game,” says Matthew Richter, the Cultural Space Liaison for Seattle’s Office of Arts and Culture (ARTS). “The thing that ties us all together – the people working on this issue – is nobody got in there to invest and start making rules before the market got too hot to touch. Now we’re all trying to impact these markets that are running away from us.”

Although the efforts in both cities form only a tiny fraction of the overall picture, they offer a roadmap to how an entire community – from artists to city leaders, and everyone in-between – might work together to make long-term investments in art and culture. Furthermore, they serve to inspire cities that have not yet reached their saturation points to visualize the future and put protections in place before it feels too late.

Table of Contents

- Crowdfunding a Safe Space

- Stabilizing Art Space Globally

- Investing in the Long Game

- Uplifting Communities of Color

- Activating Self-Started Solutions

- Influencing Policy from the Ground Up

- Leveraging City Resources

- Stirring the Public Imagination

Please note that this article is the first in a REDEFINE magazine series on Cultural Space Preservation. On Thursday, August 9th, 2018, we will also be hosting a community forum at Northwest Film Forum in Seattle, to have an open discussion about these issues.

We are in the process of creating a public-facing wiki at makingspace.wiki, where anyone will be able to contribute their models and documents about cultural space creation and preservation.

This publication is run on a volunteer basis. Please consider supporting our Patreon.

Members of the Liberated 23rd Community Building, after their successful crowdfunding campaign. (Credit: Northern California Community Loan Fund)

Crowdfunding a Safe Space

Self-identifying as one of the last QTPOC (Queer Trans People of Color) spaces in Oakland, the Liberated 23rd Community Building is located in an industrial zone of East Oakland that would not stereotypically be considered “desirable.” Tucked away near a freeway underpass, the 100-year-plus building sits kitty-corner from The Village, a homeless encampment with a complex relationship to the city, and across the street from EastSide Arts Alliance, a rich community hub for workshops, performances, and affordable housing.

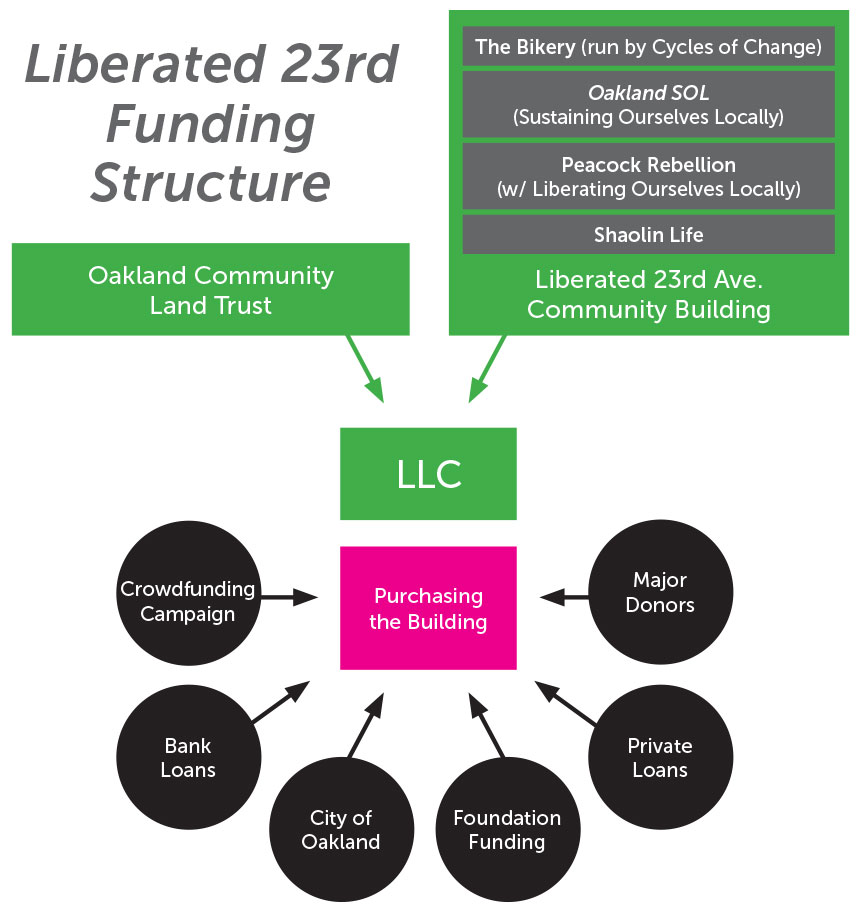

Liberated 23rd combines eight low-income residential units with four ground-floor commercial spaces, which serve as home to Sustaining Ourselves Locally (SOL), a food justice co-op; the Bikery, a community bike shop run by Cycles of Change; Peacock Rebellion, an institute that hosts a makerspace and trains storytellers; and Shaolin Life, a martial arts studio. Every organization is committed to serving the neighborhood and people of color, though some focus exclusively on the QTPOC community. Together with The Village and EastSide Arts Alliance, they hold down a strong cultural corner which plays a vital role in supporting some of Oakland’s most disenfranchised populations.

It was in late 2017, after a successful YouCaring crowdfunding campaign, that #Liberate23rdAve became the “Liberated” 23rd Community Building.

“The landlord [Ming Cheung] was our friend’s mom, and their family is a multigenerational family of housing justice warriors,” says Devi Peacock, the Founder and Executive Director of Peacock Rebellion, which, amongst other things, trains QTPOC activists, comedians, and storytellers to shape their own narratives. “She had bought the building to preserve it and convinced the previous owner to sell it so it could stay in the community. But after Trump got in, and the Ghost Ship fire… all these places were shutting down so fast that it was clear [governments] were using Ghost Ship [as an excuse to evict people].”

Intimidated, but knowing that she wanted the building’s tenants to remain, Cheung took the initiative and engaged several like-minded parties in conversation, including the tenants, EastSide Arts Alliance, and supporting organizations like Sustainability Economics Law Center and People of Color Sustainable Housing Network. From this, momentum began to build – and before the tenants at Liberated 23rd could fully grasp their situation, it seemed their fate had already been decided.

“We met up, and we cried a lot – and then we were like, ‘Okay, we’ve got to buy this building,'” recalls Devi. “Publicly, it was not an option for us to not to… [Our organizations] will not survive without this.”

As Liberated 23rd was figuring out their best route forward, Devi recalls giving a tour of the space, and becoming incensed by one long-time Oakland resident’s comments.

“The person was like, ‘Wow, I’ve lived in Oakland for so long, and I never knew this was here… People would never know about this!'” Devi says. “I got so mad… The people who need to know know about it. This has actually been a neighborhood that’s been coming and gardening for 15 years!”

Such invisibility illustrates much of the problem. Although Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf – who recently received national attention for her outspoken commitment to keeping Oakland a sanctuary city – has been a vocal supporter of preserving art spaces, Liberated 23rd was still unable to secure a meeting with city officials.

They had no choice but to take matters into their own hands. In addition to continuing their regular programming, the collective began working around the clock to form alliances and meet with anyone they could, making sure that their leadership was blunt and unapologetic about their intentions, goals, and needs.

Their joint crowdfunding campaign launched in March 2017, with support from newly minted partners like POC Sustainable Housing Network, Northern California Community Loan Fund (NCCLF), and Oakland Community Land Trust, led by Steve King.

“The primary focus… given the short time span that we have, is for the land trust… to be able to pool together the financing necessary to buy the building, [and] to leverage our relationship with the city to bring in some other resources,” King explains in the crowdfunding video.

“The primary focus… given the short time span that we have, is for the land trust… to be able to pool together the financing necessary to buy the building, [and] to leverage our relationship with the city to bring in some other resources,” King explains in the crowdfunding video.

The strategy worked. The campaign received significant press, including a feature on KQED News, and soon government officials and large nonprofits were reaching out, eager to learn their story. The sudden interest was enough to rouse suspicion – after all, elections were coming up – but Liberated 23rd understood the need to be strategic, while still maintaining their political commitments and honoring the space’s history as a long-time organizing center.

“For us, what it means to have an asset is not to have it for four or five years and then to sell it,” says Devi. “To have an asset means we are here long-term, in relationship with the people who have been here long-term. That has to be it.”

Eight months into their crowdfunding campaign, they had raised $90,000, exceeding their initial goal by $20,000. The money was put towards consultant fees, small stipends for organizers, and the building’s $70,000 down payment, to prove to their landlord that they were serious.

“We all have long-term, five-year leases at stable rents, which is amazing for the short term, and then we have two five-year renewals that we can do,” details Devi. “The idea is that, by the end of 15 years, we’ll have paid off the main lender and be able to actually buy the building back from the land trust.”

They now operate collectively under an LLC, which acts as an umbrella for each organization’s unique incorporation structure. Oakland Community Land Trust, meanwhile, serve as an intermediary holding company and provide the long-term guarantee that the land will always be preserved for community space.

In May 2018, six months after the success of Liberated 23rd, Oakland Community Land began another significant project, this time with Hasta Muerte Coffee, a POC worker-owned coffee shop with low-income housing units above it. Just a little over two weeks into their GoFundMe campaign, the co-op had made close to half its $50,000 goal. With additional loans taken into account, they had raised $617,000, which put them at two-thirds of the way to the $938,000 which would allow them to buy the building. The land trust model used by Liberated 23rd can and will continue to be reproduced, it seems.

The Bikery. (Credit: Northern California Community Loan Fund)

[…] A United Cultural Front, Part 1: Models of Space Preservation & Creation from Oakland & Seat… via REDEFINE (2018 Article) […]