Jaleesa Johnston and artist Tasha Ceyan in Monument to 6%, 2015, performance (01:00:00). Photo by Christina Marie Walley.

Moving Between Mediums

Johnston’s ever-growing multitude of mediums includes performance art, installation, photography and videography, sculpture, drawings, and collage — but she first began artistically conveying the innate, deeply feminine wisdom that resides in the body through photography.

At first, Johnston used herself as the subject of many of her photographs, but during graduate school, a professor challenged her to get rid of the camera as “middleman.” This advice launched her into exploring the experimental qualities of live performance art.

“It wasn’t until I moved up to the Pacific Northwest that I suddenly became interested in movement and dance as a part of my [art practice] — because before, I always felt like there’s an action, and I’m doing an action, and… that’s it. I didn’t see it as ‘movement,'” Johnston recounts.

This shift in understanding occurred after Johnston encountered the Portland-based collective, Physical Education, and she took two workshops at Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA) with choreographer Takahiro Yamamoto. She recalls a particularly influential exercise, where they were directed to walk through a giant room with their eyes closed and rely on another person to guide them.

“What stuck out to me about that experience is… when I was walking and had my eyes closed, I could sense other people moving around me. I was constantly worried that I was gonna hit an end — hit the wall or… the edge of the room — but I never did,” shares Johnston. “The space felt infinite.”

Johnston likened that moment to being dead. Despite not being able to see others, she was sensing them and felt they were in communion together during the exercise.

“It was in that moment that I was like… my body is capable of offering me so many different types of rich experiences that I wasn’t open to before,” reflects Johnson. “And it’s simply because I just allow[ed] myself to be present in this moment of moving.”

Physical Law, 2017, performance (00:20:00), photo by Caitlyn Clester

From then on, Johnston fell in love with discovering what else she could do with her body. She found that she could not only draw inspiration from different facets of her body and being, but that movement and performance were important modes for her to learn and conduct research.

“If you talk to a lot of dancers [or] movement artists… I get the sense that [movement] is also their research practice… it’s their art and their research, all at the same time,” shares Johnston. “When you’re watching others move, there’s a lot that I gain from that. When I’m hearing others move, there’s a lot that I gain from that. And then, when I’m moving, I’m always learning something new.”

Johnston notes that when one taps into their body as they move through space, they notice smells, sounds, and other sensations to a heightened degree — well beyond what they might experience in the normal day-to-day.

“If you’re just fluctuating between all these different forms of knowledge or access points for knowledge, you learn something… about your external and internal environment…” shares Johnston. “If I’m interested in my experience as both subject and object, it only makes sense that I’m constantly researching the phenomenon of moving through space and time as this subject-object [myself].”

Early in Johnston’s career, she had a narrower perspective on performance art, which included a clear division between object and subject, or performer and audience.

“But now, I would say that I think I really do feel that there’s a kind of consciousness in everything,” says Johnston. “I think we’re always inhabiting both subjectivity and objectivity — that we are consciousness, but we’re also here in bodies that are very pliable, and bodies that are constantly shifting and changing and evolving and moving.”

Ivory and Flesh, 2017, 6 x 6 in, collage on wood panel from Between Contact series

Carried On, 2017, performance (01:00:00), photo by Kalaija Mallery

Uses of Discomfort

Many of Johnston’s performances are durational and place physical stress on her body. In 2015’s Monument to 6% performance, she bore the weight of heavy stones to meditate on “the continual state-sanctioned violence targeted against Black and Brown bodies.” In 2016’s What’s Passed Down, she periodically submerged her head and body in a bathtub, using water as a signifier for the Middle Passage — and in doing so, emphasized both individual and collective generational trauma.

For 2017’s Carried On, Johnston worked with artists Fernanda D’Agostino and Elisa Nyassom, in a collaborative performance that used “melting ice and the negotiation of bearing weight as tools for communicating the trauma and healing cycles of living with sexual violence.” Each artist held sacks of ice in different positions while voicing stream-of-consciousness monologues, expressing their immediate thoughts and experiences of the shifting weight of the ice cubes as they melted. Describing this transformation of a solid to liquid, in real time, the performers’ intention was to articulate the difficulties and “complexities of healing and voicing truths.”

Despite this track record of physically challenging works, Johnston notes that her relationship with discomfort has evolved over time.

“During a durational performance, I felt like I needed to be exposed or rubbed raw so I could really get to the heart [or]… the core of the performance…” recalls Johnston, who previously believed that discomfort was the space where she could make the most emotional or spiritual impact. “I felt like I had to bring my walls down, and in order to bring my walls down, I had to be uncomfortable; I had to be pushed into a place of discomfort where I can struggle outwardly in front of people.”

Discomfort is still an important practice for Johnston, but she has begun considering it in ways beyond the physical.

“Maybe it doesn’t always have to be these really hard, painful endurance-based moments, but maybe they can be really gentle, embracing, tender, and loving,” says Johnston. “There’s a discomfort there too, that’s worth exploring and thinking about.”

Circles (from Encounters), 2018, 8″ x 8″, pen, gouache and human hair on watercolor paper

Origin (from Encounters), 2017, 5.5″ x 8.5″, pen, gouache and human hair on watercolor paper

Explorations of Blackness

One of Johnston’s current explorations is a collage series on Black queer love that has been in the works over the last several years. Describing how love and its infinite qualities emerge in this series, Johnston notes that some parts of her still cringe at what can seem like “corny” themes. These physical responses, she realizes with great awareness, clue her into knowing that these discomforts also touch tender spaces within her.

“I feel like our bodies contain more knowledge than we’re aware of. And I feel like we don’t always have all the tools — or we’re not aware of all the tools available — to access that knowledge,” says Johnston. She explains that tapping into her body allows her to move beyond residing in the brain and in logic, offering her wisdom and insight into life that does not abide by linear or concrete structures.

“There’s something kind of reassuring [in]… defying all these straight lines, and this idea of progression and linearity — and instead, viewing things as more cyclical,” she says.

Many of Johnston’s pieces are rooted in a quality of seriousness, sinking down into unprocessed emotions that tend to become buried in the subconscious. She extrapolates these shifting feelings through various lenses and experiences of Blackness and femininity, leveraging her own lived experiences as a Black woman. Her pieces serve as concentrated points of attention, like acupuncture needles to wounded muscles, bringing blood flow to intergenerational wounds so that they may mend and heal.

Johnston reflects, “If I think about the idea of Blackness and how it was created, and the marking of different African bodies… it’s to create this category that unifies… many different groups of people; that paints all of those people the same — and then further places those bodies towards a particular kind of objectification that lends itself to violence… [and] a particular kind of power structure.”

For Johnston, though society’s initial categorizations of Blackness were set up to “heavily define” or “restrict,” Blackness is continuously being redefined by Black communities. The lack of a settled definition and its constant change from generation to generation has become something that is freeing for her.

“I think ambiguity, falling in between the cracks, [and] working in the in-between of things, for me, has always been where the most freedom is… because I’m not beholden to any one thing,” Johnston says.”There’s so much possibility in those spaces. There’s also a lot of forgiveness for me to be human and to change my mind and to think differently.”

“There’s also freedom because I’m not really expected to uphold any particular kind of tradition,” she continues.”So as a Black person, I can literally create myself now… there’s a kind of freedom there that I’m like, ‘Might as well embrace it.'”

Johnston describes this transformative shift as turning a weapon into medicine. Embracing her own meaning of Blackness has led her to an understanding that it is something that can never be flattened. With that knowledge comes the power for radical healing.

Installation shot of Holding Space at METHOD Gallery in Seattle, Washington

Extensions of Nature

In August 2022, Johnston’s installation, Holding Space, was hosted at Method Gallery in Seattle’s Pioneer Square neighborhood. In the center of the room, a large cream-colored cheesecloth sack hung heavy with a generous amount of soil, suspended in the air with ropes woven from braided brown and black synthetic hair. Directly beneath the torso-sized sack, a mound of dirt spilled out onto the floor. Peering closely, one could see white plant roots scattered throughout.

The entire installation was a practice in honoring life’s cyclical nature. Accompanying the center installation were other works that Johnston had created at various times in her career, including Tether, a video art installation that she began working on in 2017. It features two silhouettes of Johnston moving in jerky stop-motion-like movements across the screen, tethered to a tree by a rope made of synthetic hair — the same hair rope that Johnston made for her 2017 performance, Physical Law<, and used again in the Holding Space installation.

Tether has since manifested in a single-channel video in which two silhouettes are tied to a tree using the same hair rape.They oscillate between moments of stillness and rapid movement — frozen in different positions for several heartbeats before shifting swiftly into the next, in a dynamic struggle that is reminiscent of lynching. Sometimes, there is a grasp and tug at the rope; other times, a head-bowed surrender against the trunk of a tree. As Johnston describes, Tether is a working title for a piece that was originally intended to be a live performance piece.

“There’s still no clarity for me around why I’m doing this, what exactly I’m trying to do, [or] how it’s going to happen. [I] only know that I had a particular vision in my mind of what it’s going to be in the end, a kind of inkling of what I’m working towards…” explains Johnston, who is committed to the eventual Tether performance, despite her lack of clarity around it.

“Oftentimes, [the process] is just sort of intuitive…It’s just being willing to allow the process to unfold how it’s going to unfold.”

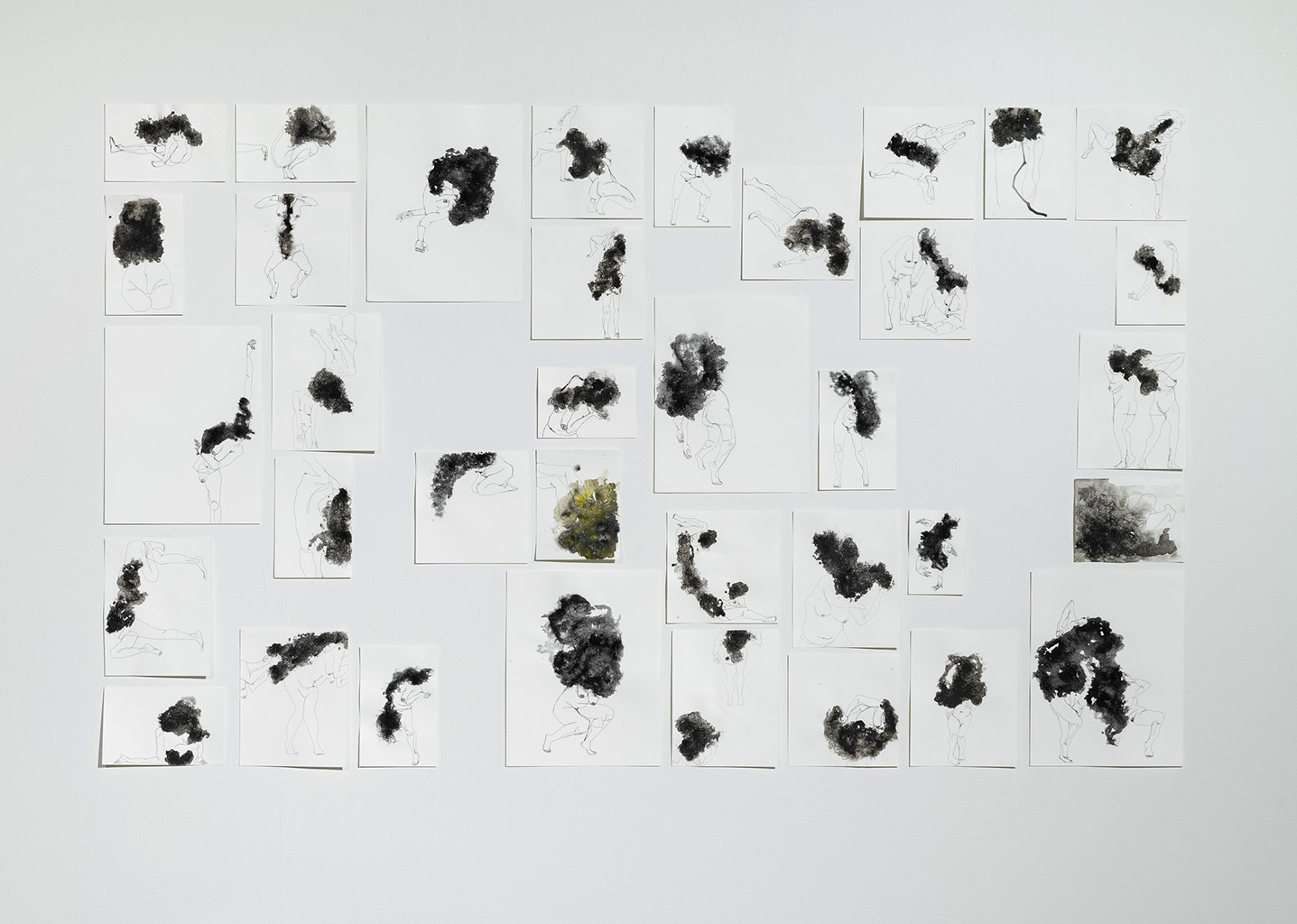

The third component of Holding Space was a mixed media series, Encounters. Dozens of drawings using pen, gouache, and human hair on watercolor paper were arranged along the room’s perimeter — and from afar, they appeared as a cluster of dark stains along the gallery’s blank white wall. As one approached, thin pen lines became more visible and human figures emerged, bending and stretching in different positions. Their facial expressions were obscured by their hair, each wildly organic in shape and feeling.

“[These] drawings are moments of me encountering other versions of myself through time — past, present, and future,” says Johnston. “[I wondered] what would it look like for all these versions of myself to meet… and wrestle with each other or support each other.”

Installation shot of Encounters series at Oregon Contemporary. (Photo: Mario Gallucci)

Such themes framed the entire Holding Space show, which Johnston used as a way of displaying her artistic evolution.

“For me, it’s not productive to be like, ‘Well, I’ve learned and grown as an artist… and that [past version] is no longer relevant…'” explains Johnston. “It’s all relevant, and I feel like if I’m gonna be kind to myself, part of that kindness is accepting all these different versions and facets of me.”

While Johnston’s early career was deeply rooted in theory, and she still loves to engage with complex concepts of Blackness and femininity, she also recognizes that in the current cycle of her practice, she has momentarily loosened her grip on the theoretical.

“When I came up with the Monument to 6% performance, I found theoretical backing for this and that and really tied it to all these other great thinkers — Black thinkers…” reflects Johnston. “While that’s still important to me, right now, I’m a little more intuitive, and I’m not really worried about who it’s in conversation with yet.

“But I know that at some point in the future, I’ll circle back…” she continues. “[Life is] cyclical, and so you have to hold space for all these versions of yourself because that version will come back… so just get comfortable with all the parts of yourself.”

Ω

Tether (still), 2021, 00:04:00, single channel video

Unknown to Me (from Encounters series), 2019, 8″ x 8″, pen, gouache and human hair on watercolor paper (Photo: Mario Gallucci)

Installation shot of Holding Space at METHOD Gallery in Seattle, Washington