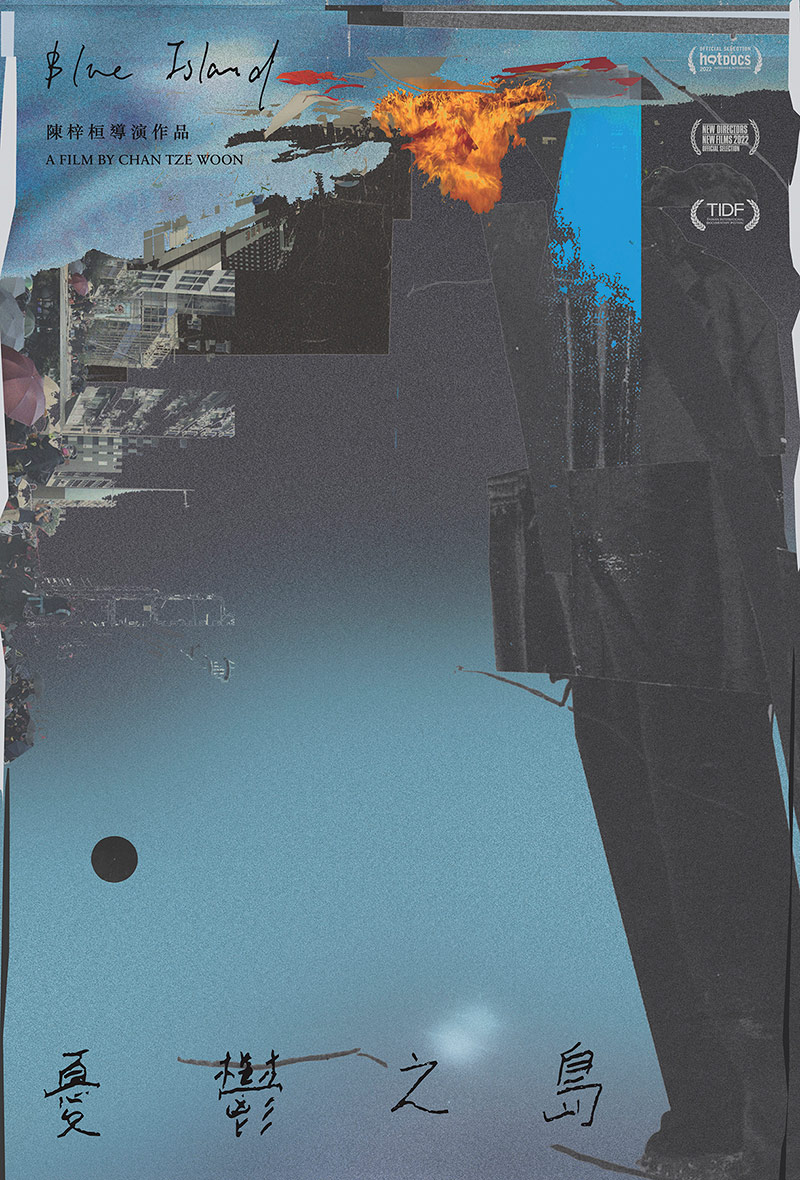

As a documentary with narrative components, Blue Island displays an irreverence towards genre boundaries, even as the ideas it explores are dead serious. The daring conceit of Blue Island is that three young activists, each one active in the 2019 protests, play younger versions of older dissidents who resisted both Chinese and British governments in the past. As they wrestle with how to faithfully embody memories that are not their own, the past reverberates into the present with resounding force. Facing the specter of the 2020 National Security Law passed in response to the 2019 protests — which criminalized verbal support for Hong Kong sovereignty — these activists are forced to constantly weigh sacrifice against safety. And the viewer feels it all.

For Chan, such disorientation was precisely the point. He says, “I’m trying to blur the boundaries between documentary and fictional film. You keep asking the question, ‘Is it a documentary or is it real?'”

In part because of such ambiguity, Blue Island is a heady, deeply rewarding watch. Moving beyond attention-grabbing but fleeting headlines, the film constructs a sweeping history of dissent in Hong Kong over the course of decades, anchored in poignant personal stories.

Fact & Fiction Flow in Parallel

Blue Island begins with the story of Hak-chi Chan, a soft-spoken intellectual who survived the Cultural Revolution before swimming to Hong Kong in 1973. Ansom and Sin, a couple active in the 2019 protests, recreate his escape, transforming from gangly students to hardened survivalists. These reenactments not only place the young activists in a lineage of resistance, but also let Hak-chi Chan correct the historical record on himself. During a sequence set on a forced labor camp, complete with sweeping vistas of the highlands and booming speeches, Ansom breaks the fourth wall to ask him, “Was the mood like this back then?”

Shaking his head, Hak-chi Chan says, “No, not so fervent. We didn’t chant slogans like that.” Instead, he explains how he went to the farm to spare his family from an even worse reeducation camp. As committed as each actor is to accurately portraying the past, it is these in-between moments of doubt — these departures from the script — that are perhaps most revealing.

As Chan describes, his subjects had such a strong connection to the material that he barely needed to coach their acting. “Their emotion or what they’re facing is quite similar to the protagonists,” he says. “Actually most of them are very depressed after 2019 because they think the protests have failed, and some are asking if they have to go somewhere else to search for freedom. Through the process of reenactments, we can make connections with the old history of Hong Kong, but at the same time try to understand the actors themselves. So it’s two-layered.”

Compared to the other two activist pairs profiled in the film, Kelvin and Raymond have a more formidable gulf of understanding to bridge. Then-teenage Raymond participated in the 1967 riots against Hong Kong’s colonial government, and today is a successful businessman who leads patriotic tours for students. Yet many Hongkongers now look askance at the 1967 protests supported by the Chinese Communist Party, viewing the Chinese government as no longer an underdog, but rather a new oppressor. At a ceremony for “martyrs” of the 1967 protests, Raymond clutches flowers while the speaker promises to root out “anti-Communist” and “anti-Chinese” elements from the body politic.

As Chan explains, the meaning of the 1967 riots changed radically after the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997. He says, “In 1967, those rioters, or protesters if you want, actually were in a minority. At that time, Hong Kong was a British colony, so what they are fighting for is that they want the Chinese Communist Party to take control of Hong Kong. How they think about the protests nowadays is so much different from that time. So it’s very strange for me. But at the same time, their political stance is still the same — in the past and now, they are very pro-Communist Chinese Party.

It also makes me think about ourselves, and if in the future we will change our position thirty or forty years later,” he adds.

Photo by Joseph Chan on Unsplash

A Historical Timeline of Hong Kong Protests from 1967 to Present

1967: The May riots began at a flower factory where workers were facing wage cuts and indiscriminate firings, but quickly spread. The unrest ranged from union-organized strikes and marches to bombings and arson. In total, 51 people were killed and upwards of 800 were injured. The pivotal role played by an affiliate of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in orchestrating the riots has only recently come to light. NYTIMES

1989: The Tiananmen Square protests began in April at a Beijing memorial for the CCP’s general secretary, Yaoang Hu, before spreading to other cities. Students went on hunger strikes to support the liberal-minded Hu’s reforms, calling for free elections, free speech, and an end to government corruption. Upwards of a million protested in the Square, with Gorbachev’s earlier visit bringing Western journalists to the city. CCP leader Deng Xiaoping, a hardliner who opposed concessions to protesters, declared martial law in Beijing in late May. Three major Hong Kong protests were attended by more than a million people each. Ultimately the government cracked down in a brutal fashion, storming Tiananmen Square on the night of June 3rd and killing thousands of protesters.

1997: Under the agreement signed by Margaret Thatcher in 1984, Hong Kong was to become a “special administrative region of China.” The official handover happened on July 1st, 1997, when Britain’s 99-year lease on the territory ended. THE GUARDIAN

2003: The Hong Kong government, led by former shipping magnate Chee-hwa Tung, introduced a security law to stiffen penalties for sedition, treason, and secession. While less harsh than the rarely-used British colonial laws, activists nonetheless sounded the alarm. More than 500,000 citizens donned black clothing and marched from Victoria Park, in what was the largest protest in Hong Kong since 1989. Consequently, the law was canceled and Tung resigned. NYTIMES

2014: The inciting event for the Umbrella Movement was the Hong Kong legislature’s proposal to change how the city elected its chief executive, previously chosen solely by the city’s pro-Beijing elite. The government promised to finally grant the “universal suffrage” enshrined in the 1997 constitution by letting Hongkongers vote on approved candidates. Pro-democracy activists saw the proposal as indistinguishable from the status quo, however. Led by the 15-year-old student leader Joshua Wong, they staged a two-month occupation of the city’s financial district. The movement took its name from the umbrellas activists used to shield themselves from police’s pepper spray, tear gas, and rubber bullets. In 2015, the pro-democracy faction of the Hong Kong legislature prevented the proposal from taking effect, but activists’ greater demands went unmet. NYTIMES + ECONOMIST

2019: The historic 2019 protests were sparked by the February introduction of a bill making it easier to prosecute Hongkongers in mainland China. Ostensibly meant to deal with “fugitives,” the bill opened the alarming possibility that activists might be extradited to China for criticizing the government. In March, 12,000 attended the first demonstration, but the movement quickly grew in scale; by June 9th, more than 500,000 showed up. Following the widespread use of rubber bullets and tear gas by police, the protests expanded their focus to encompass police brutality. The next few months saw major escalations, including a tumultuous protest on the 22nd anniversary of the handover to China. While the extradition bill was formally withdrawn in October, confrontations continued, most notably when 1,100 activists and students were arrested at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. THE ATLANTIC

2020: In May 2020, China’s legislature issued a national security law on Hong Kong outlawing sedition, treason, and secession. Since then, around 200 people have been arrested under it. Despite the law’s stifling effect on speech, most of the thousand-plus people sentenced in connection with the 2019 protests were charged with unlawful assembly or possession of a weapon (often a laser pointer). A report from May 2022 found that there are now 590 political prisoners in Hong Kong, a dramatic increase from the years preceding. Among the recently sentenced, 73% are aged thirty or younger. ECONOMIST

2022: Hong Kong held its election for chief executive in May with only John Lee, the former Security Bureau chief who spearheaded the 2019 extradition law, on the ballot. As a member of the government, Lee helped crush the Hong Kong National Party in 2018, which advocated independence. Lee has made combating “foreign interference” his mission and denounced arrested journalists as “evil elements.” His rhetoric and history suggest a troubling immediate future for Hong Kong, yet activists continue to agitate for true democracy. THE ATLANTIC

Photo by Chi Lok TSANG on Unsplash

Friction Between Worldviews

Rather than just a mere gimmick, the format of reenactments turns out to be the perfect vessel for these clashing visions of Hong Kong. In one particularly mind-bending scene, Kelvin plays a younger Raymond as he is being interrogated by a British officer.

“You grow up in our colony; you studied in our schools. So then why are you fighting against [Britain]?” the officer scolds.

But when Chan repeats the refrain back to Kelvin, he replaces “Britain” with “China.” In his palpable nervousness, Kelvin quite literally embodies a contradiction, playing both sides of a love-hate relationship with China that has soured as the Chinese Communist Party cracks down on ever-more freedoms.

Perhaps because of this friction between their worldviews, the interactions between Kelvin and Raymond prove to be especially bursting with insights. It helps that they share the singular experience of being criminalized for their words. In a break between reenactments, the two sit against the wall of a mock jail cell, disguised by darkness. While Kelvin tries to face the prospect of jail time stoically, Raymond cautions against romanticizing prison, warning that it can grind down anyone’s idealism.

This scene was a serendipitous encounter, says Chan. “My original plan was for them to be separate, but I suddenly had the idea, ‘Okay, maybe they can start a conversation with each other and talk about their own political thought.'”

“So we put them in the cell, we left them for one hour, and in the beginning Raymond talked quite a lot about his experience and Kelvin [was] kind of shy,” he continues. “But in between, we had a break, and I asked Kelvin, ‘Maybe you should share more about yourself,’ and actually, [this] is the first time he introduced his experience in the 2019 protests to Raymond. When he sees the young Kelvin there wearing the costume, somehow there’s some connection between them. It is like Raymond’s past connected with Kelvin’s future.”

In stitching together seemingly disparate protest movements, Blue Island illuminates recurring motifs of resistance. In particular, the student-led protests at Tiananmen Square in 1989 resonate into 2019 and beyond. Kenneth, a lawyer who risked his life in 1989, seems to draw a kind of psychic strength from young activists like Keith, who plays him in reenactments. At a 60th anniversary event for the Federation of Students, which organized the Tiananmen Square protests, Kenneth is almost an avuncular figure. He treats the young guests in attendance as equals of the veterans of 1989, rather than relegating them to the “kids table.” But fighting the gravity of years of democratic backsliding, Kenneth’s shifting facial expressions betray a deep-set weariness.

Blue Island doesn’t spell out all these 1989 to 2019 connections explicitly, instead rewarding the eagle-eyed viewer. The same black and white banner bearing the message, “The People of Hong Kong Support You” shows up in footage from a 1989 march, at a vigil attended by Kenneth, and in a corner of Keith’s cramped studio apartment. The cumulative effect is surreal, as though this banner has skipped in time. In this context, China’s ban on the city’s vigils in remembrance of Tiananmen Square, a tradition for thirty-some years, is an admission of their fear of people remembering the past. Keith, for his part, openly compares cops’ brutality in 2019 to the People’s Liberation Army in 1989, which infamously mowed down protesters with tanks.

While footage of the 2019 protests is readily available online, Blue Island goes beyond merely repackaging existing video, instead placing these events in a longer, more epic trajectory of Hong Kong resistance. Chan describes filming those 2019 events as a challenge — one that inspired him to find innovative ways to tell this story.

“In 2019, they are hiding their faces [with masks], they are wearing black bloc, so you cannot distinguish anyone. Also, they are doing it everywhere in the city; it’s not only one or two places. And every day is more tense, with more confrontation between the police and the protesters,” he explains. “So for me as a documentary filmmaker, it is quite difficult. I’m making footage that I don’t know how to use.”

“In a protest, it is very timely; we have to tell the story immediately — but for documentary film, eventually it is more about how to make things become timeless,” he notes.

Blue Island‘s slow-burn approach, which involves assimilating an array of perspectives and timelines into one cohesive whole, is especially valuable given how rapidly events in Hong Kong are changing. John Lee, a former deputy chief of police known for helping pass the 2019 extradition law and sanctioning police brutality towards protesters, was elected in May, making the future of Hong Kong even more uncertain.

“Nowadays, being a Hongkonger, you can see your home city changing so fast, and the situation is deteriorating, and it seems we cannot do anything. We are depressed, we are angry. Actually the Chinese title of this film is something like ‘Depressing Island,'” he says. “As Hongkongers, we are sure we have the ideal Hong Kong; we have our imagination about what Hong Kong should be or what Hong Kong is, but somehow we never have the chance to control our fate in this city.”

Yet Blue Island‘s reenactments do exactly that. They wrest control of Hong Kong’s history and destiny away from British or Chinese governments and into the hands of angry, defiant Hongkongers. While much has changed since Blue Island was filmed in 2017, the viewer can easily imagine its indelible characters continuing the perennial fight for democracy long after the credits roll.

Ω