A n imposing wall of rotary dials, turreted by oscilloscopes, draped in spaghettied cables, emitting a series of creaks, groans, and unearthly bubbles, is one of the most iconic images of electronic music. These monolithic machines — known as modular synthesizers — have had an enormous impact on how we visualize and hear The Future.

n imposing wall of rotary dials, turreted by oscilloscopes, draped in spaghettied cables, emitting a series of creaks, groans, and unearthly bubbles, is one of the most iconic images of electronic music. These monolithic machines — known as modular synthesizers — have had an enormous impact on how we visualize and hear The Future.

Despite the intense amounts of innovation, fabulous engineering, and sonic control to a nearly molecular level, these musical marvels were nearly extinct at the turn of the century, due to the digitization of nearly everything.

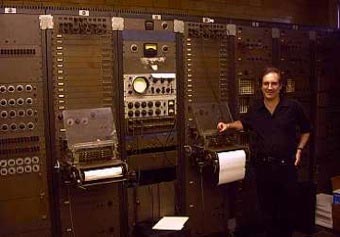

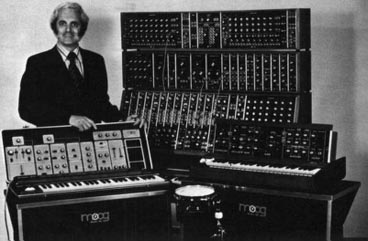

Once owned exclusively by enormous universities, such as the RCA Mark II at Columbia-Princeton University’s Computer Music Center, early modular synthesizers were exorbitantly expensive and the size of small warehouses. This began to change with the emergence of two legendary names in early electronic music — Robert Moog (pronounced with a long O) and Don Buchla — who began manufacturing commercial synths in the early ‘60s. These two innovators would define a schism that haunts electronic music to this day.

Moog’s synths, the most famous and iconic electronic instruments of all time, achieved widespread popularity thanks to Moog’s decision to attach the familiar black-and-white keyboard instrument everyone knows. Musicians could work the Moogs like futuristic organ wizards, playing intricate baroque counterpoint with one hand while performing the signature filter sweeps with the other.

Moog’s synths, the most famous and iconic electronic instruments of all time, achieved widespread popularity thanks to Moog’s decision to attach the familiar black-and-white keyboard instrument everyone knows. Musicians could work the Moogs like futuristic organ wizards, playing intricate baroque counterpoint with one hand while performing the signature filter sweeps with the other.

Buchla, however, didn’t want to restrict the endless possibilities of electronic music. Instead of a keyboard, which would inspire musicians to make music like they always had — thus relegating the new synths to wacky gimmicks — Buchla opted for a touch sensitive controller, which produced eerie theremin-like warbles. Buchla’s synths, characteristic of the West Coast scene, produced sounds unlike anything anyone had ever heard before: wild, glistening, horseshoe nebulas and alien swamplands.

The schism can be seen today in the dichotomy of high-gloss pop with electronic flourishes that create hyper-efficient big room club bangers, versus the alien beat deconstructions of recent labels at the vanguard of dance music, such as Diagonal or PAN.

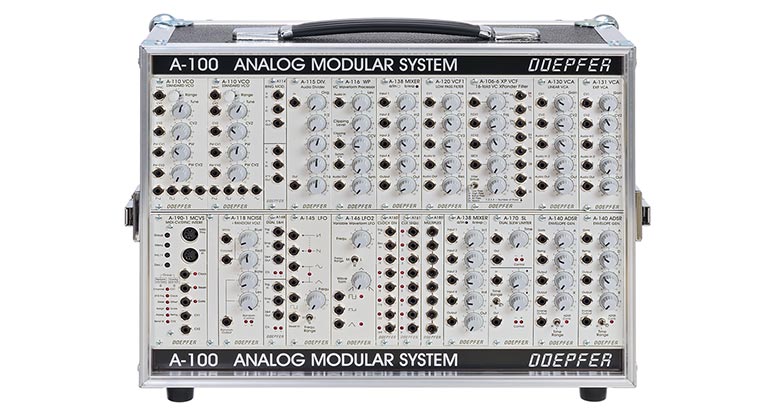

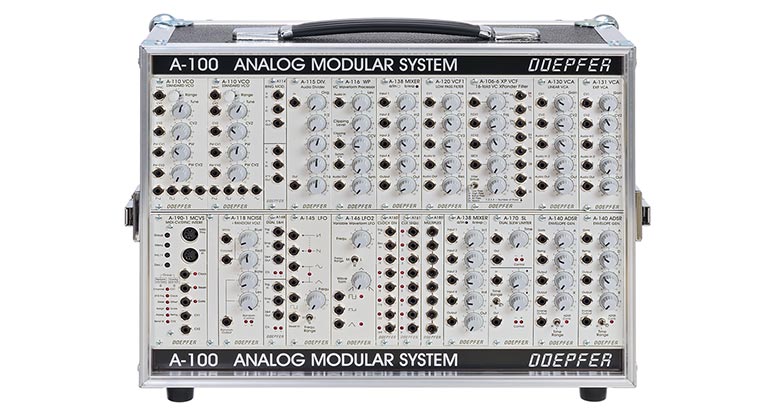

In the 21st Century, modular synths have been enjoying a Renaissance, thanks, in large part, to a new manufacturer, Doepfer’s Eurorack. The Eurorack format is smaller and more affordable than the archaic versions, inspiring a new generation of basement New Age head-nodders to get lost in sequenced mantras and oscillator meditation.

As technology has become more amorphous, surrounding every aspect of our daily lives, musicians and producers are returning to the intuitive, tactile modes of production encouraged by modular synths. New modular components are constantly striving to pack more features into more efficient packages, serving as a sonic analog to today’s design and development culture. Modular synths also provide a much needed sense of community to their acolytes, with swap meets popping up in cities around the globe, for devotees to gather and geek out.

Recordings of modular synth run the gamut from sterile, academic laboratory studies to full-on alien landscapes. Sometimes they are the sound of a lone meditator, lost at the patch bay and laid straight to tape. At other times, the bubbles, burbles, whooshes, and laser zaps are recorded and layered into intricate tapestries of electronic exotica.

In 2013, the documentary I Dream Of Wires told the story of modular electronics, from the Electronic Sackbut to the Eurorack, in a mind-melting 4-hour “hardcore edition”. I Dream Of Wires has recently been re-released as a theatrical cut, which is now streaming for the whole world to see. To honor the occasion, we’ve compiled 25 essential modular synth records — listed in no particular – which examine the wide range of tones, textures, and styles these archaic electronics are capable of.

Martin Gore – MG

Martin Gore’s main musical project, Depeche Mode, have been pushing the limits of what synths are capable of since the early ’80s. While Vince Clarke may be the best known synthesist in DM, Martin Gore has recently issued one of the best modular synth records ever laid to tape, with this year’s MG. (Editor’s note: read our album review here)

MG was created using Doepfer modules, such as the Trigger Riot and the Noise Engineering drum module, which were then spun into quicksilver blasts of highest-quality, high-brow club music. The fidelity is staggering, pummeling your diaphragm in the most delicious way imaginable, while disembodied samurais speak prophecy and the stars shine in blacklight.

It’s the perfect combination of the laboratory and the dancefloor, hinting at the way forward for not just modular synthesis, but all electronic music. Plus, it’s a testament to modular synths’ inspiring nature that Martin Gore can make music this fresh and exciting, three decades into his career!

Emerald Web – The Stargate Tapes

Synthesizers of all kinds have long been embraced by futuristic New Age hippies. It makes sense; the self-perpetuating sequences and tonal minutiae lend themselves to staying present in the moment, clearing the mind, inviting you to explore the texture.

Emerald Web were Bob Stohl and Kat Epple, who began playing their electronic meditations at planetariums and laser light shows. The duo would layer drifting flute music, bells, and chimes with the pulsing circuitry of a wide battalion of modular synths.

It’s a testament to modular synthesizers, and Emerald Web, that this record is even listenable, let alone a meditative masterpiece. If you’ve ever felt angry and betrayed at those New Age music listening kiosks, at the bland bloated aural wallpaper that ’80s New Age synth records would succumb to, Emerald Web will re-instill your faith.

Aphex Twin – Syro (Classics, Varied)

For his first album in years, Richard D. James, Aphex Twin, used nearly every electronic music-making device known to humankind. Unsurprisingly, some modular synths are on the list. Syro could be seen as the ultimate hybrid electronic record, with James using gear from every era and weaving them into compelling dancefloor narratives that are both academic and funky. In conjunction with Syro‘s bizarre press cycle, Richard D. James dumped metric tons of unreleased recordings onto an anonymous SoundCloud account, resulting in the companion compendium, Modular Trax. Both should be investigated as an entryway to modular synths.

Keith Fullerton Whitman – Multiples (Serge)

At the time of its release, Stereo Music For Serge Modular Prototype was included on the label Sub Rosa’s legendary archival series, An Anthology Of Noise & Electronic Music Vol. 3, sandwiched between serious academic composers Hugh Le Caine — creator of the first modular synth, the Electric Sackbut — and Turkish composer İlhan Mimaroğlu. Whitman’s inclusion is notable as he’s coming from the underground, having started out as a drum ‘n bass producer under the name Hrvatski in the late ’90s. Whitman has been one of the most active and vocal proponents of the modular revitilization, with dozens of records exploring various modular synth models.

Multiples was recorded at Harvard University’s Studio for Electro-Acoustic Composition during a teaching residency. It’s a fantastic example of the wide range of sonics these machines are capable of, especially when wielded and welded together by Whitman into compelling sonic vistas, which bridge the gap between academia and New Age meditation cassettes. This is the sound of the triumph of the underground: Harvard goes electropunk!

Raymond Scott – Manhattan Research, Inc. (Early Electronics)

Although most of Raymond Scott’s notoriety comes from his music being adopted by Warner Bros. to score the adventures of certain animated pigs, ducks, and rabbits, Raymond Scott was a pioneer of early electronic music first. Scott developed a very early synthesizer, the Electronium, in 1949, along with numerous other SF inventions.

Manhattan Research, Inc., a double album released by a Dutch label in 2000, is a grand overview of Scott’s career. Scott’s bubbles, burbles, zaps, dings, and squelches were used heavily on television and commercials during the ’50s, becoming a kind of folk memory of what the future should sound like. If you miss the days when Scrubbing Bubbles seemed high-tech or just want to kill some time waiting for your flying car or jetpack, Manhattan Research Inc. is an essential document for anyone interested in electronic music history.

Dick Hyman – Moog (Moog Modular)

Moog is an example of the schmaltzy novelty hi-fi test records that modular synth records were pigeonholed into becoming, yet is nonetheless a source of some way out sounds. Laser zaps and underwater harps meet rinky-dink “Popcorn” melodies, which are then soldered on to easy-swinging lite jazz, with catchy track titles like “Topless Dancers Of Corfu” and “Tap Dance In The Memory Banks”. “The Legend Of Johnny Pot” sounds like The Turtles’ “So Happy Together” on Saturn while “Four Duets In Odd Meters” sounds like epic proto-grime performed on a TI-80.

Ataraxia – The Unexplained

Prolific synth composer Mort Garson truly delivers on the spooky speculative sonics of sci-fi electronics. Eerie warbling theremin-like oscillators meet ominous doomy bass synth, sounding like a classic electric horrorscore, but predating John Carpenter’s Halloween theme by three years. This is truly a dusty lost forgotten blood-soaked gem of astral travel modular synth, for your next seance or dance with the goat in the woods.

Morton Subotnick – Silver Apples of the Moon

Silver Apples of the Moon may be one of the most iconic electronic records of all time, commissioned by Nonesuch Records to portray the sonic potential of the newly emerging electronic instruments. What could’ve been a glorified hi-fi records is instead a masterpiece of irregular tones and glistening, pulsing textures unlike anything anyone had heard before.

Silver Apples of the Moon is the proto-typical academic synth sci-fi record, the kind you’d find in some thrift store adorned in Expo 70 font. Thanks to the Buchla synth, of which Morton Subotnick was a passionate admirer, Subotnick’s music is freed from the constraints of meter, harmony, tonality. Instead, this is the sound of wind through wires, the sound of motherboards talking to themselves, as daisy-chained tea kettles stretch off to Primal Scream’s Vanishing Point.

Pauline Oliveros – Alien Bog/Beautiful Soop

Alien Bog is a beautiful, otherworldly record created with the experimental Buchla machine. Pauline Oliveros is best known for developing the concept of “Deep Listening” and “The Third Ear”, so it’s not surprising she would gravitate towards the in-depth control of a modular synth. What is surprising is how interesting Oliveros’ compositions are — playful, imaginative, harsh, scary, and soothing. Oliveros takes the imaginative sci-fi possibilities inherent in these tuned oscillators to new heights, creating dense and tangled sound worlds in the process. Alien Bog is a surefire intergalactic voyage.

Hugh Le Caine – Compositions Demonstrations

Although not all of the recordings that make up Compositions Demonstrations were recorded using modular synthesizers, the documentation of the first ever voltage-controlled synthesizer, the Electronic Sackbut, makes this collection noteworthy.

Canadian scientist and composer Hugh Le Caine invented the Electronic Sackbut after a youth spent dreaming about beautiful sounds that could be achieved using electronics. Le Caine worked for the National Research Council of Canada, helping them in the development of two early electronic studios at The University of Toronto and at McGill University in Montreal. Le Caine separated the Electronic Sackbut into components, with every element meant to feed into and control the other modules. Le Caine’s entire studios were modular synths, and he dreamt of a future where anybody could make interesting and impressive sounds without having to be proficient at playing an instrument. His designs, which always focused on expressiveness and playability, would have a direct influence on the Moog Modular, arguably the most famous and recognizable electronic instrument of all time. Hugh Le Caine is truly a godfather and hero of early electronic music.

Ned Lagin – Seastones w/ Phil Lesh, Jerry Garcia & David Crosby

Ned Lagin’s electroacoustic masterpiece Seastones, released in 1975, may be one of the most ambitious hybridizations of classical music and theory and emerging technology ever laid to tape. Over the course of five years, Lagin used every tool and technique available to electronic musicians at that time, including incorporating early computers with nearly every modular synth available.

The inspiration for Seastones was not some dry academic theory, but the natural world around us. Lagin was moved by the uniqueness of rocks washed up by the sea.

Instead of an intellectual exercise, Lagin uses the literal physicality of the modular synths to create this feeling on interconnectedness. Upon its release, Seastones was called “electronic cybernetic biomusic,” and this is apt. This is the sound of underwater life, as channeled through chirping circuitry and deep sea sonar transmissions. This is the sound that crustaceans may make, while singing to themselves.

Seastones is also noteworthy for several celebrity appearances – The Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh and notorious ’70s snowbird David Crosby. There is not a jam band in sight on Seastones biomechanoid soundscapes, however, so don’t worry!

Seastones is truly a step towards a transhuman music that speaks to the natural world without us in it.

Benge – Twenty Systems

Being alive in 2015, we have the benefit of hindsight, rather than observing technological advances as they occur. It’s like binge-watching the past, creating a rush, a sensation of momentum, forming new connections and illustrated overlooked currents.

Twenty Systems, from the English producer Ben Edwards — who makes music under the alias Benge — is a Time Machine-like guided tour through the history of modular synths. Each track on Twenty Systems was created using a different modular system, from Moog to EMS to more recent creations like the early digital synthesizer the Fairlight, as well as obscurities like the PPG Wave. Each track, for the most part, was recorded live and straight to tape, taking you on a fly-on-the-wall tour of Benge’s subterranean London studio.

Twenty Systems is like a modular synth greatest hits, spanning nearly 20 years in an hour. If you were ever curious or looking for a place to hear specific examples of particular synthesizers, Twenty Systems is your chance.

Untold – Echo in the Valley

Echo in the Valley updates modular synth sounds for the 21st Century. It’s a classic speculative headtrip, with imaginative titles like “The Miller”, “The Maze”, “The Pageant”, and “The Gargoyle”. Such references suggest some kind of pagan woodland mystery, like some dark imaginative fairy tale, which is an interesting angle on the aleatoric beeps, bleeps, stuttering static and white noise peat moss of Echo in the Valley.

EITV would be noteworthy for this fact alone, but Jack Dunning does us one better. The British producer released Echo in the Valley on a limited edition, hand-tooled USB key shaped like a log, but otherwise gave the music away for free.

Untold’s take on modular synthesis is a simulacrum of why these machines are relevant in the immediate satisfaction world of 2015. Physical artifacts give us something to hang on to, a reason to care, while the music encoded therein swirls around us in the ether.

With Echo in the Valley, Untold’s bringing electronic music back to the Earth, making it something that is relatable to all, and creating manifold fantastical daydreams in the process.

Sam Prekop – The Republic

The Republic, a recent album on legendary indie psych-out label Thrill Jockey, succeeds in being both intellectual and emotional, adventurous yet melodic. This tunefulness may come from Sam Prekop’s background in the influential indie rock band The Sea And Cake, where Prekop pens sensitive yet tasteful jazz rock for modern day bachelor pads.

There is nothing “easy listening” about The Republic, although it is easy on the ears. Prekop wires his sequencers and oscillators into self-perpetuating pirouettes of sound that take the listener on a journey. If you find fascination in a sonic approximation of the rusty-monochrome of Tarkovsky’s Stalker bursting into the glorious Technicolor of The Zone, The Republic is for you.

Brian Eno – Music For Airports (ARP 2600)

While modular synthesis was only one technique out of many employed on Brian Eno’s masterpiece, Music For Airports, it is worthy for inclusion as one of the most iconic electronic albums of all time.

“2/2”, the last track on Music For Airports, was created with an ARP 2600. The Arp’s irregularly shifting sequences creates a sort of light organ for shifting shadows, as musical figures coalesce and dissolve. Music For Airports was an early attempt at “generative music”, self-perpetuating ambient music machines, creating evolving sonic worlds in perpetuity. With Music For Airports, modular synthesis gets organic and emotional, like the first human being stepping on the shores of some alien world for the first time. Music For Airports is also the first record marketed under the term ‘Ambient’, kickstarting the introverted psychonaut chill-out revolution.

Laurie Spiegel – Obsolete Systems

Most electronic musicians emulate the sounds of outer space. Laurie Spiegel’s music has actually been to outer space. Spiegel was chosen to compose the lead track on the infamous Voyager Golden Record, intended as a communication with extraterrestrial life about who we are as human beings. Laurie Spiegel chose a computerized version of Johannes Kepler’s 1619 treatise, “Harmony Of The Worlds.”

Spiegel’s extraterrestrial music is collected elsewhere, on the equally excellent The Expanding Universe, but Obsolete Systems features more of the composer/programmer’s modular works. The luxuriant drones and alien telegraphs were coaxed from a variety of archaic electronics, including the Buchla, Apple II computer, the McLeyvier computer-controlled synthesizer, and the GROOVE Hybrid System. Obsolete Systems was recorded between 1970 and 1983, but sounds frighteningly contemporary – a prototype for the emerging cosmic meditative underground.

This is the sound of a lifelong love affair with technology that is both avant-garde yet all-too-human.

Suzanne Ciani – Lixivations

Suzanne Ciani has been hugely influential in bringing the futuristic sounds of modular synths to the masses. Suzanne Ciani is best known for a series of logotones and video game sound design throughout the ’80s, working for huge companies like Atari, Coca-Cola, and Discover Magazine.

Although Ciani’s music has more of the glassy digital sheen associated with ’80s synthesis, Ciani got her start working with modulars. After graduated with an MA in composition, the electronic composer was introduced to visionary West Coast synth designer Don Buchla, who would have a formative influence on Ciani for decades.

Buchla showed Ciani the possibilities of making music outside of the piano keyboard. Ciani would eventually take the expressive potential of the Buchla’s glistening glissando to its peak. She plays Buchla’s wavering arpeggiators like a first chair violin virtuoso. The expressiveness and imagination of Ciani’s recordings would help introduce the public to the idea of New Age synthesis, which erupted during the ’80s.

Charles Cohen – Brother I Prove You Wrong

Brother I Prove You Wrong reminds us how much we love the hands-on-knobs approach of modular synth. Charles Cohen’s oscillators twitter like birds and groan like blue whales, conjured from the rudimentary instrument, the Buchla Music Easel.

The Buchla doesn’t have a piano keyboard, instead featuring a touch-sensitive controller. This makes sliding, bell-like theremin warbles possible, resulting in more etheric shapes than blocky western tonality. Brother I Prove You Wrong is no academic special FX record, however, as Cohen also yokes the Easel to repetitive hypnotic Berlin School sequencer grooves, on stripped down proto-techno like “Sacred Mountain”. Brother I Prove You Wrong will leave you seeing telegraphs and mechanical birds, from a Philly musician nearly 70-years-old.

Donnacha Costello – Love From Dust

Irish producer Donnacha Costello is a master of limitations. His most famous output, the Colorseries, utilized a stripped-down electronic palette, using only a few pieces of analog kit to produce streamlined minimal techno bangers to approximate the sound of RGB.

Love From Dust is Donnacha Costello’s first album since 2010, which speaks to the inspiring and motivational nature of these instruments. But instead of making tracks for dancefloor abandon and hedonistic explosion, Love From Dust is introspective, emotive, and contemplative. Warm sine waves ebb and pulse like amber gently lapping up against your ankles, as tones converge and dissolve like colored shadows.

Factory Floor – Factory Floor

Factory Floor’s arc-welding of modular synthesizers (along with other classic analogue hardware) and steely post-punk precision, alone, would make the London three-piece worthy of inclusion on this list. Their stellar self-titled record from 2013 is a tight, edgy, coiled spring of an album, as perfectly constructed as finely machined polished chrome, and it shows that Factory Floor don’t need any novelty to be noteworthy.

Punk rock was always about breaking boundaries, of dreaming of a future that included everyone. For all of its futurism, it was always sort of ironic that the first wave of punk rock was basically Chuck Berry and Rolling Stones riffed played double-time, high on sniffin’ glue. Post-punk, following quickly in punk’s Doc Marten footprints, was more future-oriented and inclusive, incorporating non-Western musics from all over the globe and the emerging technological music, like hip-hop and krautrock.

Finally, 35 years after the revolution, Factory Floor are bringing the incendiary potential of precision and energy that post-punk could’ve been. But instead of shivering in dystopian fear, FF are dancing within the machines. This is the sound of clockwork disco, of fleeing cybernetic assassins past chain link and over freeway overpasses. For all of the punks who also rave, this is for your next back alley dance party.

Tangerine Dream – Zeit

Another staple of The Berlin School, Zeit, is a sprawling double-LP sailing on the solar winds of Alpha Centauri. It is Tangerine Dream at their most introspective and elegiac, is a confluence of progressive German synthesists, as the classic line-up of Edgar Froese, Christoph Franke, and Peter Baumann — then still in his teens — were joined by Florian Fricke of Popol Vuh.

Fricke’s meditative mysticism seems to have rubbed off on Tangerine Dream, as mournful contemplative organs and gentle waves of sound create a timeless feeling of ceremony. The visitors actually come when you visit the stone circles this time, however, as EMS VCS3 and a large Moog Modular, are employed to give the anti-gravity sensation of deep space.

Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith – Euclid

Euclid, released at the beginning of this year, is both traditional and entirely futuristic. Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith began with a love of African mbira music, employing a Buchla Music Easel to create the loping, bouncing, twirling African rhythms. At times sounding like Chinese music, other times like a safari across the Savannah, Aurelia Smith is using electronic music to trace the connecting threads between human music from all over the globe. Modular synths, after all, are all about connections.

Euclid also benefits from modern production standards and exquisite multi-tracking, with Aurelia Smith layering the buzzing bubbles and whooshing whippoorwills into glistening acid lines and future pop ululations. Euclid may be the most fun record of this collection — all the better to turn your commuting and grocery shopping into extraterrestrial adventures.

Alessandro Cortini – Forse 1 – 3

Alessandro Cortini’s day job as Nine Inch Nails’ synthesist may have made him a household name, but Cortini’s been forging a name and identity for himself as a modular fetishist for years.

The Forse trilogy was recorded using a Buchla Music Easel, as with Charles Cohen, but Cortini channels mighty waves of drones and textures, using the limited palette of the Buchla to lap like waves on Europa. It’s also thrilling to hear the Buchla captured in glorious modern hi-fi. You can practically smell the circuitry sizzling, as Cortini’s gentle waves rap at your skull.

Cortini is someone who thrives on limitations and restraints, and luxuriates in the texture of sound. Forse 1 – 3 is the sound of listening to machines hum and purr, transforming your apartment into some tropical alien beach, sunbathing beneath four suns.

Klaus Schulze – Timewind

Klaus Schulze is an archetypal example of the style known as “The Berlin School”, comprised of technologically-driven, sequencer-obsessed futurists forming a kind of ambient shadow to the rhythmic propulsion of krautrock. While krautrock would have more of an impact on rock ‘n roll, The Berlin School’s live electronic jamming predicted raves, chill-out rooms, and ambient music. Timewind, one of the earliest albums from the insanely prolific Klaus Schulze, is a good cross-section of the techniques employed by the Berlin School, as Schulze hand-manipulates sequences from an ARP 2600 and EMS Synthi.

All of the titles on Timewind are references to the composer Richard Wagner. Schulze’s instantaneous, endless compositions could be seen as the ultimate update of the German classical ideal, as skeletal chords dance and chase one another eternally.

Jessica Rylan – Interior Design

Another sonic alchemist that got their start working under Don Buchla, Jessica Rylan is noteworthy for actually building her own synths. Interior Design was was her first fully-formed synth record, released on the experimental juggernaut Important Records.

Rylan’s modular synths cross the void from ’50s academic synthesis to the noise underground of the ’00s. Raw, scraping, throbbing, burbling, wheezing, hissing… Rylan’s long-form compositions are uncompromising yet sonically interesting. Rylan updates the sterling chrome sound palette of early synth records into pastel curlicues of 8-bit abstraction, sending one lost into a ketamine daze in Lavender Town.

In 2013, Jessica Rylan started her own modular synth company, Flower Electronics, combining her love and deep knowledge of modular synthesizers into colorful and imaginative designs to kick-start creativity and invite sonic exploration. It is the efforts of underground aficionados, like Rylan, that have kept these monoliths alive for a new generation to explore and innovate.

Ω

[…] sounds, and the nifty patches let producers program any combination they could imagine. Buchla opted for a touch sensitive controller instead of a keyboard because he wanted to inspire musicians to create music in a new […]

Who is BRAIN Eno?

Wonderful list – thanks for the great recommendations!

Eliane Radigue’s ground breaking work on the ARP 2500 deserves a mention 🙂

Thanks for your suggestion!

What, no Air!? 10,000hz Legend is…. Legend