Since I Been Down uses the Hilltop neighborhood in Tacoma, Washington — infamous for gang violence in the ‘80s and ‘90s — as the backdrop for exposing how racism gets embedded into policies that masquerade as public safety measures. While the tough-on-crime policies of Presidents Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton are infamous, fewer know about Washington’s role in mass incarceration: in 1993, it became the first state to pass a three strikes law, and it is one of just sixteen states without parole.

“This film deals with people who have committed violent crime,” explains Sheppard. “It’s not even a question of, ‘Are they innocent?’ This is not a film about innocence. This is a film about what we do to our children, and what is justice.”

Sheppard’s years of teaching sociology classes in and outside of Washington prisons have been integral to her research. The film uses a rich variety of intimate interviews and archival materials, from newspaper clippings to grainy home video and photos of a teenager’s AK-47, to help evoke the complexities of a community in crisis.

“[My students] introduced me to their mothers, their fathers, their former peers who were in gangs who had gotten out of gangs,” she says. “So I went with this kind of legitimacy into the community, and that’s the reason I got this home footage. And I got it from their perspective; from their gaze — the kind of cinema vérité of throwing up a gang sign.”

Since I Been Down details how the government’s response to gang violence and the crack epidemic was rarely about preventing crime, let alone understanding its underlying causes. Instead, dehumanizing newspaper headlines conjured the threat of “thugs” and teenage criminals — or, as Hillary Clinton infamously put it, “superpredators.” After Tacoma received federal funding in 1989 for a task force to target gangs, the sphere of “suspicious” activity expanded profoundly. Interviewees describe the jailing of loiterers and no-warrant searches of houses. Detective John Ringer, who directed the task force, recalls that his job was ideal because he “didn’t have much supervision.”

One of the film’s subjects, Tonya Wilson, grew up in Tacoma’s Hilltop neighborhood and describes to REDEFINE the distrust this heightened policing created — including one particularly galling law enforcement tactic.

“They would take the littlest kids to the Dairy Queen, buy them whatever they want, and then get them to talk,” Wilson recalls. “They would be right there, right on the corner of 12th and Sheridan, and they would get these kids to tell on the people who were taking care of them.”

“Gangs are not the root cause. Drugs are not the root cause. These are public health issues,” says Sheppard, reflecting on the human cost and ultimate ineffectiveness of punitive policies. “Instead of going to the root cause, it was a pipeline to prison; a pipeline to punishment. I think of [Equal Justice Initiative founder] Bryan Stephenson, who says that the answer to poverty is not wealth; the answer to poverty is justice.”

Yet fervent fears about gang violence manifested in harsh and unjust laws. In 1994, Washington’s legislature applied the death penalty and life imprisonment to drive-by shootings. Kimonti Carter, one of the founders of T.E.A.C.H. and a notable figure of atonement, is serving a life sentence for his participation in a fatal drive-by shooting when he was eighteen. Carter received a sentence of 777 years in prison; a conviction of first-degree murder would’ve carried a sentence of twenty-seven years.

According to Sheppard, a toxic combination of harsh punishment and disinvestment in Tacoma’s Black community created a “non-negotiable pathway” to prison for many of Since I Been Down‘s subjects. In one scene in the film, prisoner Willie Nobles reflects on the irony that he and Carter, former rivals from opposite sides of town, now run the Black Prisoners’ Caucus together. The gang insignias and affiliations from that era have become irrelevant, but the lengthy sentences have stuck. Shots of barb-wire fences, pat-downs by prison guards, and somber lunch lines accompany a voice-over describing how incarcerated individuals are treated like cattle. Corrections officers won’t even make eye contact, Emilio Maturin says.

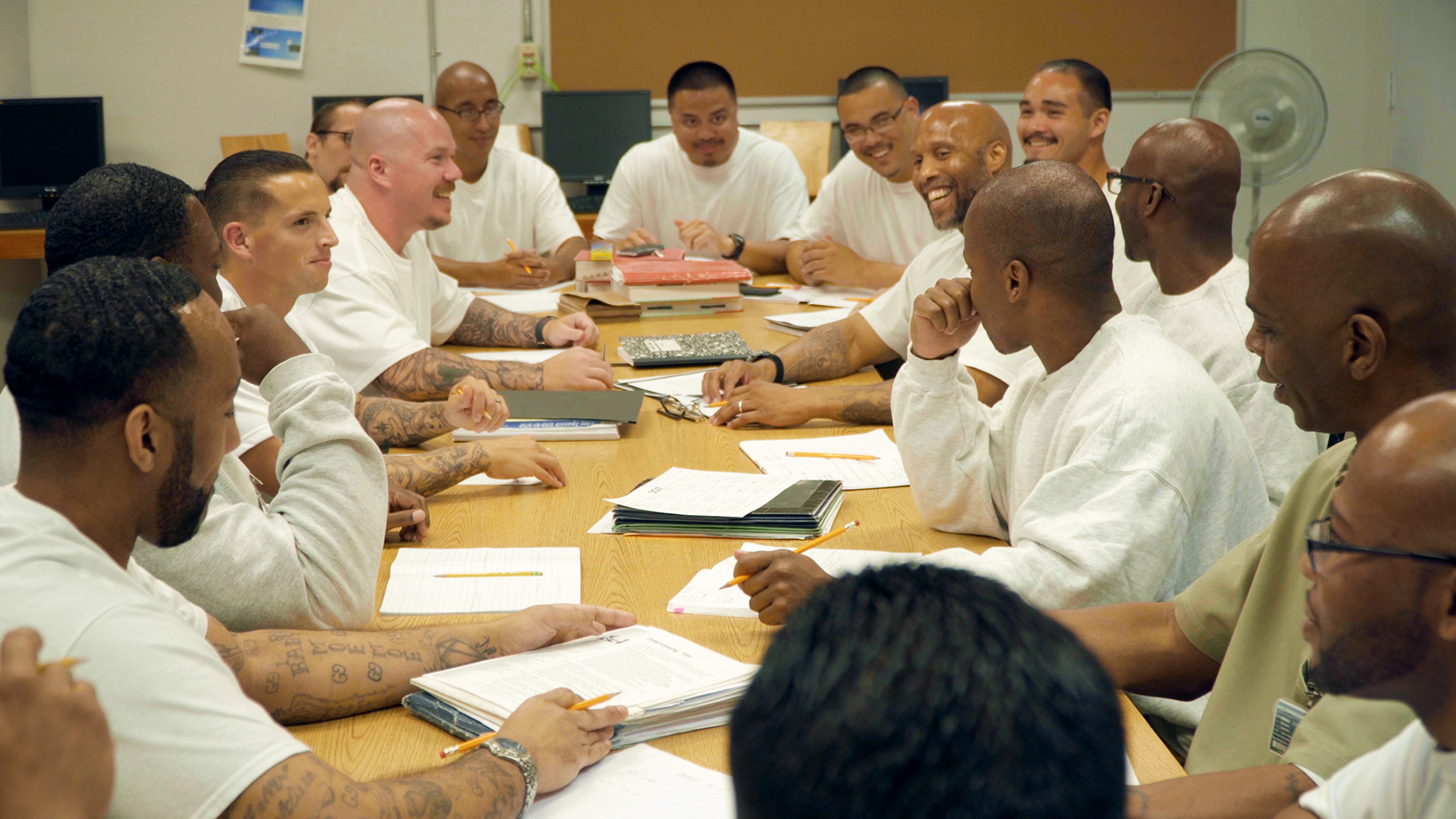

Within this environment seemingly designed to stifle personal growth, Carter has tried to reclaim dignity and agency. He was the president of the Black Prisoners’ Caucus at Clallam Bay Corrections Center, where he organized both intimate group workshops and summits on racial justice in packed auditoriums. The Black Prisoners’ Caucus was born out of the Black Power movement, anti-racism organizer Mary Flowers explains, and that DNA of empowerment and liberation is still with the program today, even as it has expanded to ten prisons throughout Washington. Through its educational program, T.E.A.C.H., prisoners design curriculum based on their life knowledge and lead classes on everything from algebra to Asian-American studies. It is a liberatory program, according to Sheppard.

“They started these classes for healing, transformation, and so that people could see themselves as human and could see the real practice of justice,” she says. “These classes start with your culture. And from there — finding out who you are… you do a class called Healthy Thinking, do a class on algebra, literature, a philosophy course on Immanuel Kant, all kinds of things.”

T.E.A.C.H.’s commitment to serving all prisoners also makes it unique. Other educational programs in Washington’s prisons prioritize those with less than seven years of a sentence remaining, despite the fact that determinate sentencing has lengthened prison stays. T.E.A.C.H.’s broad reach allows it to provide a normal classroom experience to those who have been deprived of normalcy.

“When I come up here to teach everyday, I have to check myself continually, because at times I feel free,” the soft-spoken instructor Demar Nelson reflects. “It does something for my soul… for us to be able to transcend this cage that we’re in, and to reach people, and to actually make a difference, it reminds me everyday that I have a chance. I don’t believe that the walls can change my potential and my purpose.”

Nelon’s statements articulate both the fundamental value of the program and what makes it heartbreaking; T.E.A.C.H. may be as authentic a simulation of freedom as prisoners will get while serving their time.

Since I Been Down powerfully portrays Carter’s redemption through his involvement in such programs. As his lawyer points out, there’s an inherent absurdity to sentencing an eighteen-year-old, who will inevitably grow and change, to an immutable sentence of life in prison. Carter, who even a corrections officer admitted had done more to improve race relations than even prison employees, is not a risk to society. Rather than a public safety measure, his sentence represents the state’s revenge — which not even the family of Corey Pittman, the man he killed, endorses. In one moving scene, a close friend of Pittman describes how forgiving Carter was necessary for her own process of healing, even though her grief over Pittman’s death endures. In response to Carter’s email asking for forgiveness, she replies, “I forgave you a long time ago.”

“The executive director of the program that I work for says that people in prison, whether perpetrator or victim, do not need to change,” Wilson says to REDEFINE. After spending nearly two decades in prison, despite asserting her innocence, Wilson now works as Reentry Outreach Coordinator with Freedom Project — an organization that supports healing connection and restorative communities both inside and outside prison. “It’s not about change; it’s about healing. We are already brilliant, gorgeous, great. But until you heal from whatever your trauma is, there’s no way to manifest that greatness because you don’t believe it for yourself.”

Since I Been Down marries a mission of personal transformation with one of structural change. It’s a quietly radical documentary that asks society to imagine what justice would look like for a community that has been neglected and criminalized for far too long. Programs like T.E.A.C.H. and the Black Prisoners’ Caucus work within the constraints of a broken prison system to allow prisoners to realize their own worth.

“What is justice? What comes to mind when we hear the word justice?” asks instructor Marco Rodriguez as he leads a T.E.A.C.H. class. After his students float words like “oppression” and “corruption,” Rodriguez reframes his initial question.

“Justice is related to all the bad things that have happened to us… so we go with the negative…” he says. “When I think of justice, I think this classroom and T.E.A.C.H., in general, with all of the classes, is doing each other justice. Because at some point in life, there was something that was missing from ourselves. The opportunity that we never had. So by us teaching each other something new; something that can empower us, I think is doing each other justice.”

Ω

[…] Teaching Education and Creating History program has recently been featured in the documentary Since I Been Down. Sherrill says the group’s work has achieved a grudging respect from prison administrators, in […]

[…] Teaching Education and Creating History program has recently been featured in the documentary Since I Been Down. Sherrill says the group’s work has achieved a grudging respect from prison administrators, in […]

[…] Teaching Education and Creating History program has recently been featured in the documentary Since I Been Down. Sherrill says the group’s work has achieved a grudging respect from prison administrators, in […]