Some artists are prolific, churning out project after project at a speed that leaves onlookers wondering about their superhuman pace. Some have a much slower process — painstaking in intricate detail — and Eric Beltz is one of the latter.

A drawing teacher at University of Santa Barbara, Beltz is a master renderer, and his medium is pencil. His large-scale works take numerous months to create, and are crammed with dizzying details and meta-narratives. Steeped in naturalistic landscapes and historically significant symbols, each scene he creates not only reflects Beltz’s deeper life interests of synthesizing data, but his struggles with the slow pace of his art practice, as well.

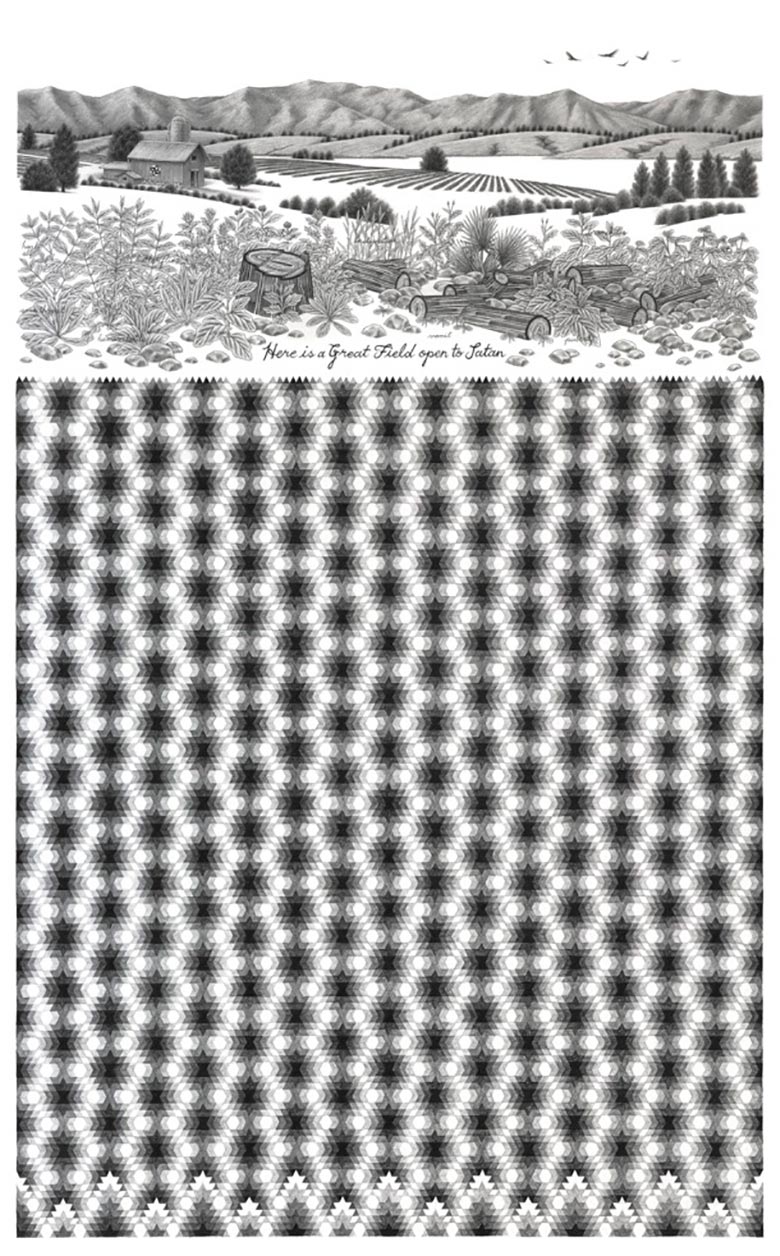

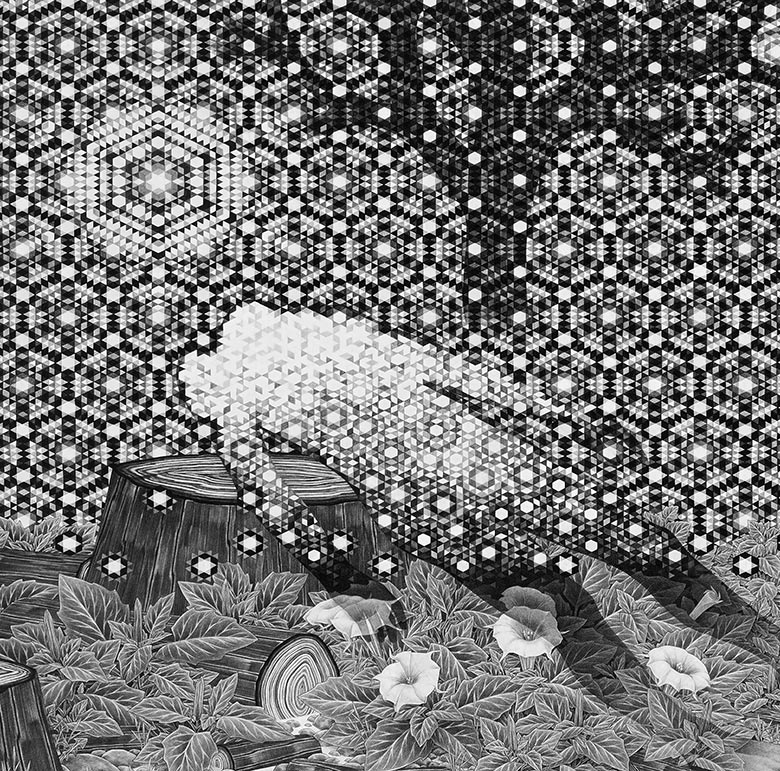

Here Is A Great Field Open To Satan, 2014

Peering Beneath the Fabric of the Universe

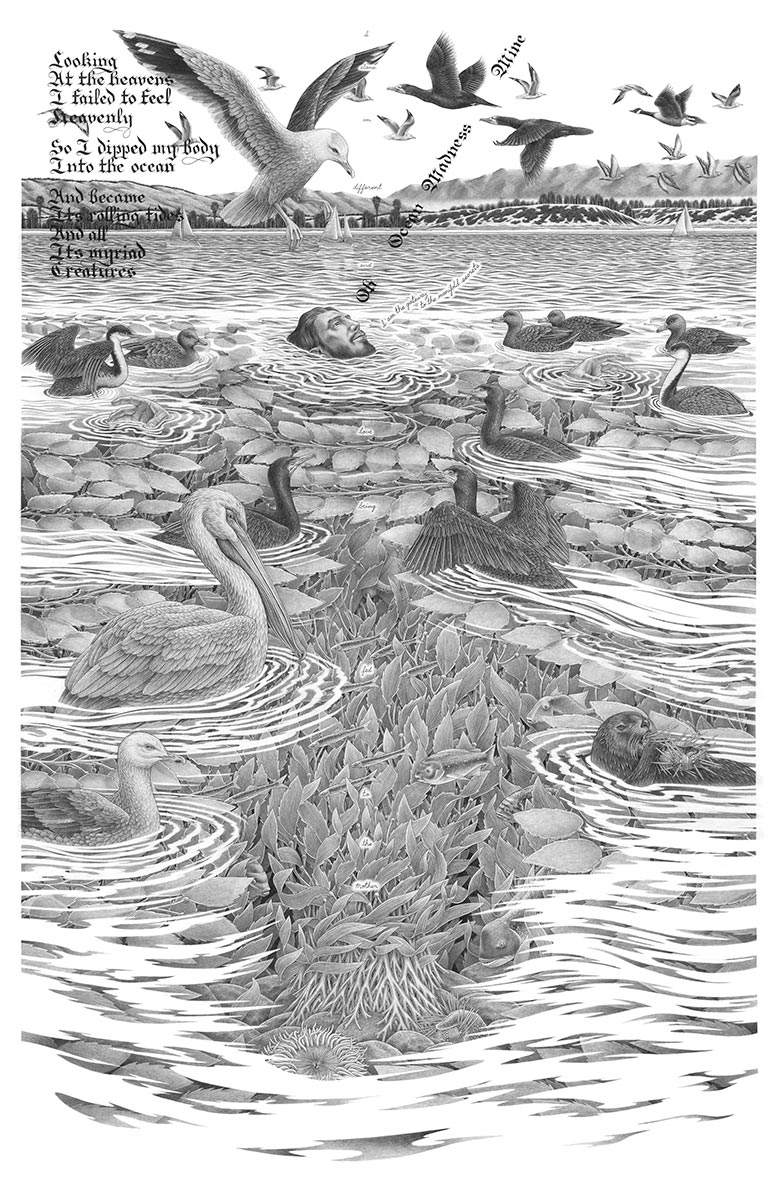

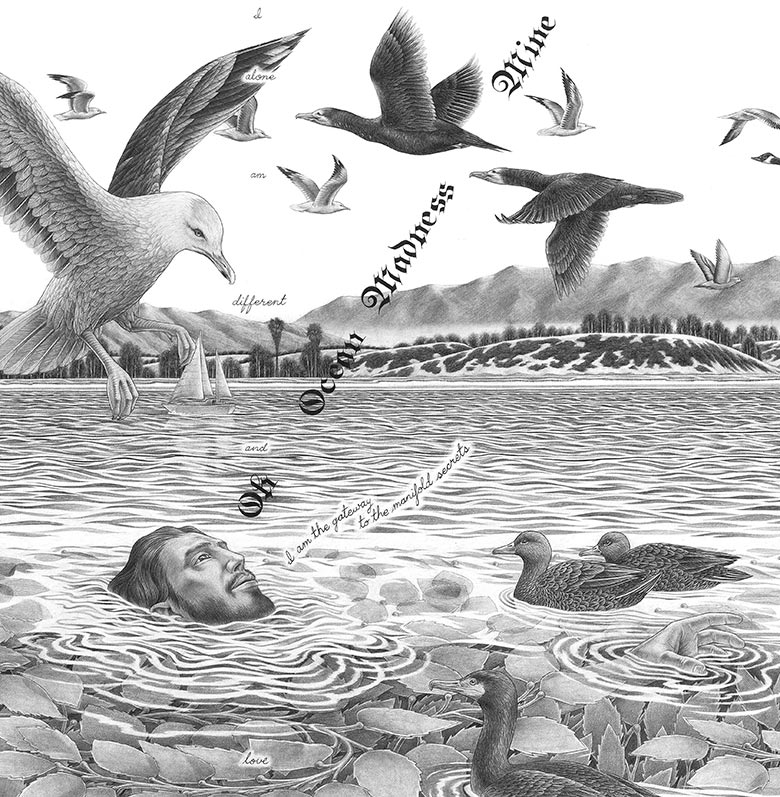

Just about everything visible in Beltz’s works is the result of hours of research, labor, and philosophical contemplation. He is lucky to finish a few large drawings a year — and it is perhaps due to this that much of his work, both ostensibly and inherently, seems to deal with time. Also present is the topic of transcendence, which Beltz admits he has been seeking since childhood. Though Beltz attended Presbyterian church with his grandparents as a young lad, children’s Sunday school never fulfilled his curiosities; he found himself hungering to attend adult church. When the time finally came, however, Beltz attests that “nothing happened”.

“I was expecting… some kind of manifest entity would talk to me or something, because that’s what stupid kids think, and it was just part of my impulse to contemplate spiritual concerns or divinity and things like that,” Beltz recalls. “That was sort of the earliest version of it — being disappointed in my church experience not having any sort of religiosity. It seemed more like a social thing. Everyone look at your neighbor, shake their hands, and afterwards we have doughnuts. Where’s the transcendence?”

It was in high school, after encountering psychedelics, that Beltz discovered his own personal meaning of religious experience and transcendence.

“That got me interested in the roots of not just religious experience, but the ecstatic experience, the transcendent experience, and looking behind things. Religion, mythology, shamanism, [and] psychedelic plants were the thing that gave people access to the divine realms, or the transcendent realms, or whatever,” Beltz says, offering an explanation for his focus on psychedelic plants and botany, as well as their connection to human beings and “the great body of whatever else is pulling everything together.”

“My interests are kind of bouncing back and forth, looking at my culture — how I was raised in a Christian culture, symbolism that comes out of that and being disappointed in it, and maybe wanting to make it my own fun again,” he continues.

“My interests are kind of bouncing back and forth, looking at my culture — how I was raised in a Christian culture, symbolism that comes out of that and being disappointed in it, and maybe wanting to make it my own fun again,” he continues.

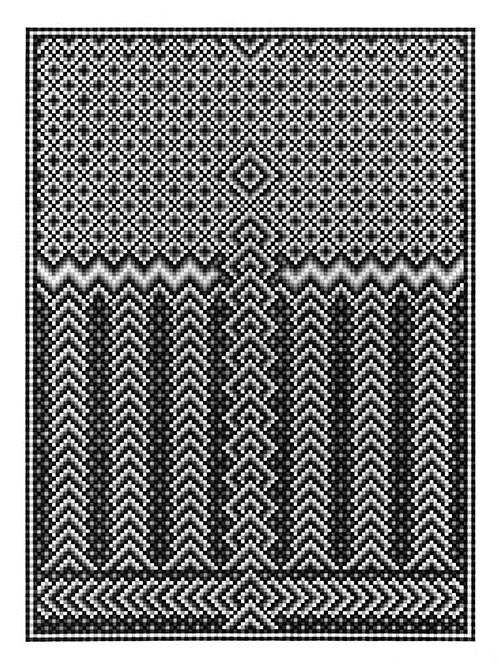

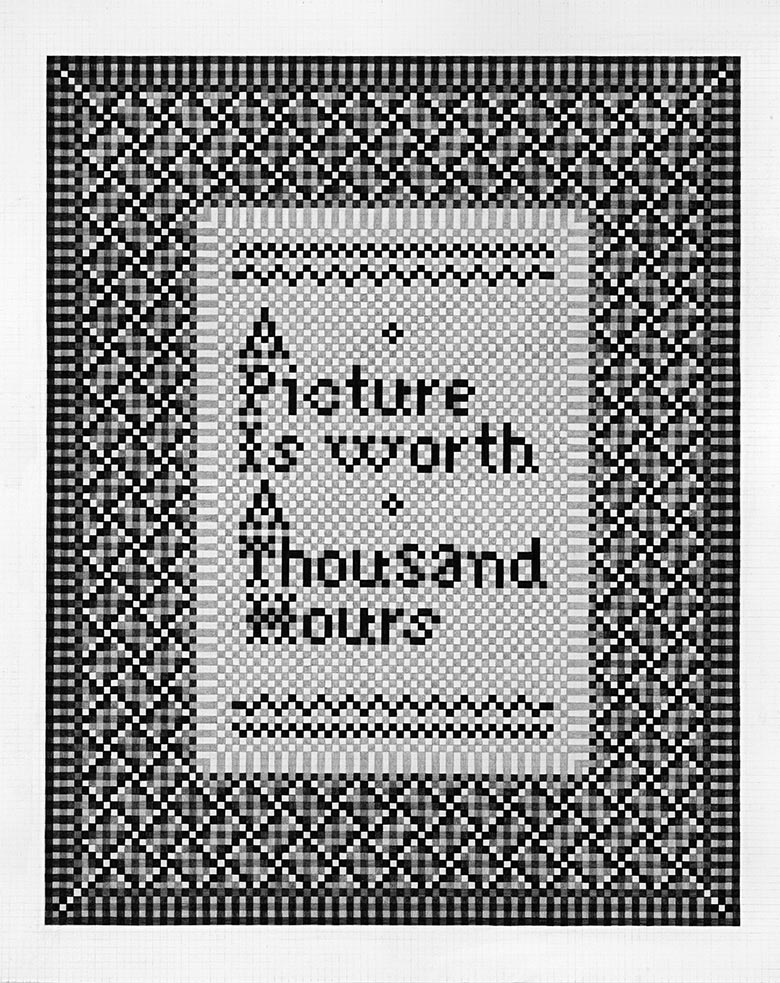

Although not necessarily limited to these two things, Beltz’s can be defined by the figurative and the geometric. His explorations of pattern are reminiscent of Americana-inspired textile weavings, whereas his narrative pieces seem like visual excerpts of Biblical passages which never were. His first patterned drawings, created in 2011, were directly inspired by an experience with DMT, or N,N-Dimethyltryptamine, which is an extremely potent but brief psychedelic substance.

“I was smoking [DMT],” he remembers. “I was in my backyard, and I had this sudden idea that if I blew on the vision I was looking at, it would break into pixels and spin, and I would see what was on the other side.”

Beltz did just that, and it seemed that he was able to peer into the underlying fabric of the universe, if only for a moment. For some time, he reproduced the intricacies of these DMT-inspired patterns, but even those are becoming so familiar their complexities no longer feel complex. As a personal challenge of sorts, his newest drawings attempt to break these long-established tendencies.

“When I look at my pattern stuff now… I can see the whole thing all at once. And when I see other people’s pattern drawings, and I see that also. To me, that’s the past. I want to see what the next step is. In some cases, I think pattern can be easy to do, and sort of safe…” admits Beltz.

“What really helped to motivate me was to see Nathan [Hayden]‘s wall drawing at a CB1 show,” he says, recalling a large, floor-to-ceiling painting made by the fellow Santa Barbara artist. “That took an amazing amount of confidence to do, because it was risky. And it’s a simple pattern that he allows himself to make some deviations from, but he couldn’t have really foreseen what it would have turned into, and I haven’t seen him do a pattern like that that’s been that amazing or that ambitious or that ballsy.”

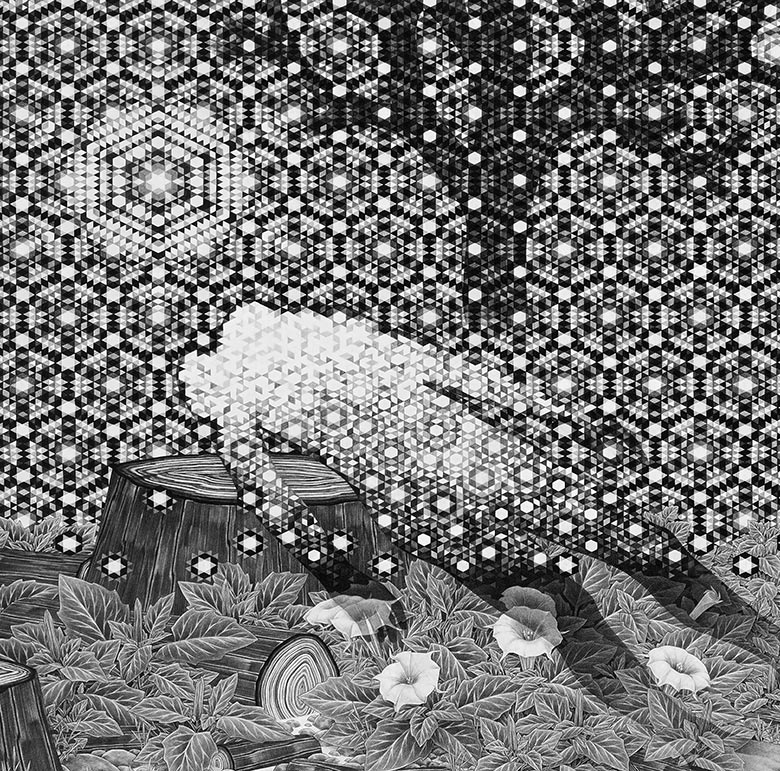

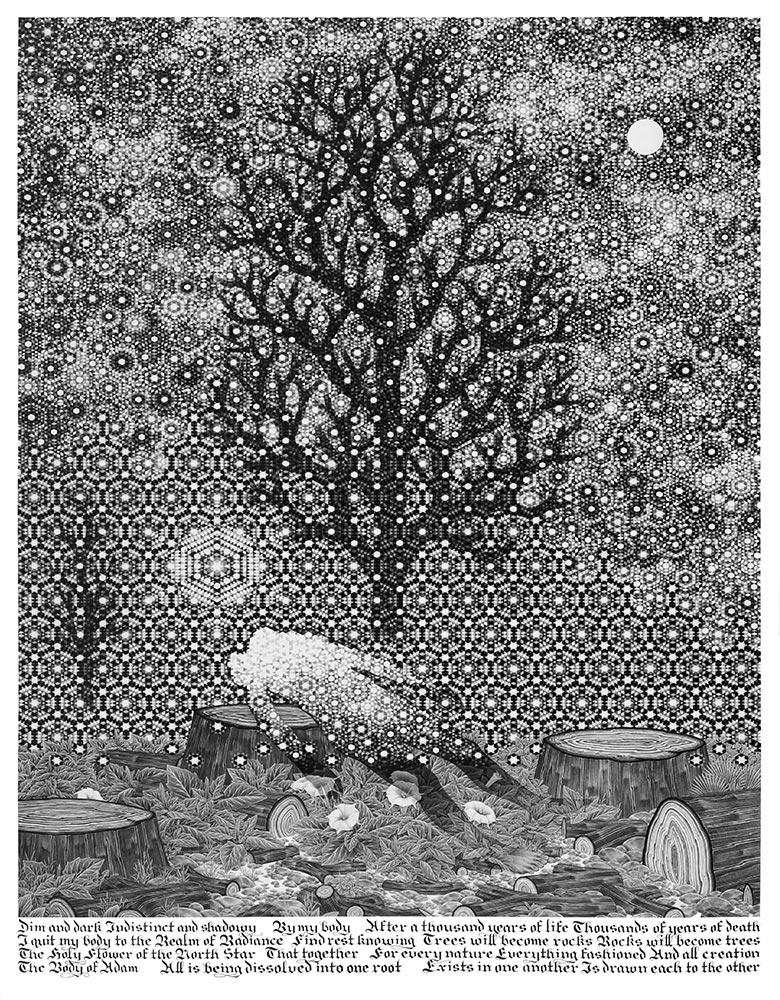

Body of Adam, 2016 (Detail)

One of Beltz’s most recent pieces, entitled Body of Adam, blends his figurative and patterned works, but there are deviations; its ornately patterned sky doesn’t become stuck in old grid-based habits, and are much less predictable. Beltz chose to “move the elements around a little bit so that they’re less regular — so there’s a regularity but there’s also a little bit of a distortion.”

Beneath the studded sky is the narrative itself, which is inspired by an apocryphal gospel, which are extra stories from Biblical times that were not included in the final book. According to Beltz, the body of Adam was kept in a cave called the Cave of Treasures until Noah’s son, Shem, saw a vision. He was to take the body of Adam and follow an ox, and where the ox ended up, he was to plant the body of Adam into the Earth, so that the city of Jerusalem could spring forth from his burial mound.

The story is an origin myth for the city of Jerusalem, and Beltz is quick to link it to other cultures and places.

“Most cultures, rolling back in time… had this idea where they came from the place where they are,” he explains, “and their name for themselves is just “The People”. We call the Navajo Navajo; they call themselves Diné; what’s Diné mean? It means people.”

“It’s that sort of idea of origin myths — that people look at themselves as coming from the place that they’re in, but sprouting from the ground kind of thing,” he continues. “So that’s that image from the apocryphal gospels, and I’m trying to use that image and bring it up in a new way.”

Though symbolically representative of Jerusalem, Body of Adam is in fact set in certain landscapes that Beltz finds himself drawn to time and time again, such as woodlots and gardens. Located within this woodlot, where certain planted trees have been chopped down, the souls of other trees are emanating with a glow, as though they’re in the process of transforming into something else. Again, transformation is central to the theme of this piece, and it is also represented by a semi-transparent ghostly figure, seen front and center. Surrounding this figure, Beltz gives a playful nod towards psychedelic leaves, consisting mostly of Datura.

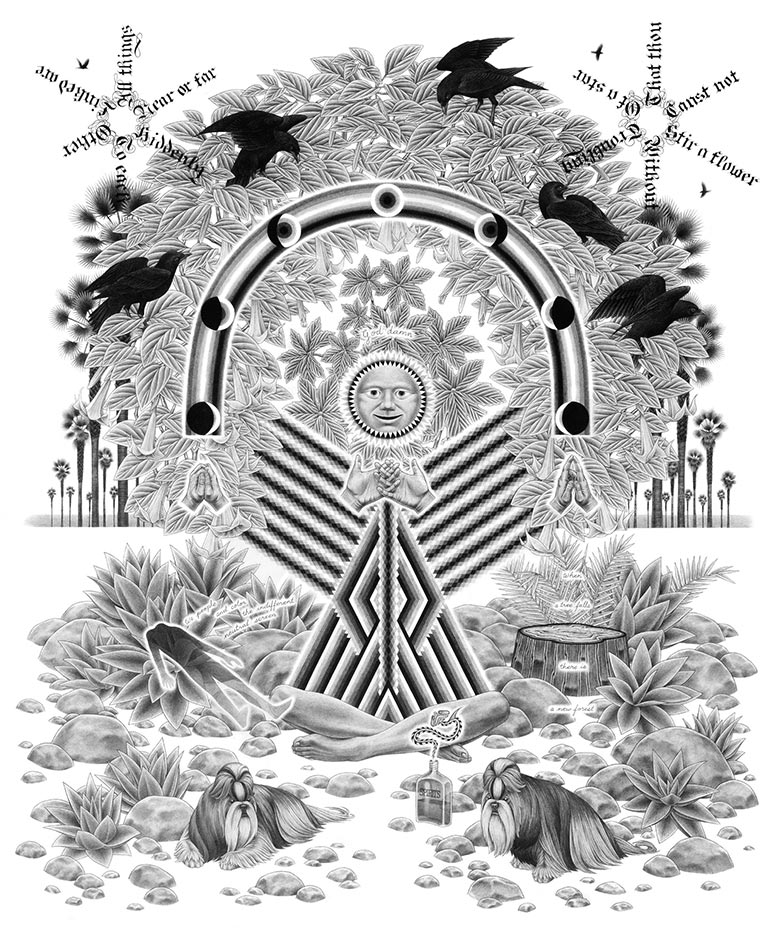

Buddha Zodiac, 2012

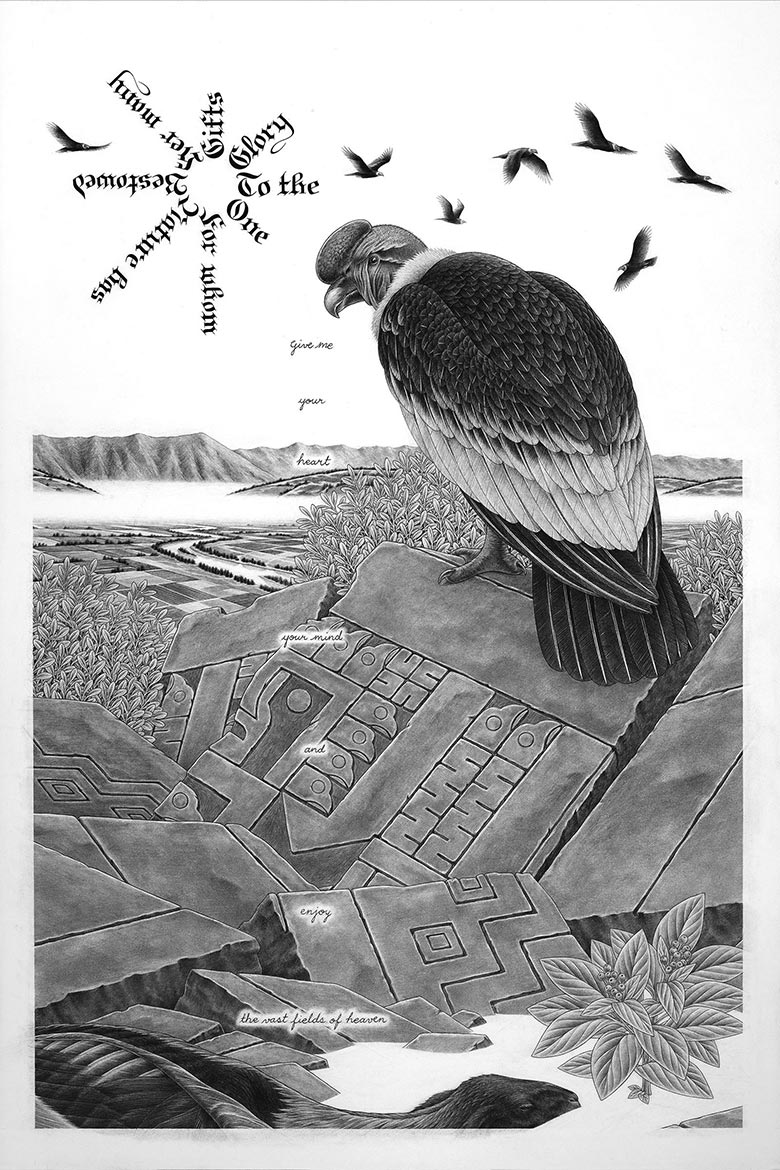

Andean Condor

Recontextualizing Symbols & Signs

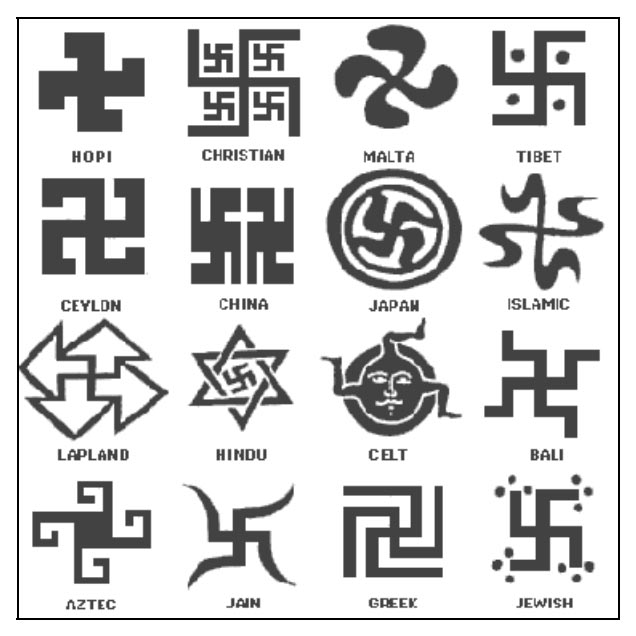

Beltz is a voracious reader who is fascinated by mythology and the origins of religious ideas. Central to his art practice is synthesizing ideas and themes he finds across various societies, and many of the commonalities he unearths can be represented by symbols. Take, for instance, his deep-rooted fascination with swastikas, which have become controversial due to the Nazis. But regardless of what initial triggers the symbol may set off now, Beltz remains enamored with it because it has appeared in numerous cultures around the globe — and to him, it holds much deeper significance.

“To me, it’s sort of tied to this ancient lineage of, maybe, creative practice, like turning an idea into an image. It’s one of the earliest symbols; that was one of the first things that humans came up with to make sense of something, and then it’s everywhere,” says Beltz.

In an interview with Emma Saperstein of The Harold J. Miossi Art Gallery in San Luis Obispo, Beltz recounts his first experience swastikas, during an Anthropology class on comparative iconography and symbolism. “[Professor Armand Labbé] introduced me to the Hopi ‘swastika’ (rolling logs, whirling logs) which is just a square with each side extended past the corner joint. He talked about the center element as representing origin and the arms representing emergence, growth, and movement.”

“This basic interpretation he then wove into larger metaphors regarding the sacred directions, the sun and moon, and the stages of human development over a lifetime,” Beltz continues. “That is, the symbol was fitted into a cultural context in this case the Hopi, but he also related their myths to cross-cultural examples to broaden the implications.”

Beltz has an art studio located beneath a set of bleachers on the UC Santa Barbara campus, and a collection of swastikas can be found throughout it — from a lazy susan shaped like whirling logs, and penciled illustrations mounted on the wall, down to the ring he wears on his finger, which was an early tourist souvenir.

“This is an early trade silver ring that you would have bought if you took a train from Missouri to Arizona or New Mexico in the ’20s and ’30s,” Beltz details. “These Italian entrepreneurs set up trade posts at hotels and at train stops, and they got the Navajo Indians and employed them to make these things.”

Beltz states that ancient Egypt was the first culture to use the swastika, but that it eventually gained meaning all over the world. In J.E. Cirlot’s A Dictionary of Symbols, Cirlot comments on its universality, saying, “The graphic symbol is to be found in almost every ancient and primitive cult all over the world — in Christian catacombs, in Britain, Ireland, Mycenae and Gascony; among the Etruscans, the Hindus, the Celts and the Germanic peoples; in central Asia as well as in pre-Columbian America.”

Beltz states that ancient Egypt was the first culture to use the swastika, but that it eventually gained meaning all over the world. In J.E. Cirlot’s A Dictionary of Symbols, Cirlot comments on its universality, saying, “The graphic symbol is to be found in almost every ancient and primitive cult all over the world — in Christian catacombs, in Britain, Ireland, Mycenae and Gascony; among the Etruscans, the Hindus, the Celts and the Germanic peoples; in central Asia as well as in pre-Columbian America.”

But perhaps it is the more longstanding usage of the symbol that remains more important and fascinating for Beltz. He cites its use in East Asia, and hypothesizes as to why the symbol might still hold different meanings in cultures that are not Western.

“With Asian culture, in general, there’s a totally different relationship with the swastika. I can imagine it being something like this: if you’re a part of a culture that has been actively using a swastika for, since time immemorial, and then these asshole Germans come along and are like, “Oh, that’s our symbol now,” and you’re like, ‘No, you lost anyway, so…’ We’re just going to keep using it,'” he hypothesizes.

In America, the use of the symbol is much more casual and less long-standing; Beltz cites postcards he’s purchased off of eBay that use it as a good luck symbol, printed with words like, “I love you!” and “Happy birthday, aunt!”

“It’s like a smiley face, basically,” he adds. “Put a smiley face on it, and it means good luck… until it didn’t.”

The fact that the symbol no longer holds such levity in American culture does, Beltz admits, make some people uncomfortable — but he maintains that most people “don’t automatically assume”, and that “they’ll kind of make up an excuse for me.”

“For me, it’s just a very beautiful symbol, and because of its Nazi symbolism, or reference, or whatever, it’s got a pretty heavy charge to it, and that resonates bigger or smaller depending on each person’s relationship to Nazi stuff,” says Beltz, who personally does have a grandfather who was a WWII Navy veteran. “But it’s just a beautiful symbol, to me… it’s a thing that I think gives you a connection to deep humanity, and the fact that this thing happened that is undeniably horrible doesn’t reboot our human history. It’s a blip.”

Santa Barbara Swastika, 2013

Recommended Reading from Eric Beltz

Steppenwolf by Hermann Hesse

The 26 pages within this book titled “Treatise On The Steppenwolf” bowled me over when I first read it, and I return to it often. This section is a book within a book within a book and is itself layered alternately with biting German angst and Indian spiritual philosophy. His language is profoundly vivid when describing the self as “a manifold world, a constellated heaven, a chaos of forms, of states and stages, of inheritances and potentialities”.

The Lost Books of The Bible and The Forgotten Books of Eden

This book inspired in me an interest in the Apocryphal Gospels. I found it at an estate sale in Santa Barbara surround by books on aliens, Rosicrucians, psychic phenomena, and eastern religion. The idea I extracted was that these were the richer, more fantastic, and less dogmatic stories featuring familiar characters such as Adam and Eve, Noah, and Jesus.

Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu

Lao Tzu’s subtle leveling of transcendence and manifestation as shades of difference, as equal objects of reflection is a palliative to the spiritual crisis I find myself in sometimes. His writing is calming, insightful, and playful. My favorite line from the D. C. Lau translation is: “The great square has no corners.”

Plants of the Gods by Richard Evans Schultes

I think Schultes was the perfect man to be the vessel for data on the cultures that traditionally embraced the use of hallucinogenic plants for positive social effect at a time when American culture was on the verge of the ‘psychedelic era’. This introductory overview covers just about everything you need to know about the major potent plants and places them all in a carefully described cultural context.

Exile and the Kingdom by Albert Camus

This 1957 collection of short stories surprised me with how contemporary they feltm particularly “Jonas, or The Artist at Work”, where Camus shows how the artist can become the least important part of their own careers especially if their work succeeds in exciting collectors and critics. This felt very much like what happens to artists at art fairs.

Sonnets by Shakespeare

I was drawn to the Sonnets by a story Jim Harrision told about how he would criticize his writing students: “You might look in the mirror and say, ‘I’m getting old,’ but Shakespeare would say, ‘Devouring time bunt thou the lion’s paws.’ My favorite Sonnet is number 29, which I read as evocative of the internal process I experience sometimes in dark moments of doubt and envy, and the uplifting forces that rescue me from that abyss.

The Savage Sword of Conan

Some of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories are fantastic with dripping, oozing language: “Then there was murder, grim and appalling.” The art of this series of comics from the 1970s is especially good when done by John Buscema who co-wrote a great book I use all the time in teaching drawing: How To Draw Comics The Marvel Way.

Guardians of the Lifestream by Armand Labbé

Armand was my mentor in college at Cal State Fullerton. His writings on pre-Columbian shamanic art and culture, and comparative symbolism are insightful, systematic, and most importantly create an opportunity for a real awakening through understanding. He demonstrated courage and independence in everything he did. I always have a copy of this book in my studio.

Finding Torture in Indulgence

But regardless of whether onlookers simply give Beltz the benefit of the doubt, or whether taking the path of least resistance is simply easier for them — one thing that is clear is that Beltz really is just naturally drawn to controversial symbols.

“It’s like poison oak — or other taboo things — or just things I tend to gravitate towards,” he says.

Some artists embrace dark themes as a way of processing information and working out personal demons. Beltz, who believes himself to be generally quite content in life, does not see his work as a means to catharsis. In fact, that common tendency seems almost too easy an explanation for his magnetization towards darker themes.

“It’s more of an indulgence in stuff that I think is awesome,” he explains. “It’s not a therapy for me. If it was therapy, I’m doing it fucking backwards, because it makes it worse.”

“With the pattern stuff, my wife’s like, ‘You can’t do those pattern pieces anymore; they make you nuts,'” Beltz continues. “But I think — and most of my work is sort of torture to make, because I’m trapped. My work’s about nature, but I see the seasons pass me by, and I’m still drawing a leaf that has no season to it. It’s just the idea of a leaf. And to me, there’s sort of something sad about that process, because the world is changing, but I’m freezing it, in a way. In fact, freezing time is a really core problem for me, as an artist who works in images of stuff.”

“And that’s partly why — most of my figures, if not all of my figures, are frozen in a transcendent moment –” Beltz explains. ” — because the idea of capturing fake motion in a figure is just always something that I’ve wanted to avoid. Because if you look at all my figures, they’re static. They’re frozen. They’re captured by something.”

Regardless of what Beltz freezes in time, though, there is an also an element of movement — of action stirring underneath the surface.

“With the Jesus drawing, the ocean has a little Bridget Riley wiggly stuff — or with my pattern pieces, I try to create a pattern that bounces around in your eyes, so there’s actual motion that you experience when you’re looking at the image, even though it’s frozen,” he explains.

And in that sense, maybe Beltz is working out something about his place in life. His artwork is almost like a parallel mirror, through which his life experiences are filtered down. Yes, he might be stuck in a studio, frozen in time, drawing a leaf while watching the seasons go by — and yes, his works may continue to deal with similar themes of transcendence and taboos and nature and cultures… but there are changes, within Beltz himself and the art he creates. All of it is speeding it up, too… albeit slowly.

When Jesus Swims He Becomes The Ocean, 2014-2015

When Jesus Swims He Becomes The Ocean (Detail), 2014-2015

Chromatose, 2014

Elementary Forces 6, 2013

Ω