“The media’s the most powerful entity on earth. They have the power to make the innocent guilty and make the guilty innocent, and that’s power. Because they control the mind of the masses.”

– Malcolm X

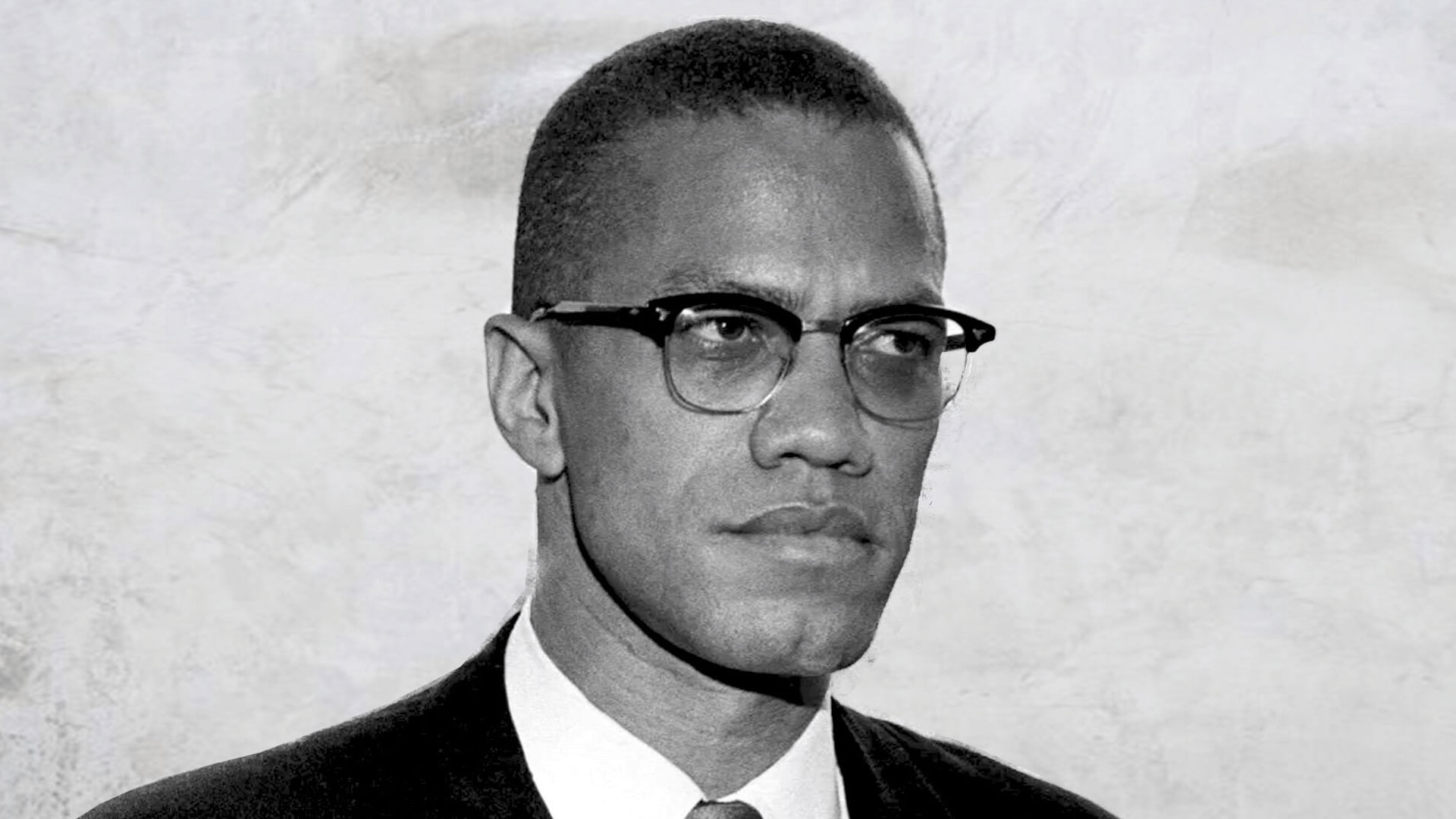

MALCOLM X (1925-1965)

Malcolm X — born Malcolm Little and later known under the Muslim name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz — knew from a young age that he was not long for the Earth. Whether it lay in his intuition or his inheritance, early deaths ran in the family; his father was a preacher who many historians believe was killed by white supremacists, and five of his father’s six brothers fell to violence.

Malcolm X’s sense of intuition, though, he attributes to his mother, who in fact predicted the death of his father. In The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to journalist Alex Haley, he recalls:

“It was then that my mother had this vision. She had always been a strange woman in this sense, and had always had a strong intuition of things about to happen. And most of her children are the same way, I think. When something is about to happen, I can feel something, sense something. I never have known something to happen that has caught me completely off guard-except once…”

In the book’s epilogue, Haley is reminded that Malcolm X once told him, “If I’m alive when this book comes out, it will be a miracle” — and indeed, though the two began collaborating in 1963, the book was published posthumously after his assassination in 1965.

As Malcolm X’s sole published piece of writing, the autobiography was driven by his urgent conviction that white society could not be trusted with retelling his story. As he hints:

“When I am dead — I say it that way because from the things I know, I do not expect to live long enough to read this book in its finished form — I want you to just watch and see if I’m not right in what I say: that the white man, in his press, is going to identify me with ‘hate.’ He will make use of me dead, as he has made use of me alive, as a convenient symbol of ‘hatred’ — and that will help him to escape facing the truth that all I have been doing is holding up a mirror to reflect, to show, the history of unspeakable crimes that his race has committed against my race. You watch. I will be labeled as, at best, an ‘irresponsible’ black man…”

Upon his death, major U.S. news outlets unflinchingly continued to push forth a negative view of Malcolm X. On February 22, 1965, an editorial in The New York Times harshly stated, “The life and death of Malcolm X provides a discordant but typical theme for the times in which we live. He was a case history, as well as an extraordinary and twisted man, turning many true gifts to evil purpose… Malcolm X had the ingredients for leadership, but his ruthless and fanatical belief in violence not only set him apart from the responsible leaders of the civil rights movement and the overwhelming majority of Negroes. It also marked him for notoriety, and for a violent end.”

Malcolm X was labeled as “irresponsible” while others like Martin Luther King Jr. were labeled as “responsible” — but the reality was that they grew closer in their values as they became older. Following his trip to Mecca for Hajj in the summer of 1964, Malcolm X was no longer as obstinate about working with those he had previously termed the “white devil,” for the experience opened him up to a new way of thinking. From Hajj, he writes:

“There were tens of thousands of pilgrims, from all over the world. They were of all colors, from blue-eyed blonds to black-skinned Africans. But we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and non-white…

You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to re-arrange much of my thought-patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions.”

Following this, Malcolm X traveled the world and backpedaled on some of his previous philosophies, eventually even concluding, “The white man is not inherently evil, but America’s racist society influences him to act evilly. The society has produced and nourishes a psychology which brings out the lowest, most base part of human beings.”

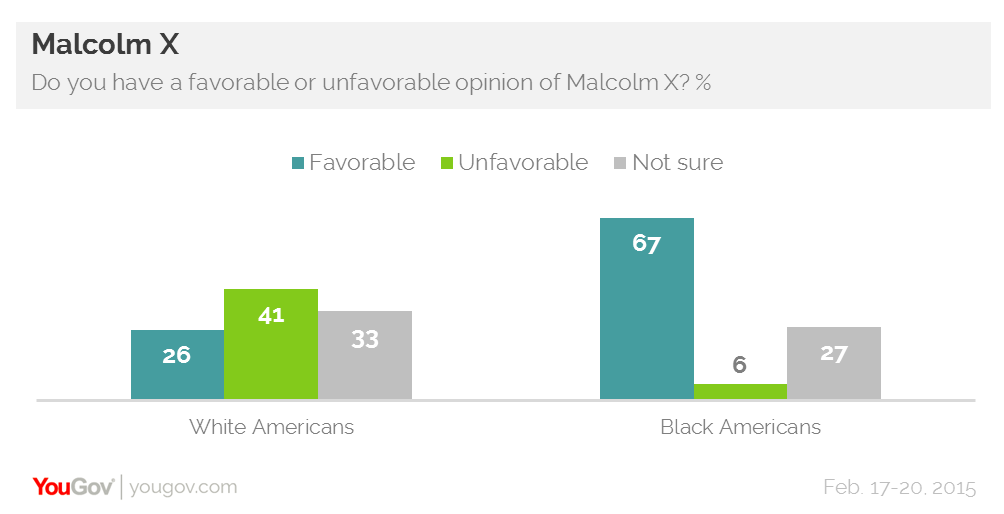

To this day, most white Americans remain preoccupied by the idea that Malcolm X is a violent thinker, but even whites sympathetic to his story have often failed to recognize his complexities. In 1968, writer James Baldwin was given an opportunity to write a screenplay on the life of Malcolm X but found it torturous. He saw a conflict between the complex, multilayered narrative he saw and the limited image that Columbia Pictures wished to push, which was a story of victimhood — one where “the tragedy of Malcolm’s life was that he had been mistreated, early on, by some whites, and betrayed (later) by many blacks.”

Nevertheless, Baldwin did eventually produce a final product, with the assistance of blacklisted writer Arnold Perl. The script was sold to Warner Brothers but ultimately buried; in 1972, Baldwin went on to independently publish the script under the book title, One Day When I was Lost.

Two decades after Baldwin left the project, Spike Lee was brought on to the original film project and insisted that the film be made by an African American filmmaker. Lee’s film, Malcolm X (1992), was eventually produced by Warner Bros, starred Denzel Washington, and took great inspiration from the original screenplay Baldwin and Perl had written. Nonetheless, save for a sympathetic review from Roger Ebert, the film was not well-acclaimed upon its release. Variety called it “a disappointingly conventional and sluggish film,” and it was otherwise described often as tedious, with reviews feeling as though it were not nearly “angry” enough to represent a figure with just such a reputation.

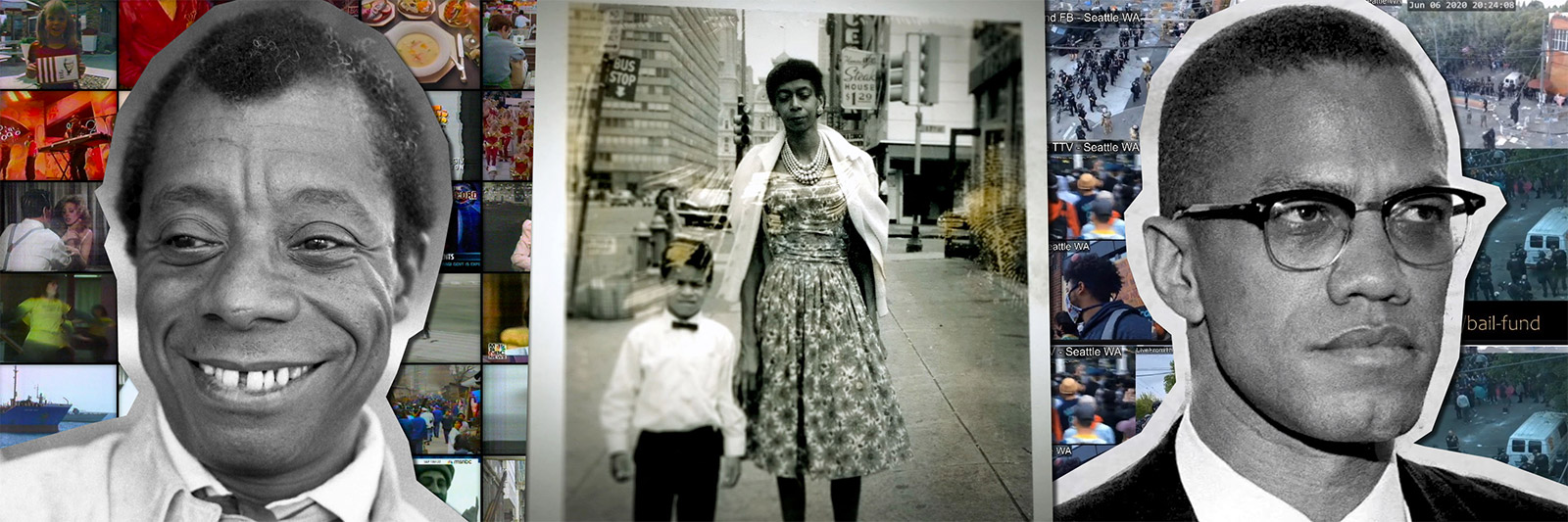

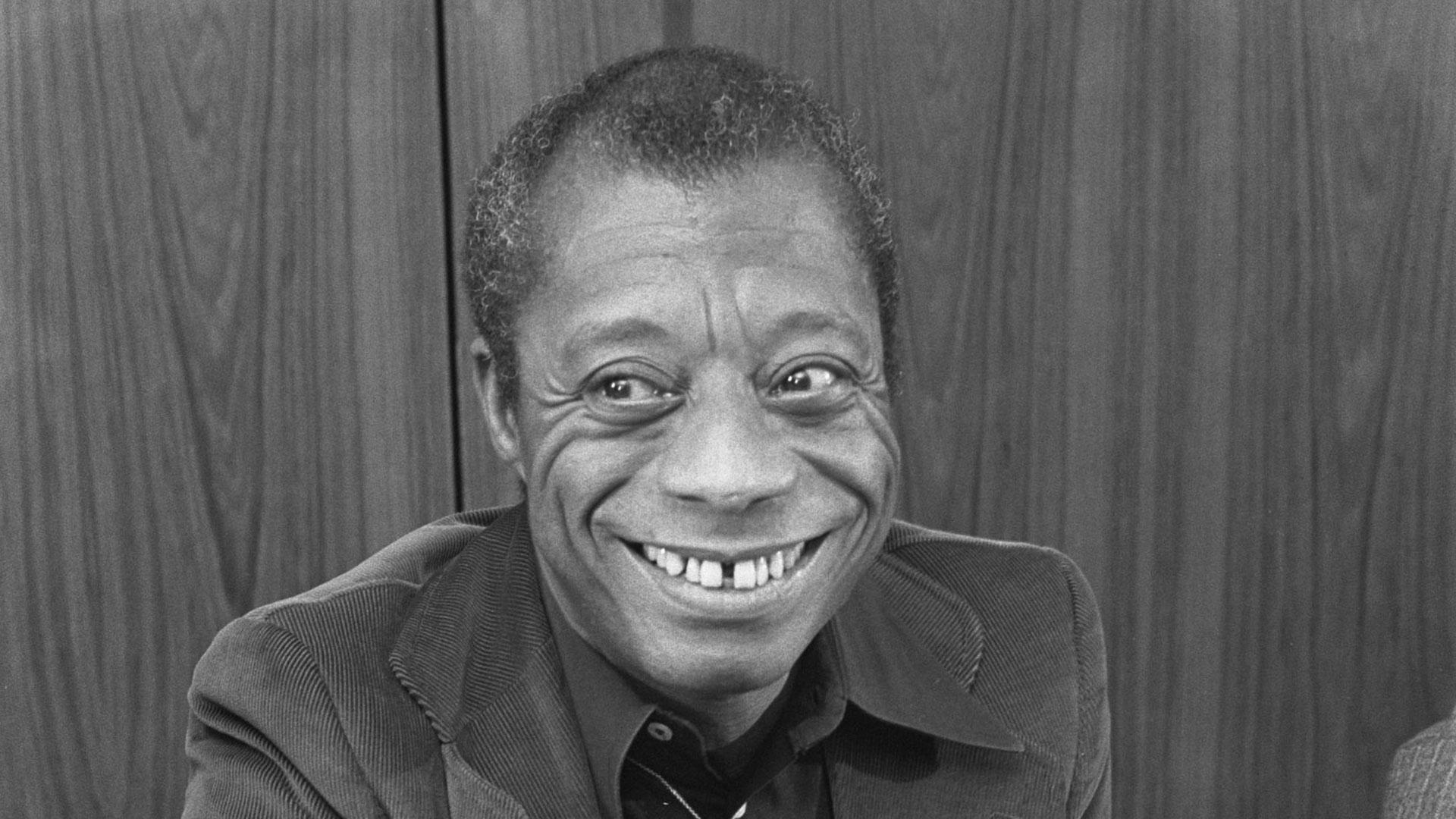

JAMES BALDWIN (1924-1987)

Based on writer James Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript from the mid-1970s, entitled Remember This House, the documentary I Am Not Your Negro (2017) sets the stage by comparing three contemporaries of Baldwin who were assassinated in the early-to-mid-60’s: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Medgar Evers. Regarding the complex relationships among these civil rights leaders, Baldwin says, “I want these three lives to bang against and reveal each other, as in truth they did — and use their dreadful journey as a means of instructing the people whom they love so much, who betrayed them, and for whom they gave their lives.”

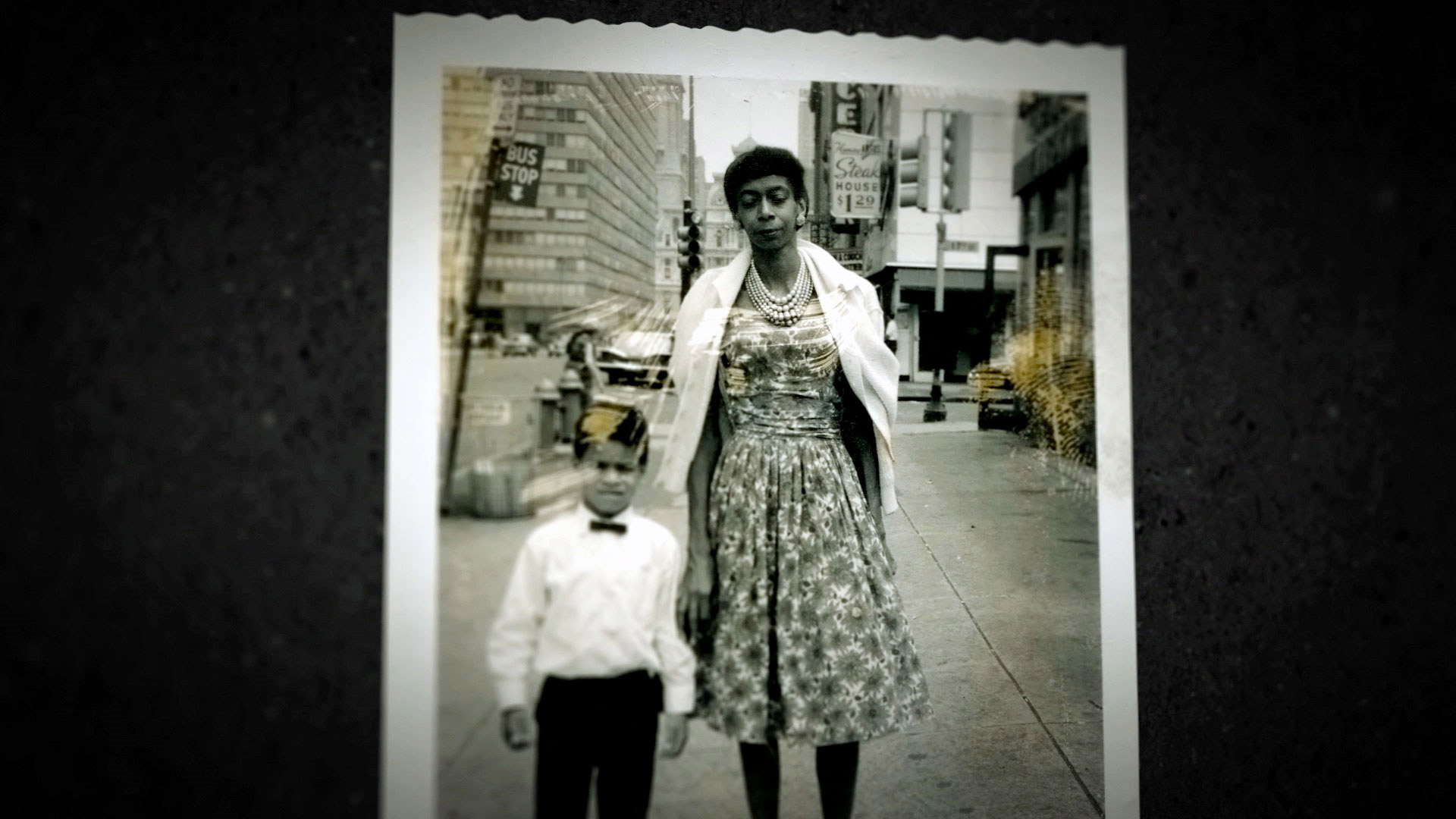

By comparing his life to that of these three thinkers, Baldwin was able to clarify his role as a self-described “witness” — one who observed, synthesized, and then presented his observations to the world at large. His astute observations employ powerful storytelling techniques to convey the experience of being Black in America. In I Am Not Your Negro, for instance, he comments on the lack of Black representation in film by sharing a poignant tale from his childhood. It is introduced by a photograph of young Baldwin wearing a cowboy hat.

“It comes as a great shock, around the age of five or six or seven,” Baldwin states, “to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians — when you were rooting for Gary Cooper — that the Indians were you.”

At this juncture, the mostly-white audience begins to laugh, until Baldwin somberly continues, “It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace, and to which you owe your life and identity, has not — in its whole system of reality — evolved any place for you.”

The audience then falls silent.

Throughout his career, Baldwin was frequently given the opportunity to speak at prestigious institutions and on highly visible platforms — yet he was at times forlorn that his life’s work was to witness, rather than engage in direct action. In I Am Not Your Negro, he compares himself to other civil rights leaders, saying:

“I did not have to deal with the criminal state of Mississippi hour by hour and day by day, to say nothing, night after night. I did not have to sweat cold sweat after decisions involving hundreds of thousands of lives. I was not responsible for raising money or deciding how to use it. I was not responsible for strategy, controlling prayer meetings, marches, petitions, voting registration drives. I saw the sheriffs, the deputies, the storm troopers, more or less in passing. I was never in town to stay. This was sometimes hard on my morale… but I had to accept as time wore on, that part of my responsibility as a witness was to move as largely and as freely as possible. To write the story, and to get it out.“

Following the government-sanctioned murder of so many of contemporaries, Baldwin became convinced he could not survive American race relations, and began to spend extended periods of time in Paris, even living there for the last 17 years of his life. He was prolific — publishing dozens of plays, essays, collections, and novels — yet even while abroad, his experiences in the U.S. never left him.

In the short film, Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris (1970), Baldwin desperately tries to convey to documentarians that the story they desperately wish to uncover is not what he believes is significant about his existence.

“I am not interested in Jimmy Baldwin’s Paris. I am not the least bit interested in my 22 years in this city. It’s of no importance at all,” he asserts. “What is important is that I’m a survivor of something and a witness to something. That is what matters, and that is all that matters. I’m not speaking for me… but I am a Black man in the middle of this century, and I speak for that, to all of you… because none of you know, yet, who this dark stranger is…”

“I’m not at all what you think I am,” he continues. “I am very different than that. I have something else to do.”

MARION STOKES (1929-2012)

In 1980, the reclusive intellectual Marion Stokes began doing something unusual. One year after the Iran Hostage Crisis and close to the invention of the 24-hour news cycle, she began to note shifting media trends and felt the impetus to begin recording obsessively. Aided by her nurse, secretary, son, and chauffeur, Stokes eventually filled 70,000 VHS tapes, firing up to eight tape decks at once during special events.

“The scale of Marion Stokes’ collection is absolutely unprecedented. No one in this field has ever heard or seen the like,” explains Roger Macdonald, Television Archive Fellow at Internet Archive, the nonprofit which has since inherited Stokes’ legacy. “What she recorded is inaccessible to us; all the long-form programming that she got, all the CNN, all the FOX, and then there’s the local news. That’s a rare collection. There’s probably elements that she has that nobody has.”

In a mere hour-and-a-half, Matt Wolf’s documentary, Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project (2019), uses notable societal events culled from Stokes’ collection and ties them directly into her life. Much of the film relies on first-hand accounts and snippets from Input, a current affairs discussion program Stokes co-hosted in the late ’60s. Input intentionally created a container for mutual respect, where experts and thinkers with conflicting viewpoints could be in conversation with one another around controversial topics.

“The power of mass media to affect public opinion was something that she became very conscious of,” her son Michael Metelits explains, “and she was aware of how the raw story gets filtered by the predilections of the people that were producing it.”

In his 1928 book, Propaganda, Edward Bernays, the Austrian-American thinker who is known as “the father of public relations,” writes:

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country… [who] understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.”

One year into the Iran Hostage Crisis, Stokes began to note that important information was gradually being lost as reporting on the crisis evolved, and that public opinion was molded by the shifting media depictions. It was then that she began to record around the clock, utterly convinced that she was the only one who would undertake such a monumental task. She was correct.

“She had an incredible ability to see trends and to act on them. It’s difficult not to call her a visionary…” explains Metelits. “She did give up a lot, in terms of what people think of as… normal human life, but she funneled all that energy into doing things that she felt were important to her; that were going to be important in the long run.”

Stokes recorded everything obsessively for over thirty years. In 2012, she passed away in front of her television as the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary unfolded. It was also the same year that Stokes called special attention to the murder of Trayvon Martin, the 17-year-old teen whose murder sowed the seeds for the Black Lives Matter movement.

“I presume that somewhere in [her] archive, you could pull out a sub-archive of racially-motivated police brutality,” hypothesizes Tom Keenan, a human rights and media scholar. “Going back and watching, in detail, how those stories get told, what sort of justifications are offered, what sort of unanswered questions remain…”

One gripping scene in Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project may offer some guidance. Over the course of nearly four minutes, a dissonant grid featuring four TV stations slowly captures the 9/11 tragedy as it unfolds in real-time, each transitioning one-by-one, away from their regularly scheduled programming. When they are finally in sync, each frame reveals a different depiction of the Twin Towers burning.

Driven by something greater than herself, Stokes amassed a collection which will inevitably prove illuminating. If the murder of Trayvon Martin — or any number of similarly contentious events — were analyzed through such a comparative framework, the potential for revealing and confronting media bias would be apparent.

Perhaps it is only when all perceived truths can be seen at once that the inconsistencies may be addressed.

“Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.”

– Frantz Fanon, In the Wretched of the Earth (Les Damnés de la Terre), 1961

Citizen Media (1991-2021+)

On March 7, 1991, as the Los Angeles Police Department’s beating of Rodney King spread through mass media, many Americans were introduced to the harsh reality of police brutality against Black people for the first time. Pre-dating widespread cell phone use, body cams, social media and livestreaming, this particular incident was captured by George Holliday with an 8mm Sony Handycam, cutting-edge technology of the time. As Holliday recalled 25 years later, he had no idea at the time what to do with the footage, until he called the local TV station, KTLA, who aired it that same evening during their news program. Holliday’s instinct to record the Rodney King beating marked the first widespread example of citizen media as witness to police brutality.

Eighteen years after the Rodney King beating came the 2009 murder of Oscar Grant in Oakland, California. Afterwards, an anonymous witness submitted video footage to the local station, KTVU, which then posted it on YouTube. Their choice of using a social media platform in addition to broadcast allowed for the video to go viral. The anonymous first-hand account served to show significant discrepancies between the officers’ accounts and reality, as caught on video. An extensive #OscarGrant hashtag campaign on Twitter — still a relatively new platform at the time — proved itself a useful tool for activists and civilians to coordinate around community organizing actions and subsequent police responses.

Three years later, it was the murder of Trayvon Martin — and the acquittal of his killer — which introduced #BlackLivesMatter and solidified the use of hashtags in the movement. In Allissa Richardson’s 2019 book, Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones, and the New Protest #Journalism, she details:

“When George Zimmerman was acquitted in the Trayvon Martin murder trial in July 2013, widespread disbelief and despair shook black community across the nation. The case had seemed very clear cut. Trayvon Martin was a child. George Zimmerman was armed, carrying a loaded 9 mm pistol. Still, the jury saw Trayvon as a threat. Zimmerman went free. A day after the verdict, Alicia Garza wrote a love letter to black people on Facebook. It read, ‘I continue to be surprised at how little black lives matter… Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.’ Her friend and fellow organizer, Patrisse Khan Cullors, reposted her words on Twitter with the hashtag behind it: #BlackLivesMatter.”

The 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri, directly formalized the Black Lives Matter movement, sparking protests across the country and even international shows of solidarity. According to Richardson, in the years that followed Ferguson, “scholars gathered more than 40 million tweets that were tagged with either #Ferguson, #BlackLivesMatter, or both” — a significant increase from the hashtag #TrayvonMartin alone, which appeared in more than 3 million tweets between 2012 and 2015.

“You have a generation that are getting fed up… and even though they don’t have what we call an ‘organized’ education, they’re intelligent individuals… they understand what it is to be oppressed, and they know when someone is trying to oppress them,” explains one protestor in Craig Atkinson’s documentary film, Do Not Resist (2016), which analyzes the Ferguson protest through its heavy police militarization. “As you can see out here now, they’re fighting it. And I think it’s going to be more than just Ferguson. I think it’s going to expand. I really do.”

Other high-profile police killings included the 2015 death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland, and the 2016 death of Philando Castile in a suburb of Saint Paul, Minnesota. Yet it was six years later, following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, that the Ferguson protestor’s words rang resoundingly true. What began as local protests in the Minneapolis metropolitan area quickly spread to over 2,000 cities and towns in over 60 countries. According to the New York Times, polls estimated that between 15 million and 26 million people had participated at some point in the demonstrations in the United States, making them the largest ever in U.S. history. Thus, the Black Lives Matter movement was reignited.

When one compares 2020 with the 2014 spark in Ferguson, it is evident that much has changed. In Sabaah Foyalan’s documentary Whose Streets? (2017), for instance, Ferguson protestor David Whitt runs a home-grown initiative called Copwatch, which uses camcorders and film as a deterrent for police brutality. “I don’t go out with any weapons or nothing like that… I go out with my camera; that’s my weapon,” he says.- “The fact is that since the police are not being held accountable; we gotta hold them accountable.”

The concept of holding police accountable through film and media saw a notable ramp-up in 2020 — made especially visible by abundant livestreaming and social media. Cities across the country saw entire ecosystems of grassroots journalists emerge to support the movement at the frontlines of every protest, often documenting realities not seen in mainstream media.

On a national scale, aggregators such as woke.twitch.tv attracted tens of thousands of viewers every night at the height of the protests. Simultaneously displaying numerous livestreams at once, Woke’s windowed screen-in-screen format echoed the side-by-side presentation of 9/11 in Recorder; all at once, viewers saw that police brutality and over-militarization looked and felt similar everywhere.

With each new development in media technology it seems that individuals, collectives, and societies adapt in search of new ways to witness. In Bearing Witness While Black… Richardson even suggests that Black witnessing is a type of protest journalism which has been centuries in the making. She writes:

“…I argue that black witnessing memorializes the more than 10 million Africans who were sold into bondage across the Atlantic Ocean for nearly 300 years. Black witnessing memorializes the 5,000 African American men, women, and children who continued to be victims of lynching across the United States between 1865 and 1965 — nearly a full century after the law said they were free. Black witnessing memorializes more than 1 million African American and Latinx men and women who have fallen victim to mass incarceration since the late 1970s, when racism learned to disguise itself as a ‘War on Drugs.’ Black witnessing memorializes the men, women, and children who have been shot and killed by the very people who are charged with protecting them. In short, black witnessing provides proof of the many eras of anti-black racism, in all of its perverse mutations.”

Malcolm X, James Baldwin, and Marion Stokes each fulfilled the important role of witness. Each intuitively harnessed the power of media to tell their story and provide guidance for future generations. Now, following in their footsteps, entire generations are using new media to collectively carry on those legacies of Black witnessing.

“Black witnessing reclaims black lives and stories from the margins,” Richardson writes. “Black witnessing corrects false narratives. Black witnessing gives us new data points around which we can theorize more intersectional ideas of how journalism works. Black witnessing is about seeing and being seen, about being valued and believed.”

Despite a country and world where every great step towards emancipation seems to be met with an equal hostility, Black witnessing has already carried us great distances.

The question is: now that we’re here, just where will we be taken next?

Ω