“That had always been a part of just me starting to make things from an early age,” explains Craven, “even though I had no concept of what art was, let alone contemporary art — let alone anything else.”

“[I realized], ‘Oh, to be a painter in New York, I’m going to have to hang out with painters and talk about paintings and reference the history of painting into my work — and that just wasn’t what I was personally interested in,” he recalls.

That epiphany paired well with the grad school environment, which encouraged Craven to experiment outside of his comfort zone. That, coupled with a blissful coincidence, led Craven to the discovery of his current medium.

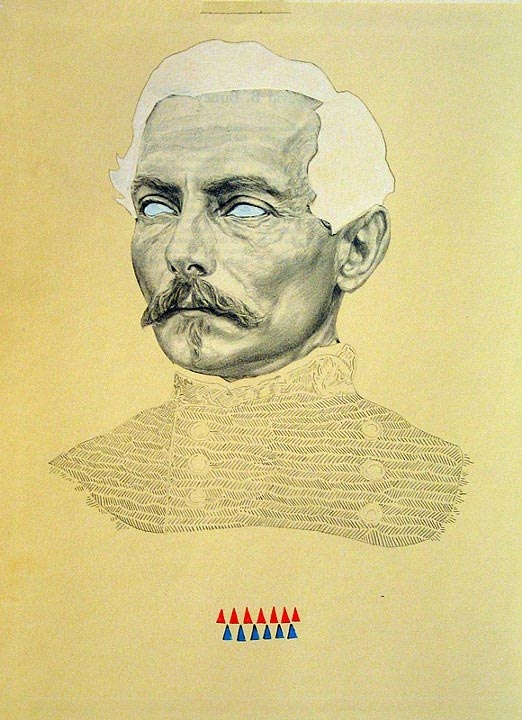

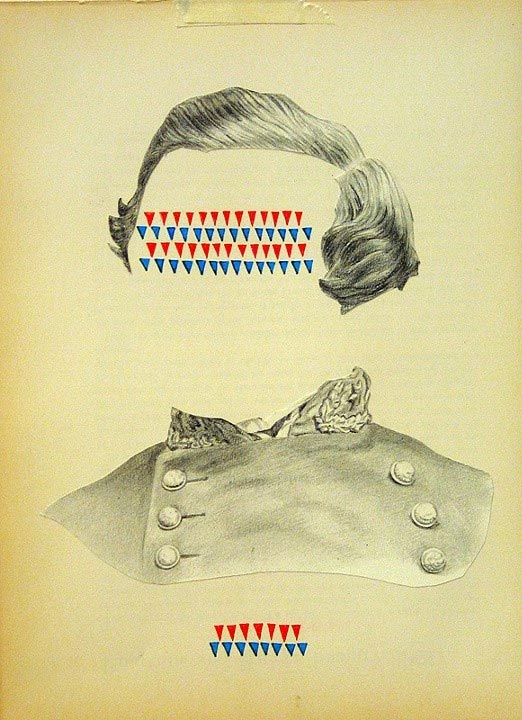

“I went back to working with paper and making ink drawings, when another student — a friend of mine I was in grad school with — gave me a stack of frames he had. He was like, ‘Oh, you might want to frame your drawings,’ and inside the frames were all these American history illustrations,” Craven remembers. “And because I was in this place where I was just trying to figure out my direction, like, I just took them out and started drawing on top of them.”

Craven crafted multiple pieces after these experiments, and much to his surprise, the responses were overwhelmingly positive. During an open studio at the end of his first semester, a gallery in Chelsea was so impressed that they offered Craven a solo show for the first body of collage work’d he ever made. He had found a medium, it seemed, which offered him a different kind of history than that of the painting world. He became enamored. Mixed media and collage resonated much more with him, and the discoveries about just who he is as an artist have been a “series of events” since then.

– Matthew Craven

Breaking New Collage Frontiers by Honoring the Old

“I had a brief moment where I was sourcing things from the internet, and I [realized], ‘No, I have no connection to this whatsoever…'” he explains. “When I was finally like, ‘You are a collage artist,’ I wanted to treat it like I was a sculptor. Materials are important.”

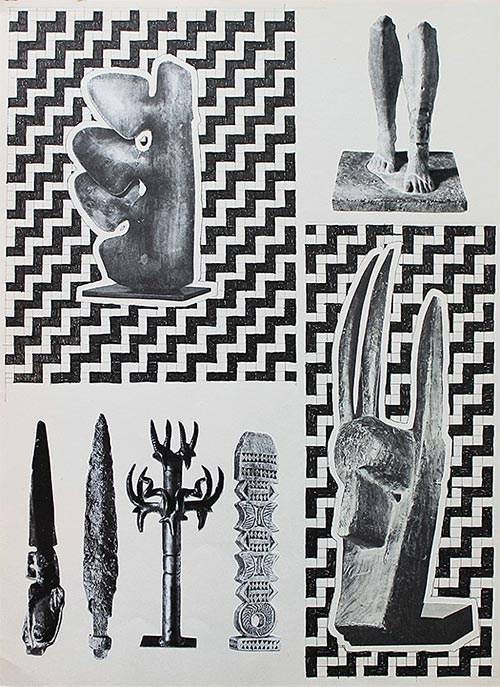

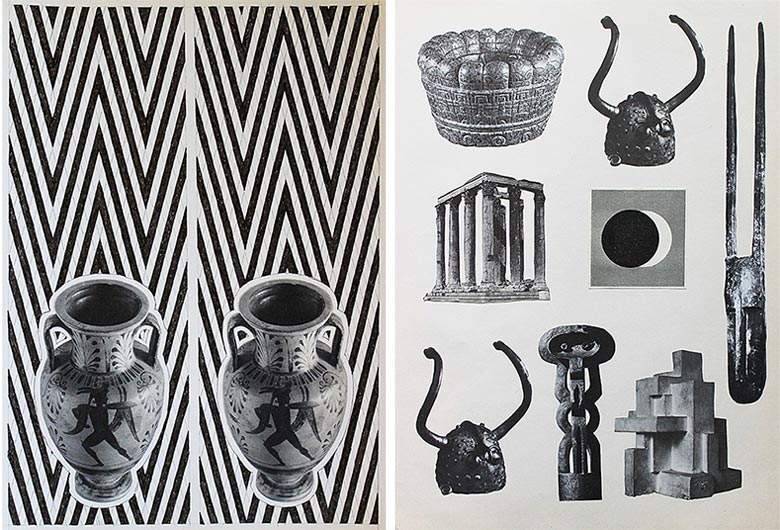

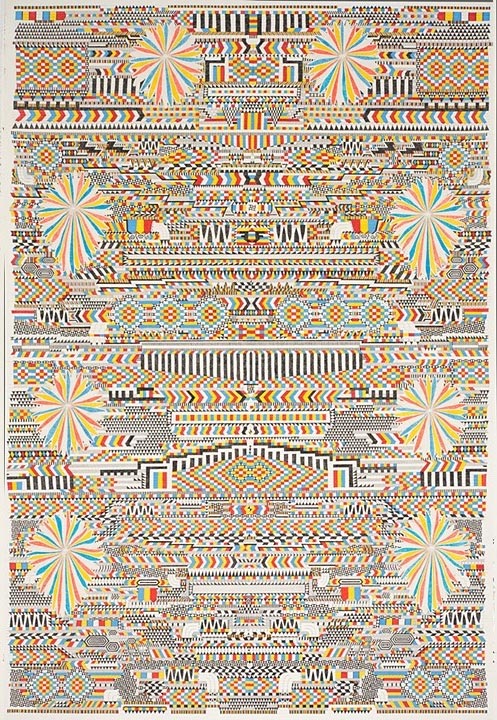

He began by establishing a firm set of stylistic ground rules for himself. First, he opted to never use National Geographic or any magazines that were glossy — “I just hated that aesthetic,” he admits — which automatically dismisses a large amount of his potential source material. He also vowed not to make pieces just to be “psychedelic”, which is often the tendency for other artists.

He began by establishing a firm set of stylistic ground rules for himself. First, he opted to never use National Geographic or any magazines that were glossy — “I just hated that aesthetic,” he admits — which automatically dismisses a large amount of his potential source material. He also vowed not to make pieces just to be “psychedelic”, which is often the tendency for other artists.

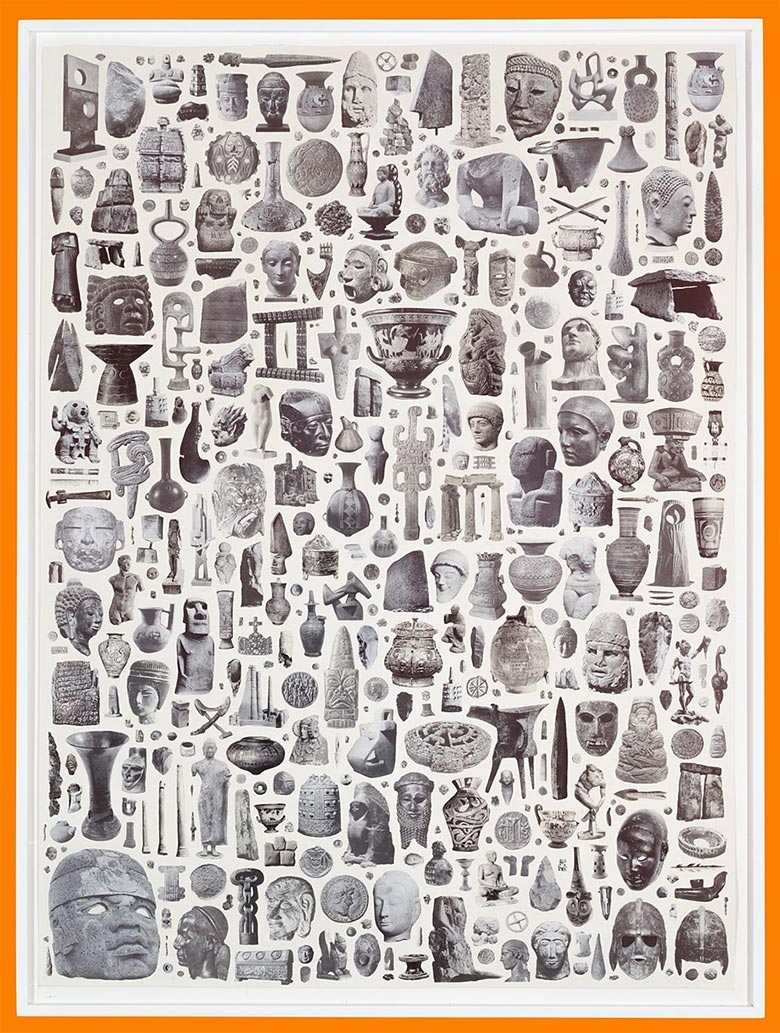

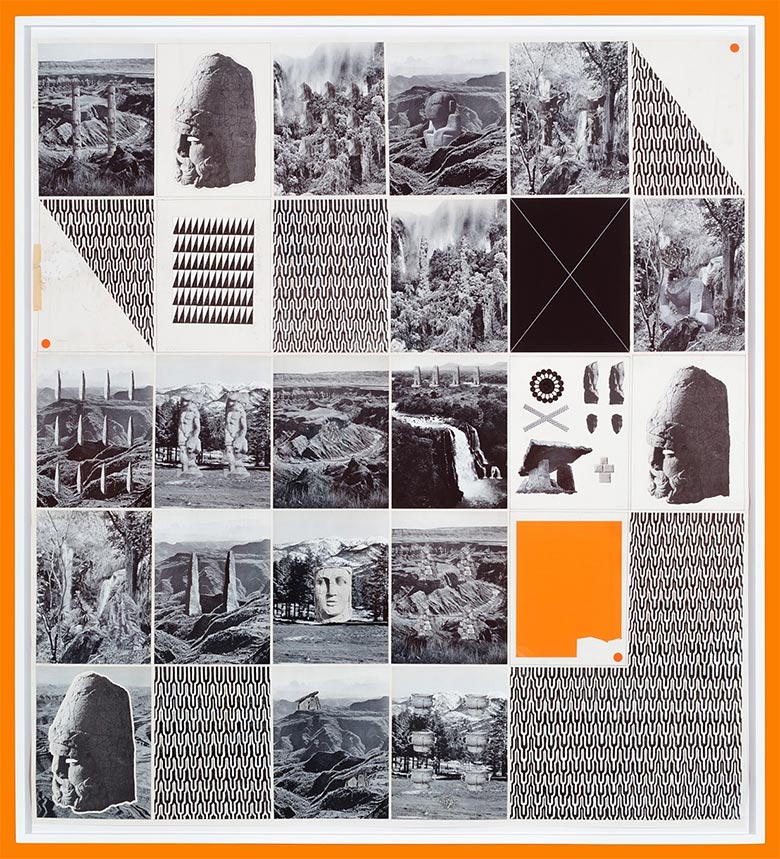

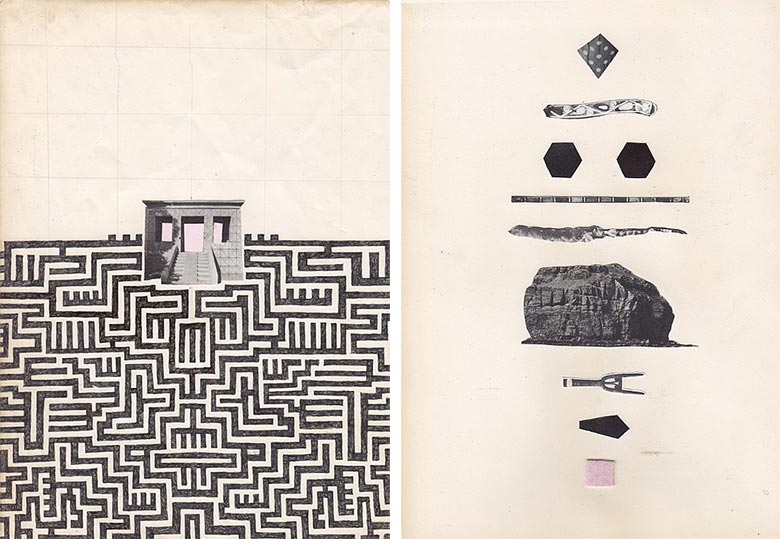

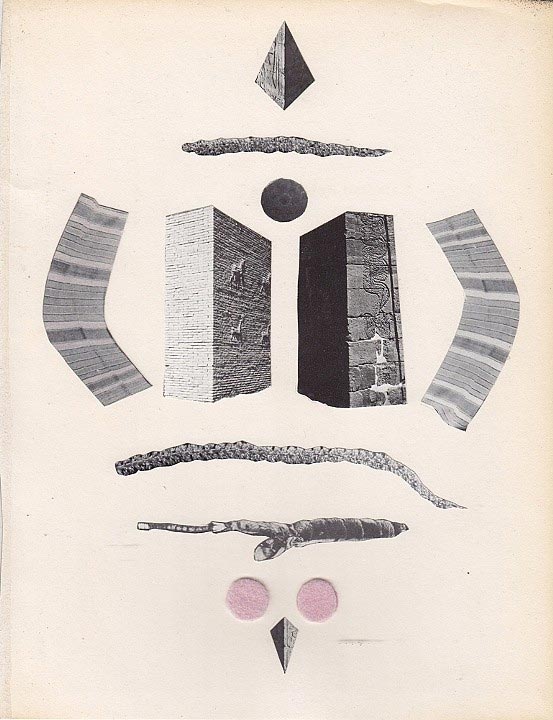

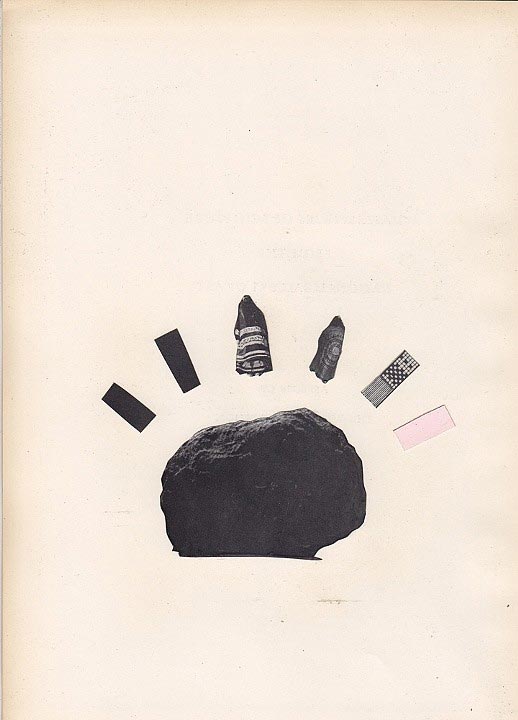

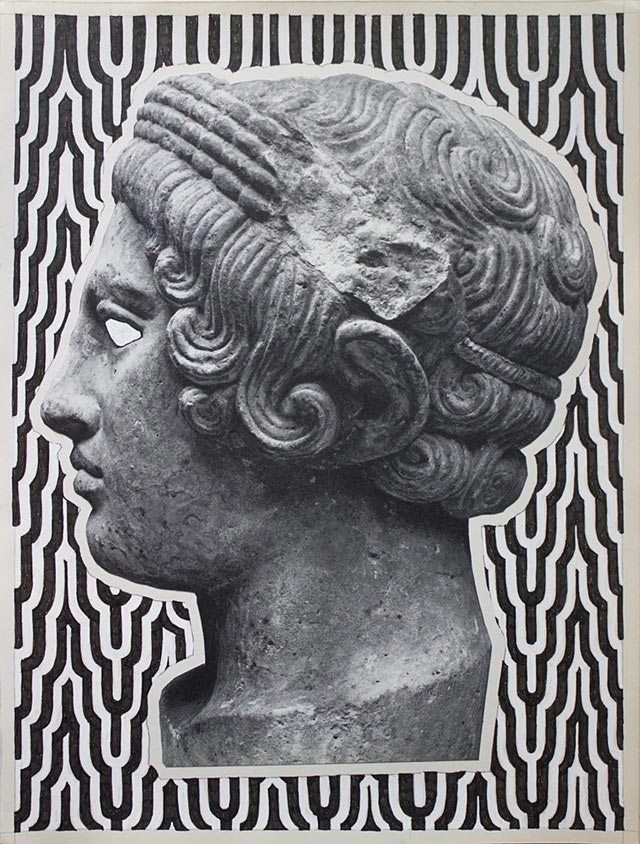

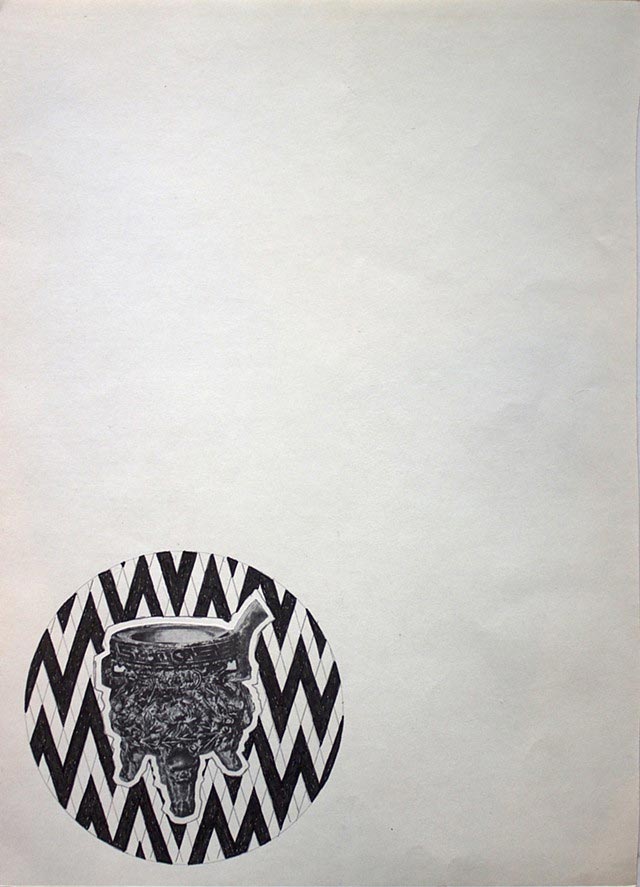

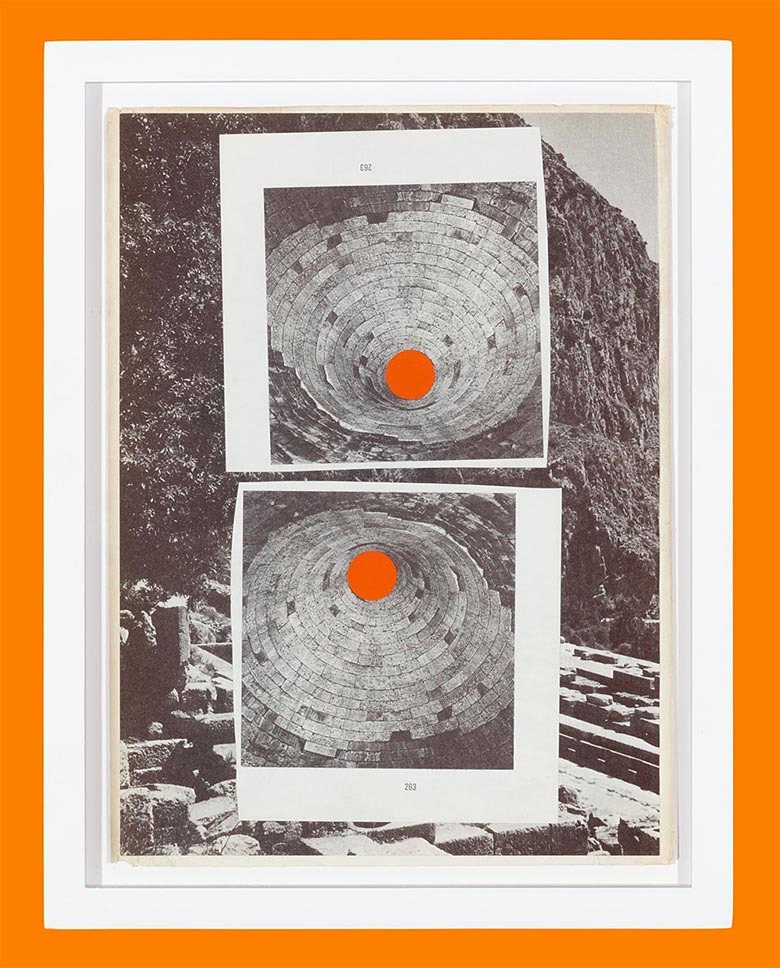

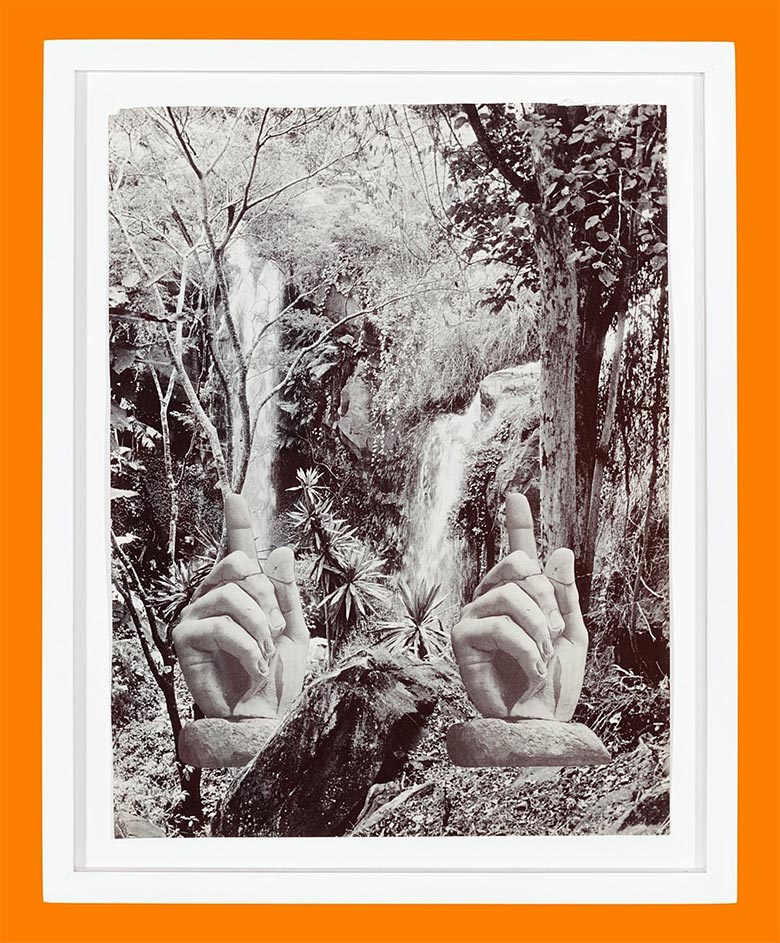

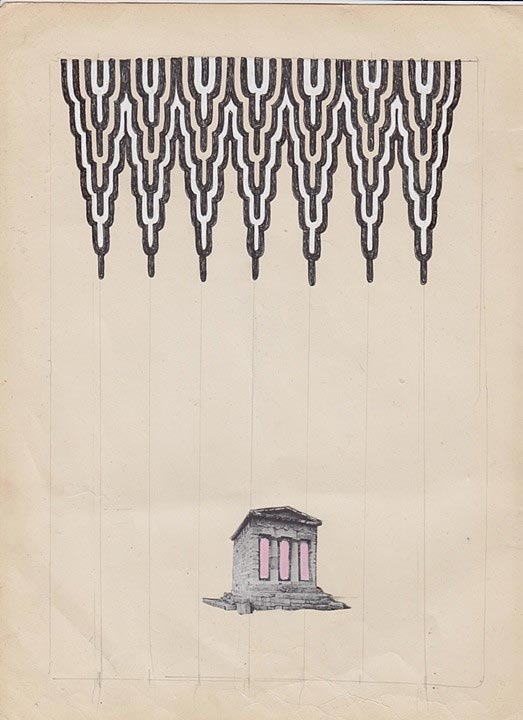

Following these parameters has ensured Craven a level of sophisticated cohesion rarely found in modern collage. Details are everything. Though his images look plenty impressive on the internet, it is in-person that viewers will truly appreciate the tactile nature of the smaller elements, such as the paper stock, the scraggly line work, and the careful way in which Craven applies images to paper with “very toxic but very permanent” spray adhesive, so as to almost erase all of the three-dimensionality usually found in gluing images to paper.

“When you’re taking such care in taking the paper and the collage material and you’re putting it on right, it almost becomes seamless. When I reconstruct an image on the size of a book page, it can look like an actual book page,” says Craven. “It doesn’t look like a bunch of things smashed together and glued together. It’s all the little things that really matter to me.”

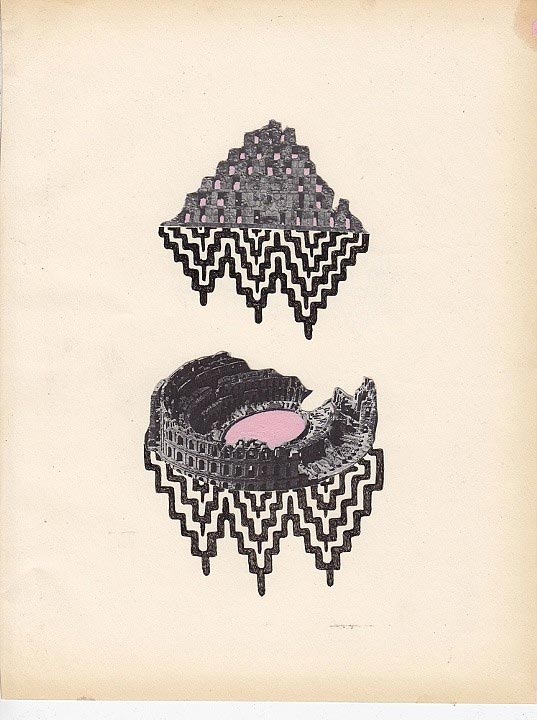

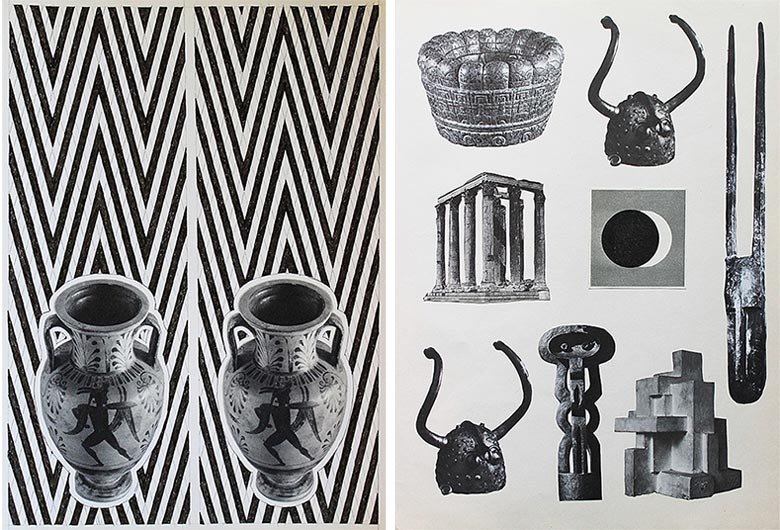

Many of Craven’s pieces feature hand-drawn repeating elements — but those that aren’t, such as the duplicated usage of iconic statue heads from cultures long gone — are, quite impressively, never photocopied replicas.

“If I use the same image more than once, that means I’ve found the same book more than once. There are certain books that I have forty copies of,” Craven says, detailing how important it is that originals are ever-present in his works.

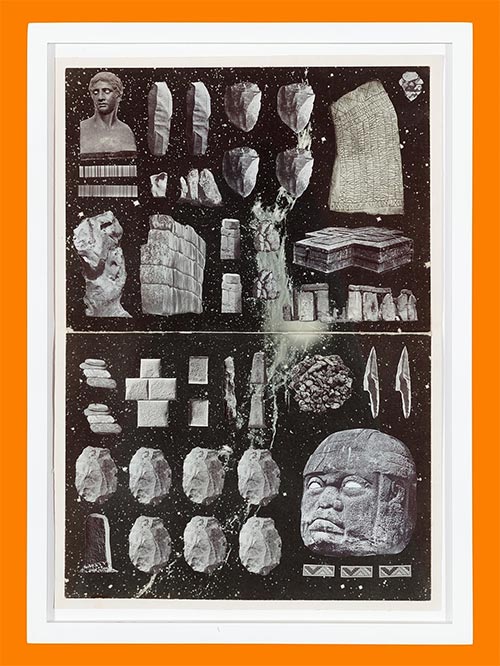

Just as important is the paper stock upon which his collages are mounted. Smaller pieces may be glued on the inner and outermost pages of old textbooks, and more recently, Craven has begun creating impressive large-scale pieces by seeking out old movie posters. Their age-worn stains, dirt, tape residue, and off-white colors add a subtle grit, which furthers Craven’s style visually and conceptually.

“I was taking such time to find images from old books and the quality of the paper was really important, and I would adhere it to a new piece of paper and it would completely change the whole thing,” he muses, proving that the hunt for raw materials is a thoroughly considered philosophical choice. “I want everything to have its own history — even my materials I want to have their own history.”

“As someone who collects records and books and furniture, it was really exciting to introduce collecting into my art practice, and leaving the studio, and going to bookstores, and sitting on the floor and just looking through things..” he says. “Some days are like, ‘Today is just a materials day,’ and I’ll spend the day sitting on the floor of the Strand bookstore in New York, going through things.”

“It was really helpful to open up what my practice could be and introduce scavenging for things and finding new materials,” he adds. “So much more fun to find a new book than to go and buy a new tube of paint.”

Initially, Craven did face a minor dilemma regarding his re-use of vintage materials — but over time, he has managed to find source material that not only falls in with his aesthetic principles but is relatively sustainable as well. Much of this has to do with changing technologies. For the past five years, Craven has been using primarily textbooks from the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s, as the closing of schools and shift towards digital classrooms have rendered old textbooks effectively useless.

“I didn’t even really think about it when I first started it — but as technology’s changed, these books are disappearing. They’re not even used for teaching. They’re not novels that can be used for entertainment, and most of all, they’re full of information that’s not even accurate,” he says. “All these Western-centric narratives: almost every English history book printed from the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s came from one manufacturer in London. They’re the ones writing history, and we’re all observing it as truth, and that’s been a part of the work.”

“It’s a dying medium,” he continues. “These are beautiful images out of these old beautiful books that are never going to be seen anywhere, so I got to the point where I was like, ‘I’m actually preserving these things in some ways, and showing people things they’re not going to see’ — or just having it be real, as opposed to on a tablet, or on a laptop… When you see the work in person, you can tell that it’s on old paper and old books, and I’ve kind of somehow crossed the line where you realize that these books are going to dumpsters; they’re going to landfills; they’re going to be destroyed; they’re never going to be used again.”

For Craven, this realization comes as a bit of a relief, and adds a meta dimension of timeliness to his already richly layered conceptual framework.

“I like history; at the same time, I’m very much trying to make work from 2015 and speaking about these kinds of things,” he says. “[It is important] to have my work speak to the fact that all these materials are coming from something that’s just slowly disintegrating from our conscience, with most of them being from textbooks that educate. That’s the first wave… kids are only going to [continue] using iPads and laptops, and they won’t carry around a backpack full of books.”

– Matthew Craven

Touching on The Universality of All Things

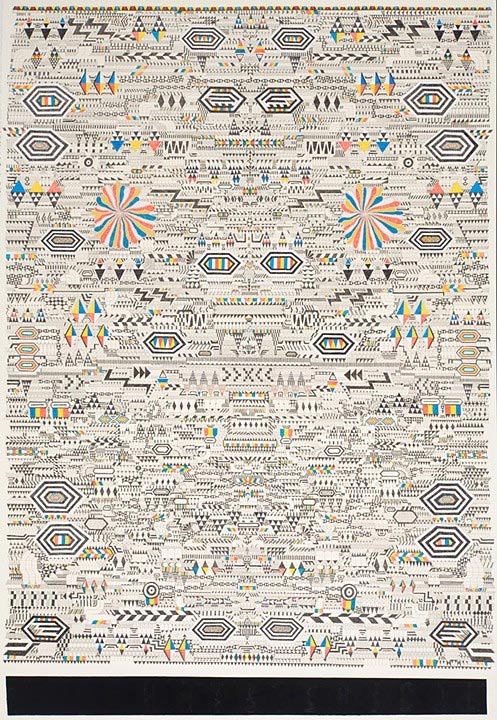

“It became this obsession that kind of ties back to all aspects of my life. It became about finding images of hand-made things, finding patterns that came from different civilizations, and most importantly, ‘Why do people create things? Why, as a kid, was I compelled to draw on everything and kind of decorate things?'” questions Craven.

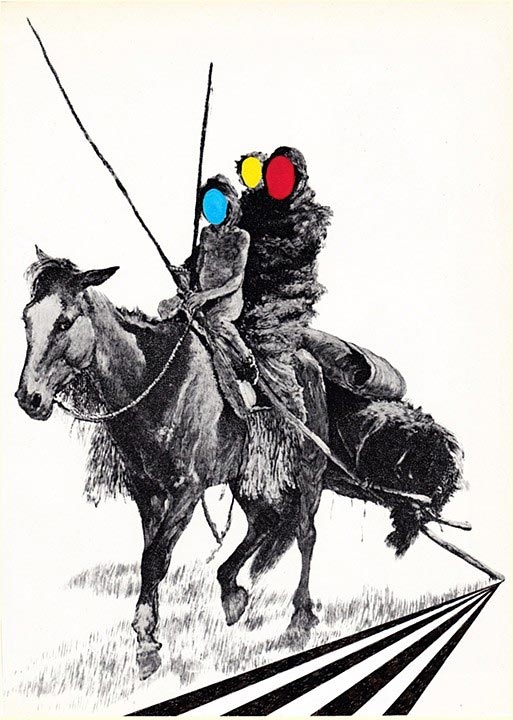

Diverse histories belonging to numerous cultures and populations are found throughout Craven’s work, and perhaps what fascinates him most is how disparate civilizations — many of which lived thousands of miles apart, and at different times — often had similar ideas. Yet Craven is an American Caucasian male, and as such, naturally faces judgments about making ethnically-sourced work. Over the years, he has received enough skeptical feedback that he realizes his work can trigger some viewers in ways that he does not intend, and in fact, finds rather disheartening.

Diverse histories belonging to numerous cultures and populations are found throughout Craven’s work, and perhaps what fascinates him most is how disparate civilizations — many of which lived thousands of miles apart, and at different times — often had similar ideas. Yet Craven is an American Caucasian male, and as such, naturally faces judgments about making ethnically-sourced work. Over the years, he has received enough skeptical feedback that he realizes his work can trigger some viewers in ways that he does not intend, and in fact, finds rather disheartening.

“People can read into the work how they want to — of me appropriating different cultures and different times and different aesthetics… I’m hoping people see it and they feel unified with humanity, and not segregated,” Craven states hopefully. “Some people see what I do and they get confused about my intentions as a white male artist talking about history, and it’s really sad sometimes, when I’m like, ‘I’m talking about humanity, and people.'”

There is a sense of meta-narrative in Craven’s works, which are rooted in history both conventional and “alternate” — but its wider view seems to possess sci-fi elements as well. Such an all-encompassing outwards stretching of time speaks to the artist’s interest that human beings — whether in the past, present, or future — have always, and will always, share a number of commonalities.

“You look down from outerspace, and we’re all the same, but we’ve made all these lines to separate ourselves from other people and cultures and we’ve created different languages even though we live right next to people,” states Craven. “That’s why I like the idea of just letting these images speak for themselves…”

Nowhere in Craven’s work will text be found, and the choice is very much intentional. His images are meant to stand alone, and the artist leaves subtle contextual clues only through his statements, the titles, and how the collaged elements are composed and juxtaposed with one another.

“I’m most drawn to patterns, not by what the culture is, but I’m most drawn to it when I kind of see it reappearing in different groups. A lot of times, people will be like, ‘Oh, that’s a Navajo pattern’ — but that’s also a pattern that was used in Ancient Egypt, and it’s also a pattern that was used by the Assyrians,” Craven explains, stressing that “finding universal patterns” is what he really likes about the process.

To the untrained eye, certain base elements of Craven’s works may look “tribal” or “appropriated”, but it takes someone who is a collector — who is truly fascinated by ancient cultures and has seen a wide cross-section of their collective output — to actually be able to gather and synthesize the commonalities in an accurate way.

And all of this research and pattern discernment basically comes down to one main thing: what interests Craven is and has always been the bigger story: the humbling universal story. It’s what pulled him away from abstract painting, and it’s what continues to drive him to unearthing new discoveries.

“Most of the cultures and work I’m using: they didn’t have their modern understanding of who they were and where they were. To me, we still don’t, but people act like we do or act like it isn’t a big deal, but that’s a common connection that I try to get across through my work: a little more mystical, a little more giving it up to the idea that this is all bigger than us,” Craven admits with great honesty. “Without being heavy-handed, I don’t make work about gestures or things about modern life. I really am trying to speak to very big concepts. It’s just the things that I lay in bed and I love talking to other people about.”

“I want people to stop and think how we got here. I’m not saying it was better before; I love living in the modern world — but to me, it’s fascinating that we went from there to here,” he continues candidly. “And I think it’s so easy to forget that there was this millions of years of human evolution to get us to this point, and it’s bigger than all of us.

“To me, it’s humbling. The subject matter is humbling. I like to feel small in a big universe. I know that scares some people. Some people don’t like to think about that. I feel inspired when I feel how big everything is; how long it’s been here.”

Ω

Select Works (from Newest to Oldest)

[…] http://www.redefinemag.com/2015/matthew-craven-artist-interview-existential-pattern-history-anthropo… […]