Spotlighting Sarah in all her messy complexity, Queen of Glory combines the lightness of academic satire with the weightiness of family drama. With quips about Ghanaian divorces and weddings, Queen of Glory is both affectionate and honest. While Sarah balances the “old country” with the new, Queen of Glory plumbs the fraught dynamics of scattered immigrant families, to deeply moving effect.

As Mensah explains, she wanted to reimagine ubiquitous narratives of flailing young adults. “A lot of times with that quarter-life crisis genre, people are just making enough money to buy the weed and pay the rent, and that wasn’t really my experience,” Mensah explains. “[With] my experience, especially being the child of West African immigrants, there was never going to be an opportunity to kind of coast à la Slackers. So I thought it’d be so interesting to have a character who is experiencing this quarter-life crisis and also is holding it down at work. I don’t think we get to see women be on top of their game in their profession and then perhaps falling apart in their personal life.”

“I interviewed some directors and spoke about the project in the very beginning, and they all had takes that were super interesting, but they just weren’t the film that I was looking to make,” Mensah explains. “I wasn’t doubling down on the strife narrative of what it is to be Black and a woman and from the Bronx. I wanted it to be a little more nuanced – a little bit more dynamic.”

The Humorous Chaos of Bearing it All

Queen of Glory plunges the viewer into the chaos of Sarah’s upended life. Her gruff father’s sudden return from Ghana disrupts her family unit, as well as her plans to move to Ohio with her married boyfriend. For Sarah, the herculean task of organizing a Ghanaian funeral is like being saddled with a second, unpaid job. In one punchy montage, she grows increasingly exasperated as she answers the same questions on the phone, insisting again and again about her mother that “Yes, she has a will!”

This deluge of tasks proves to be great fodder for comedy, but also poignantly reveals how a high-powered career woman might be reduced to an assistant in the domestic realm. In an early scene where Sarah’s aunt accuses her of being “scared of the scale like a white lady” for refusing to weigh herself, Sarah continually sets boundaries that her relatives then disrespect. In these moments, Sarah’s response of choice is sarcasm. Yet the eye-roll or side-eye disappears from Sarah’s face whenever she’s alone, replaced with a lost, faraway look. By revealing the shape-shifting nature of Sarah’s coping mechanisms, Mensah gives a bravura performance informed by personal experience.

“In speaking to friends who have experienced the loss of a parent, one of the things I was struck by is that of course there is this seismic shift happening to you, but then also it is almost comic – the banality of the things that just have to get done, be it paperwork or finding a makeup artist for the cadaver,” Mensah states. “It’s extremely wild that we are asked to do these things and perform these rituals while experiencing this seismic trauma. Sometimes the grief gets pushed to the back because there’s so much to do; you’re almost planning a wedding, not a funeral.

“Especially because in our story Sarah’s an only child, and a female child,” she adds. “It really does all fall on her.”

The most onerous of these responsibilities is deciding whether to sell her mom’s Christian bookstore in the Bronx while managing its sole employee, Pitt (Meeko Gattuso), a muscled ex-felon. Casting was crucial for Pitt’s character. As Mensah explains, “I saw Meeko Gattuso in a film called Gimme the Loot, and he’s so magnetic, so watchable. It became clear to me very early that I was writing [Queen of Glory] with him in mind.”

Mensah then contacted Adam Leon, the director of Gimme the Loot, who also plays Sarah’s boyfriend, Lyle, in Queen of Glory. She wanted to see what else Gattuso could do.

“In Euphoria, he’s playing a drug dealer, and that’s kind of obvious… Here’s this man with a gravelly voice and a lot of tattoos on his face,” says Mensah, “and I’m like: what is the most random location I can put him in? And guess what, it’s a Christian bookstore.”

In their first interaction, Sarah is repeatedly stumped by the fact that Pitt is in charge (“You?” she asks.) Yet Pitt confounds Sarah’s expectations with his SAT-worthy vocabulary, encyclopedic knowledge of the Christian books market, and penchant for baking (of both the legal and illegal variety). Their scenes have a lived-in chemistry, full of the delightful frisson of characters from very different New Yorks colliding. Indeed, while the camera lingers on the shop’s “I Heart Jesus” keychains and rack of right-wing bumper stickers, the nuanced dialogue undercuts any predictable smugness.

An Ensemble Cast to Capture the Richness of the Bronx

As funeral planning takes Sarah on an odyssey through the Bronx, Queen of Glory‘s scope widens to encompass a whole network of relationships. A motley cast of characters cycle through the store, looking for solace or just shade from the sun. In a memorable series of vignettes set to a jaunty score, a nearby man hawks tapes under a banner reading, “African Movies Library & Retail & Whole,” while occasionally clashing with the neighborhood’s teenage boys. As brief as these scenes are, the salesman’s cycles of cheeriness and disappointment are full of pathos. Indeed, the bookstore is the perfect vehicle for these parallel narratives playing out alongside Sarah’s, putting Queen of Glory in the company of many of the best ensemble New York movies.

Among the most memorable of these side characters are the Russian neighbors of Sarah’s mom – the only white people at her wake. Sarah quickly bonds with the sullen teenage daughter, Julia, while helping her harried pregnant mother around the house. In moments like these, the Bronx almost feels like a small town. The juxtaposition of the Russian family also serves to deepen Queen of Glory‘s portrayal of claustrophobic family life. In one scene, as Sarah and her neighbor talk, their conversation is subsumed by children bickering and roughhousing in the foreground. It’s a veritable tableau of domestic chaos. With the audacious cinematography and stylistic ambition of scenes like this one, Queen of Glory distinguishes itself from other quarter-life crisis films, such as Clerks, that Mensah cites as inspiration.

Mensah felt it was important to add more nuance to the portrayal of immigrant families on screen, including those from different ethnic backgrounds. She met actor Anya McDall, who plays Julia’s mother, in an acting class, and discovered that their “struggles were frighteningly similar.”

“She was always getting called in to play, like, Dead Russian Prostitute Number 4,” says Mensah. “What do we usually see in Russian families on screen? Oh, we see crime, maybe some sort of mafia element, trafficking… so I wanted to show a blended family that was of course flawed, but bountiful in love.”

“Growing up, I remember watching my mom, a Ghanaian immigrant, interact with one of her employees who’s from like Bangladesh, or India. The miscommunications, and the shared humor — I was always really struck by that,” Mensah continues. “I wanted to show that yes there are these enclaves, but also, one of the beautiful things about New York is being on the 4 Train and seeing that somebody’s Puerto Rican, somebody’s Bangladeshi, somebody’s whatever, and we all just get on.”

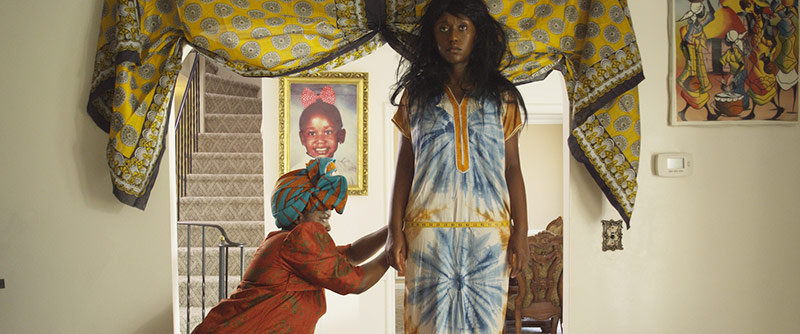

Indeed, as the Bronx pulls Sarah deeper into its orbit, Queen of Glory becomes an ode to the beauty of New York. It’s as though the camera has fallen in love with the geometric shadows of fire escapes and the lush canopy of trees as seen from the train. Shots like these give Queen of Glory the old-school, soulful feel of a Bronx unmoored in time. The film exhibits a deep sense of place; Sarah’s move from her Manhattan apartment to her mom’s home in the Bronx embodies a personal transformation. That both of the primary locations — the family home and Christian bookstore — are owned by members of Mensah’s family in real life further ensures a degree of verisimilitude.

When Sarah’s dad first returns, both he and Sarah seem estranged from the house. They’re both tourists, in a sense; she chides him for losing the key, while he wonders why she’s sleeping on the couch. By the end of the film, however, she’s moved back into her childhood bedroom. The door to her bedroom is left ajar as she leaves a voicemail to her boyfriend; it seems to slice through the screen.

“Hi, it’s me, trying you again, like you said. I may have to stick around here for a while?” Sarah says, every note of her voice uncertain. Yet the viewer senses — perhaps even before Sarah does — that she’ll be sticking around for much longer.