Yonns Getahun (REDEFINE magazine):

Emmanuel and Salaiba, thank you both for this profoundly moving and poignant album.

During our last in-person rendezvous in early June, Emmanuel, we were at a political rally for racial justice and reflecting on American social and political realities. Based on that interaction, I assumed that you two must have started and finished this EP in the fifteen days following the rally. That perhaps you were responding to recent events around the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery — but this project has been in the works for at least two years. Is that right?

Emmanuel Whyte (Visual Artist & Poet):

Firstly, thank you Yonnas and Vivian for inviting us to have this conversation.

Salaiba and I recorded these tracks back in the fall of 2018. I was making my way across the country from Vermont, and we reconnected in Indianapolis. At the time, I had a whole lot on my heart. Namely, I was homeless and felt myself slipping further into reclusiveness. So, traveling and reconnecting with friends was a way to break out and cope with all that was on my mind. Salaiba is the type of person to meet you where you’re at, and we had five years of catching up to do.

I’d say this conversation, between Salaiba and myself, has been in development since we met. There’s never enough words to really comprehend or truly explain, you know, everything you felt in a year’s time, let alone five. Getting together for the first time back in 2018 and creating allowed me to explore issues like politics, and share poetry in a space of comfort. You know, I’m just kind of going through my mind right now, but I think in the long run, Soft Human Theory is a conversation, above all else.

And what I’m attracted to or what I’ve been looking at investigating for a long time aside from just, you know, playing Blackness, which I feel doesn’t really get you anywhere, is just examining my own masculinity and, and looking at what it means to be a man. Because those are things I can answer directly. And, you know, obviously a racial identity has its place, but I think around 2018 we were in the thick of the Me Too movement. Four years before that, I was just graduating school, and my Watson fellowship, as you know, was about going out, learning to be an artist, and in the process, understanding masculinity and questioning every facet of myself.

Salaiba Parnell (Guitarist):

I completely agree. What Emmanuel is saying about Masculinity is big. It kinds of reminds me a little bit of Joseph Campbell’s Hero Journey. Emmanuel is in the middle of this huge transition and literally is traveling across the country. And I am also in the midst of this very large transition in terms of my music and what I’ve been working on, and how I’ve been involved in the community. And both of us here are two young Black guys who are probably different from the mold.

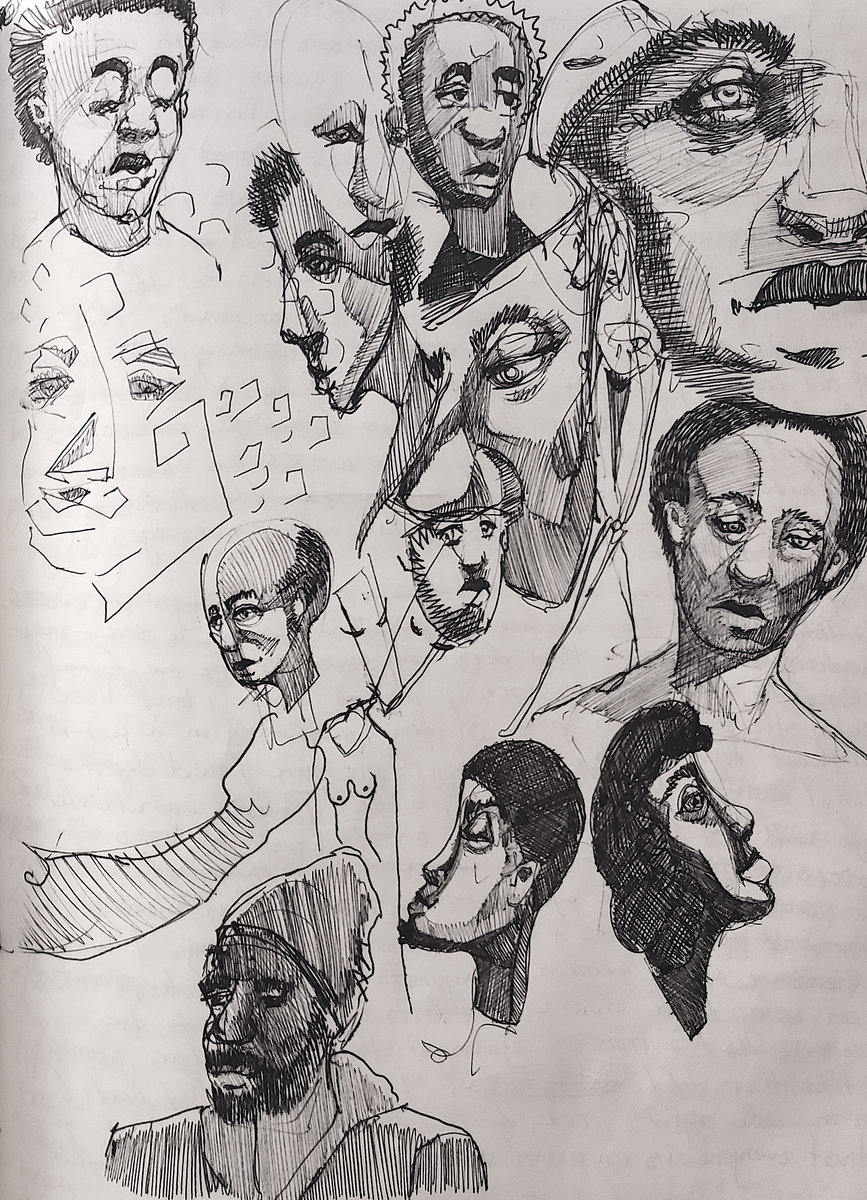

Glory I, 2018, 48″ x 70″, mixed media on pages from Icon #2 (Milestone Media, 1993), woodblock print, acrylic, beeswax, resin by Philip Crawford

Philip Crawford is a American artist based in Berlin and Philadelphia. He considers his research-based practice as primarily archeological: a slow and systematic chiseling away at popular heroic narratives from history, mythology, and fantasy in order to understand the cultures that produced them. The images, objects, and statements he appropriates become narrative frames and material resources for an interdisciplinary practice that includes critical essays, works on paper, installation, and performance. Philip holds a B.A. in History from Stanford University and is an MFA candidate at the Tyler School of Art.

We’re kind of two oddballs who have found each other and become really good friends. And so in terms of Soft Human Theory, the reason why I came up with the title, which is based more on research I’ve been doing, is because I feel like in our society, especially as men, especially as Black men, we are constantly taught we have to be tough. We are constantly taught that we have to be strong. We have to be aggressive. We have to be angry. That’s the only way we could show emotion. That’s how we’re judged. It is subliminal how our society perceives men and if you’re trying to come from a healthy place, some people don’t consider you as a man. And so within that context, Soft Human Theory is about the fact that society is trying to tell us to chase after money, clothes, and status but at the same time every human feels insecurity.

Every human feels heartbreak and loneliness. The only irony is that since we all feel like that, it’s almost like this trick of the brain where we forget that everyone else feels the same things. Soft Human theory is about the fact that if I feel an emotion which someone else also feels then we have more in common than we don’t. It is a call and a reminder of who we are in our vulnerability so we can honor others when they are in their vulnerability.

Whyte:

Precisely!

When a wind fans it the flames

are carried abroad. Talk

fans the flames. They have

maneuvered it so that to write

is a fire and not only of the blood.”

– William Carlos Williams

Getahun:

So what came first, Emmanuel & Salaiba, the idea or the sensuality of fire? How did your project Soft Human Theory come to be?

Parnell:

For me, it was definitely the sensuality of fire. Initially, we were just hanging out, and Eman was talking about some poems he wrote. He read one, and I played something, and we were just initially recording things on my cell phone. At that point, we realized that there was something there, and on the last night of Eman’s visit, we decided to record the album. I remember opening up my blinds so that we had a clear view of the sky and stars when we recorded, to give us greater clarity and perspective, and to allow our creativity to have a feeling that transcended my normal Indianapolis apartment.

During the recording process, I feel like there were multiple moments of clarity, where there was this inner sense that what we were recording was significant and meaningful. Like the stories that we were sharing through words and sounds would echo in the hearts of others.

Whyte:

The sensuality of fire, for sure. That is, if you mean whether a preconceived idea manifested vs. a more spontaneous response to the kindling of the first night or so. And I love how you reset the stage, Salaiba. The lights were low, mood meditative and we just flowed. I felt those moments of clarity most when we were completely freestyling, like in ‘Bird in Hand.’ As someone who typically creates within the comfort of my own campfires, so to speak, it can feel uneasy following someone else’s lead, especially that of an excellent musician like Salaiba. But there is a sensitivity I recognize in the way that he listens and alters the tempo and melody on a dime. There’s a dialogue going on beyond the lyrics. And it reminds me of dancing.

Parnell:

I had dealt with very challenging experiences at that moment when Emmanuel was visiting. And so part of it is almost like the deconstruction of masculinity. Right! It’s like ‘Fragile Masculinity’ and there’s a lot of it that is almost deconstruction of what is an assumed identity. And so I definitely agree with Emmanuel in the sense that, like, I think it’s almost like we have our own language within the album, and sometimes it’s hard to translate it but it’s based on the questions that are being asked.

Though the album feels very political since it was released in 2020 when it was started in 2018, it was much more about our personal experiences and what it meant to be an advocate on a small level. Like Veiled Eyes, the third record on the album, was about that sort of darkness that we see within our society. When we recorded the album, it wasn’t a hot topic like it is in 2020. And so it was much more about our personal relationship with that darkness rather than it being like this big phenomenon that everyone’s talking about.

It is very personal. And I think, and I hope that it strikes people on a personal level.

I think Emmanuel and I do have very complex relationships with how social justice is happening, what is being pushed and what may be on the margins. And that is a whole different conversation.

This album is more in the context of Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. It affects us humans and we all kind of experience it differently. Every human feels alone and lonely sometimes, and that is a different context which is more universal, if that makes sense.

– bell hooks

Whyte:

I lead with my heart, and I’m somebody who loves out loud. And I’m trying to understand what that means. bell hooks talks about being a warrior of love. What does that mean? To me, it’s like you are throwing two different things that should otherwise clash together. Love is war. How can you be a warrior of love? I think that being a warrior of love is somebody that has a deep capacity to feel and whether they’re an empath or not, they recognize they are not alone in their suffering. I’m not just talking about something religious. I’m talking about something purely human.

Many of us are so splintered and confused emotionally, especially as our feelings are branded and our movements, every one of them, are politicized. We try to cling to an absoluteness about our identities and find it hard to reconcile that we may be different people going from home to work to school and generally out in public. So if I went the route of just purely thinking and acting as a Black man should and understanding my position in the world accordingly, in terms of Blackness and all the forces that define it – other than my own self, then I’m going to be torn apart as if I’m at the bottom of a sea.

I’ve spoken to Salaiba about this, more or less in passing, because we’ve been in the process of releasing this for a while. I think there’s trepidation because even though I’m somebody that loves deep conversation, jumping between the abstract and the real, and even though I am romantic I keep a real eye on the world and a heart on the world. I find it hard to feel like my feelings are legitimized and to feel like the way I am entering the larger conversation is justified.

We can’t be in a position where it’s hard for somebody to stand up because they don’t know whether or not their feelings are legitimate or not. That’s, that’s terrible. That’s violent. And I think a lot of times, because we are so splintered externally, we do it to ourselves. We police ourselves. You know?

So I try to make it personal, at least to create a conversation around the nuance and express that it’s ok to love. It’s ok to be confused.

Getahun:

So in this project you are drawing us from the abstract and political to the personal?

Parnell:

One thing that Emmanuel hasn’t really talked about that I think is also really important to understanding this album and understanding our perspective, also through COVID, is an inherent nature of who we are as people, which is spiritual. That is also part of the reason why we called it Soft Human Theory. We’re talking about universalism, right? Sort of the idea that Bob Marley is a great example of an artist who was moving in that direction and also someone who came from multicultural backgrounds.

And I think for me, the other part of it is the fact that this is a spiritual journey and it’s spiritual within the context of what Emmanuel is talking about; the panopticon. This whole Foucault’s discourse on power. We have both read about this stuff in college and we understand the way that power can seep in through every single thing we’re watching; the way we perceive ourselves and that identity can be inherently political.

All of us have a perceived norm of what’s happening in society. Generally when we go to a job interview or we’re in an unfamiliar social situation, we try to steer towards the perceived normal because that means we’ll be accepted. However, some people are just completely different no matter how much you can dress them up. Emmanuel is a great example for me here.

You have this really powerful, physically, and very smart artist who was also a football player. Also he is super international and you have all of this in one person. You have me who is very political and can be calculating within the right context but also super spiritual and gentle. So you’re dealing with these identities that are inherently, for me, antithetical to stereotypical masculinity.

– Walt Whitman

Also as we grow personally and spiritually, and as we become more in tune with who we are, as Emmannuel said about vulnerability, it’s also about creating a space where everyone who feels different belongs. And it doesn’t have to be so big and grandiose.

As people who are different we’re creating something that says, “Hey, it’s okay to be different and it is okay to be conflicted about masculinity and it’s okay to feel and voice things that the media isn’t really talking about.” So for us the political and the personal are connected.

Getahun:

So it’s a personal freedom that you are saying is available, possible or you’re pulling us toward?

Parnell:

I can completely agree with you. Yes! As a person that is my most motivating feeling, the feeling of freedom.

The last part of it, to tie it back, between this deep political analysis of what identity means within this financially driven world and the spirituality, I think, is this whole softness. As a human being, almost everyone experiences, some type of love story in their life, whether it’s romantic or parents or a family member or a friend, like there’s some sort of dynamic, some sort of loneliness versus being together in society. There’s some sort of how to be an individual versus fitting in within the community. There’s some sort of feeling like a leader versus someone who is following someone else. There are all these different dialectics and different problems that every single human experiences. Like dreaming.

So that is the thing, Soft Human Theory, for me, for my music and what I am doing musically is to remind us that no matter how much our society is saying that we’re so different, we all share these common experiences. And the point is, when you get outside of what everyone is trying to tell you is important, we have a lot in common. If we can remember that we can actually build real community.

Getahun:

On the topic of music and composition, Salaiba, I hear influences of folk, funk, and even hints of flamenco. When composing what direction did you set out on?

Parnell:

I think that a lot of my playing on the album was influenced by what I was playing at the time. I was very focused on soul music and jazz, so a lot of those techniques and sounds were in the record. I’ve always loved the feel of folk, and thought that the fingerpicking for “dreaming with eyes wide open’ was a good way to create an intimate feel while keeping a specific rhythm. I think a lot of my playing was also influenced by Eman’s lyrics, I was constantly trying to respond to the stories and words that he shared, and I think there is a lot of dynamism in my playing which represents his thoughts on various topics.

Getahun:

One of the lyrics there is an indictment against ivy league school. Suggesting it is a disappointment in that how it produces and what it produces is not justice, or morally right, but more often than not morally bankrupt and unjust. Is that analysis in the right direction?

Whyte:

I mean, it’s a big question. I care a lot about how we are being educated and I know that there are internal issues that higher ed. have been facing for decades in regards to the lived realities of their students clashing with the institute’s speed, ability and desire to accommodate.

When considering my relationship to it, I think of the colonized mind, or the idea that we are taught to think, but not to think for ourselves. I don’t want to be caught in the schism of feeling like everywhere I go, I’m feeling betrayed or oppressed, but there are realities – historical, systemic realities that ceaselessly rear their ugly heads.

It’s easy to make the connection between school and the market, because it takes money to run a school. Calls for divestment are one way students and faculty alike are protesting the school-money link but I’m more concerned with how we are learning and the grinding pressure associated with it.

For example, I remember getting so aggravated when “privilege” was getting attached to everything and I remember raging against the expression “white privilege” years ago. I despised it, not because I rejected its validity, but because it didn’t seem like a productive way for me to think – by considering all of the privilege you have, and how your privilege is undoubtedly oppressing or disenfranchising someone. White privilege, cis-male privilege, tall privilege, thin-privilege. Focusing so much on defining an oppressor just felt more divisive than uplifting or empowering. In any case, I felt that it created an atmosphere that was akin to walking on eggshells in conversations and they often dissolved into pointing fingers and terse assertions that someone needed to check their privilege. Ok, cool. Check. Let’s talk solutions and accountability now.

I feel that schools can be so distant from the general public to the point where they will be situated right in the middle of a community and never develop a system to liaison or establish a direct communication to the community leaders there. Rather, they will merely see them as “townies”.

So you have students absorbing a curriculum that teaches them theory. Then they go out into the world to proselytize these things, subjecting the general public to new terms coined inside their institutional bubbles without getting to know people and see them where they’re at. It’s more complicated than that, but you can’t subject people to your ways of thinking without inviting them to the table.

I think BIPOC is the newest term that’s come out in an attempt to accommodate and address “diversity and inclusion”, but how in the world can you expect to lump us all together and expect to solve anything? My experiences as a Black American will be drastically different than a Jamaican that’s just gained American citizenship. Let alone how much the lived experience of a Black person varies with that of an American Indian, or a Chinese American or a Puerto Rican, or a rural white American subjected to similar hardships as so on and so forth. These are superficial markers that never get to the root of an issue and more often than not just have us tripping over our own tongues. They don’t care about how you’re naming them. They just want the things that they need. To survive and get by and make them happy. Like everyone else, you know? So it’s, it’s the larger conversation that I just really want to slice through with a Samurai sword.

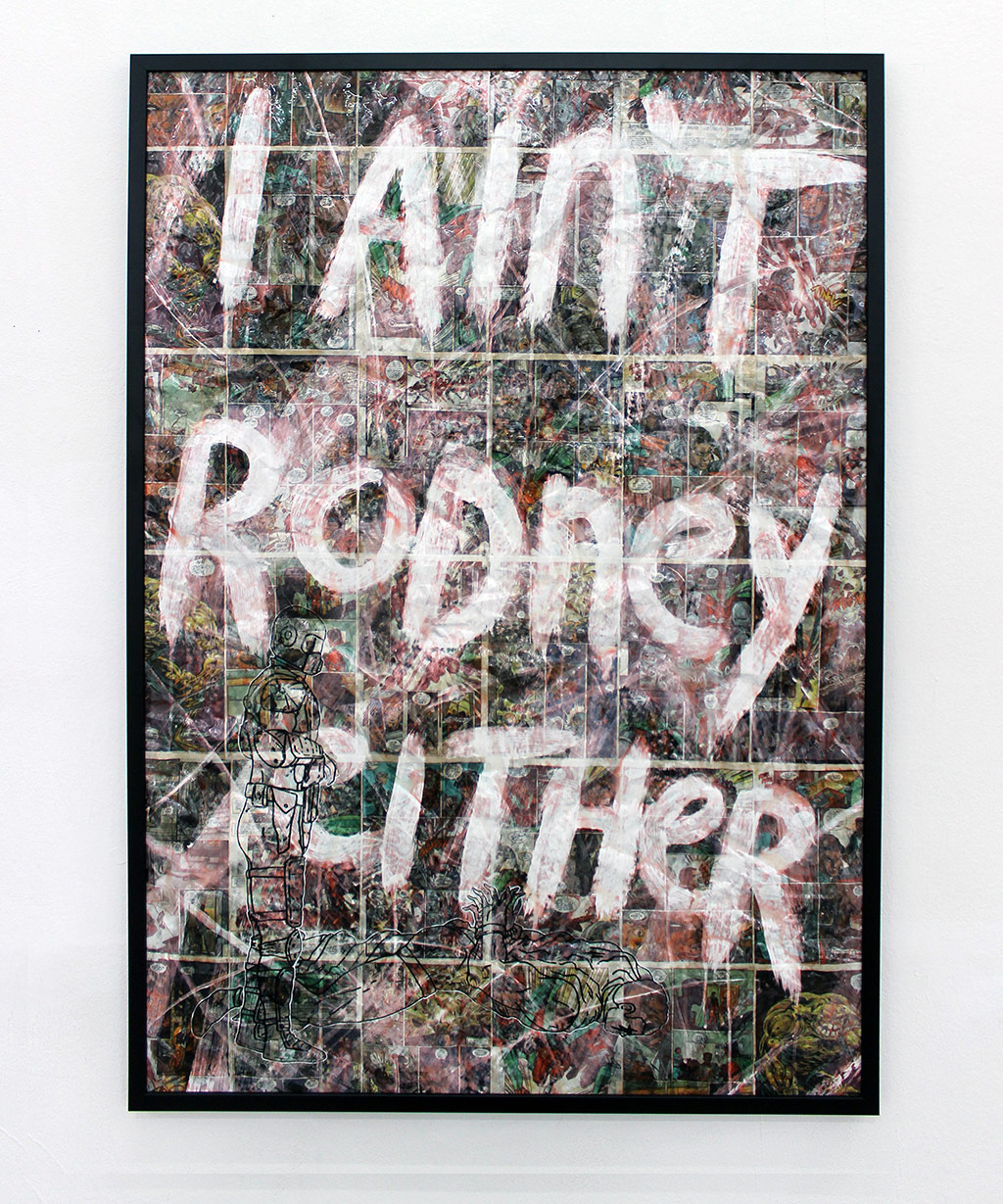

Glory I, 2018, 48″ x 70″, mixed media on pages from Icon #2 (Milestone Media, 1993), woodblock print, acrylic, beeswax, resin by Philip Crawford

Glory I and Glory II are part of a larger series called Stop!Cop!, a body of work investigating issues of systemic violence and the discursive use of images of victims of police brutality through the lens of a 1993 comic book, Icon #2. These two mixed-media works adopt a phrase penned by the creators of the original comic book which revealed to me the conflicted space between victimhood and resistance that many black(ened) people are forced to negotiate. I read the simultaneous indictment of both Martin (Luther King, Jr.) and Rodney (King) not as a simple call for violent resistance, but as a moment of violent awakening. In these statements, there is a realization that the contemporary “I” must refuse the two dominant expectations for black publicness exemplified by each man. Following the revelatory moment, the question of “How?” is left to the action or inaction of the speaker/reader/audience.

Getahun:

So what is possible, integrity wise, freedom or expression wise, in album together, in comparison to writing a dissertation? What is it about getting these ideas across that works for you in an album versus any other method; writing a blog piece, a dissertation or going to graduate school? What is the freedom that you find or is there a freedom that you’re able to find an artistic project like this?

Parnell:

I have a couple of things that I want to respond to what Emmanuel said and then I will respond to your question.

So first of all, let’s get a little snapshot here. Here I am. This Black kid grew up in Alabama and went to a private school. When I was in Alabama I had a couple of racist teachers, but I did not have peers that were racist. I mean, they might’ve disliked me because I was a nerd or different things like that but it wasn’t because I was Black.

Yet I went to a very elite school for college, and that was the first time I really dealt with racism from my peers. Not only from my peers, but from the institution. One of my friends, who is from California, and who is a good friend of both Eman and I said one of the truest things about our school; “it was never made for us.”

In some ways it felt like we were tokens who were shipped there to make the school look good without the school making any institutional adjustments to make us fit in. The college historically has been an institution through which those with power have been able to prepare their children to follow in their footsteps and become powerful, national leaders. So I think within that context, obviously, if that school is set up to train the children of our nation’s leaders, then of course it’s going to adhere to what the leaders want. And the people who don’t fit into that are going to have to deal with controversy and all these things.

I completely agree, in terms of academia. I was in a PhD program for political science, and one of the reasons why I left is because of what Emmanuel said. I mean, again, we were studying political science and all this stuff, and no one mentioned the Occupy Wall Street movement.

On top of that, in grad school I experienced just extreme amounts of racism. My friend had a breakdown at a bar because he just couldn’t deal with it. We were out drinking and he broke down and started crying in the bar. At that moment he couldn’t deal with the fact of how messed up it was being Black there. Right! We used to go out and party and we’d have to leave,both of us, we couldn’t deal with the social interactions that we had to deal with because of how messed up it was and how opaque it was for other students. This was a consistent problem for so many Black students but it wasn’t effectively addressed.

And I think that’s why it’s important, I feel like a lot of Soft Human Theory, is these varied personal experiences that also have a universalistic context. Because what Emmanuel and I experienced in college was not very different from what a lot of our peers experienced.

I mean the Black community at our college has always struggled, in part, because Black people from there leave and never come back. Never talk about it like PTSD or something. I mean it is scary.

You’re talking about THE NUMBER ONE school for liberal arts in the whole country, number one, and has been for a long time yet all these people of color, all these people who are queer, all these people who were not white and straight, they never want to talk about going back.They don’t donate. They don’t want to hear about it. No, period. So what does that really mean? Like what does that really say about it being number one? What does it say about it being the best?

Getahun:

Wow! Wait! You both studied and pursued post Bachelor degrees?

Whyte:

Only Salaiba. Not me. I guess I have been applying. I have applied for three years straight and was accepted to two of my top choices, but did not want to take on the debt.

Getahun:

I am also now reflecting about my experiences in higher education. How there were series of experiences that did not recognize my full humanity like I was a box being checked off. Thanks to your points I now find myself wanting to ask some of my past counterparts at University of Washington and their analyses: “Do you see my humanity or do you see the humanity of those that you’re talking about?”

Parnell:

So in terms of what you just said, and this is like my personal experience, I can’t speak for Emmanuel,but I feel like intuitively, we are coming from the same place. Emmanuel, correct me afterward.

But there’s no amount of words or books that can make you care about somebody. That can make you sit down and listen. I mean, it’s important and all these categorizations are important because we have academia that needs to create ideas and things like that.

However, the Humanity, that’s what is missing. You know, the kids who are most successful are sent to these educational institutions. These professors tell them, this is what race is, giving them all these theories and all this discourse but we’re not told how to really care for each other and how to really bridge cultural divide, how to be humble and listen to someone instead of assuming theory that we learned in college will explain all parts of them.

There’s a lot of false assumptions that happen. And to go back to what you asked about a few minutes ago, “what’s possible in terms of integrity, freedom and expression in an album versus a dissertation or a book?”

I think part of the reason, why I was pretty adamant the album was going to be for free, is because a lot of what I’ve done that has been termed successful in terms of music and creating community has been on the margins.There is a huge underground scene here in Indianapolis, which is where I live.

There’s a huge underground music scene and underground spirituality, because those are the places where the discursive communities could actually be authentic. You know, because they don’t have to fit into the boxes of whatever it is; gender, race, religion, etc.

Or here is a recent experience with a friend. I was sharing with her where I was in the doctor’s office and there was this white guy who I personally felt was giving me some real racist vibes. And I was like,’oh, that’s kind of weird.”

And her response was, “Why didn’t you say something? Why didn’t you do this and why didn’t you do that? Because maybe you could have confronted him.” And I was like, “You know, in my personal opinion, I think , honestly, the way for us to really touch people’s hearts are when they’re open and receptive.”

So if someone is being defensive or angry or something like that might not be the best time to approach them and that’s why I think art and specifically music as well as movies are so powerful. When people are watching something or listening they’re receiving. They are just vibing with whatever is coming to them. That’s a way to open people’s hearts and minds to difference and different experiences in a way that is much more powerful than having an intellectual argument about the topic.

Getahun:

Yes. Damn! Y’all are so fucking fresh. I love this!

You ever get into a room and ask yourself “I don’t know how I got here but I love it.”

The reason I can say that is because I can so understand how liberal institutions or studies failed me. Let’s make it personal, in some of these referenced ways. While I was going to the University of Washington in Seattle I was hosting and organizing open mics and poetry readings and producing concerts, but what I can get in those experiences versus what I got in the classroom, which was its own way of talking and being, were two different things.

And one was definitely more human, and shared and communal versus the other which was very structured. I can see now how one is relegated to create policy. What you mentioned about how these students end up creating policy and governing the rest of us while really not being connected or seeing the community they believe they are serving.

Whyte:

They never do!

We tend to go straight through the pipeline. And Williams College is one of those schools where you’ll have kids all really smart and bright go through school and just go right back to school and continue. They’re no doubt incredibly bright, doing top notch research and doing their due diligence to make themselves valuable members within communities. The bottom line is I think that a lot of people, a lot of teachers today get their exposure from quick and fast internships, really nice concrete textbooks that just keep getting updated with new pictures but they never go out into the community to spend time, gain trust and ultimately invest. Unless it’s something that’s sanctioned, assigned, but rarely out of soul humanistic exploration. So yeah, I agree with Salaiba.

You’ll never convince me in words to care about you or care about a subject. You have to understand I grew up with poor white people in Vermont. Vermont is a welfare state and it attracts a lot of poor white people on Section Eight, federal funded housing, et cetera and that’s my experience growing up. We experienced homelessness and we received WIC as a bare essentials food service. Yet the complexity is I’m in a position now where I will sometimes talk to my friends about racism and, and they’ll ask “have I been racist to you growing up?” Yeah, my friends could be pretty damn ignorant at times, but they sure as hell loved me, you know?

And there’s no doubt about it. And it’s not that they don’t see races. It’s not that we’re not having these conversations but I think that in the grand scheme of things, what the Institute has pushed down on us is that these should be really hard polarizing, squeamish conversations, but it’s like, no!

The general populace that we tend to talk about; people of color, black people, indigenous people, et cetera, already speak a different language. It is up to us to see them where they are at. To hear them out. Chances are we’ll find that we laugh at the same things.

So, on one hand I don’t want to fight my way to get into school only to be trapped in a language that further distances me from the people that I really want to communicate with because I already feel distanced. On the other hand, leveraging your education and associated status is one way to bring issues to the forefront.

Getahun:

You answered the question for me which is: in music, art and in lyrics, you can address complexity and subtlety.

To recall an earlier comment by Parnell: if all the Black, POC, and queer scholars who attend these universities — or pursue and complete undergrad, post-grad, and PhD programs — leave and never come back to these institutions, where do we go? Where do we congregate and reflect on what we’ve experienced?

Ω