The ‘Biospherians’ pose for the camera during the final construction phase of the Biosphere 2 project in 1990. Left to right are: Mark Nelson, Linda Leigh, Taber MacCallum, Abigail Alling, Mark Van Thillo, Sally Silverstone, Roy Walford and Jayne Poynter. The 3.1 acre air- and water-tight building became their home for two years. Biosphere 2 was designed to allow study of human survival in a sealed ecosystem. The costs of this controversial, $150 million project were met from private funds. The Biosphere 2 project building is at Oracle, Arizona.

To tell the biospherians’ story, Wolf had to travel to the past — to an archive housed in a temperature-controlled closet at the Synergia Ranch in New Mexico. There, he discovered what he calls the “fascinating pre-history” of the collective led by the charismatic John Allen, who would eventually direct the Biosphere 2 project. The first forty or so minutes of Spaceship Earth are composed from the six hundred hours of footage that Wolf discovered.

“It’s a lot of footage but not unmanageable with a strong group of collaborators. I worked with a team of story producers, associate editor, and editor David Teague, and we all mined the material looking for things that didn’t just literally illustrate the story, but things that were cinematic or that had a kind of metaphor in them to help tell the story,” details Wolf. “Something like a shot in the film of the synergists running up a staircase that goes to nowhere, on a ruin in South America.”

During this part of the film, which feels almost like a nostalgic memory, we learn about this eccentric community-slash-family and its mind-bending projects. Grainy footage shows the synergists contorting their bodies during experimental theater exercises, reading books like Naked Lunch and Silent Spring, and toiling on the ranch. But while the synergists were profoundly of their time, they also “defied the clichés of hippies,” says Wolf. They shunned drugs, studied the natural sciences, and, most surprisingly, were unabashed capitalists.

To quote one of the synergists, “We weren’t a commune; we were a corporation.” Their search for revenue, as well as the cutting edge, took them from London, where they started an art gallery, to Kathmandu, where they built a hotel. Ironically, these environmentalists found the funding for their projects in the deep pockets of businessman and philanthropist Ed Bass, a rogue member of the Texas oil dynasty.

“They were very interested in producing enterprises that weren’t just ecologically sustainable, but also economically sustainable,” explains Wolf.

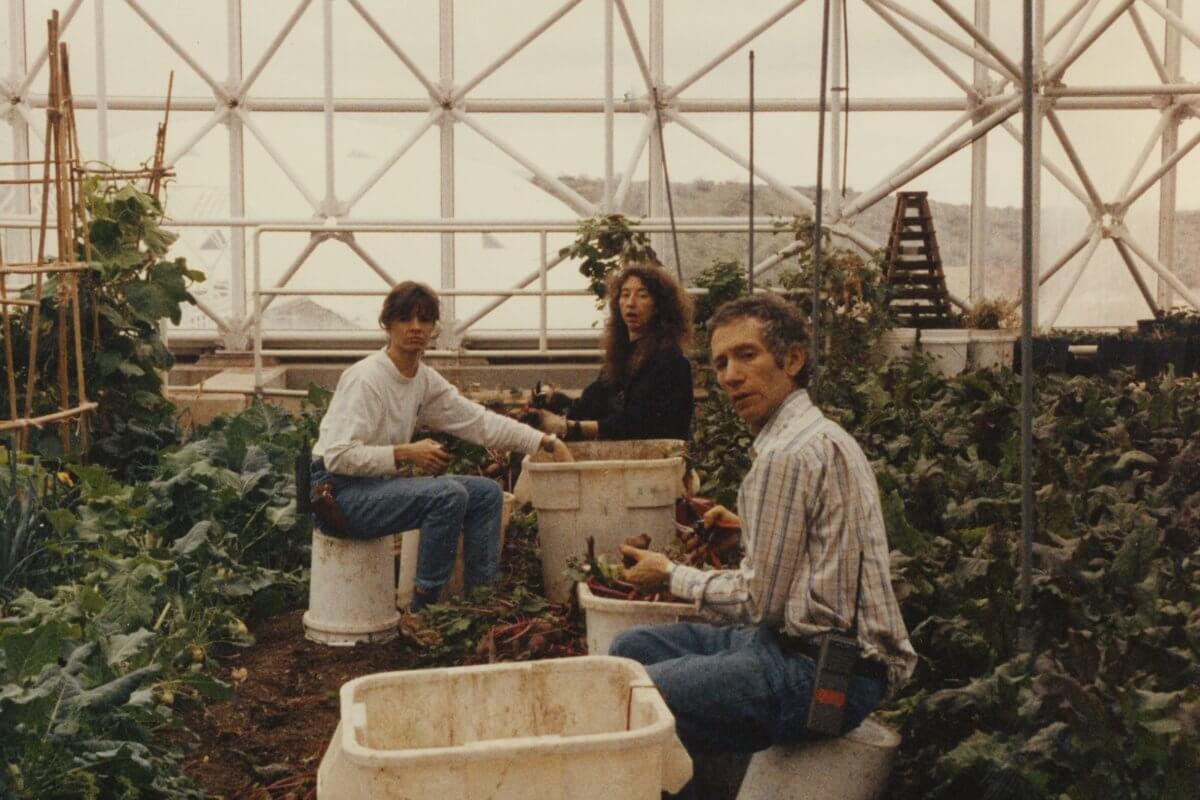

Biospherians harvesting produce. Photo courtesy of NEON.

Perhaps no moment better encapsulates the synergists’ wild ambition than the scene of them building a massive ship. Called the Heraclitus, the ship boasted multiple levels and proudly flew the flag of Panama and had all the grandeur of its namesake — an ancient Greek philosopher known for his mysticism. Yet when the formidable vessel rushes into the San Francisco Bay, it looks for a moment like it might tip over — and then, like a miracle, it steadies itself. Crew members dance in the sunshine, and the score, composed by Canadian composer Owen Pallett, is soaring and triumphant. For Wolf, this scene was crucial in establishing the capability of the synergists.

“It really came to symbolize the spirit of this group — the idea that a small group of people can coalesce their skills to do something unimaginable when they’re not experts,” he says. “It’s not just about technical skills or expertise, but also about a sense of adventure.”

The Biosphere 2 project was an extension of their ambition — not just the most exciting thing they had ever done, but also the most forward-thinking. Inspired by sci-fi movies like Silent Running where ecological destruction has made Earth uninhabitable, Biosphere 2 was meant to be a prototype of an extraterrestrial colony. The colorful early designs for the dome are part architecture blueprint and part artwork; half plan and half prophecy. Biosphere 2 could take the good from the Earth, which they termed “Biosphere 1” — such as its coral reefs and sustainable agriculture practices, while leaving out the bad, such as its pollution and crookedness. According to one participant, the chipper Sally Silverstone, it was about “locking everyone else out” to retreat to the protective cocoon of the biosphere.

Instead, the problems of Biosphere 1 crept back in — or maybe, according to Wolf, were baked into the project from the beginning.

“It’s important to think about reimagining a world, but also to understand that the dynamics of society that already exist will inevitably replicate themselves in a modeled society,” he says.

Here on Biosphere 1, carbon dioxide accumulated rapidly in the atmosphere during the ‘80s and ‘90s owing to the greenhouse gas effect. The same problem occurred on Biosphere 2, where carbon dioxide levels rose as oxygen levels fell. The biospherians were constantly out of breath, yet still had to spend hours a day farming crops that often failed. The “mad scientist” Dr. Roy Walford, who believed that calorie restriction was the secret to longevity, didn’t help matters by encouraging his fellow biospherians to starve themselves for the sake of his experiment. His utopian dream of living to 120 years had a dark side; one biospherian, the good-natured Mark Nelson, calculated that if he kept losing weight at the same rate, he’d emerge out of the biosphere at minus ninety pounds. Luckily his prophecy was not fulfilled, but the biospherians nevertheless looked gaunt and hardened after their two-year experiment.

The project’s challenges and easy-to-mock aesthetics, of retro-futurist suits and a Xanadu-esque honeycombed dome, contributed to the media’s skepticism. While news coverage had initially been glowing and almost as hyperbolic as the biospherians themselves — one TV station called them the “darlings of the new age” — it soon soured.

“I think the perception from the media was that this is a project in which nothing comes in and nothing comes out, and that is in essence the whole game, whereas the biospherians and the synergists didn’t see that being the point of their project,” says Wolf. “Their point was, can a closed system work? And can we continue to develop this system for a hundred years and to one day support human occupants in an extraterrestrial setting? So, they were dreaming big, [but] I think the media distilled all of that ambition into a more simple and basic premise.”

It’s also debatable whether the Biosphere 2 project was scientific at all or rather, as one detractor put it, “trendy ecological tourism.” Was it grand or simply grandiose? An example of astonishing vision or astonishing hubris?

A rainforest ecosystem within Biosphere 2. Photo courtesy of NEON.

Undoubtedly, the project warped so much from its original intent that it became hard to evaluate. While the biospherians undertook sixty-four research projects related to the atmosphere, soil, coral reefs, and every other inch of Noah’s Ark 2.0, their data was destroyed or hidden away once Bass took over the project. He ousted Allen and replaced him with Wall Street bankers — including a young, shockingly environmentally-minded Steve Bannon — thus betraying the spirit of the project and proving that, as Wolf puts it, “idealism and capitalism are poor bedfellows.” In addition to being ridiculed as a failure of epic proportions, Biosphere 2 was not, in the end, profitable.

Spaceship Earth masterfully frames these debates without taking sides, and captures multiple perspectives without getting lost in the contradictions. For Wolf, it was crucial to understand the project’s subjectivity, because, as he describes, “There is no definitive story of Biosphere 2; it’s all from the personal points of view and interests of those who were involved . . . I want people who have the same story but contrasting perspectives on it, not only to give a multidimensional view of a story but also to simulate a kind of dialogue between all these different people.”

Thus, it was important to Wolf that Spaceship Earth, which is fundamentally about the power of small groups, have many narrators. A testimony from the desert ecologist who thought Allen had become paranoid is paired with that of the biospherian who passionately defended him. After they reached the two-year mark, one biospherian didn’t want to leave the dome, while another wished that Jane Goodall’s congratulatory speech were shorter so that she could escape sooner.

Ultimately, Biosphere 2 was a project both of its time and ahead of its time, emerging from the radicalism of the sixties as well as the techno-optimism of the nineties. Spaceship Earth perfectly captures this duality, and its retro-futurist aesthetics reinforce its heady ideas. The film also comes at the right moment: perhaps it is only with thirty years of hindsight that we can properly evaluate Biosphere 2’s lasting impact. While Spaceship Earth will inspire many dinner-table debates — were the biospherians mere eccentrics or forward-thinking geniuses? Crazy or just crazy enough? — Wolf hopes that his film can ultimately transcend those binaries.

“It should be an inspiring film about a unique model in which people actually achieve things, and get things done. Whether they were a success or a failure is beside the point, because they figured out how to do remarkable things,” he concludes.

With Spaceship Earth, Wolf, too, has produced a remarkable creation of his own.

Ω

The review, in addition to being well written, is intriguing and makes me want to see this documentary.

Interesting, well-written article about the movie of an experiment way ahead of its time. Isn’t something similar being done on a larger scale on the island of Lanai, Hawaii where there is an effort to make the whole island sustainable? Could the Biosphere project have been a seed project for Lanai? Or is it coincidental that Biosphere was located in Oracle, AZ and Lanai is owned by Larry Ellison, founder of Oracle? Either way, I’m looking forward to Spaceship Earth and encouraged that some people are enterprising enough to try to figure out what it may take to make our planet sustainable.

Biosphere 2 is now a tourist attraction in the Arizona desert. The staff and docents do their best to portray its current status as a laboratory for exotic and experimental plant life. In reality, it’s a sexed-up greenhouse. Pretty much a waste of a good day of vacation. Thank you for this well written critique!

What a fascinating, thorough and beautifully written article. My husband visited the biosphere and now I’m anxious to see the documentary.

When I watched the documentary, what struck me most was the difference between the effort to publicize Biosphere 2 vs their other projects, which were done outside the public eye and therefore on their own terms. Sometimes it’s good to have accountability on a project, because it can keep one honest (especially important if one wants the result to be scientific and meaningful), but it can also lead to immense frustration, as seen in the film. The Biospherians felt that the media did not properly portray their project, penalized them for “cheating” with the air purifier and the computer parts brought in, and ultimately destroyed what some felt was just another whimsical project. That’s the price you pay for media attention– it’s hard to control, and it can turn public opinion against you if there’s a more dramatic story to tell.