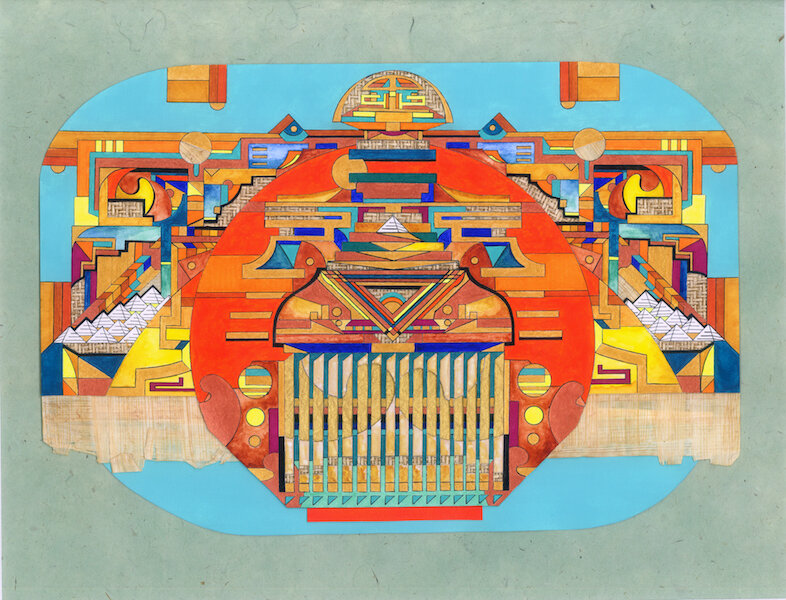

Black Starfleet is a meditation on black super(s)heros who use their superpowers to elevate the game. Drawn by hand, 70 hours, 14″ x 17″, paper, watercolor, acrylic, gold leaf paper, 2017. Sonic pairing: “Morale Chorale” by Frans Bak.

“I find that because of my background — as a Black person, as someone who has been very steeped in the legal field, and as someone who was a human rights investigator — I have a lot of secondary trauma that has come from the professionalizing of Black suffering, and a lot of personal trauma, just because I’m Black,” explains Z. “I’ve lived through a lot of my own trauma at the hands of the carceral system. And you know, my family has… There’s a lot of collective stuff that you just can’t escape if you’re from a Black family.”

“The drawing was what was saving my mental space. I think when you find something like that, you have to honor it and really pay attention to it,” says Z.

Z has honored the craft to this day. Though they describe their early pieces as “super basic,” their immediate Brooklyn community of artists and musicians was wildly supportive of their new hobby. Z began drawing obsessively. Every morning for two years, they would devote a minimum of two or three hours to the craft, and every night, an additional three or four more. They produced over 40 pieces during that period, which formed the backbone of their first art show in Brooklyn in 2017. Since then, their dedication has never wavered.

“I could do art twenty hours out of the day and forget what time it is. I have no concept of time when I’m doing this stuff. And to me, that is the definition of just being able to be free for a second,” they say. “And then, when you come out of it, you come back to all of the buffoonery that is this country.”

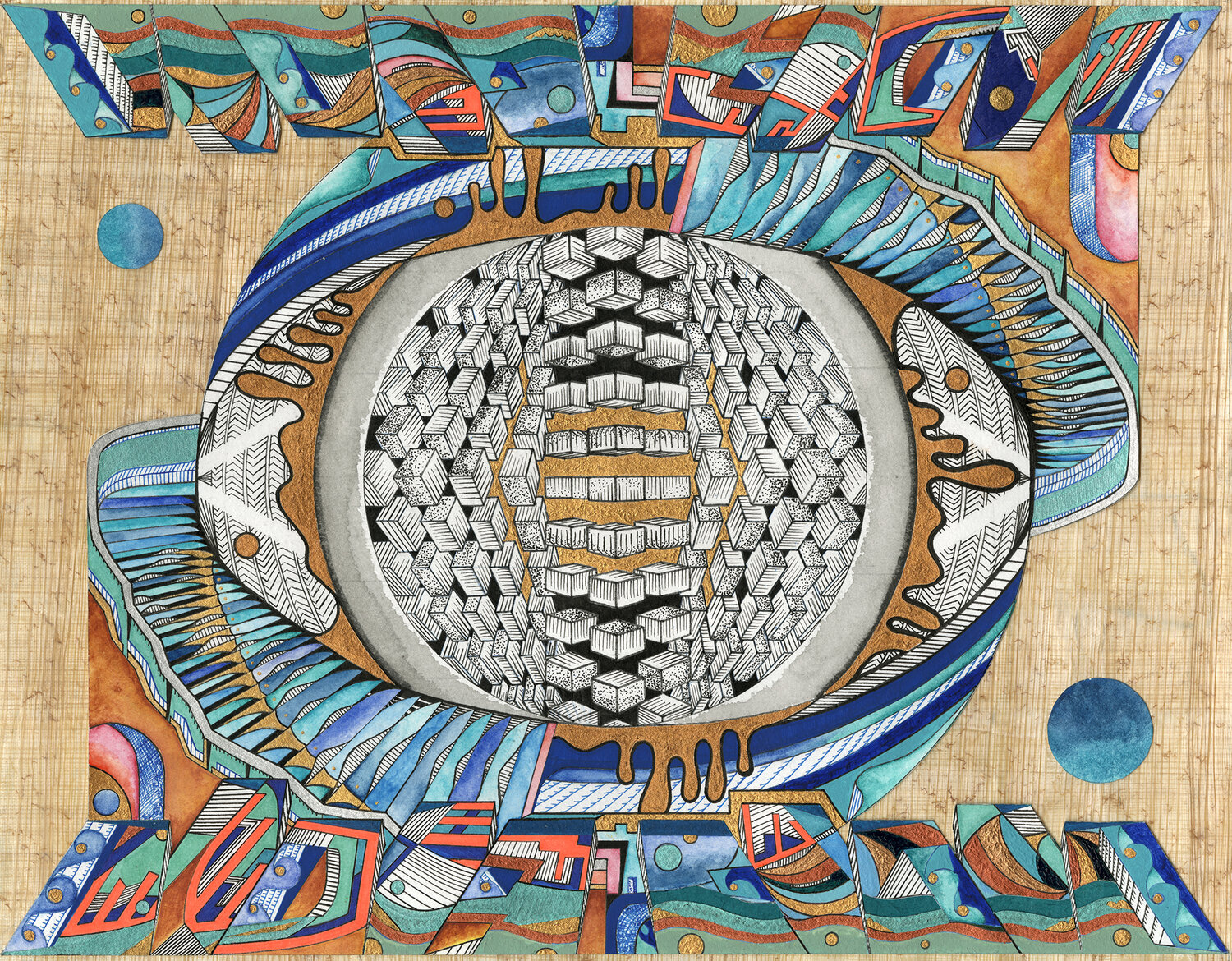

Sleeping Faces. Drawn by hand, 70 hours, 14″ x 17″, paper, sharpie, pen, gold calligraphy pen, 2016. Sonic pairing: “The Theory of Everything” by Johann Johannsson.

Transmuting Hate into Beauty

The youngest of four siblings from San Jose, California, Z now lives in Seattle. They come from a self-described lineage of “a powerful, southern black matriarchy that migrated from Oklahoma and Mississippi to California with nothing, and made something for generations to come.”

“My work is around Black people because I’m Black, and that’s just what it is…” says Z. “Obviously, not everybody’s experience is the same just because you’re Black, but I know a piece of what that suffering is, what that triumph is, and what that brilliance is.”

Z’s impressive ability to transmute that collective suffering into beautiful and intricate works of art is a true testament to the power of their intention and their ability to shift energy. Every piece since the moment they began drawing has become a healing meditation for Black people, focused on three elements: Love, Freedom, and Protection.

“We’re not safe anywhere in this country except [in] make-believe, and so, these are just collections of pieces that would be armor, or things that make us bulletproof, or things that make us untouched by systemic oppression,” they describe.

The energetic exchange between artwork which Z makes for protection and the traumatic assailants from which Black people need to be protected is complex. In their piece, Celestial Afropick, a glorious, colorful Afropick is presented as a symbol of “something that Black people could put in our hair that would then render the rest of our bodies bulletproof” — and is paired on Z’s website with the song “Wakanda,” as performed on the Black Panther soundtrack by Ludwig Göransson and Baaba Maal. Yet for the piece to reach its final form was a process; the Afropick only emerged midway through the creation of the piece, after Z learned of the murder of Stephon Clark in Sacramento, California. Just two hours north of Z’s hometown, Clark, 22, was shot in his grandmother’s backyard, while holding a cellphone.

“Because [each piece takes] me so long, there’s always somebody Black who’s been murdered by police. In every piece. Literally. For five years…” says Z. “Once those things happen, I write them on the back of that piece, and I really make an effort to send love and protection and encouragement, in my meditation, to that person’s family. I just want to make sure that I keep the family and that person in my heart, and I think these art pieces serve to make sure I don’t forget their names.”

Celestial Afropick. Drawn by hand, 85 hours, 11″ x 14″, paper, sharpie, papyrus, acrylic, 2018.

Baton Rouge, Louisiana’s Alton Sterling — along with more than twenty other Black people who were murdered by the police — are remembered in Pan African Flag, a hypnotic mosaic that features the rich colors and tones of flags on the African continent.

“The pressure and the pain of what people go through in the community affects everyone in the community, especially family members, says Z. “Erica Garner, Eric Garner’s daughter, was on the frontlines of talking about police brutality and being an activist, on top of her dad being murdered. She died of a heart attack. Those things are connected.”

Global events also influence Z’s artwork. Following the 2019 Christchurch Massacre, where two consecutive mass shootings happened at mosques in New Zealand, Z finished a piece entitled Christ Church Protector. Through it, they simultaneously sent blessings to the families of those victims and to Minneapolis Congresswoman Ilhan Omar — a Somali-American Muslim woman who was elected to office shortly just over half a year prior.

“We all know how much hatred [Ilhan Omar] gets for being an elected official wearing the hijab — literally just doing regular human things and being herself. So she needs that protection,” Z says. “I feel like the more people send positive and protective energy her way, maybe the safer she’ll be. We’ll never know, but to see and understand why all those people were murdered in New Zealand — literally for their faith — and to have a Klansmember like #45 in the White House spreading that hate around…”

“I like to think that that piece will forever be sending love to the families of those folks who lost their lives in that massacre,” concludes Z.

Christ Church Protector. Drawn by hand, 80-85 hours, 7″ x 10″, paper, watercolor, acrylic, bamboo paper, golf leaf paper, 2019. Sonic pairing: “BIG LOVE” by The Black Eyed Peas.

Transcending Time through Meditative States

Meditation is not only a central element in how Z transmits energy to families of the deceased and warriors of the living, but is intimately connected to how they relate to their work.

“Meditation in the art realm, for me, has always meant the space where I can just let my mind be completely still and be free,” they explain. “I feel like meditation for me is more allowing myself to be a conduit for the art or a channel for it, and just letting it come through me.”

Mirroring that, one might look to the role music plays. The artform — a historic, cultural, and spiritual tool for creating atmosphere and mood — steers specific energies and facilitates trance states within Z’s dynamic creative process.

“Depending how complex it is, [each piece takes] between 60 and 120-plus hours, so I’m listening to everything from Arooj Aftab to Vic Mensa to Rajna Swaminathan to Celina Dion to Alexis Ffrench,” describes Z. “It runs the gamut — but a lot of times, I’ll listen to things on repeat for hours. One song for just hours and hours, on a loop.”

“Go Tell ‘Em” by Chicago-based rapper Vic Mensa is one track, for instance, that repeatedly shows up in Z’s artwork.

“It’s basically a song about killing people who so-called ‘owned’ enslaved people. It’s about taking back the plantation… because it’s over and over again that we see systems of oppression reborn with different names,” says Z. “Prisons are simply the newest form of the plantation.”

Whether the genre is ambient, hip-hop, pop, electronic, or so on, Z often listens to musicians they have a personal relationship with, because the connection fundamentally helps them understand the energy each artist imbues their music with.

The Door of No Return. Drawn by hand, 24 hours, 6″ x 8″,paper, sharpie, acrylic, gold calligraphy pen, 2016. Sonic pairing: “Solomon” by Hans Zimmer.

However distant the reality of slavery and plantations may seem from the minds of the average non-Black person living in America, they show up in African-American art time and time again, regardless of medium or era. At times, they can even emerge in architecture — a field of study notoriously devoid of persons of color, at least within the United States.

In 2016’s “The Door of No Return,” Z references a place in Ghana where many Africans were forcibly shipped off the continent, never to return. The piece was inspired in theme and design by the work of David Adjaye, lead designer at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in DC, and as Z describes on their website, “The three ships in the middle represent the stolen and altered lives of people kidnapped from Ghana, while simultaneously speaking to the value of the golden children who struggled and triumphed on the shores they were forced to live on.”

“Each ship represents a ship full of ethereal gold, essentially,” explains Z, “because as a people, that’s how I always want to represent us: as a people whose value is unquestionable and a people whose spirit defies all odds.”

Within each of Z’s pieces, one can find an unbelievably rich spectrum of thoughts, intentions, and moods, woven into a geometrically-dense and detail-heavy tapestry of color, stroke, and line. Whatever goes is “whatever calls,” and pieces take on lives of their own, subject to changing inputs and intuition as they go.

“I don’t really plan this stuff,” says Z, “because I feel like part of the meditation is just letting whatever flow to be what flows…. I just let it do what it’s going to do.”

Every finished work feels like a page of an illuminated manuscript, full of references and symbols to be decoded. Appropriately, Z also frequently mounts their work on bamboo or papyrus — the world’s first paper, first invented in Egypt — and this historical nod speaks to Z’s subtle ability to create work that spans continents, as well as transcends time and space.

Mural with Aramis O. Hamer, 2020.

With such a prolific output and fully-formed artistic practice, it seems hard to believe that only five years have passed since Z began to make art — but opportunities are picking up. In June 2020, they completed their first two mural pieces, joining the ranks of many Seattle artists who have been given their first opportunities to create large-scale works, as a direct result of COVID-19 business closures.

“I’ve wanted to be a muralist for three out of the five years that I’ve been drawing,” Z explains, “and now, it’s finally happening.”

The first mural — a 35mm film reel-inspired piece started outside of Northwest Film Forum in Capitol Hill — was completed after the death of George Floyd, and located on the same block that Seattle Police Department teargassed peaceful protesters who supported Black Lives Matter. The second was a collaboration with local artist Aramis O. Hamer. Painted outside of the Black-owned Andro Barber Shop in Pioneer Square, the mural features another celestial afropick, of sorts, paired with a space-age Nefertiti-esque figure.

And just like Z’s initial foray into drawing, these unexpected murals are also fundamentally life-altering, setting them on a trajectory that they have long hoped for. Near the end of 2020, they will have their first West Coast art show at Wa Na Wari, an innovative space that “creates space for Black ownership, possibility, and belonging through art, historic preservation, and connection.”

The timing is welcome, but it also cannot seem to come fast enough.

“This is all I want to do… but at the same time, I know the reality of coming from a family that has no real generational wealth, and I need to be able to take care of myself and my folks,” shares Z. “But as soon as I can just be self-made from art, I’m leaving everything else behind. That’s the goal. That’s the ultimate goal.”

Thus, in the same way that Z uses their art as an energetic support mechanism for the Love, Freedom, and Protection for Black people, perhaps this article can also serve as an energetic support mechanism to amplify Z’s absolutely attainable hopes and dreams for their artistic future, which are:

“I wish to see my artwork all over the world in the form of public art. Someday soon, the most prominent galleries will know my name and be eager to showcase my work. Someday, the blankets, textiles, and garments I make from my art will be sold as high-end limited edition pieces… with proceeds going to support the gifts, talents, and ingenuity of the Black community. Someday, my art and its limitless possibilities will create endless opportunities for me and my family.”

Let it be heard and ring true.

Ω

kororulesthesun.ink

Sabrina’s Water Sky is a “piece of peace is a meditation on the earth, the sky, and the sustainability of our world.” Drawn by hand, 140 hours, 11″ x 14″, paper, watercolor, acrylic, papyrus, 2019. Sonic pairing: “All These Seas” by Young Marco, ft. Aardvarck.