Influencing Generations to Come

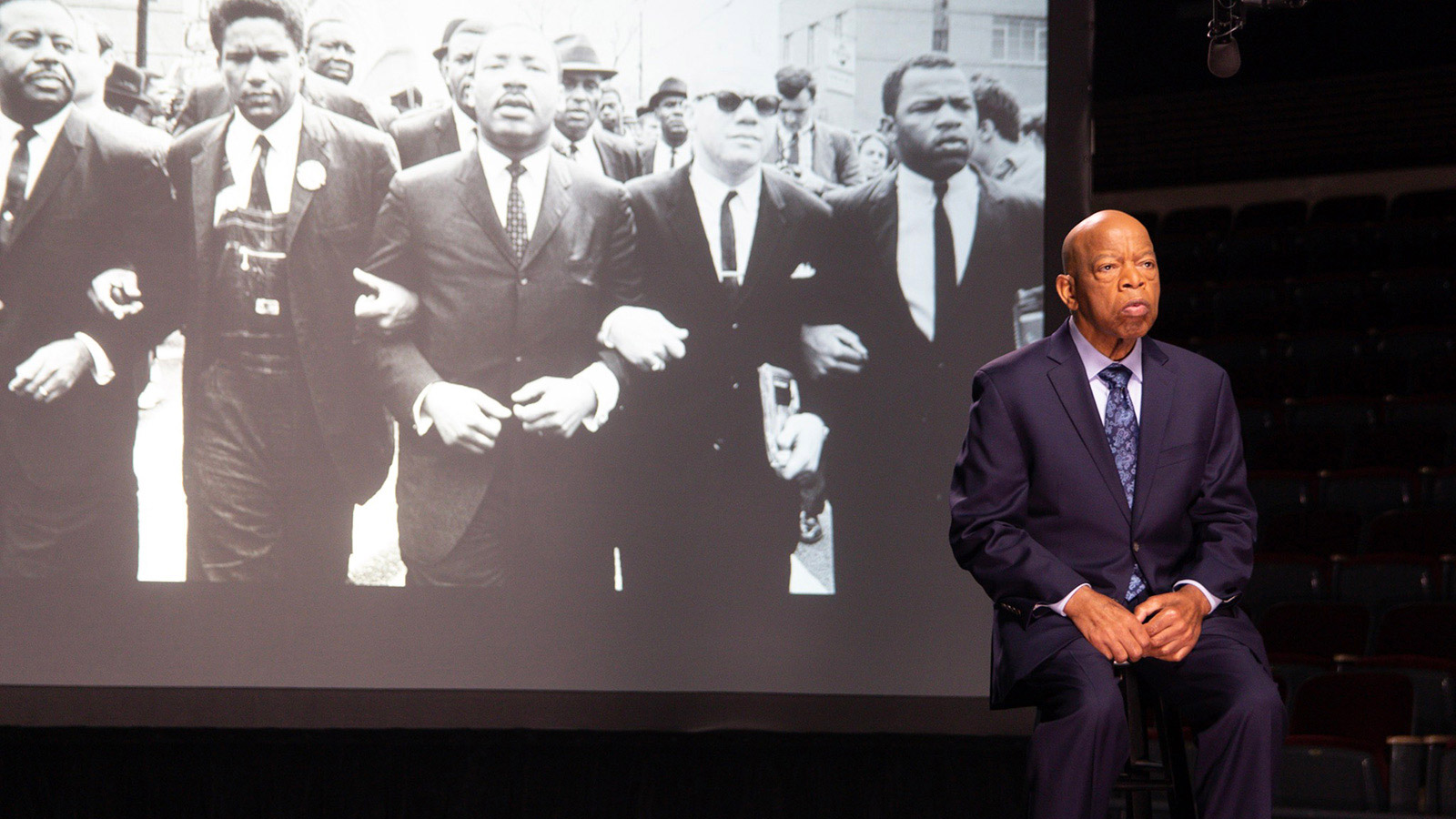

John Lewis’s impressive legislative work makes him unique among sixties civil rights activists. He is someone who has both marched in the streets and drafted laws in the halls of power. Sometimes these two roles collide, as when he led a sit-in on the House floor in 2016 to call attention to the need for new gun regulations after the mass shooting at Pulse nightclub in Orlando.

“He does understand that the most powerful nonviolent tool for change is the vote, and if you want to protect the vote, and you’ve also done the marching in the streets, then the best way to really make sure those systems work is to be a legislator,” explains Alexander.

The rights Lewis fought for in the sixties are currently under attack in many states. Referring to voter ID laws, purging of voter rolls, and administrative decisions that shrink the number of polling places in minority neighborhoods, Lewis says in the film, “There are forces today trying to take us back to another time.”

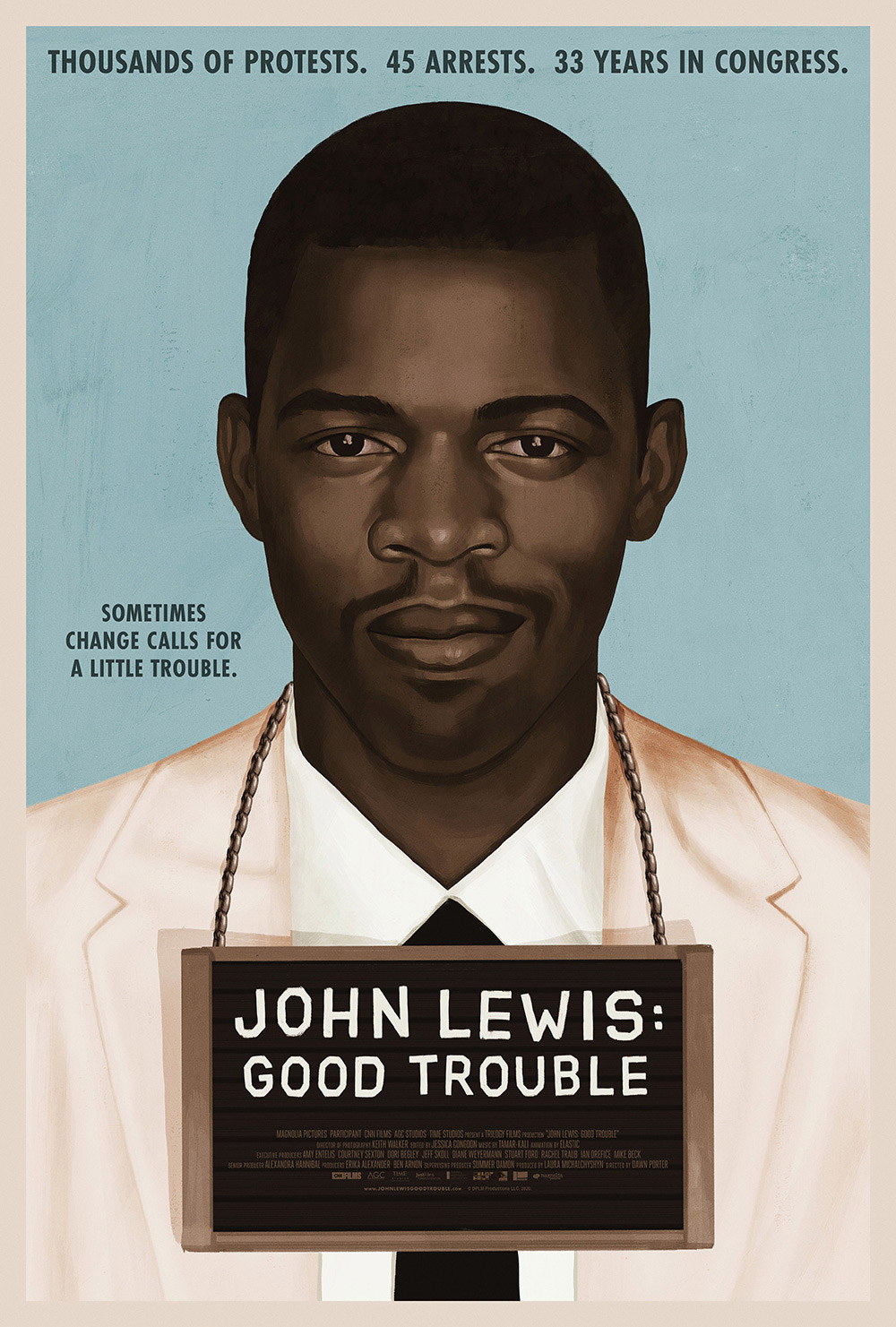

Good Trouble illuminates Lewis’s influence on a generation of activists, and awestruck testimonials from New York Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and New Jersey Senator Cory Booker reveal just how much he’s expanded our definition of what a politician can be. Ostensibly, Lewis has succeeded in the realm of politics without being corrupted by it. He has the tangible achievements of an incrementalist and the moral backbone of a radical.

Creating Meaningful Civil Rights Legislation

Nonetheless, Good Trouble shows that Lewis’s shift to party politics was never inevitable. Lewis’s first foray into congressional politics didn’t seem to augur a long and fruitful career. “Not everybody who agitates against the government can or wants to enter it and actually be a legislator,” Alexander acknowledges.

When Lewis first ran for a House seat in Georgia in the ‘80s, his primary opponent was Julian Bond, his longtime friend and fellow civil rights activist. The race between the two of them became contentious, despite a longstanding friendship. At one point, in a now-dated jab, Lewis demanded that Bond take a drug test. This is perhaps the only moment in Good Trouble where Lewis acts in a way that cynical people expect of politicians. Still, Lewis’s congressional legacy has been far more about manifesting a progressive vision for the country than mudslinging his opponents. There’s a prophetic shot in Good Trouble of Lewis speaking at the 1963 March on Washington, with a furrowed brow and preacher-like cadence. In a sea of faces, one homemade sign sticks out. It says, in all caps, “Meaningful civil rights legislation,” perfectly encapsulating the future intersection of Lewis’s dual roles as activist and legislator.

“White people created a system of laws and policies and financial networks to control and oppress African-Americans. And the only way to destroy it, to the core, is to bring about systemic change. And that’s by voting. And John Lewis knew that the vote was everything,” says Alexander.

The sit-ins, marches, and other pressure brought by Lewis and other activists culminated in the 1965 Voting Rights Act, arguably the most important piece of civil rights legislation of the 20th century. A key provision of the act, however, was struck down by the Supreme Court in the 2013 case Shelby County v Holder. Pre-Shelby, the Justice Department had the power to veto new election laws in states with a history of voting discrimination. After the Court’s 5-4 ruling, the Justice Department was essentially reduced to a defensive role just as new voting restrictions proliferated.

Empowering Voters to Press On

Good Trouble powerfully sandwiches ‘70s-era footage of Lewis registering rural black voters in the South with video of African-Americans waiting for hours at polling stations today. The film’s coverage of the 2018 gubernatorial race in Georgia—where Lewis campaigned for Stacey Abrams, who was aiming to be the first female black governor in history—is a case study in the shameless and near-authoritarian methods of modern voter suppression. Dystopian voiceovers from news organizations tell us that the office of Georgia’s secretary of state, Brian Kemp, purged millions from the voter rolls, largely people of color. Not coincidentally, Kemp was also Abrams’ opponent in the race and is the current governor of Georgia. As Lewis says somberly, while paging through The New York Times, “My greatest fear is that one day we may wake up and our democracy is gone. We cannot afford to let that happen. As long as I have breath in my body, I will do what I can.”

Nonetheless, Alexander looks back fondly on her experience campaigning with Massachusetts Representative Ayanna Pressley, Lewis, and Abrams. “That was really a masterclass in how to be young, gifted and black in the South in politics, with a master: John Lewis,” she says. “And you can see that they were ready; they were ready to emerge. There’s a new generation that’s got the blueprint, and they’re not playing.”

Good Trouble could not be more moving in showing viewers the charm and magnetism of John Lewis, still fiery and inspirational at 80. During a speech at a black church, he describes how he preached to his chickens as a kid. While they never said “Amen,” Lewis joked, they were still better listeners than some of his Republican colleagues. In an off-the-cuff moment, he tells his legislative assistant, totally deadpan, to wipe the sweat off his brow because he doesn’t want to blind anyone at the hearing that day. This seeming clash — the fact that Lewis is both riotously funny and incredibly serious about what matters — is captured by the viral video of him dancing to “Happy” by Pharrell Williams.

“They say don’t meet your heroes, they disappoint you — and he does not. He is unexpectedly pleasurable and beautiful,” Alexander sums up perfectly.

Yet Good Trouble does more than just show us that activists can also have a sense of humor. There’s a deeply moving sequence where Lewis’s two brothers, who radiate the same calm that he does, admit that they used to worry about his safety. In another scene, Lewis’s friend describes how Lewis met his wife, the smart and politically minded Lillian Miles. According to Alexander, to see Lewis as a full person — a lover of art and chickens and a loving father and husband — can be politically important. To see him as fully human, as more than a secular saint, has profound implications.

“Because if we do, we see ourselves in him,” says Alexander. “We see that the blueprint that he left us is not outside of ourselves. He is a flesh and blood human and when they cracked his skull on the Edmund Pettus bridge, they saw red blood like everyone else had.”

While Good Trouble holds Lewis up as an inspirational figure, it doesn’t ignore his basic humanity. This fallibility only makes his sacrifices all the more profound.

Good Trouble Impact Campaign

In addition to highlighting the perennial importance of voting rights, the impact campaign around Good Trouble also does some activism of its own. Participant Media, working in collaboration with Magnolia Pictures, has an entire website devoted to mobilizing voters. The site contains information about voter suppression throughout the entire country, from Arizona to New Hampshire, but is especially focused on Georgia and North Carolina — two states that Lewis has a connection to which are known for their voting rights issues — and includes links where people can sponsor the mailing of voter registration cards to unregistered voters. Participant’s impact campaign couldn’t be more timely. The June 2020 primaries in Georgia srecently made national news for their long polling lines, finicky operating equipment, and difficulties with mail-in ballots. In response, the Atlanta Hawks pledged to turn their arena into a polling station.

“The ultimate goal of the impact campaign around the John Lewis feature is to amplify his core value, which was the power and the sanctity of the vote,” says Alexander. “The fact that we have so much gerrymandering and rules that have limited people in the worst ways since the fifties and sixties is unacceptable and untenable.”

You can screen the film online now via Northwest Film Forum.

Ω

[…] that included “six members of the Congressional Black Caucus, among them civil rights legend, Representative John Lewis […]